Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Higher Education

On-line version ISSN 1753-5913

S. Afr. J. High. Educ. vol.38 n.6 Stellenbosch Nov./Dec. 2024

https://doi.org/10.20853/38-6-6005

GENERAL ARTICLES

A paradigm shift in collaborative learning: insights from the theory of collaborative advantage for inclusive and engaging pedagogical design

B.Verster

Department of Urban and Regional Planning Cape Peninsula University of Technology Cape Town, South Africa http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1425-4258

ABSTRACT

Collaborative or group work is a widely-used learning strategy in undergraduate studies, yet it is often met with resistance. Previous research on the topic identified the complexity of collaborative learning strategies as a significant concern for both instructors and students. In response, this article employs the theory of collaborative advantage (and collaborative inertia) to explore a collaborative learning event and illuminate the complexities and advantages that students might encounter. Based on the case study method, the article presents four pedagogical design propositions: (1) design for co-constructing goals, (2) learning-support frameworks as magnifiers, (3) attentiveness to culturally diverse voices, and (4) learning designed for power dynamics. It is argued that these design propositions can assist in fostering collaborative awareness in various disciplines and subject areas.

Keywords: collaborative learning, theory of collaborative advantage, collaborative inertia, ethic of car, collaboration as a social practice

INTRODUCTION

Formal and informal student feedback over many years, supported by literature on the topic (Wenger 1998; Laurillard 2012; Herrington, Reeves & Oliver 2014), confirms that students are generally not in favour of collaborative learning. The reasons for this are multiple but hinge mainly on the highly complex challenges which face both instructors and students when engaging in collaborative learning. In collaborative learning events, instructors and students are confronted with a complex context made up of, amongst other factors, students with differing types of knowledge and skill sets, differing collaborative customs and cultures, and differing viewpoints about power and responsibilities. Such complexities, if not attended to and carefully negotiated, can result in friction and conflict. For example, one of the most prevalent issues that students continuously raise in their feedback is the unequal share of the workload with some students carrying a larger portion of the load - what Lee and Yang (2020, 1) refer to as "social loafing". This can be considered the result of the power dynamics and sense of responsibility within the group not having been pre-negotiated.

A further concern regarding collaborative learning is that higher education systems, in general, still value the individual student contribution above the collective. An example of this is the focus on individual grades which stands in contrast to Wenger's (1998, 4) position of learning as a "fundamentally social phenomenon...learning as social participation". The concept of learning as a social event inspired this explorative article, and the theory of collaborative advantage (Huxham 2003; Huxham & Vangen 2013; Vangen & Huxham 2013) was used to uncover the complexities and opportunities which students experience within an in-person collaborative learning event.

The relevance of the in-person classroom setting might be questionable in the context of the recent global move in higher education towards remote and online learning, but I argue for the value of a hybrid model of learning in which in-person learning cannot be fully substituted by the online learning space. A body of research is growing which focuses attention on negative perceptions of the online learning space (Adnan & Anwar 2020; Paulsen & McCormick 2020; Dhawan 2020; Chandra 2021; Kaufmann & Vallade 2022). One of the common threads in this literature is that, although students feel that group work can easily be completed online (Adnan and Anwar 2020, 48), upon closer inspection it is clear that they are referring to cooperative learning rather than collaborative learning as group work pedagogy. The main difference between cooperative and collaborative learning is captured by Bruffee (1995, 12) who argues that "different assumptions about the nature and authority of knowledge" are being made. During cooperative learning knowledge production can be identified and assigned to individuals in the group, whereas during collaborative learning knowledge production occurs in the community; thus no individual can lay claim to it. This distinction focuses on the foundational importance of community in collaborative learning, but a sense of community - trust, solidarity, responsibility, attentiveness - does not lend itself to being easily translated to the online learning space. For this reason, a hybrid learning approach, with a focus on pockets of in-person collaborative learning, was used for the learning event presented in this article.

A case study research method was applied to the case of a collaborative learning event that was repeated every year for three years. The data were drawn from both artifacts that student groups produced, as well as individual and collective reflective write-ups. The study's participant pool consisted of 81 fourth-year urban planning students made up of 28 students in the first year, 24 students in the second year, and 29 students in the third year of the project roll-out.

The research explored student experiences of a collaborative learning event. These experiences were analysed by employing the theory of collaborative awareness to formulate propositions that may contribute to both a more positive learning experience and also embrace the complexities associated with collaborative learning.

The article is structured by first linking the function of collaboration with the urban planning discipline. Next, the theory of collaborative advantage is introduced and then the case study method and project roll-out are discussed. The article concludes with the four concepts of the theory of collaborative advantage being put into conversation with the collected data to reveal pedagogical design propositions for a collaborative learning event.

COLLABORATION AND THE URBAN PLANNING FUNCTION

As with many professional disciplines in the 21st-century world-of-work context, collaboration is considered a threshold concept (Child and Shaw 2015) - which also applies to urban planning and thus requires a threshold ability of urban planning students. Collaboration manifests in the urban planning practice as public participation - or community engagement/citizen participation - and is informed by participatory planning approaches. The main objective of this approach is to empower communities as key partners in the spatial development process.

Urban planners are tasked with focusing attention on public interest as the dominant driver in political and socio-economic decision-making. This is echoed by the Integrated Urban Development Framework policy that calls for "empowering active communities" (South Africa 2016). To realise this task of empowering active communities - which, sadly, is currently lacking in the South African context - urban planning students need to understand and experience the complexities associated with participatory or collaborative planning through collaborative learning strategies.

THE THEORY OF COLLABORATIVE ADVANTAGE (AND COLLABORATIVE INERTIA)

In this article, the theory of collaborative advantage (and collaborative inertia) is used to explore collaborative awareness and collaborative abilities in a learning event. To understand collaborative advantage, Vangen and Huxhum (2013, 52) point out that "[t]he theory is structured around a tension between collaborative advantage - the synergy that can be created through joint working - and collaborative inertia - the tendency for collaborative activities to be frustratingly slow to produce output or uncomfortably conflict-ridden". It should be noted that, although the authors refer to the theory as "the theory of collaborative advantage", they do acknowledge the importance of collaborative inertia as a realistic part of collaboration. Therefore, I have opted to include (although in brackets) regular references to collaborative inertia.

I focused my attention on the four main concepts that Huxham and Vangen (2013) offer as indicative of a collaborative situation, namely, managing goals, managing trust, managing cultural diversity and leadership.

The first concept of managing goals is recognised in the literature (for instance, Bruffee 1999; Dirkinck-Holmfeld, Hodgson and McConnell 2012; Verster 2020) as a fundamental building block of the collaborative situation. Some key questions to be considered are: How do you set goals? What and who influences and shapes the goals? How do you manage shifts and changes in goals? The conventional practice of the instructor setting the goals and objectives for a student assignment needs reconsideration to include student input in goal setting. By sharing the responsibility for developing the goals and objectives of the learning event, student voices and concerns are foregrounded from the outset. This can become an activity in student empowerment.

The second concept to consider is managing trust. Two particular key questions are: Which activities help build trust? How do you manage a break in trust? Vangen and Huxham (2013) highlight two considerations when building a trusting relationship: "formation of expectations" and "risk-taking". Moving through the learning activity from a point of low risk to one of higher risk is essential to ease students into the development of a risk appetite. Another important quality of trust to consider is that it takes time to develop: students should share experiences that showcase their worth to the group. A scaffolded assignment approach with initial low-risk activities lay the foundation for trust-based collaboration. The interrelatedness of trust and risk-taking within a group is summarised by Vangen and Huxham (2013, 57) as follows: "[A]s trust develops it becomes a means for dealing with risk".

The third concept, managing cultural diversity, has special application to the multilingual (South Africa has 12 officially recognised languages) and ethnically diverse South African educational space. The possibility of cultural differences causing conflict and misunderstanding suggests the potential of cultural diversity contributing more to collaborative inertia than to a collaborative advantage. However, the potential for cultural diversity to bring out creativity and an enriched understanding of context cannot be underestimated.

The final concept focuses attention on leadership. Vangen and Huxham (2013, 63) offer the following rationale for moving away from the traditional leader-follower dichotomy: "Leadership is thus concerned with mechanisms of "making things happen" ". This would then also imply that, within the collaborative situation, leadership will and should change depending on the expertise and resources available to the individuals. This would respond to the dynamic nature of collaborative learning. The learning event presented in this article did not specify roles (for example, group leader, literature specialist, time manager, secretary/scribe, graphics guru, technology specialist) as it was assumed that this might inhibit a student to step over the threshold of his or her designated function. In turn, this may have implications for the sense of responsibility and who takes responsibility for certain activities.

An important layer of complexity to consider is the fact that the collaborative situation does not only exist amongst individual students within a group but also between student groups and the instructor/lecturer. Managing goals, trust, cultural diversity and leadership thus plays out not only within the student groups but also through dynamic engagement with a broader context.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of the article is to explore a collaborative learning event by applying the theory of collaborative advantage (and collaborative inertia) in order to make visible possible pedagogical design propositions. These design propositions intend to engage with the complexities of collaborative learning in a pre-emptive manner by purposefully thinking and designing for collaborative awareness.

RESEARCH METHOD

This research project focused on using a theoretical position to unpack and understand the practical complexity of collaborative learning, and by doing so to influence educational practices (Lodico, Spaulding and Voegtle 2010). The case study method was considered appropriate for this project with its focus on theory-as-a-lens, as Yin (2012, xxii) explains the role of theory, when doing case research, as a "mechanism to generalis[e] a case study's results". A case study applies "a process in which a case is examined in detail and analysed in-depth using research tools most appropriate to the enquiry. This is done developmentally... It is highly contextual" (Association of African Planning Schools, 2010, 5). Yin (2009, 18) defines it as "an empirical inquiry about a contemporary phenomenon set within its real-world context". The phenomenon or "case" in this instance was a single learning event, duplicated over three years. The learning environment, as well as the learning experience, was observed and analysed from the perspective of both the instructor and the students. Insights from this deeply contextual case recognised the complexity and uniqueness of the environment (non-human) and the actors (human) within the learning event.

This feature of case study research, namely, to recognise the "context and other complex conditions related to the case being studied" (Yin 2012, 4), aligns with the urban planning principle of always considering a challenge not in isolation but within its immediate and broader context.

The student project that this article draws from was rolled out for three consecutive years with 28 students in the first year, 24 students in the second year and 29 students in the third year participating. This resulted in a participant pool consisting of 81 fourth-year urban planning students at a University of Technology in South Africa. The subject in which this collaborative student project was positioned was Environmental Studies 4. Data for this article were drawn from four sources, firstly, reflective write-ups of both individual students and groups, secondly, populated Ethic of Care (EoC) frameworks (Tronto 1993; 2013) for each student group, thirdly, Collaboration as a Social Practice (CoSoP) conversation boards for each group and finally, from project artifacts. Ethical clearance was given by the relevant university bodies and written consent was obtained from the participants.

PROJECT ROLLOUT: A PROCESS OF CREATIVE, COLLABORATIVE MEANING-MAKING

An assignment with the title "A process of creative, collaborative meaning-making: the case of public participation in environmental management" was put to students through a series of online, but for the most part in-person, learning activities. The primary objective of this assignment was to develop a new concept to describe the entrenched notion of public participation - thus creating new meaning and understanding. Learning activities focusing on creativity and collaboration were used as stimuli for newness to emerge. It should be noted that adding new, original knowledge to the existing body of knowledge, as was demanded by this assignment, is an arduous and intimidating task for even seasoned students. I had to take special care with how this assignment was scaffolded and how trust and responsibility were shared between me, as an instructor, and the students. The first phase of the learning event involved applying Costandius's (2019) flow exercise as a "conceptual gateway that opens up previously inaccessible ways of thinking about something" (Meyer and Land 2005, 373). The flow exercise was developed on the premise of using seemingly unrelated elements to stimulate a creative and alternative (new) way of thinking about a concept. This process enables the exploration of deeper meaning - and through such deeper meaning also exposes for consideration characteristics and issues that are not typically assigned to a specific concept. The concept, in this case, was public participation.

In the first iteration of the flow exercise, students were tasked with individually developing a poster in response to the above (Figure 1) and also developing a simple icon that represented their new concept. They had to write a paragraph to explain the new concept and icon.

Focusing attention on the "collaborative situation" as part of the primary learning objective, student groups needed to be formed in a meaningful manner. The meaningful manner in this case refers to constructing groups through a common and shared understanding of a concept. The expectation is that this will then be the "glue" that the groups start with. How groups were formulated: Individual posters (with student names having been replaced by anonymous codes) were displayed in class for all students to view. Students were asked to study the other posters and identify three to four poster codes that resonated with their own thinking about public participation. Special interest groups (SIGs) of three to four students were developed based on the common themes that resonated with them.

A second iteration of the flow exercise was done in these SIGs and the individual concepts and icons were now developed into a group concept and icon.

The second phase of the learning event required engaging with literature to develop a deeper understanding of the new concept. This was represented by a formal poster. Questions to which SIGs had to respond in the poster were: How is this new concept similar to public participation? How is it different? How can it enrich current practices? Throughout the learning event, groups had to reflect on their collaboration by making use of the CoSoP board (Verster 2020) and the EoC framework (Tronto 1993; 2013).

The CoSoP board and the EoC framework were used in the learning event to foreground participatory, or collaborative, ways of engagement. The CoSoP board is a tool to assist with making visible the abstract parts, or dimensions, of collaboration that are typically assumed and hidden. The five dimensions of the CoSoP board are:

• Relational actions: the collective habits of collaboration and the actions that support (or do not support) relations within a collaborative learning event - that which you "do" in a collaborative situation.

• Entities: those necessary elements and settings that assist (or do not assist) collaborative learning - that which you "use", such as technology, literature, knowledge, etc.

• Sense-making: those influences that shape what makes sense to the individual and group - why you "do" and "use".

• Interrelatedness: an awareness of how relational actions, entities and sense-making work together or against each other in a collaborative situation.

• Structuring tensions: the foundation of determining the nature of collaboration to include dimensions, such as power, consensus, context and scale.

These five dimensions assist when reflecting on the individual's and the group's collaborative engagement before, during and after the collaborative event. Tronto's EoC framework, on the other hand, provides "moral elements and perspectives on human interaction.. .and collaborative work" (Collett et al 2018, 121). The moral elements of both care-giving and care-receiving are: attentiveness, responsibility, competence, responsiveness, trust and solidarity. Students were tasked with making use of and reflecting on these collaborative tools as part of their assignment.

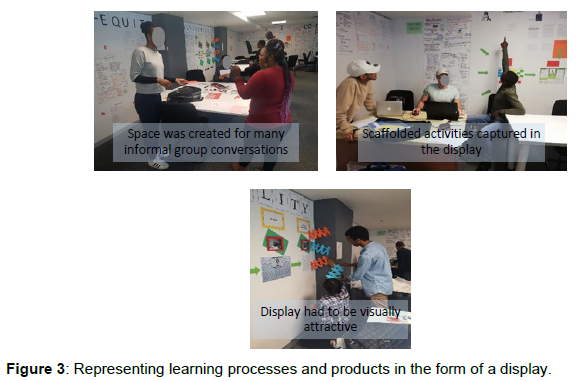

The third phase of the learning event was to create displays of all the activities, as well as artifacts produced (individual posters, individual and combined icons, completed CoSoP boards, write-ups to explain the new concept, formal posters, group reflections using the EoC framework). These displays were first put up in their class, but due to a request from students from other disciplines in the building, the displays were moved to the passages. This was repeated in the second year of the project. The displays were used as a method of making learning visible and shareable.

In summary, students were challenged in this learning event to come up with new and innovative concepts of the well-established and foundational planning notion of public participation. Some of the new concepts with which the student groups came up were Inclu-Equity (wordplay on inclusivity and equity), Collaborability (ability to collaborate) and Joint-Movement (jointly moving together). These concepts are creative, bold and responsive to our Southern context.

STUDENT EXPERIENCES AND REFLECTIONS AS "COLLABORATIVE ADVANTAGES" AND "COLLABORATIVE INERTIA"

As referred to and discussed in a previous section, Huxham and Vangen (2013, 23) understand/describe the essence of collaborative advantage as follows: "[S]omething has to be achieved that could not have been attained by any of the organizations acting alone". With regard to collaborative inertia these authors state the following: "[T]he output from collaborative arrangements often appears to be negligible or the rate of output to be extremely slow. Even where successful outcomes are reported, stories of pain and hard grind are often integral to the success achieved".

It should be noted that the student's written reflections were not done with specifically the four theoretical concepts of managing goals, trust, cultural diversity and leadership in mind. Instead, students were simply asked to reflect on those elements and activities that enabled or disenabled collaborative learning.

Student's reflective write-ups as data were randomly assigned a number and are represented in the following text as, for example, (Student 22).

The following section presents a consideration of the dimensions of the theory of collaborative advantage (and collaborative inertia) and the data drawn from this collaborative learning event.

Managing Goals

Although, as mentioned earlier, goal-setting is considered in the literature as fundamental to the success of a collaborative endeavour, students were, to a large extent, unaware of goal-setting in their reflections. They did, however, mention those structural learning elements that either advanced or restricted their learning goals.

Collaborative advantage with regard to managing goals manifested in indirect ways in the students' reflections. The following quote recognises the goal of the first activity of identifying group members.

"The first exercise whereby we had to develop posters, gave us a chance to judge someone based only on the quality and understanding of their work and how it relates to us as we did not see their names." (Student 4)

Vangen and Huxham (2013) refer to the above as authenticity-seeking - a dimension of the concept of managing goals. This is where the collaborators (students) gauge each

other, so to speak, to determine either a genuine or pseudo level of authenticity.

A goal that was not made explicit to students was to slow down the learning process.

For this reason, a decision was taken at the beginning stages of the learning activity to exclude any technology which typically leads to "finding the answer" and finding other people's opinions instead of tapping into the student's own understanding, positioning and lived knowledge of the topic.

"I was forced to think of concepts that I would have probably never thought of had I had access to Google." (Student 5)

This was also an exercise in empowerment and recognising the students' pre-knowledge as central and essential to their learning. Furthermore, it was also meant to demonstrate how one's thinking about and knowledge of a topic can be enriched by collaborating with others. The development of the individual icons into a more complex group icon is a case in point (see Figure 4).

Managing goals as collaborative inertia are captured by the following: ".. .the assignment process was confusing at first". (Student 7)

".. .the first task that led to the creation of a poster was a way for us to bridge the gap/get over the uncomfortability [sic] to be open-minded about the task that follows." (Student 15)

".it was a break-away from the norm of how I would normally proceed with an assignment, which was uncomfortable because the anticipated outcome was not clear". (Student 2)

"Confusing" and "uncomfortable" might be a result of the students not understanding "relevance" as a dimension of managing goals (Vangen and Huxham 2013, 57). Although the authors recognise the challenge in predetermining relevance, a scaffolded and collaborative (thus all role-players included) process of goal-setting might assist to clarify "relevance" from the outset of the collaborative learning activity.

Vangen and Huxham (2013, 58) link the above with the dimension of "overtness" of goals - as in being unstated or hidden - when they maintain that "there may be limited opportunities to explicitly discuss all potentially relevant goals in an open forum, many goals go unstated even when there is no intent to hide them".

Managing Trust

As mentioned previously, expectations and managing risk or risk-taking are directly associated with levels of trust in a group. Activities that demonstrate students' strengths

and weaknesses help the group know what to expect from each other.

"Developing an icon and concept gave [us] the chance to brainstorm together as a group, we were given a light exercise of processing our thoughts of a combined overall character and aligned goal". (Student 7)

"We were all more or less on the same page from the start as we identified or had the same important elements that was [sic] important to us." (Student 11)

"At first, I was a bit confused as to what was going on, but I realised I needed to let the process unfold." (Student 22)

Trust is inextricably linked with both risk-taking and a sense of responsibility as, if a student does not meet his or her responsibilities towards the group, there will be a break in trust.

"Working in collaboration adds value to a task because as an individual I do not want [to] disappoint the group. I need to pay attention and express my view at all times to finish the task at hand successfully." (Student 1)

Student reflections mentioned concerns regarding the discomfort that came with this new way of learning. Collaborative inertia, as part of the concept of managing trust, is captured by the following student's reflection:

"I felt a little anxious and nervous because I did not know what to expect." (Student 7)

Not surprisingly, trust was highlighted as the most prominent issue under the rubric of collaborative inertia:

"...the group reflection helped me to see I'm not the only one struggling". (Student 1)

Levels of newness in the learning event thus create uncertainty, discomfort and anxiety. These emotions can become debilitating when trust in the group is weak. However, if trust amongst each other is strong and a feeling of solidarity has been developed, then these emotional qualities can be the fertile ground for growth and development. As the saying goes, "out of adversity comes opportunity".

Managing Cultural Diversity

Although it was expected that cultural diversity would be prominent in a multi-cultural South African learning space, the extent to which students were aware of its presence as both collaborative advantage and inertia was surprising.

Concerning collaborative advantage, the following quotes highlight an appreciation of what Vangen and Huxham (2013, 65) call "culture as one of the resources that may lead to synergistic gains".

"This first stage was important as I could determine which of my classmates shared or had a similar view about my own and I could choose to possibly be in a group with them". (Student 2)

"This exercise has taught me that engaging with other individuals and learning to understand their various perspectives, further enriched my own." (Student 17)

"Diversified groups that include a range of talents, backgrounds, learning styles, ideas, and experiences are the best in the sense that knowledge and skills are being shared among group members." (Student 11)

A tension that was identified by students' reflections was the focus on either sameness and/or difference in the group dynamic. The learning event allowed both! This leads usto the collaborative inertia issues that students raised:

"Working in collaboration with a group and engaging with the board was challenging. This is because there was a combination of voices and ideas trying to populate the [CoSoP] board.. .The challenge lies in that everyone has various personal lived experiences, knowledge and understanding of the profession." (Student 20)

".cultural differences led to some sort of conflict between group members." (Student 13)

Vangen and Huxham (2013) refer to the above as "agency tension", as cultural tensions exist at an interpersonal level. This creates an opportunity in the collaborative learning event to develop mitigation strategies for this typical challenge associated with collaboration.

We used reflections as a continuous process (not an end-of-activity exercise), through both the CoSoP board and EoC framework, to identify and engage with tensions.

"I have never conducted a group reflection before, and I found it challenging due to the various personal views generated by the group members." (Student 13)

"However, what made this process much more direct and specific was the use of the ethic of care framework. This framework directed the group reflection about how we provide and receive comments and feedback to each other." (Student 13)

Managing Leadership

Leadership, as with the other concepts, has many dimensions, but one of the most influential ones, according to Vangen and Huxham (2013), is the fact that leadership does not focus attention on the leader but rather on the activity of "making things happen".

Student reflections recognised this quality as part of the collaborative advantage by stating the following:

"We were all focused on what needed to be done so working in a group for me was not that challenging because there was no power struggle or tension." (Student 21)

"Because we already did some work on our individual concepts and icons before getting to the group, I felt I can already contribute something, and that was my focus, to share with my group what I have already done". (Student 14) "This group exercise was an interesting one for me, and I have never had this experience in a group exercise before. This experience was different because all group members came into the group on the same level playing field." (Student 14)

Of course, leadership and the associated power dynamic also make room for what Vangen and Huxham (2013) termed "collaborative thuggery" to capture the collaborative inertia elements. Student reflections were very vocal about these issues.

".. .how one's views can be easily ignored as a result of power dynamics." (Student 3)

"A lack of validation as a result of distrust. But the matter was discussed with the subject lecturer and all individuals overcame this obstacle". (Student 16)

"... some students had hidden agendas in the group - to do as little as possible." (Student 8)

The above concerns were very real in the collaborative learning event, and even though all possible precautions were taken to mitigate them, they still manifested. Most of them can be attributed to what Vangen and Huxham (2013, 58) call "real and perceived power imbalances" which need special attention within the collaborative event.

Reflections on the learning benefits and value of the CoSoP and EoC Frameworks

The following student reflections summarise the general feeling about the use of practical frameworks to guide student engagement. Two lectures were given on these frameworks to introduce and familiarise students with them before operationalising the frameworks as part of the collaborative learning event.

"The completion of the CoSoP Conversation Board added value to our development as a group and we realised that the completion thereof is a continuous effort tracking our thinking as a group during this assignment as well as our thinking about the actual public participation process. It is also important as it can be used as a tool to constantly check on progress made throughout the assignment by responding to various elements". (Student 21)

"This activity in particular added value to my development as this was the first time I learned about this [EoC] framework. It was interesting to see how each phase developed within our group. I have never worked with these students in a group before, it was the first time I did a group activity with my fellow group members and after familiarising myself with the framework, I could determine how each of my group members responded to each phase. This activity is particularly important as it looks at the phases and corresponding moral elements of care as mentioned in the brief, and it was extremely helpful, especially while working as a group. I found myself constantly measuring my responses by the different phases and I think that the associated traits are important and should be something we should strive for". (Student 13)

DISCUSSION: SUGGESTED PEDAGOGICAL DESIGN PROPOSITIONS

Collaborative learning is a highly complex learning strategy and as such warrants a high level of intentionality and care from both the instructor and student groups. In the learning event discussed in this article, scaffolded complexity provided the needed structure to engage with and reflect on the collaborative elements continuously. The following are four propositions, with practical examples drawn from this learning event, offered for creative consideration when designing and rolling out collaborative learning activities.

Design for co-constructing goals

Create opportunities to co-construct and continuously renegotiate group goals by recognising and drawing from students' pre-knowledge and lived experiences. Goals are shaped and influenced by the knowledge position that a student occupies. A practical example of this proposition is first to draw from the individual students' pre-knowledge as a means to give voice to them as individuals and thus empower them before they start the group work. This will set the individual up, so to speak, to make a meaningful contribution from the outset. This was done in the student project by way of the first individual iteration of Costandius's flow exercise. Further, create space for continuous group reflection and recalibration of goals by making use of a framework, such as the CoSoP board, as an integral part of the student project.

Learning-support frameworks as magnifiers

The application of learning-support frameworks can assist students to recognise mutual expectations when engaging with complex and sometimes hidden aspects of collaboration and group work. For example, the responsibility of caregiving, as well as being deliberate with your care needs or care expectations (which Tronto refers to as "care-receiving"), is foregrounded through the EoC framework. This is typically a hidden activity and only comes to the fore when students' care needs are not met. A standard student response, when confronted with a lack of caregiving, would be "I did not know; you did not say anything". A further issue is that of risk-taking, in which case students can be familiarised with the benefits of taking collective risks by grounding risk-taking in trust and solidarity. By introducing the EoC framework from the outset of the project, risk, such as a student representing the group in an activity outside their comfort zone, was mitigated by "caring with" or "patterns of care" (Tronto 1993; 2013). Trust and solidarity are developed over time as a form of social cohesion which means that all the small collaborative tasks within the project eventually add up as social cohesion exercises over time.

Attentiveness to culturally diverse voices

Pay careful attention to the rich contribution that culturally diverse voices can make to a collaborative learning event by creating structured opportunities for exploration. Although cultural diversity could result in interpersonal tensions, mitigation strategies, such as searching for a shared understanding at the beginning of the project (through the group formation activity in this case study), provide a foundation for managing tensions.

Learning designed for power dynamics

Design the learning event with power dynamics in mind. One way would be to reframe the concept of leadership by emphasising the objective of "making things happen", as such an approach draws on the EoC framework to ensure solidarity and shared responsibility. This creates an opportunity for leadership to change hands - or be shared, depending on the activity and requirements.

How the above propositions play out in the pedagogical design of a learning event is highly dependent on contextual and numerous other variables. As such, spaces in the form of reflective activities should be created within the learning event to recalibrate and make the necessary adjustments by both the students and the lecturer.

CONCLUSION

Bruffee (1995, 14) refers to John Dewey's "associated life" concept to summarise attitudes to collaboration as "the people involved almost always have to undergo some kind of change. Working together well doesn't come naturally. It's something we learn how to do." Because, in most cases, students are not naturally collaborative, it is important to reflect on collaborative learning events to highlight the themes/areas that cause anxiety and inertia, as well as those that have the potential to result in reward and advantage. For this reason, the theory of collaborative advantage (and collaborative inertia) was used to engage with a collaborative learning event.

I have come to realise that collaborative inertia elements will emerge no matter the level of preplanning and that it might be better to co-construct mitigation measures with the student groups as the challenges unfold. Furthermore, collaborative inertia seems to be focused on emotional constructs and not so much on practical aspects. This is concerning because emotional aspects are not particularly visible in a learning event and thus need to be made visible. The Ethic of Care framework, as a tool for continuous reflection and a way of keeping one's finger on the pulse, assisted with this process. Thus a key lesson taken from this learning event is the importance of designing with intentionality in mind. By using frameworks, such as the EoC and CoSoP, the importance of collaboration as a continuous process that warrants care elements, reflection, and re-calibration is foregrounded.

In closing, this article argues for a paradigm shift through the four pedagogical design propositions presented here, which can serve as a valuable resource for fostering collaborative awareness and addressing the intricate dynamics of collaborative learning.

REFERENCES

Adnan, M. and Anwar, K. 2020. "Online Learning amid the COVID-19 Pandemic, Students' Perspectives." Online Submission, 2(1): 45-51. [ Links ]

Association of African Planning Schools. 2010. "Guidelines for case study research and teaching." https://africanplanningschools.org.za/images/downloads/handbooks-and-guides/AAPS-Guidelines-for-Case-Study-Research-and-Teaching.pdf [ Links ]

Bruffee, K.A. 1995. "Sharing our toys, Cooperative learning versus collaborative learning." Change, The Magazine of Higher Learning, 27(1): 12-18. [ Links ]

Bruffee, K.A. 1999. "Collaborative learning, Higher education, interdependence, and the authority of knowledge." Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. [ Links ]

Chandra, Y. 2021. "Online education during COVID-19: perception of academic stress and emotional intelligence coping strategies among college students." Asian Education and Development studies, 10(2): 229-238. [ Links ]

Child, S. and Shaw, S. 2015. "Collaboration in the 21st century: Implications for assessment." Economics, 21: 17-22. [ Links ]

Collett, K. S., Van den Berg, C.L., Verster, B., and Bozalek, V. 2018. "Incubating a slow pedagogy in professional academic development: An ethics of care perspective." South African Journal of Higher Education 32(6): 117-136. [ Links ]

Costandius, E. 2019. "Fostering the conditions for creative concept development." Cogent Education, 6(1): 1700737. [ Links ]

Dhawan, S. 2020. "Online learning, A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis." Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1): 5-22. [ Links ]

Dirkinck-Holmfeld, L., Hodgson, V., and McConnell, D. 2012. "Exploring the theory, pedagogy and practice of networked learning." New York, Springer. [ Links ]

Herrington, J., Reeves, T.C. and Oliver, R. 2014. "Authentic Learning Environments." In Spector, J., Merrill, M., Elen, J. and Bishop M. (eds). Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. New York, Springer. [ Links ]

Huxham, C. 2003. "Theorizing collaboration practice." Public management review, 5(3): 401-423. [ Links ]

Huxham, C. and Vangen, S. 2013. "Managing to collaborate, The theory and practice of collaborative advantage." New York, Routledge. [ Links ]

Kaufmann, R. and Vallade, J. 2022. "Exploring connections in the online learning environment: student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness." Interactive Learning Environments, 30(10): 1794-1808. [ Links ]

Laurillard, D. 2012. "Teaching as a design science, building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology." Oxford, Routledge. [ Links ]

Lee, W.W.S. and Yang, M. 2020. "Effective collaborative learning from Chinese students" perspective: a qualitative study in a teacher-training course." Teaching in Higher Education, 1-17. [ Links ]

Lodico, M., G., Spaulding, D., T. and Voegtle, K., H. 2010. "Methods in Educational Research, From Theory to Practice." Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-58869-7. [ Links ]

Meyer, J.H. and Land, R. 2005. "Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge, Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning." Higher education, 49(3): 373-388. [ Links ]

Paulsen, J. and McCormick, A.C. 2020. "Reassessing disparities in online learner student engagement in higher education." Educational Researcher, 49(1): 20-29. [ Links ]

South Africa. 2016. "Integrated Urban Development Framework." Online available at, http://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/u16/010416_IUDF_Implementation%20Plan_final.pdf [ Links ]

Tronto, J. 1993. "Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care." New York and London, Routledge. [ Links ]

Tronto, J. 2013. "Caring Democracy. In and beyond new labour: towards a new political ethic of care." Critical Social Policy, 21(4): 467-93. [ Links ]

Vangen S. and Huxham, C. 2013. "Building and Using the Theory of Collaborative Advantage." In Network Theory in the Public Sector, Building New Theoretical Frameworks. Eds. R., Keast, M., Mandell and R. Agranoff. New York, Taylor and Francis, 51-67. [ Links ]

Verster, B. 2020. "Reimagining collaboration in urban planning through a social practice lens: Towards a conceptual framework." Town and Regional Planning 76 (2020): 86-96. [ Links ]

Wenger, E. 1998. "Communities of practice, learning as a social system." Systems Thinker, 9(5): 2-6. [ Links ]

Yin, R.K. 2009. "How to do better case studies." The SAGE handbook of applied social research methods, California, SAGE, 254-282. [ Links ]

Yin, R.K. 2012. "Case study methods." In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA Handbook of research methods in Psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs, Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. American Psychological Association. [ Links ]