Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Water SA

On-line version ISSN 1816-7950Print version ISSN 0378-4738

Water SA vol.51 n.2 Pretoria Apr. 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/wsa/2025.v51.i2.4129

SHORT COMMUNICATION

Investigating antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles: characterization with SEM-EDX and ICP-OES

Yassin TH Mehdar

Department of Chemistry, Taibah University, PO Box 30002, Al-Madinah Al-Munawarah 14177, Saudi Arabia

ABSTRACT

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is currently the most widely used type of plastic. PET plastic benefits include that it is lightweight, safe, cheap, and recyclable. Drinking water is an important route for human exposure to contaminants. One method of exposure is through leaching of antimony (Sb) from polyethylene terephthalate PET plastic. Antimony is a toxic element which causes harmful symptoms such as respiratory irritation, dysphagia, vomiting and eye and mucous membrane irritation. Leaching of antimony from three commercially available PET plastics was investigated in this study. The potential leaching of Sb was observed under different pH values, temperatures, and storage times. In this study, elemental mapping using scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) were employed to determine the weight percentages of antimony (Sb) on the inner surfaces of the PET plastic. The results revealed the presence of Sb in PET material, with significantly higher concentrations in PET 3, measured at 0.844 μg/L. Temperature and pH were investigated as factors influencing Sb leaching over time. The concentrations of Sb in bottled water ranged from 0.02 to 2.14 μg/L at different temperatures (25, 40, 50, or 60°C) and from 0.02 to 1.9 μg/L at pH values (6.5, 7, or 7.5) over 200 days. The maximum Sb concentrations reaching 2.14 μg/L at 60°C after 200 days, exceeded the Japanese limit of 2.00 μg/L. These findings highlight the potential health risks associated with Sb leaching from PET bottles, particularly under elevated temperature and low pH conditions.

Keywords: polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles, bottled water, antimony, SEM-EDX migration, ICP-OES

INTRODUCTION

Drinking water consumption in PET bottles has been steadily growing in the past decade. The Saudi market for PET bottles is increasing, driven by the nature of Saudi Arabia, which lacks natural sources of water, along with the country's rapid growth. There are now no less than 20 local brands on the Saudi market, in addition to the imported brands in this field (North and Halden, 2013; Carneado et al., 2015; Sánchez-Martínez et al., 2013; GAS, 2016).

The issue of antimony (Sb) leaching from PET bottles into drinking water has gained significant attention due to its potential health implications. These may include gastrointestinal problems, such as nausea, dysphagia, vomiting, and diarrhoea. In severe cases, antimony can lead to neurological disorders, and even kidney damage. It is important to note that the severity of these symptoms can vary depending on the concentration of antimony in the water (Gabel, 1997; Bach et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2014; Aghaee et al., 2014).

In 2010, a study was published in which the leaching of many inorganic substances from PET and glass bottles was investigated. All of these released elements had comparable concentrations in both kinds of bottles, except for antimony, for which leaching from PET bottles was over 20 times higher than from glass bottles (Reimann et al., 2010; Shotyk et al., 2006). High concentrations of antimony in PET bottles are due to the use of antimony trioxide (Sb2O3) as an essential catalyst for the solid-phased poly-condensation stage to form PET. This catalyst reacts effectively without inducing undesirable colours and has a low tendency to catalyse side reactions (Duh, 2002; Shotyk and Krachler, 2007). The objective of this research was to investigate the presence of antimony and its leaching rate from three types of PET bottles, and to highlight the influencing effects of water conditions, including temperature, pH, and storage time. Two different characterization methods were utilized: elemental mapping obtained using scanning electron microscopy-energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) and inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) (Ohnemus et al., 2014; Westerhoff et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PET bottles and chemicals

Three different types of PET bottles (PET 1, PET 2, and PET 3), each for a different brand of drinking water, were supplied from the bottle manufacturer directly and used throughout the investigation. The volumes of the bottles were 0.33 L.

Instruments and analytical conditions

The concentration of Sb in the PET bottles was quantitatively analysed using ICP-OES (Thermo Scientific, ICAP 6000 Series). The instrument operated at a radio frequency power of 1.2 kW, an argon coolant gas flow rate of 18 L/min, and a gas pressure of 30 psi. The samples were acidified with HNO3 (Sigma-Aldrich) prior to ICP-OES measurements. All solutions were prepared using ultrapure water obtained from a Millipore Direct-Q system. PET bottles were immersed in a detergent solution for 24 h, then repeatedly flushed with tap water and rinsed with ultrapure water to remove the detergent. Cleaned PET bottles were dried at room temperature.

SEM-EDX characterization

A Piranha solution at a ratio of 3:1 v/v concentrated sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) to hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to digest 0.6 mg of PET (PET 1 and PET 2) bottles individually. They were placed in PFA-coated heating blocks at a hot-plate temperature of 110°C for 14 h, then left at room temperature for 1 h (following the method of Ohnemus et al., 2014). The resulting solutions were filtered and diluted to determine Sb using a Hitachi TM 3030 Plus SEM equipped with EDX Bruker microanalysis system.

ICP-OES characterization

The digestion method to determine total Sb for the PET bottles followed Westerhoff et al. (2008). A sample of 0.50 mg of each PET bottle (PET 1, PET 2, and PET 3) was digested with 8 mL of nitric acid (65%, Sigma-Aldrich) and 3 mL of peroxide hydrogen (30%, Sigma-Aldrich). They were digested on a hot-plate overnight at 35°C and then heated up to 120°C for 1 h. The resulting solutions were filtered and diluted to be analysed by ICP-OES to determine Sb content.

Experimental design and sampling protocol

Three water pH levels were adjusted to 6.5, 7.0, or 7.5 using 1 M HCl and 1 M NaOH. Additionally, these bottles were investigated at different temperatures (25, 40, 50, and 60°C) by placing these bottles in a temperature-controlled incubator (BIOBASE, BOV-T3 incubator). Experiments were conducted over a period of 200 days. The bottles were sampled at set intervals: Day 1, Day 20, Day 50, Day 100, Day 150, and Day 200. Water samples were collected from the bottles using sterilized pipettes and immediately analysed for Sb content.

Statistical analysis

All results were analysed using two-factor analysis (ANOVA) in Microsoft Excel, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Elemental composition of PET bottles

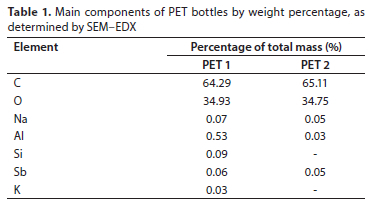

Figure 1 shows the elemental mapping of the inner surfaces of PET 1 and PET 2, obtained using the SEM equipped with EDX microanalysis system. The most abundant element in both types of bottles is carbon (C), which makes up 64.29% and 65.11% of the total mass of PET 1 and PET 2, respectively. Carbon is a key component of all organic polymers, including PET, and its high proportion indicates that the two bottles are primarily composed of carbon-based compounds. Oxygen (O) is the second-most abundant element in both types of bottles. It accounts for 34.93% and 34.75% of the total mass of PET 1 and PET 2, respectively. Oxygen is a crucial component of PET, forming the ester linkages that hold the polymer chains together. Sodium (Na) and aluminium (Al) are present in very small amounts, ranging from 0.05% to 0.07%, and 0.03% to 0.53%, respectively. Silicon (Si) and potassium (K) are found in negligible amounts and only in PET 1, at 0.09%, and 0.03% respectively, indicating that they are not significant components of the PET bottles. The presence of antimony (Sb) in both PET bottles is noteworthy. It was detected in PET 1 and PET 2, albeit in very small amounts, at 0.06%, and 0.05%, respectively (Table 1).

In this study, SEM-EDX detected Sb in very small amounts (0.06% and 0.05%) in PET 1 and PET 2, but its sensitivity makes it less accurate for such low concentrations (especially concentrations lower than 1%). As a result, this study focused the SEM-EDX analysis on PET 1 and PET 2 to ensure the precision and reliability of the measurements. Meanwhile, the presence of Sb in PET bottles was reconfirmed using ICP-OES, which offers higher accuracy for detecting trace amounts, such as those found in this study (0.022-0.844 μg/L).

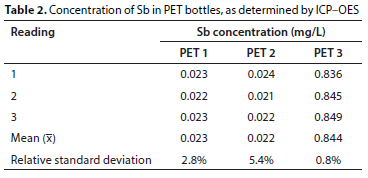

Figure 2 illustrates that ICP-OES is an efficient method for measuring Sb levels in PET bottles. The relative standard deviation was calculated from 3 replicate measurements for each PET bottle. Lower quantities of Sb were recorded in PET 1 and PET 2, at 0.023 μg/L and 0.022 μg/L, respectively. However, in PET 3 the concentration of Sb is much higher, measured at 0.844 μg/L (Table 2). These measurements confirm the presence of Sb in the composition of PET material.

Statistical analysis

The analysis shows the significant effects of both temperature and pH on Sb release from PET materials. The ANOVA revealed that the main effect of temperature was significant (F = 0.954, p = 0.4933), with Sb release increasing as the temperature rose from 25 to 60°C. Similarly, the main effect of pH was significant (F = 0.3867, p = 0.5355), with Sb release varying across pH levels of 6.5, 7, and 7.5. The interaction between temperature and pH was not significant (F = 0.1513, p = 0.9992), indicating the effects of these factors on Sb release were independent rather than combined.

The sums of squares (SS) within groups was 30.3429, indicating the overall variation in Sb release among the different temperature and pH conditions. The SS for the interaction between the two factors was 0.526, which was not significant as indicated by the non-significant F ratio and high p value.

The mean square (MS) values provide further insight into the variation attributable to each factor. The MS for the temperature factor was 0.3015, while the MS for the pH factor was 0.1222. These values, along with the corresponding F ratios and p values, confirm that temperature had a stronger effect on Sb release than did pH, although both factors had significant effects overall.

Influence of temperature on antimony release

The effect of temperature on leaching of antimony from PET bottles as a function of time was investigated at different temperatures (25, 40, 50 and 60°C), for a container with a volume of 0.33 L. Sb concentration for PET 1 was 0.02 μg/L at 25°C and increased steadily to 0.97 μg/L after 200 days. The PET 2 bottle had only been stored for 3 weeks but had an initial Sb concentration of 0.10 μg/L at 60°C. There is a significant difference between Sb content as a function of temperature. Antimony leaching from PET 3 increased after 200 days to a level 4 times higher than that measured on Day 50 at 60°C, from 0.52 μg/L to 2.14 μg/L. In addition, the antimony concentrations for PET 1 and PET 2 at 50°C increased from 0.08 and 0.11 μg/L to 1.56 and 1.21 μg/L, respectively (Fig. 3). The maximum Sb concentration was 2.14 μg/L, at 60°C, which is higher than the most restrictive national limit (for Japan) of 2.00 μg/L. For all bottles (PET 1, PET 2, and PET 3), those with the longest storage time experienced the highest increases in Sb leaching.

Influence of pH value on antimony release

Various factors affect the release of Sb from PET bottles, including pH. The results of this study indicated that filling bottles with drinking water, which typically has a neutral to slightly acidic pH, can lead to increased Sb release compared to more alkaline conditions. These findings reveal that Sb release is inversely related to pH levels, meaning that as pH decreases, the release of Sb increases.

Migration of Sb into normal drinking water for PET 1, PET 2, and PET 3 bottles did not significantly alter the pH of the water from 6 to 8. The levels of antimony released from the three PET bottles after 50 days were all higher than 0.2 μg/L (Fig. 4).

Sb concentration for PET 1 and PET 2 at pH 6.5 was 0.01 and 0.03 μg/L, respectively, and increased to 1.62 and 1.18 μg/L, respectively, after 200 days. The rate of Sb release for PET 3 was found to be the highest and increased from 0.09 μg/L to 1.90 μg/L at pH 6.5 after 200 days.

In general, the total antimony release at the end of 200 days was ranked in the following order: PET 3 > PET 1 > PET 2. The findings of this study regarding Sb release from PET bottles into drinking water corroborate the presence of Sb in the composition of PET bottles, especially for PET 3, in which the weight percentage exceeded 0.05%. Antimony is widely used as a catalyst and stabilizer in most commercial PET bottles and the SEM-EDX results for this study confirm the presence of Sb in the PET bottles sampled. In addition, Fig. 2 shows that inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) is an effective method for detecting Sb content in PET bottles. Leaching of Sb into drinking water is a slow process which persists and increases with time and other factors such as temperature and pH value.

CONCLUSION

Antimony is used as a catalyst and stabilizer in the manufacture of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic, which is the material from which most disposable plastic water bottles and many other plastic items are made. In this study, the presence of antimony on the inner surfaces of PET 1, PET 2, and PET 3 bottles was confirmed by x-ray spectroscopy. In addition, ICP-OES was an eflective method for detecting antimony content of PET bottles.

The level of leaching of antimony from PET bottles into drinking water is influenced by the parameters investigated, i.e. pH value, temperature, and storage time.

The results showed that temperature had a greater influence on Sb leaching than pH, with the highest concentration of 2.14 μg/L observed at 60°C, exceeding the Japanese limit for Sb in drinking water of 2.00 μg/L. While lower pH also increased Sb leaching, reaching 1.9 μg/L at pH 6.5, the effect of temperature was greater. These findings highlight the potential health risks associated with Sb leaching from PET bottles, particularly when stored at elevated temperatures. This study indicates that precautions to avoid antimony contamination should be taken at the manufacturing stage for PET bottles and alternative options should be sought.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author does not have any conflict of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Taibah University for the use of their laboratories and instruments, and are grateful to the central laboratory of the national water company in Madinah for their help in analysing the samples.

REFERENCES

AGHAEE EM, ALIMOHAMMADI M, NABIZADEH R, KHANIKI GJ, NASERI S, MAHVI AH, YAGHMAEIAN K, ASLANI H, NAZMARA S, MAHMOUDI B and GHANI M (2014) Effects of storage time and temperature on the antimony and some trace element release from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) into the bottled drinking water. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 12 133-139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40201-014-0133-3 [ Links ]

BACH C, DAUCHY X, CHAGNON M-C and ETIENNE S (2012) Chemical compounds and toxicological assessments of drinking water stored in polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles: a source of controversy reviewed. Water Res. 46 (3) 571-583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2011.11.062 [ Links ]

CARNEADO S, HERNÁNDEZ-NATAREN E, LÓPEZ-SÁNCHEZ JF and SAHUQUILLO A (2015) Migration of antimony from polyethylene terephthalate used in mineral water bottles. Food Chem. 166 544-550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.041 [ Links ]

DUH B (2002) Effect of antimony catalyst on solid-state polycondensa-tion of poly (ethylene terephthalate). Polymer 43 3147-3154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00138-6 [ Links ]

FAN Y-Y, ZHENG J-L, REN J-H, LUO J, CUI X-Y and MA LQ (2014) Effects of storage temperature and duration on release of antimony and bisphenol A from polyethylene terephthalate drinking water bottles of China. Environ. Pollut. 192 113-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2014.05.012 [ Links ]

GABEL T (1997) Arsenic and antimony: comparative approach on mechanistic toxicology. Chem. Biol. Interact. 107 (3) 131-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00087-2 [ Links ]

GAS (General Authority for Statistics, Saudi Arabia) (2016) Demographic survey. General Authority for Statistics, Riyadh. 33-156. [ Links ]

NORTH EJ and HALDEN RU (2013) Plastics and environmental health: the road ahead. Rev. Environ. Health 28 (1) 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh-2012-0030 [ Links ]

OHNEMUS DC, AURO ME, SHERRELL RM, LAGERSTRÖM M, MORTON PL, TWINING BS, RAUSCHENBERG S and LAM PJ (2014) Laboratory Intercomparison of marine particulate digestions including piranha: A novel chemical method for dissolution of polyethersulfone filters. Limnol. Oceanogr.: Meth. 12 (8) 530-547. https://doi.org/10.4319/lom.2014.12.530 [ Links ]

REIMANN C, BIRKE M and FILZMOSER P (2010) Bottled drinking water: water contamination from bottle materials (glass, hard PET, soft PET), the influence of colour and acidification. Appl. Geochem. 25 (7) 1030-1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeochem.2010.04.009 [ Links ]

SÁNCHEZ-MARTÍNEZ M, PÉREZ-CORONA T, CÁMARA C and MADRID Y (2013) Migration of antimony from PET containers into regulated EU food simulants. Food Chem. 141 (2) 816-822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.03.067 [ Links ]

SHOTYK W, KRACHLER M and CHEN B (2006) Contamination of Canadian and European bottled waters with antimony leaching from PET containers. J. Environ. Monit. 8 288-292. https://doi.org/10.1039/B517844B [ Links ]

SHOTYK W and KRACHLER M (2007) Contamination of bottled waters with antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) increases upon storage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41 1560-1563. https://doi.org/10.1021/es061511 [ Links ]

WESTERHOFF P, PRAPAIPONG P, SHOCK E and HILLAIREAU A (2008) Antimony leaching from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic used for bottled drinking water. Water Res. 42 (3) 551-556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2007.07.048 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Yassin TH Mehdar

Email: ymehdar@taibahu.edu.sa

Received: 27 February 2024

Accepted: 26 February 2025