Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Journal of Literary Studies

On-line version ISSN 1753-5387Print version ISSN 0256-4718

JLS vol.41 n.1 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.25159/1753-5387/18499

ARTICLE

"A Talent for Wonder": The Performatist Double Frame and Characters with Autistic Traits in Marlene van Niekerk's Short Story Oeuvre

"'n Talent vir verwondering": Die performatistiese dubbelraam en karakters met outistiese eienskappe in Marlene van Niekerk se kortverhaal-oeuvre

Janien Linde

North-West University, South Africa. janien.linde@nwu.ac.za; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2361-8957

ABSTRACT

This article explores Raoul Eshelman's concept of the performatist double frame as it manifests in Marlene van Niekerk's short story oeuvre, with a particular focus on her depiction of characters with autistic traits in two volumes of short stories: Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het (1992) and Die sneeuslaper (2010). Eshelman's theory, which hinges on the use of narrative framing to compel readers to adopt a single interpretive stance, provides a lens through which Van Niekerk's narratives can be analysed. In Van Niekerk's short stories these characters are integral to the construction of framed scenarios where the reader is drawn into accepting the story's fantastical elements as plausible, thereby suspending scepticism. The article argues that this narrative strategy facilitates a performative engagement with the text, allowing the reader to momentarily experience the world of the story as real, and to consequently feel a sense of enchantment. Furthermore, the article identifies a significant shift in Van Niekerk's short story oeuvre, wherein earlier portrayals of characters with autistic traits emphasised their marginalisation and expulsion from society, while later works position these characters as central figures who drive the narrative's engagement with themes of belief, perception, and inspiration. This evolution reflects a nuanced approach to the depiction of characters who display intellectual "otherness" as well as the use of narrative framing, and highlights Van Niekerk's contribution to contemporary Afrikaans (and South African) literature as a space for reimagining the boundaries of storytelling.

Keywords: performatist double frame; characters with autistic traits; narrative framing; Marlene van Niekerk; post-postmodernism

OPSOMMING

Hierdie artikel ondersoek Raoul Eshelman se konsep van die performatistiese dubbelraam soos dit manifesteer in Marlene van Niekerk se kortverhaal-oeuvre, met 'n spesifieke fokus op haar voorstelling van karakters met outistiese eienskappe in twee kortverhaalbundels: Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het (1992) en Die sneeuslaper (2010). Eshelman se teorie, wat narratiewe rame gebruik om lesers te dwing om 'n spesifieke interpretasie van die verhaal aan te neem, bied 'n lens waardeur Van Niekerk se vertellings ontleed kan word. Sulke karakters speel 'n integrale rol in Van Niekerk se kortverhale om beraamde narratiewe scenario's te konstrueer waartydens die leser meegevoer word om die fabelagtig elemente in verhaal te aanvaar, en sodoende skeptisisme op te skort. Die artikel argumenteer dat hierdie narratiewe strategie 'n performatiewe betrokkenheid met die teks moontlik maak, waardeur die leser die wêreld van die verhaal as werklik kan ervaar en gevolglik 'n gevoel van betowering kan ervaar. Verder identifiseer die artikel 'n beduidende verskuiwing in Van Niekerk se oeuvre: waar vroeëre voorstellings van karakters met outistiese eienskappe hul marginalisering en uitwerping uit die samelewing beklemtoon het, posisioneer latere werke hierdie karakters as sentrale figure wat die narratief se temas van geloof, persepsie, en inspirasie dryf. Hierdie evolusie weerspieël 'n genuanseerde benadering tot die uitbeelding van karakters wat intellektueel "anders" is sowel as die gebruik van narratiewe beraming, en beklemtoon Van Niekerk se bydrae tot die hedendaagse Suid-Afrikaanse literatuur as 'n ruimte waarin die grense van vertelling herverbeel kan word.

Sleutelwoorde: performatistiese dubbelraam; karakters met outistiese eienskappe; narratiewe beraming; Marlene van Niekerk; post-postmodernisme

Introduction

In her book Hooked (2020), Rita Felski explores what captivates a reader when they read a book. How does a writer manage to write a text that engrosses a reader and makes them temporarily forget about the reality outside of the book? In this article, I present one possible approach to this question by focusing on the performatist influence of characters with autistic traits that repeatedly appear in Marlene van Niekerk's texts. The portrayal of such dense or "opaque" characters, as Raoul Eshelman (2000-2001, 1) describes them, is developed throughout the whole of Van Niekerk's oeuvre into a leitmotif of the pure, uncontaminated, unfathomable, and intuitive view of reality that sometimes accompanies artistic talent. The presence of these characters and their unique abilities and ways of viewing the world allows Van Niekerk to create specific narrative structures that influence and affect how readers experience the stories.

For this article, I specifically focus on characters who display characteristics often associated with people on the autism spectrum. Although I include a short discussion of autism from a literary perspective, and while I do draw on some ideas from disability and autism studies (mainly from Loftis [2015]), I do not examine these characters mainly from a disability studies perspective. The goal of this article is to highlight how the depiction of these types of characters, using Eshelman's notion of performatist framing (reference), ultimately leads the reader to develop, in an affective manner, a certain "talent for wonder" (Van Niekerk 1992, 107), similar to that which these types of characters in Van Niekerk's oeuvre embody and inspire in other characters. The discussion focuses on characters from the two short story collections Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het (1992) and Die sneeuslaper (2010).1

Some Perspectives from Disability Studies

Characters with physical and/or intellectual disabilities have been present in Marlene van Niekerk's oeuvre from the beginning. Although I will be focusing on Van Niekerk's short stories in this article, for the sake of the broader context of her work I am pointing out some examples from her novels, short stories as well as her poetry: the child with Down's syndrome in the poem "Troetelwoorde vir Ogilvie Douglas" (Sprokkelster 1977, 11); Karel Nienaber, the anti-apartheid activist who suffers from hallucinations and tinnitus in the short story "White Noise" (Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het, 1992); Andries Aggenbach in the short story "Andries" (Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het, 1992), a cognitively impaired character described as "below-weight and defenceless sickly and simple-minded"; Lambert Benade from the novel Triomf (1994), whose incestuous origins gifted him with epilepsy, unpredictable aggression, and not much cognition; Agaat with the disabled arm (from the novel Agaat [2004]); Kasper Olwagen in "Die swanefluisteraar," as well as Peter Schreuder from "Die vriend" (both from Die sneeuslaper [2010]), who, based on how Van Niekerk describes them, could both probably be diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum; and lastly the sickly Dutch painter, Adriaen Coorte, with whose paintings Van Niekerk converses ekphrastically in the poetry from Gesant van die mispels (2017).

Although it would be illuminating to explore these characters in Van Niekerk's oeuvre using the broad perspective of disability studies,2 the focus of this article is characters from her short stories who display indications of "cognitive, intellectual, or neurological disabilities" (Osteen 2008, 3)3 and more specifically characters who seem to be on the autistic spectrum. These characters' seemingly autistic traits afford them unique ways of viewing the world, a certain "talent for wonder" (Van Niekerk 1992,107). This is something that other characters in Van Niekerk's short stories initially find alienating, but which later proves to be something to aspire to. Van Niekerk's depiction can be seen as an example of what Sonya Freeman Loftis (2015, 2) calls the "disruptive power" that characters with intellectual or cognitive disabilities have on "normative discourse." This resonates with the way that Van Niekerk incorporates characters with autistic traits into her narratives: they disrupt the normal discourse on intellectual "otherness" and eventually become inspirational. Andries Aggenbach's words from the 1992 text are illuminating in this regard: "There is nothing that can so unnerve a tyrannical order as innocence on two legs, nothing that is experienced as more undermining for the collective self-confidence than a talent for wonder, an attitude of attentiveness- passive, veiled, and disinterested" (Van Niekerk 1992, 107; own emphasis).

Disability studies as an academic field of study has been growing steadily over the last forty years.4 Intellectual, cognitive, and neurological disability has, however, been largely excluded from disability scholarship (see Loftis 2015, 3; Osteen 2008, 3). This stems from the fact that people with intellectual disabilities seem to fall lower on the hierarchy concerning value and quality of human life (Loftis 2015, 3). It is easier to make room in society for physical disabilities than for mental disabilities (Osteen 2008, 4). This is even more true for people on the autism spectrum5 as the condition still eludes conclusive classification. Mark Osteen, a neurodiversity and literary scholar, describes autism spectrum disorder (ASD) as an "extraordinarily unstable category" (Osteen 2008, 10). Despite people with ASD routinely being seen as having a specific set of limiting characteristics such as difficulty with social skills and communication, a limited range of interests, and sensory integration problems (Loftis 2015, 3), some of the abilities that people with ASD display can be empowering. Abilities such as increased focus and memory retention, as well as detail-oriented thinking present unique opportunities (Loftis 2015, 3). Interestingly, Loftis (2015, 4) argues, it is exactly this "tension between disability and ability," or limitation and boundlessness, that draws popular attention from writers and readers alike and adds to the public fascination with autistic characters. Medical humanities scholar Stuart Murray (2008, xvii) describes sentiments surrounding the representation of autism in cultural forms across a wide range of media as follows: "Because it is seemingly beyond current scientific knowledge, and because it evades the popular idea of the rational, autism appears to be otherness in the extreme and, as a consequence, the source of endless fascination" (own emphasis).

It is the depiction, utilisation, and appropriation of this "otherness in the extreme" that Loftis writes about in her seminal work on autism and literature, Imagining Autism:

Fiction and Stereotypes on the Spectrum (2015). Loftis discusses several literary stereotypes often associated with characters deemed autistic, such as the autistic detective (for example Sherlock Holmes), the autistic savant (Henry Higgins in Pygmalion), the autistic victim (Charlie Gordon in Flowers for Algernon), the autistic gothic (Boo Radley in To Kill a Mockingbird), and the autistic child narrator (Christopher Boone in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time). With these examples, Loftis illustrates that autism in fiction is mostly described in terms of that which is lacking, in other words, how an autistic character might lack insight and integration into societal systems and norms. Of particular relevance to my argument in this article is that characters with autism are routinely depicted as either savants or helpless victims, especially in older literary texts (Osteen 2008, 299; also see Loftis's [2015] Chapters 2 and 3 on these stereotypes in popular culture). The stereotypical autistic savant is an extraordinarily gifted detective, Sherlock Holmes being the most well-known example, who saves the day despite their otherness being a social stumbling block, and whose autistic traits lead to destructive coping mechanisms such as addictions, self-isolation, and self-harm. The stereotypical victim is someone whose autism leads to immense suffering and alienation. These two stereotypes regularly go hand in hand: the autist's genius is sometimes depicted as directly to blame for them being tragically and forcefully cast out of society. However, Loftis (2015, 154-155) explains that the aim of her book is also to show and describe how autistic literary characters are increasingly being portrayed positively in terms of what is present and not absent due to their autism. The discussion is led by how autistic subjectivity might be seen as presenting agency and ability, not only disability, absence, and lack. Loftis's book on the complex relationship between disability studies and autism studies, showing that autism studies are increasingly moving away from understanding autism only in disability terms (see also Osteen 2008), serves as background and context to my argument regarding the shift in how Van Niekerk depicts such characters.6

In an interview Van Niekerk admits that she has a soft spot for such "weird characters" (Anon 2006). She wrote affirmatively about the atypical characters from her books that she calls the "backroom children"7 (Van Niekerk 2008, 103; see also Olivier 2011). She is specifically referring to Agaat Lourier and Lambert Benade from the novels Agaat and Triomf, respectively. Although they are not depicted as having autistic traits, per se, their "otherness" seems to afford them the ability to view the world from a different, more creatively fertile point of view. Lambert and Agaat are "buns from the same dough,"8 Van Niekerk writes (2008, 105). Some of the similarities that she mentions are relevant to the arguments made in this article: both Lambert and Agaat are marginal figures; both have a (bodily) disability that makes them "different"; both have much influence in their environments; both are simultaneously fixers or repairers, and demolishers; and both possess "the power to create in free experimental ways" (2008, 105). Referring to Van Niekerk's thoughts on them, Olivier describes Agaat and Lambert as follows: "characters that manage, despite the fact that they are isolated in backrooms, to get a creative grip on their world which grants them a certain type of autonomy" (Olivier 2011, 168; own translation). This description by Olivier links up to how the characters from Van Niekerk's short stories discussed in this article are depicted. Even though certain autistic characteristics have historically been appropriated into erroneous and problematic literary stereotypes (like the ones discussed earlier), some writers (both autistic and neurotypical) have been able to empathetically create autistic characters who have agency and who are able to transcend pigeonholing, as research on literary autism illustrates (see Loftis 2015; Osteen 2008). In my opinion, Van Niekerk is one of those writers, although a certain shift was needed from Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het to Die sneeuslaper in how Van Niekerk depicts characters with autistic traits. My argument is that in Van Niekerk's earlier short stories (those in Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het), characters with what can be read as autistic traits are depicted within the scope of the victim stereotype, but that Van Niekerk's depiction of such characters underwent a noteworthy evolution and that characters from Die sneeuslaper illuminate this shift. My discussion of four specific characters from the two volumes of short stories should illuminate this.

The Shift: From Stereotype to Agency and Admiration

I will illustrate the shift in Van Niekerk's writing by firstly discussing two characters from two different short stories from Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het (1992), Karel Nienaber and Andries Aggenbach, as examples of the victim stereotype. I will then discuss two characters from Die sneeuslaper (2010), Kasper Olwagen from "Die swanefluisteraar and Peter Schreuder from "Die vriend," whose autistic traits are depicted as strengths to be admired and imitated rather than pitied. They are portrayed through what they have, rather than what they lack.

The character Karel in the first short story "White Noise" (Van Niekerk 1992, 1-15) from Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het is an example of the victim stereotype. Karel is an obsessive-compulsive perfectionist who actively partakes in the antiapartheid movement at the beginning of the 1990s. Karel is a "new kind of activist, a 'leftie' with his 'Cultural desk' in the service of the new emerging rulers" (Kannemeyer 2005, 632; own translation) who wants to deliver a message from "the last anti-fascist angel in heaven, who has just died" (Van Niekerk 1992, 11) to the ANC. But when he faints and starts to rant about his visions at the first public meeting of the ANC in forty years, the crowd taunts him. His comrades jump to his rescue and help him to flee. Karel is then diagnosed with tinnitus, which causes him to experience ringing in his ears, distortions of auditory impulses, hallucinations, and phobias. In this narrative, Karel becomes a pathetic figure who lives out an activist fantasy (first with the ANC and later as a campaigner for other tinnitus sufferers) and becomes alienated from other people. Karel is expelled from society because those who were previously close to him feel that he should be avoided. His theatrical and melodramatic messianic attempts to save pre-1994 South Africa and the ANC from collapse are ridiculed.

Another example can be found in the story "Andries" (Van Niekerk 1992, 107-119). Andries Aggenbach is described as a "sapling" who "helplessly and lightly dreamed his way through life" (1992, 108). He is one of the best examples of the simple, autistic, innocent characters that repeatedly appear in Van Niekerk's texts. He is very sensitive, and an artist in his love for sunflowers and gardening. His art is an obsession he uses as a shield against the assaults of reality. His gardening-as-art, however, is appropriated and misused by the ruling powers for their own benefit when the beautiful garden Andries creates at the prison where he works is used for various state functions. The beauty he created is tainted by people's pursuit of personal and political gain. After a disastrous state banquet interrupted by screaming prisoners, Andries himself destroys his garden with a tractor and plough. His hard-earned camaraderie with five kindred spirits in the prison who might all be on the autism spectrum is disrupted in the process. He too becomes an outcast who does not seem to fit into society and ultimately finds solace and joy only in caring for his sunflowers.

Although Karel and Andries try to oppose the tyranny of the societies in which they function, both are eventually sucked back into and levelled by their surroundings. Similar to how Van Niekerk describes the fates of Lambert and Agaat, Karel and Andries ultimately have "roles of lessened potency and subjection to the status quo" (Van Niekerk 2008, 116). They are pseudo-shamans9 (Van Niekerk 2008, 116) who in the end have no power to alter anything in lasting ways, and are cast from society. As a writer, Van Niekerk draws parallels between this impotence and the powerlessness of the "romantic artist" in contemporary times (2008, 116).

Later in Van Niekerk's short story oeuvre, however, there is a notable change regarding the portrayal of this archetype, as well as the symbolic artistic agency that they possess. Where characters with autistic traits in Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het are expelled from society and pitied (albeit ignorantly) for their simple existence, such characters in Die sneeuslaper (2010) transcend the power that society holds over them by leaving something precious behind. They become shaman-like artists who have access to insights beyond human understanding: they can "see" better than the rest of the mortals on earth. In their otherness lies a primal, almost deified knowledge, intuition, and enchantment that an artist is only sometimes privileged to access. The difference between Lambert and Agaat and the characters from Die sneeuslaper, however, is that the latter are actively admired and imitated by other characters. They leave something seemingly transcendent behind, and, importantly, there is someone who tries to understand and interpret it: the artist and author-character Van Niekerk.

Two examples of characters in the collection Die sneeuslaper where this transformation into having shamanistic characteristics is visible are Kasper Olwagen in "Die sneeuslaper" and Peter Schreuder in "Die vriend." Both these characters are initially perceived by the Van Niekerk character10 as being too strange for the world and quite bothersome. However, through the course of both short stories, the Van Niekerk character becomes aware of the exceptional nature of these characters. Both "disappear": Kasper seems to completely vanish from the Van Niekerk character's life, and Peter Schreuder becomes seemingly unapproachable and sits staring at birds in the Van Niekerk character's back garden. But in both cases, the Van Niekerk character feels inspired by the two characters' stories, the art they left behind, and the superhuman insights they seem to have into life.

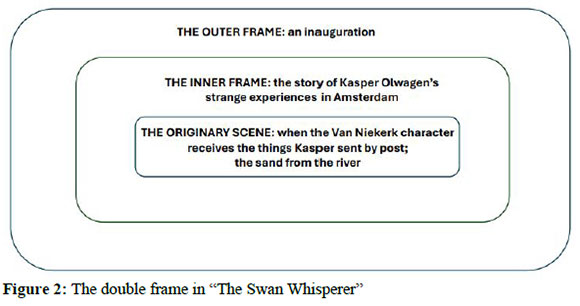

Kasper Olwagen, from the first story, "The Swan Whisperer," in the collection is initially described as a "slight, pale fellow with intense eyes, a high forehead, a delicate mouth," that "his movements seemed somewhat tentative" and that he gives "an impression of fragility." "(I)ntelligent, obsessive, withdrawn, a bookworm who lisped slightly when he was nervous or excited." "There was something old-fashioned about his manner" (2019, 13-14). On the insistence of his creative writing lecturer (the Van Niekerk character), Kasper spends three months in Amsterdam trying to overcome writer's block and to become a "real" writer. During his time in Amsterdam as well as after his supposed return to South Africa, his lecturer receives several enigmatic parcels, including letters detailing Kasper's experiences, a logbook, several cassettes, and an envelope full of river sand. At first, she ignores these parcels but eventually gets drawn into Kasper's account of what happened to him. In the letters, he tells her about his encounters with a homeless man that he names the Swan Whisperer. This man seems to have the ability to communicate with and mesmerise the swans on the canals of Amsterdam. Kasper details how he tried to help this street dweller by taking him into his home and caring for him, and how the Swan Whisperer disappeared without ever saying a word. Kasper tries unsuccessfully to find the strange man, almost freezes to death, and ends up in the hospital with a nervous breakdown. Like the Swan Whisperer, Kasper also disappears without a trace, and his stories captivate his lecturer to such an extent that she travels to the Cederberg mountains (Western Cape) to try to track him down. When she does not find him there, she sits alone by a river and attempts to decipher the strange sound poems recorded on the cassettes that the student sent. She now regards him as a shaman-like artist, someone whose example will inform her work for her for the rest of her life (2019, 42). She writes: "I am the real dummy, you see, the mock-up professor, and God knows who is writing in me. Someone has fitted me with a tongue [...] I sit in my yard and the seasons pass over me. I no longer write novels; I have come to see myself as a translator [of Kasper's sound poems] [...] I barely link words to meaning, because meaning is irrelevant. What is important is the materiality of the words" (2019, 42). She dedicates her "latest [writing] attempt" to Kasper, "the one who taught me everything a writer should be-which is, mind you, something quite different to what a writer should write" (2019, 43; cursive in the original).

Peter Schreuder, from the last story in the collection, "The Friend," is an old college friend of the Van Niekerk character. He is a photographer who suffers from mild epilepsy and a stutter, and who is described as "outlandishly pale, with a roaming gaze, his complexion often tinged by melancholy [...] He had an irregular gait" (Van Niekerk 2019, 157-158). However, when he is busy taking photos, he transforms into a "supple and unpredictable" artist, "as though, in the middle of everyday routine, he was taking part in a parade of miracles" (2019, 157). He enjoys photographing trivialities: "a dripping gutter, a fallen handkerchief, a postbox in the column of shadow cast by a lamppost-as though these things were drenched in the light of revelation" (2019, 157). One day while they are still students, the Van Niekerk character confronts Peter about not taking more politically engaged photos during the turbulent seventies. After a heated exchange of words, Schreuder disappears. Later on, the Van Niekerk character finds out that he has become a world-renowned photographer, artistically capturing societal injustices on film. Every now and then, he reconnects with his old friend "Van" (as he calls the Van Niekerk character) and even unexpectedly appears on her doorstep. At some point, however, he loses his way and begins to receive criticism when his work is described as racist and stereotypical: "shameless pictorial exploitation of the subaltern" (2019, 174). Peter is shattered and unable to cope. The Van Niekerk character tries to help by shifting his focus to nature photography, specifically birds. For a while, the Van Niekerk character is under the impression that he is content. One day he appears on her doorstep unannounced and "with feverish eyes" (2019, 177), dropping off a file with photographs. Then he once again disappears, heading to Europe. Van Niekerk begins to receive puzzling letters from him, telling her that he is following and photographing a homeless man he calls the "die sneeuslaper," "the Snow Sleeper." It turns out that this is the same man who so inspired Kasper Olwagen. Eventually, the Van Niekerk character is summoned to the airport in South Africa to claim Schreuder. He has been deported from the Netherlands and is described by the Dutch authorities as follows: "adult foundling, non-delinquent, illegal, a foreigner, dependent and doli incapax grade 3" (2019, 181). He is also suspected to have multiple personality disorder. "But there is nothing multiple about Schreuder," writes the narrator:

[H]e is singular, a blank slate, and he is no trouble at all. He moves without knowing where he is going, sits without knowing where he is sitting; he is calm and composed, just going with the flow. A big grey-haired child in my back garden with his face aimed at the heavens, breathing calmly. [...] The specialists cannot find any neurological problems. A freak mental standstill, they call it. He is as he is, but he is gone. He will not open his mouth. He refuses. He closes his eyes, as though he is afraid he himself might leak from his sockets. (2019, 182)

She tries to communicate with him, but he does not respond and only makes bird sounds.11 Only when she looks at his nature photos again does she see that the photos are "an essay on absence, full of gusts and slipstreams and the play of enlivened light" (2019, 184). She realises that she never really understood him or his work. She tried to impose her liberation politics and nature conservation as the only valuable aesthetic agendas on him, while he was busy with something much more important and admirable: "the release of all things from their outlines, the negative way" (2019, 184). Before the Van Niekerk character saw her friend as a nuisance and an artist without a worthy cause. Now she sees that she has been stupidly missing the deeper lessons of his life and work: "teachings of the mysterious surfaces of things, the fathomlessness of existence for which not only the photographer but also the writer ultimately bears responsibility" (2019, 184-185). She realises that she was not able to be a friend and companion to him the way that he was for her, and she regrets this.

The shift in Van Niekerk's oeuvre from the first two characters to the second two might seem small, but in the context of the depiction of characters with autistic traits, it represents an important shift that creates interesting new narrative possibilities. It also has implications for Van Niekerk's own writerly views on the influence of the writer in the contemporary moment.

Eshelman's Performatism: The Double Frame, Ostensive Sign, and Performatist Subjectivity

How do Van Niekerk's texts succeed in formal, structural ways to convince the reader to see these two pairs of characters so differently? Why are Karel and Andries victims that are cast out by society, but Kasper and Peter are elevated to something almost transcendent? And what effect does this have on the text and the writer's ability to enthral and engross the reader? Post-postmodernist theorist Raoul Eshelman's performative double frame might present some answers. The argument put forth in this article is that Eshelman's performative double frame presents a practical and structured strategy to achieve a unifying new type of "oneness" (Eshelman 2008, 1) within a text, that is utilised to great effect in these short stories by Van Niekerk.

Eshelman is a German-American literary theorist whose ideas on performatism have been described as epochal and "poignant" within the context of post-postmodernism12(see for example Vermeulen and Van den Akker 2010, 6). According to Eshelman (2008, 1), "the split concept of sign and the strategies of boundary transgression" typically found in postmodern thinking lead to the continual undermining of any form of closure in a work of art. Postmodern, poststructuralist "narrative and visual devices create an immanent, inescapable state of undecidability regarding the truth status" (2008, 1) of an artwork. Performatism, however, is "an epoch in which a unified concept of sign and strategies of closure" have begun, according to Eshelman (2008, 1), to "compete directly with [...] and displace" the basic ("and epistemologically well-founded") suspicion of concepts like meaning, closure, and unity. Thus described, performatism leads to the "hermeneutics of suspicion" that Paul Ricoeur spoke of, making way for a "hermeneutics of affirmation" (Felski 2015, 1). In Hooked (2020) Rita Felski makes similar claims: that there is a "groundswell of voices in the humanities"13who, "with zero nostalgia for the past[,] hope for a less cynical and disenchanted future" (2020, viii). She lists some "catchphrases" (as she calls them) that form part of this movement: "surface reading, new formalisms, the affective turn, the return to beauty." Her contribution to the discussion is the idea of attachment: "how people connect to art and how art connects them to other things" (Felski 2020, viii). Felski's arguments on this topic have however been criticised as being not specific enough concerning discernible textual strategies (see Liming 2020).14 Conversely, Eshelman's performatist framing provides a thought-provoking and useful description of how an author can use specific strategies to create a literary text that creates meaning and closure in such a way that the reader truly does feel attached to, or hooked by, the story.

The way the author achieves this is by deliberately guiding the reader to identify with something unlikely or unbelievable within the text to convince the reader "to believe in spite of yourself (Eshelman 2008, 2). The "performance" in performatism refers to the use of narrative framing, where everything within the frame is transformed into a "performance." The framing provides a certain textual and aesthetic context within which the story takes place, but it also presents the opportunity for the frame to be transcended. Eshelman writes: "[the performance] demonstrates with aesthetic means the possibility of transcending the conditions of a given frame" (2008, 12). A good example of Eshelman's notion of a performative story is Yann Martel's well-known novel, The Life of Pi. In this novel, frames within frames are used to present different levels of the narrative. Martel creates an outer frame in which the main character tells the remarkable story of how he survived in a small boat on the open sea together with a tiger. Within this story, he embeds other stories that seem ever more unbelievable. At the end of the novel, the main character allows his listener to decide for himself if the fantastical story of how he survived is true, or whether he prefers the darker more traumatic version of the events. This means that the narrator presents the listener (and reader) with a choice: either believe in spite of yourself or deconstruct the story and deconstruct the deeper meaning thereof. The different frames of the story make it possible to choose the former. Eshelman (2008, 1) explains it as follows: "The narrative is constructed in such a way that the viewer has no choice but to transcend his or her own disbelief and accept the performance represented by the film as a kind of aesthetically mediated a priori."

Another important element contributing to the success of the performative double frame is the presence of a dense or "opaque" character or subject, representing what Eshelman (2008, 8) deems "performative subjectivity." Unlike the typically postmodern character-subject which is perpetually destabilised and fragmented by the context outside of the text, the performative subject (characters like Kasper and Schreuder) is constructed to be "dense or opaque" concerning the extra-textual context. "Dense or opaque," as used by Eshelman, can be read as obtuse, slow-witted, and perhaps having autistic traits. Such dense characters have an ambivalent function since, due to their density, they can be cut off from the "normal" social environment due to their "otherness to the extreme" (Murray 2008, xvii). Yet they still can profoundly influence that social environment. Although the ideal is that the society surrounding the character will react positively to their presence and influence, this is unfortunately not always the case according to Eshelman (2008, 8). Due to their singularity and inscrutability, the subject may incur the hostility of their social environment, which is precisely what happens to Karel and Andries.

There are two possible outcomes of the interaction between the dense subject and their social environment: "spontaneously arriving at a common projection together with a potential opponent" (Eshelman 2008, 8), or the social environment can turn violently against the singular subject. The latter corresponds to what happens to the victim stereotype referred to earlier. The former can occur in the form of an "originary [or] reconciliatory scene" (Eshelman 2008, 8). In such a case, the conflict is defused, and the subject has a profound influence on another individual (character) or group of individuals. However, if the situation becomes violent (physically or emotionally), there is the possibility of a scene where the subject is sacrificed, "a sacrificial scene." In such a scene, the subject is eliminated from the frame of the text but also deified in the process. Such deification after elimination results in the subject becoming a focal point of identification and emulation for other characters and/or the reader (Eshelman 2008, 9). This is essentially what happens to Kasper Olwagen and Peter Schreuder. After all the correspondence with his creative writing lecturer, to which she mostly reacted negatively, Kasper disappears without a trace. The lecturer realises only after the student's disappearance that the communication (mostly one-sided) between them was of inestimable value and that he had insight into things she herself has not yet grasped. She begins to follow his example in his absence. In Peter's case, he does not physically disappear, but his strange unapproachable demeanour and obsession with birds and bird sounds, together with his photographs, become aesthetically and ethically inspiring to the Van Niekerk character. Both characters thus transform into a type of divine or metaphysical figure of identification and emulation.

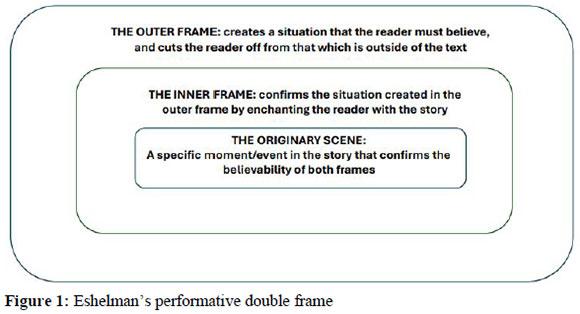

Eshelman's idea of the double frame relates to Derrida's deconstruction of the presumed centre or essence of a work. Eshelman builds on Derrida's explanation (as discussed by Eshelman [2008, 1]) that the frame of a work places the aesthetic value of the artwork in an inseparable relationship with the space or context outside the frame. The frame, once considered an ornamental afterthought, becomes a necessary condition that stands both inside and outside the text (Eshelman 2008, 1-2). According to Derrida's view, the presence of the frame means that the "presumed closure of the work is always already dependent on the context around it, which is itself everything other than a coherent whole." By this line of thinking any claim of unification or closedness in a work of art is futile from the start. Eshelman, however, turns Derrida's idea on its head by proposing a radical new performative empowerment of the frame. Eshelman argues that performatist works can establish a new sense of oneness without succumbing to Derrida's poststructuralist "trap" of framing by radically empowering the frame in a new way, "using a blend of aesthetic and archaic, forcible devices" (Eshelman 2008, 2).

The author of a text containing such framing creates a situation where the text is cut off from the reality outside of it, and where the reader is led, or even forced, to seek meaning only within the text. Performatist works are structured so that the reader or viewer is compelled to adopt a single, obligatory solution to the issues presented in the work. Eshelman (2008, 2) explains:

The author, in other words, imposes a certain solution on us using dogmatic, ritual, or some other coercive means. This has two immediate effects. The coercive frame cuts us off, at least temporarily, from the context around it and forces us back into the work. Once we are inside, we are made to identify with some person, act or situation in a way that is plausible only within the confines of the work as a whole. In this way performatism gets to have its postmetaphysical cake and eat it too.

The reader, however, is very much aware of the effect that this has on them: they are "forced to identify with something implausible or unbelievable within the frame" while still feeling the "coercive force causing this identification to take place [...] intellectually [...] aware of the particularity of the argument at hand." The author is deliberately guiding the reader to identify with something unlikely or unbelievable within the text with the aim to convince the reader "to believe in spite of yourself" (Eshelman 2008, 2).

Eshelman's double frame consists of two "interlocking devices" (Eshelman 2008, 3): an outer frame (or the frame of the artwork or text) and an inner frame, which sometimes involves an origin scene. The outer frame works in such a way that a realistic, ritualistic narrative situation (such as the lecture and inaugural address in "The Swan Whisperer" and "The Friend") is created, temporarily cutting the (sceptical) reader off from the endless open and uncontrollable context outside the frame. The performatist outer frame pushes the reader back into the work to judge all events in the story there, by utilising a strong inner frame that confirms that which the outer frame has posited. A text using a performative double frame usually contains an essential scene or series of events as an inner frame that confirms the artificial logic of the outer frame (Eshelman 2008, 3). Multiple double frames can also be present in a text, as is the case in the short stories in Die sneeuslaper (2010). The fact that this coercive situation takes place in front of legitimately sceptical readers' eyes means that there will always be a certain amount of tension: Whether a work is experienced as a whole with identification and closure, or as "an exercise in endless ironic regress" (Eshelman 2008, 3-4) will be determined by the degree to which the outer and inner frames of the text coincide or not. What is important, however, is that the reader is distinctly aware throughout that the experience of identification or belief is coerced-that it is artificially constructed. The frame thus does not eliminate scepticism and irony but keeps it under control. The reader is expected to negotiate between the aesthetic identification and the constructed manner in which it arose (Eshelman 2008, 2-3). The success of the performatist situation depends on the outcome of the choice that the reader is presented with: Will I choose to believe what the text is presenting to me, or will I stick to my deconstructivist way of reading?

Whereas the outer frame has an arbitrary or dogmatic character that appears to be "imposed" from above, from the position of the author or the authoritative focaliser, the inner frame is based on what Eshelman (2008, 4) calls an "originary scene." Such a scene reduces human action "to what seems to be a very basic or elementary circle of unity with nature and/or with other people" (2008, 4). The originary scene is compelling and represents a type of climax that brings about a turning point in the story. According to Eshelman (2008 4), the originary scene is related to what Eric Gans calls semiotic ostensivity. Gans depicts the origin of language in a hypothetical interaction between two proto-humans engaged in a conflict over some object.15 Instead of one proto-human overpowering the other through violence, one of them gestures towards the object and emits a sound meant to represent it. If the second proto-human accepts this sound as representative of the desired object, the sound becomes "an ostensive sign," and the conflict is averted. Since the sign can avert conflict, the two proto-humans assume that the sign must possess supernatural powers, as they cannot comprehend their involvement in its creation. Gans's point is not that the sign is genuinely of divine origin, but that it can be experienced as such (Eshelman 2008, 4).

Eshelman (2008, 6) regards the ostensive sign and the "originary scene" as fundamental tools "that can help us describe other monist strategies as they cut through the endless regress and irony of postmodern culture and play out new, constructed narratives of origin in contemporary narrative and thematic guises."

In the case of Kasper Olwagen, the parcels he sends represent a series of such origin scenes because they lead the Van Niekerk character to eventually sit by the river and idealise Kasper's literary and philosophical insights. The improbability that a creative writing lecturer would come to such profound new insights about life based on the possibly fictitious experiences of a world-weary student ultimately becomes believable. So much so that the Van Niekerk character herself says she no longer doubts what Kasper has told her. How then can the reader not also believe it?

In the case of Peter Schreuder, the moment when the Van Niekerk character looks at his photos with new eyes functions as such an origin scene: It causes her to see life anew and inspires her to try to understand the strange gibberish Schreuder speaks. Because in that, she believes, lies true meaning.

Conclusion

Characters with what appear to be autistic traits can be seen as an archetype in Van Niekerk's narrative oeuvre in its entirety, and especially in her short stories. Van Niekerk portrays such characters as outsiders and fringe figures who do not fit into the regulated frames of society. At the start of her narrative oeuvre (most notably in Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het from 1992) Van Niekerk depicts these characters as marginal figures who are kept under control, monitored, or expelled from society by other characters, to be cared for in "safe" environments. Their unique vision of the world is not recognised and is easily dismissed as deviant or simple. These characters seem to be depicted as stereotypes in the same vein as Sherlock Holmes and Charlie Gordon, depictions that literary and autism scholars have critiqued fervently (see Loftis 2015). Additionally, from the short stories, it can be inferred that Van Niekerk makes the argument that artists can identify with these types of characters: Artists are also sometimes seen by society as dreamers, timewasters, and idealists who should be kept at arm's-length for fear that their "otherness to the extreme" (Murray 2008, xvii) might become too much to handle.

The process of escaping from cool rationality as an artist and surrendering oneself to sensory and mystical experiences (Van Vuuren 2016, 922) is developed in Van Niekerk's oeuvre into a strong artistic theme. Some of her characters (not only the ones with autistic traits) repeatedly experience the same thing: They become disillusioned by society's pressure to be writers who convey reality in sophisticated, insightful, realistic, and engaged ways. In reaction, they actively choose to transcend that limiting frame and surrender themselves to the earthly, the quiet, the material, and the sensory. In the process, these characters display antisocial, seemingly autistic behaviour that allows them to experience reality in a more purified, sincere, and authentic way. The result is usually one of two possibilities: They are either expelled from society because they behave outside of the norm and become the stereotypical (autistic) victim, or they achieve a type of deified, almost shamanistic status and are admired and imitated by other characters. A certain shift can be seen in Van Niekerk's short stories from the former to the latter. I read this as Van Niekerk confirming Loftis's (2015, 155) argument that literary depictions of autism are increasingly going beyond mere stereotypes. Initially, characters with disabilities (such as Agaat and Lambert) and specifically seemingly autistic traits (such as Karel and Andries) are depicted as helpless, vulnerable, and unable to transcend their limiting surroundings. Their attempts are fruitless, and they end up in similar, or even worse, situations. In her more recent short narratives, however, Van Niekerk paints these characters' imitation-worthy artistic abilities and strengths as sprouting directly from their autistic traits. The hesitant inference of this, it seems, is that there might still be hope for the artist to also have some influence, even if it seems "narcissistically grandiose" (Van Niekerk 2008, 116) for an artist to compare herself to someone who has what seems like transcendental insight.

In Hooked (2020, viii), Rita Felski argues that a reader becomes captivated when they experience a connection or "relation" with a text and when they feel a sense of attachment. I have always wondered what it is about Die sneeuslaper that captivates and engrosses me so much. How does Van Niekerk manage to make me feel, by the end, as if I have gained new insights about life similar to that which the Van Niekerk character experiences? Eshelman's performative double frame offers a good narratological-technical explanation of how this happens. The reader is artificially cut off from the extra-textual reality and led to become completely engrossed in the stories within the text. The orchestrated situation caused by the outer frame, the inner frame, and the origin scene makes the reader a "believer" in the text, despite sceptical and critical conditioning. And the presence of dense characters with autistic traits makes such uncomplicated identification with the text so much more believable. These characters' unique abilities to see the world in unexpected ways affords them this enviable "talent for wonder." By using a performatist double frame, an opaque character with seemingly autistic traits that confirm the fantasticality of the story, and a specific scene where the narrator is led to or decides to believe in spite of themself, the author helps the reader to develop a similar "talent for wonder" (Van Niekerk 1992, 107). Does this cause the reader to view the text with romantic, starry eyes? No, because the reader is constantly aware of the game being played with them. But they have been given the opportunity to see the world through the eyes of someone who represents "otherness to the extreme" (Murray 2008, xvii). Van Niekerk's oeuvre displays an interesting and thought-provoking shift concerning the way that she depicts characters with autistic traits. In the first two stories discussed, the characters are depicted as the stereotypical victims who are cast from society. The fact that the abilities of Kasper Olwagen and Peter Schreuder from Die sneeuslaper are portrayed as strengths and resources, rather than limitations, represents a profound and important shift in Van Niekerk's writerly thinking. This shift is what makes it possible for Van Niekerk to write performatist narratives, which in turn creates the opportunity for earnest enchantment by, and attachment to a literary text.

References

Anon. 2006. "Van Niekerk hou só hart van gode rein." Die Burger, December 14, 20.

Burger, B. 2019. "'Al half dier': objekgeoriënteerde ontologieë, gestremdheidstudies en Siegfried (Willem Anker)." Tydskrif vir Letterkunde 56 (2): 28-37. https://doi.org/10.17159/2309-9070/tvl.v.56i2.4423. [ Links ]

Eshelman, R. 2000-2001. "Performatism, or the End of Postmodernism." Antropoetics: the Journal of Generative Anthropology 11 (2): 1-12. http://anthropoetics.ucla.edu/ap0602/perform/. [ Links ]

Eshelman, R. 2008. Performatism, or the End of Postmodernism. Aurora: Davies Group. [ Links ]

Felski, R. 2015. The Limits of Critique. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226294179.001.0001. [ Links ]

Felski, R. 2020. Hooked. New York: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226729770.001.0001. [ Links ]

Jansen, E., R. De Jong-Goosens, and G. Olivier. 2008. My ma se ma se ma se ma: Zuid-Afrikaanse families in verhalen. Amsterdam: Suid-Afrikaanse Instituut. [ Links ]

Kannemeyer, J. C. 2005. Die Afrikaanse literatuur 1652-2004. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau. [ Links ]

Liming, S. 2020. "Fighting Words." Los Angeles Review of Books, December 14. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/fighting-words/.

Linde, J. L. 2018. "Relasionele performatisme: 'n Metamodernistiese benadering tot die resente werk van Marlene van Niekerk." PhD diss., North-West University. [ Links ]

Loftis, S. F. 2015. Imagining Autism: Fiction and Stereotypes on the Spectrum. Indiana: Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2979/10992.0. [ Links ]

Murray, S. 2008. Representing Autism: Culture, Narrative, Fascination. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. https://doi.org/10.5949/UPO9781846314667. [ Links ]

Olivier, G. 2011. "Die 'einde' van die romantiese kunstenaar? Gedagtes by die interpretasie van Marlene van Niekerk se Agaat (2004)." Stilet 23 (2): 167-186. [ Links ]

Osteen. M. 2008. "Autism and Representation: A Comprehensive Introduction." In Autism and Representation, edited by M. Osteen, 1-47. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. 1977. Sprokkelster. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. 1992. Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. 1994. Triomf Cape Town: Queillerie. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. 2004. Agaat. Cape Town: Tafelberg. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. 2008. "Lambert Benade van Triomf en Agaat Lourier van Grootmoedersdrif. Die kind in die agterkamer as die sjamaan van die familie." In My ma se ma se ma se ma: Zuid-Afrikaanse families in verhalen, edited by E. Jansen, R. De Jong-Goosens, and G. Olivier, 103-117. Amsterdam: Suid-Afrikaanse Instituut. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M. 2010. Die sneeuslaper. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M 2017. Gesant van die mispels: Gedigte by skilderye van Adriaen Coorte ca. 1659-1707. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk. M. 2019. The Snow Sleeper. Translated by Marius Swart. Cape Town: Human and Rousseau. [ Links ]

Van Vuuren, H. 2016. Marlene van Niekerk (1954-) In Perspektief en profiel: 'n Afrikaanse literatuurgeskiedenis, edited by H. P. Van Coller, 919-953. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Vermeulen, T., and R. van den Akker. 2010. "Notes on Metamodernism." Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 2 (1): 5677. https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677. [ Links ]

Viljoen, B. 2012. "Fokalisasie en vertelinstansie in die representasie van gestremdheid in geselekteerde Afrikaanse romans." MA diss., North-West University. http://hdl.handle.net/10394/9236. [ Links ]

1 The title of the collection of short stories Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het (1992) can be translated as "The woman who forgot her binoculars." This collection has not been translated into English. I am using the original Afrikaans and providing my own translations when quoting from the text. Die sneeuslaper (2010) has been translated into English by Marius Swart as The Snow Sleeper (2019). I am using Swart's translation when quoting.

2 Little research exists on characters with disabilities in Afrikaans literature. Two exceptions are Burger (2019) and Viljoen (2012), both regarding Willem Anker's novel Siegfried. No research from a disability studies perspective has been done on Van Niekerk's oeuvre.

3 Arguing that the term "disability" has had a complicated and contested history within the field of disability studies, in his book on autistic writers and characters, Autism and Representation, Osteen highlights the fact that "disability scholarship has ignored cognitive, intellectual, or neurological disabilities, thereby excluding the intellectually disabled" (2008, 3).

4 Since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, according to Loftis (2015, 3).

5 The wide-ranging condition is known as ASD-autism spectrum disorder.

6 Although both Loftis's and Osteen's books focus on English texts from Anglo-American contexts, the argument regarding the empowering shift in the depiction of characters with autistic traits is relevant to Van Niekerk's short stories. This article aims to contribute specifically to the knowledge regarding the depiction of characters with autistic traits in Afrikaans texts.

7 It is interesting to note that in her contribution to the book My ma se ma se ma se ma: Zuid-Afrikaanse families in verhalen (Jansen, De Jong-Goosens, and Olivier 2008) Van Niekerk writes that she could have continued writing about such characters her whole life. This article is proof that she has in fact been doing just that: recreating disabled characters or characters with atypical traits such as Lambert, Agaat, "die agterlike Andries met sy sonnebloem-mistiek [en] die kruppelkind wat meeue voer en name gee" (2008, 105) in a poem from her debut volume of poetry Sprokkelster. This article focuses on the shift that can be seen in Van Niekerk's depiction of such characters.

8 All translations from Van Niekerk's writing are my own, also in the case of academic contributions like this. Swart's translation of The Snow Sleeper is the only existing translated Van Niekerk text used in this article.

9 Knowing that the use of the word "shaman" might be anthropologically insensitive, Van Niekerk (2008, 115) explains that Lambert and Agaat are pseudo-shamans: characters who make subjectively meaningful artworks and perform nightly rituals in unsuccessful attempts to transcend the limitations of their societies, histories, and families. However, unlike true cultural shamans, they do not hold any lasting symbolic, social or cultural influence.

10 Van Niekerk is known to write fictional versions of herself into her texts (see Linde 2018, 200).

11 An interesting link between "Die vriend" and "Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het" is the presence and symbolism of birds. In both "Die vriend" and the title story in the 1992 text, the characters become obsessed with birds. The writer character in "Die vrou wat haar verkyker vergeet het" presents her body to birds as a kind of sacrifice and in an attempt to become one with them in an all-encompassing artwork of nature. In "Die vriend," Peter Schreuder seemingly sacrifices his independence and his use of language to nature and to the birds. In both characters, this obsession might be read in terms of the obsessive behaviour that autistic people sometimes display.

12 Eshelman's ideas should be read within the broader discourse on the supposed "end" of postmodernism and the critical and theoretical possibilities presented within the context of post-postmodernism. Although Eshelman's frame theory might be regarded as negating the insights brought forth by poststructuralism and deconstruction, the way that I believe performatist framing should be read and the way that I am utilising it is within the context of postcritique, new formalism, and ordinary language philosophy.

13 According to Felski (2020, viii), much insight in this debate comes from feminist, queer, and affect scholars. She mentions Toril Moi, Eve Kosofsky Sedgewick, and Silvan Tomkins.

14 Felski herself admits that her ideas in Hooked are perhaps "less exhaustive than [...] suggestive" (2020, 94).

15 This conflict echoes René Girard's mimetic rivalry (Eshelman 2008, 4).