Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae

On-line version ISSN 2412-4265Print version ISSN 1017-0499

Studia Hist. Ecc. vol.50 n.2 Pretoria 2024

https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/16061

ARTICLE

African Accounts of Religious Conversations and Interventions in Mental Healthcare

Daniel Orogun

University of Pretoria arcorogun2@gmail.com https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8642-0724

ABSTRACT

The importance of healthcare has attracted conversations from healthcare professionals, as well as other groups like the United Nations, academic institutions, governments, the private sector, and religious organisations, all contributing to healthcare conversations because healthcare is foundational to human survival. However, there are questions on the quality and gaps of conversations and interventions regarding mental health among religious groups. This is because the quality of healthcare delivery may be rooted in the quality of conversations and interventions. This study explores the quality of mental healthcare (MHC) conversations and interventions in Traditional Religions, Christianity, and Islam in Africa. It interrogates past and recent conversations and interventions within the frameworks of spiritual care (SC) as a form of compassion science, interreligious collaborations, spiritual healings, and allopathic collaborations. Lastly, it places a searchlight on the loopholes of spiritual care in MHC and recommends closure where possible in the pursuit of improved healthcare and well-being in Africa.

Keywords: collaboration; compassion science; conversations; healing; interventions; mental healthcare; spiritual care

Background

The purpose of this article is to present the levels of conversations and interventions in mental healthcare within the religious groups in Africa and to interrogate how robust are these conversations and interventions in terms of bridging the gap between the low supply and high demand of healthcare support. The purpose assumes that the more robust mental healthcare conversations are, the better the quality of interventions that will come from religious groups. It is on this notion that a brief background is presented ahead of the accounts of conversations and interventions.

It is a popular notion that everyone desires to be happy to achieve self-actualisation as the ultimate goal of life. However, it is subject to factors underscored by Maslow's hierarchy of needs, which include shelter, food and water, sufficient rest, and overall health, among others (McLeod 2018, 1-16). Although immortality is not guaranteed in human existence, the need for constant health maintenance while it lasts is imperative. One crucial issue that impacts negatively on sustainable happiness is the mental health challenge. Although Healthcare professionals are continuously trained to provide services to victims, the current global demand for mental healthcare (MHC) outweighs the supply. The fact sheet of the World Health Organisation - WHO (2019) reveals that 300 million people, irrespective of region, culture, age, gender, religion, race, and economic status, experience mental illness with possible escalation to depression and disability. WHO (2023) submits that more than 75% of Africans suffering from trauma or stress do not receive treatment (cf. Naylor et al. 2012). About 29.19 million people (9% of 322 million) suffer from depression, with over 7 million in Nigeria (3.9% of 322 million). The estimation of Esan and Esan (2016) places the lifetime prevalence of depressive disorders from 3.3% to 9.8%. Likewise, the assessment of WHO (2023) indicates that about 5 million annual deaths are caused by trauma and related mental health challenges (MHCS) in low- and middle-income countries like South Africa. Mayosi et al. (2012, 380) add that such MHCS remain one of three of South Africa's top public health crises. Between 2000 and 2015, Africa's population increased by 49%, yet mental and substance use disorders increased by 52% and 17.9 million lives were lost to disability because of MHCS (WHO 2019). Similarly, depression is the most prevalent mental illness in the world, with about 100 million victims in Africa, out of which 66 million are women (Mayberry 2021; cf. Elias et al. 2021, 206).

The background above shows buckets of challenges beyond the capacity of healthcare professionals in Africa. While evidence shows the long-standing involvement of African governments in MHC, public domain literature shows less robust conversations and interventions besides divine healing and miracles from religious groups. For example, 22 years ago, the Parliament of South Africa (2002) was involved in policy development on MHC (cf. Romero-Daza 2002, 174-176). Whereas supernatural healing dominates the conversations about MHC among religious institutions. Currently, increasing demand for MHC has led to what the WHO calls "Collaborative Interventions" (WHO, 2022). This call raises questions regarding the role of spiritual care (SC) in collaborative intervention. If the religious bodies do not participate in collaborative intervention, what are the implications and gaps created? If they do, how much of an impact has it had on the field of MHC? Are there historical accounts and loopholes to that effect? What recommendations are available to cover such loopholes? To answer these questions, conceptual clarifications and links will be presented. Subsequently, African historical accounts of conversations and interventions in African Traditions, Christianity and Islam will be presented and interrogated. The outcome will determine the recommendations for possible closure of discovered loopholes and activation of collaborations.

Conceptual Clarifications and the Links

Mental Health

The American Psychological Association (APA) defines mental health (MH) as a "state of mind characterised by emotional well-being, good behavioural adjustment, relative freedom from anxiety and disabling symptoms, and a capacity to establish constructive relationships and cope with the ordinary demands and stresses of life" (Review of Mental Health 2020). The closest synonyms for MH include flourishing and normality ((Review of Mental Health 2020). WHO sustains that a good state of mental well-being helps people to cope with the stresses of life, realise their abilities, learn well, work well, and contribute to their community. Besides the fact that MH is a human right for all, WHO believes that MH is a tripartite value condition in the sense that it is crucial to personal, community and socio-economic development (WHO 2022). Related conditions in MH include mental disorders, psychosocial disabilities, distress, impairment in functioning and risk of self-harm, among others. People with such conditions, in some cases, experience lower mental well-being (Review of Mental Healthcare 2024; WHO, 2022; (Review of Mental Health 2020).

Mental Healthcare

The Collins English Dictionary calls mental healthcare (MHC) a "Devoted Service" and a category of healthcare service and delivery provided by several fields involved in psychological assessment and intervention (Review of Mental Healthcare 2024). Such care includes but is not limited to psychological screening and testing, psychotherapy and family therapy, social work and neuropsychological rehabilitation (Review of Mental Healthcare 2020). Concomitantly, the phrase "Devoted Service" introduced by Collins English Dictionary sounds related to service to humanity, a culture across religions.

Compassion Science

One of the shortest definitions was given by Cole-King and Gilbert (2011, 29), who claim that compassion science (CS) is not only a sensitivity to the distress of others but also a commitment to try and do something about it. Thus, compassion requires action (Cole-King and Gilbert 2011, 29-30). Mathers claims such action is not "an optional extra" (2016, 525), deployable when there is sufficient time and energy, nor is it just instrumental in achieving another purpose; rather, it should be central to our engagement with others. Additionally, compassionate service can be part of what Brown and Brown called "prosocial psychology" (2015,1). From the study of origins, Gilbert (2019, 108) reports that CS is a prosocial behaviour which evolved from mammalian caregiving of offspring (cf. Brown and Brown 2015). How mammalian infants are cared for by their parents with rapt attention to address their distress and needs, take actions to relieve such distress, prevent future distress and suffering, support growth, and prepare offspring for independent living remain the perfect example of compassion for caregivers (Gilbert 2019, 108). With over 30 years of the presence of prosocial psychology, as claimed by Gilbert (2019, 108), and despite the record of the pioneering work of epidemiology of compassion by Levin (2000), among others, such positive epidemiology remains underdeveloped. Correspondingly, Addiss et al. (2022, 2) suggest that little attention is given to the epidemiology of compassion. Regardless, scientific evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of compassion at the individual level but is underdeveloped at organisational and population levels (Addiss et al. 2022, 2).

Spiritual Care

It means ways in which attention is paid to the spiritual dimensions of life and meeting the spiritual and emotional needs of individuals or groups. It includes presence, conversations, rituals, ceremonies, prayers, and the sharing of sacred texts and resources (Spiritual Care Australia, n.d). A fundamental question to ask is how spiritual care (SC) finds expression in MHC through compassion science (CS). First, religiosity and spirituality as foundations for SC were long associated with the epidemiology of compassion. In the research of Addiss et al. (2022, 20), 13 spirituality and religion tests were conducted, and the result showed that 10 (76.9%) out of 13 tests imply an association with compassion. Correspondingly, Armstrong (2009) argues that compassion is popular across religions and spiritual traditions. While it may not be a core scientific activity, research reveals that it increases the quality of life of patients. For example, the report of Balboni (2011, 5383-91) notes that patients with limited SC experience more worries, anxiety, shortness of breath, and pain with higher chances of hospitalisation and death at intensive care units instead of at home. Such a scenario puts patients and relatives in more emotional pain and financial costs. Notwithstanding the value of SC, Addiss et al. (2022, 20) suggest that religion can still deflate compassion with issues like division, cruel religious dogma, and the withholding of compassion for in-groups through actions of injustice, discrimination, etc.

The Links

The clarifications above show a few nomenclatures connecting mental healthcare (MHC), spiritual care (SC) and compassion science (CS). One of the synonyms used by APA Dictionary (2018) for mental health is "flourishing". This word is familiar to Christianity, as recorded in Psalm 92: 12-14, where the Psalmist discusses flourishing like a palm tree and bearing fruit in old age. By implication, it seems the Psalmist is connecting flourishing to well-being and good old age, just as flourishing is used in the APA Dictionary of Psychology to depict mental wellness. Thus, "flourishing" links spirituality and psychology. Compassion is also a popular nomenclature in the three religions under consideration. Bible records indicate the centrality of compassion in healing (Matt 14, 14-21; Mk. 1, 41). Islamic literature considers compassion in works and actions (Quran 2, 83; 2, 195). In African moral and religious traditions, Ubuntu, Ujamaa and Philosophical Consciencism all support compassion in African communitarian society (Orogun and Pillay 2021, 5-6; Orogun 2020, 57-101). As mentioned earlier, the Collins English Dictionary calls MHC a "Devoted Service" (Review of Mental Healthcare 2024), while Levin (2000) and Gilbert (2019, 108) used the phrase epidemiology of compassion to depict such devoted service. By inference, there is a link between religion (spiritual care) and a psychological view of compassion in MHC. Likewise, the word "service" is central to the religious responsibility in African communities and beyond. Thus, the Collins Dictionary supports both religious and psychological concepts of compassion in MHC.

The Conversations and Interventions

The conversations and interventions will be presented under regions and countries with African Traditional Religions (ATR), Islam, and Christianity in view.

Southern Africa

Zimbabwe

In the previous section, reference was made to the assertion of Addiss et al. (2022, 20) with the claim that religion can deflate compassion with many social issues and religious dogma. The conversation in Zimbabwe is a testament to such a possibility. Mpofu et al. (2011, 551-66), in the case of the Apostolic Faith Church, report the impact of church socio-spiritual dogma on the mental well-being of congregants. Such dogmatic practices include rules restricting the sexual intimacy of couples, breastfeeding mothers, the rule of husbands' consent as the only condition of admittance of women into the church family, and the restriction of marriage only between church members. Forceful compliance with these rules easily affects the mental wellness of members. Mpofu et al. (2011) summarise that some African churches have tendencies to increase the mental crises among members because of existing behavioural laws or structures which tamper with the freedom and rights of members, especially women, youth, and children. Thus, denominational rules could potentially harm congregants' mental well-being. This queries the capacity of some African churches to provide MHC support to congregations or collaborate with allopathic service providers to improve MHC in communities.

Malawi and Mozambique

Crabb et al. (2012, 3) report that the majority of respondents in their research from both mental health and non-mental health clinics and hospitals blame mental illness on substance misuse and spiritual causes like spirit possession and God's punishment. 82.8% of respondents claim that mental illness is caused by spirit possession, 21.9% claim God's punishment remains the cause, and 43% think poverty causes mental illness in Malawi. Using their data outcome, Crabb et al. (2012, 4) assert that such spiritual belief may explain why many mental illness issues in Sub-Saharan Africa are treated punitively by traditional and faith healers. This assertion may be correct because, in Western traditions, the mind and body are considered distinct entities, whereas in Malawi, spiritual possession is believed to influence the brain directly (Crabb et al. 2012, 4). Generally, there is a perception that causes and interventions are spiritual as people strongly believe more in traditional and faith healers.

As a sequel to the spiritual care subscription in MHC, Schumaker et al. (2007) provide a historical account of how African Presbyterian church leaders and Scottish missionaries negotiated the acceptability of the practices of African healers in the northern part of Malawi. The account provides how Malawian independent churches adopted healing practices as central to ministry. The adoption further influenced the emergence of Mozambican prophetic healing around 1993 as returning refugees with healing experiences in exile imported the practices from Malawi (Schumaker, Jeater and Luedke 2007, 709). By the 20th century, in an attempt at establishing medical pluralism, the Presbytery formed a "Charms and Superstitions Committee" made up of seven African church elders and three European mission doctors. According to Schumaker et al. (2007, 710), the Scottish missionaries wanted African Christian communities to wholly depend on a mission medicine built on scientific foundations. Contrarily, African church leaders took the flexible approach, thereby allowing congregations the right to use African medicine.

South Africa

Research focusing on 6 Muslim healers in Johannesburg conducted by Ally and Laher (2007, 45-56) shows that Islamic faith healers concurred with spiritual and biological causes of mental illness. However, they can differentiate the specific causes and then advise on treatment. They agree on the relevance of collaboration between faith and allopathic healing. The faith healing treatments were based on religious doctrine (Ally and Laher 2007, 54).

In Christianity, coping-healing churches are of two types: the African Independent churches (AICs) and the Charismatic-Pentecostal (Bate 2001,4). These healers provide services through prayers either in interpersonal or group encounters (Bate 2001, 5). Healers' focus on confession and forgiveness of sin indicates the impression that ill health has a spiritual origin. In addition, Sikosana (as quoted in Bate 2001, 6) asserts that the prophetic or prayer healers (umthandazi; mofodisi, umprofethi) leverage the skills of African traditional healers (isangoma, ngaka, inyanga) and the communities with health challenges including mental illness heavily depend on and subscribe to AICs healers (Bate 2001, 6). However, Kruger (2012) notes that in Afrikaans-speaking churches, the clergies mainly adopted a biopsychosocial-spiritual approach to mental illness, an approach accessed only by the middle class. Conversely, Nhlumayo (2021, 29) argues that biopsychosocial models do not neatly overlap with cultural and spiritual beliefs about mental illness. Consequently, most South Africans subscribe to accessible faith healers through churches (cf. Nhlumayo 2021, 28).

In ATR, Sorsdahl et al. (2023, 6) discuss an investigation of mental health patients seeking help in allopathic medicine. Outcomes reveal that about 17% made first contact with a traditional healer, while 26% met a religious advisor. Such outcomes have also been reported in South Africa (Sorsdahl et al. 2023, 5-6). The research of Bosire et al. (2022, 1172-85) in Soweto is a good example.

Southern Africa in General

Mabvurira, Makhubele, and Shirindi (2015, 425-434) provide a research account of Johane Masowe Chishanu (JMC), domiciled in Zimbabwe and South Africa. Collecting data from 15 prophets, six assistant prophets, and nine chronically ill people who sought church assistance in Buhera District in Zimbabwe and Seshego in Limpopo, South Africa. The result indicates that, among others, avenging spirits, witchcraft, and punishment are the causes of illnesses. JMC uses healing instruments like the leaves of the hissing tree, the prophetic action of burying the problem, and singing and pointing to the east (Mabvurira et al. 2015, 425). Other instruments used for MHC include water, leaves, and clothes, as in African Traditional Religions (Mabvurira et al. 2015, 432). JMC's syncretic approach to MHC covers countries like Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, Angola, Tanzania, Mozambique, Malawi, and Zambia. Meanwhile, ZCC is said to be akin to JMC in such healing practices (Mabvurira et al. 2015, 426). The spreading of mental healing practices in JMC and ZCC implies a wide coverage of spiritual healing of mental illness in Africa. Correspondingly, AICs are all over Africa, as confirmed by Olawo (2021, 54) and Ludwig (1999, 125). They are regarded as healing centres, and according to Msomi (1967, 66), every Sunday service in AICs is incomplete without a healing prayer (cf. Mashabela 2023, 1369).

West Africa

Ghana

Among all forms of MHC, Salifu, Kpobi and Sarfo (2016, 985) assert that over 70-80% of patients subscribe to traditional and spiritual treatments in Ghana. Correspondingly, there are over 45,000 traditional healers and church facilities for treatments (WHO, 2007). These options are not based on the best approach but on the lack of better alternatives, the high cost of Medicare, and the spiritual perception of mental illness, which is not unconnected to the assertion that religion permeates all aspects of the lives of Africans, including their mental well-being (Mbiti 1985; cf. Salifu et al. 2016, 985986). Faith healing is also certified among the neo-prophetic groups by the use of standing committees to investigate the background of patients, testimonies by sick persons' relatives and showcasing of sick persons confirmed medical reports to congregants. (Kpobi et.al 2018, 1-12).

Nigeria

In Benue, 100 people were interviewed by Ishor et al. (2022, 365-75) on their experiences and opinions about consultation, effectiveness, and challenges of spiritual healing practices. Results reveal that patients visit spiritual healers as their first port for treatment and prevention. Regardless of high subscriptions, people face challenges like stigmatisation and victimisation in seeking MHC and fake spiritual healers are parading around and defrauding patients. In Ibadan, after the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia (IPSS) discovered that those diagnosed as schizophrenic recovered better than similarly diagnosed people in 8 other countries (WHO 1979), international psychiatric interest shifted to traditional treatment in Africa. Regardless of the non-acceptability by Western psychiatrists, the efficacy of African native healers has been widely attested to (Odejide et al. 1978, 167; Collis 1966). The successes of prophetic healers have been recorded by Lehman (1972), while Lateef (1973) discussed the successes of Muslim healers: the marabout.

In Michael's research in 2022, using the data of over 250 sick clients in African healing shrines, over 50 practitioners in ethnomedical shrines, doctors and nurses, church workers and Christian healers in Nigeria and Ghana, respectively, it was obvious that networks of referrals between African healing shrines, hospitals, and Christian healing and prayer exist (Michael 2022, 1). However, for mental illness, most African healers rarely refer their patients to Western medicine, referring to it as a waste of time because it is unable to cure mentally ill Patients (Michael 2022, 10). More interestingly, Esan et al. (2018, 395-403) researched the profile, practices and distribution of faith and traditional healers as members of the Alternative Mental Health service providers, with 205 in Ghana, 406 in Kenya and 82 in Nigeria. Results show that over 70% of the healers treat both physical and mental illnesses. These alternative MHC practitioners undergo long years of training and apprenticeship, using a combination of herbs, divination, and rituals to treat mental disorders. A long duration of training, up to 10 years under older healers, was commonly reported by healers. With the application of restraints in some cases, they provide MHC. However, to fully integrate them into collaborative healthcare with the public health system, Esan et al. (2018, 400) advocate the need to address harmful treatment practices.

East Africa

Burundi

In the account of Irankundu et al. (2017, 68), ATR and Christianity are at the centre of the MHC conversation. Before the arrival of missionaries in the 19th century, a traditional practice called kubandwa was used to treat mental illness, a system appreciated by the patients and communities. The documentary of Ngabo (2010) shows that the arrival of the missionaries led to the gradual disappearance of kubandwa as they classified mental illness as demonic possession caused by sin. While ATR created acceptance, compassion and care for patients, Christianity came with stigmatisation and blame. Although prayers were often offered to attract forgiveness of sin and purification, no robust account of prayers provided healing like kubandwa. Since Kubandwa faded away, there has been no historical evidence of collaboration between the allopathic and religious groups; most Burundians believed mental illness was spiritual at the time. (Irankunda et al. 2017, 68).

Tanzania and Zanzibar

Research conducted to investigate the prevalence of mental disorders among 178 patients attending traditional healing centres in Dar El Salaam shows that 48% of patients suffering from mental disorders are at traditional healing centres (Humaida and Kegour 2021, 5; Ngoma et al. 2003, 349-55). Furthermore, a study in Zanzibar shows that Patients reported attending traditional healers more readily than biomedical clinics for reasons like accessibility, affordability and preference for the traditional healers' treatments. MHC reviews and Zanzibar health ministry reports indicate that visiting traditional healers before allopathic services increase in line with the population growth and scarcity of medication in the public sector (Jenkins et al. 2011). According to Solera-Deuchar et al. (2022), in 2008, the Zanzibar Ministry of Health released a Traditional and Alternative Medicine Policy to (1) Reduce the risk of harmful practices, (2) Enable a closer relationship with mainstream practitioners and (3) Recognise Traditional Medicine's contributions rather than see it as a threat.1 However, the role of traditional and alternative medicine in MHC is not addressed in the policy. This is a grey area that needs attention not only in Zanzibar but all of Africa (Solera-Deuchar et al. 2020, 1 -10).

Ethiopia

The situation in Ethiopia is a perfect example of high demand but a very low supply of MHC. Alem et al. (2009, 646-54) report a 90% gap between the demand and supply of healthcare for schizophrenia. Additionally, specialist human and material resources are scarce, healthcare policy is poor, and community awareness is very low (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health, 2012). Consequently, Ethiopians with mental illness heavily rely on family support, traditional healers, and holy water sites (Selamu et al. 2015, 2).

Uganda

The conversations in Uganda suggest the existence of three kinds of mental healing systems: allopathic, traditional, and religious. Records also exist on the emergence and existence of Islamic healings beginning from the 19th to 20th century in Uganda and other East African nations, as the research of Ihsan (2000) suggests that religious leaders are beckoned to help with mental health problems. However, Teuton, Dowrick, and Bentall (2007, 1261) assert that rarely have these religious protocols been the subject of research. With all these healing systems, Teuton et al. (2007, 1260-1273) suggest there is no collaboration among the three systems. While traditional healers tolerate evidence-based Western medicine, there is no reciprocity. Additionally, both the African Traditional healers and religious healers from evangelical settings think their healing protocols are incompatible.

North Africa

Egypt

In the medieval account of Al-Maqrizi in Islam and Campbell (2012, 232), a man in Cairo who was afflicted with madness (Junun) became popular for acting as the Sultan. Rather than being helped, he was whipped, had his tongue cut out and imprisoned. Another mentally ill fellow in Cairo who escaped from the hospital and declared himself a prophet was punished. These inhuman treatments from overzealous religious adherents and leaders stigmatise and take away the humanity of patients. Conversely, other Islamic folks believe that mental illness has supernatural origins. Thus, they sought charms and amulets to ward off Jinn, the evil eye and black magic responsible. In recent findings of Assad et al. (2015, 583-90), the impact of traditional healing in curing mental illness is huge. The outcome shows that 40.8% of respondents sought traditional healers only, 62.2% met with traditional healers before seeking psychiatric services and 37.8% after. Islam and Campbell (2012, 232) further notes that even holy men (shaykhs) performed exorcisms on the mentally ill (cf. Shoshan 2003, 329-40; Dols 1987, 1-14). Also, history shows that some prominent Islamic scholars, including Ishaq ibn Imran and Ibn Sina, wrote on three groups of mental illnesses, including canine madness, lycanthropy and phrenitis (Dols 1987, 5). Ibn Sina particularly rejected that mental illness has supernatural origins. These scholars believed in Islamic medicine for MHC (Islam and Campbell 2012, 232). Summarily, there are three points in these accounts. First, there were issues of stigma and ill-treatment of patients. Second, there are syncretistic practices involving the combination of charms, amulets and black magic to ward off spirits responsible for mental illness. Third, there are subscriptions to alternative medical healthcare services as some Islamic scholars reject the supernatural origins of mental illness and rather embrace Islamic medicine. Such Islamic medicine, which embraces herbs and plants alongside Islamic counselling in Egypt, may not be unconnected to Islamic Western practices in the United Kingdom, a system intrinsically rooted in Islamic teachings derived from Tibb Medicine, which is the Medicine of the last prophet (Maynard 2022, 266 and 281).

Sudan

Humaida and Kegour submit that "Sudanese general traditional medicine, plants and herbs are intensively used in curing different diseases and ailments, specific traditional medicine on contrast, can also be divided into two separate entities: Religious healing, which based on Islamic culture; uses the Holy Quran and Prophetic tradition; Non-religious healing, which is based on African culture; believes in secular practices such as black magic and Zar" (2021, 3). Humaida and Kegour agree no less with this hybridity of treatment when they further explain that religious healers in traditional and religious centres in Sudan apply techniques and methods for healing and treatment of mental illness; these include reading the Quran on the patient, drinking Islamic healing inscription papers soaked in water, wearing amulets and fumigation (2021, 3).

Loopholes

Many loopholes can be inferred from the historical accounts above. Therefore, the author claims no absolute knowledge of all possible loopholes, as only nine points will be discussed below.

First, the historical accounts show that religious interventions and results are immeasurable. Besides using medical reports to ascertain the reality of spiritual healing, most accounts do not show a model for measuring the efficacy and reliability of spiritual intervention in MHC.

Second, there is a tradition of tension. Throughout the accounts, disagreement on the inter-healing system persists with a lack of mutual respect. Specifically, Osafa (2016) asserts there is a 'tradition of tension' between religion and scientific inquiry. Such tension is linked to the history of colonialism, which has thwarted efforts to trust and reconcile these camps.

Third, the accounts show the emergence of fraudulent healers. As presented earlier by Ishor et al. (2022, 365-75), the gap between the high demands and low supply of MHC allows the infiltration of fraudulent spiritualists who have commercialised spiritual and traditional healing, thereby plundering vulnerable patients across Africa.

Fourth, it is clear in the accounts that religious extremism is frustrating MHC collaborations. One common denominator in the conversations is a lack of flexibility on all sides, allopathic practitioners denigrating the ATR healers, Christians disregarding traditional methods of MHC healing, or vice-versa.

Fifth, the risk of harmful practices is evident. Understandably, spiritual healing is not scientific, but that is not a licence for harmful practices, including drinking and exposing patients to harmful substances and concoctions in the name of healing remedy.

Sixth, there is a lack of or poor Government policies on religious treatment of mental illness. Many alternative medicine policies rarely outline the roles of spiritual care. The account of Zanzibar provided above is an example similar to South Africa, where the role of healthcare chaplains is not stated or clear in the healthcare policy (see Orogun 2023, 25).

Seventh, the accounts reveal a lack of social support. The conversations reflect no social causes except in Malawi, where mental illness was attributed to poverty. Beyond spiritual causes, mental illness may be caused by socio-psychological issues like poor awareness, stigma, blame, abuse, violence, child marriage, poverty stress, marriage crises, and inhuman religious dogmas (see Salifu et al. 2016, 985).

Eighth, the theology of healing gaps is obvious in the accounts. Besides conversations of the spiritual origins of mental illness and apprenticeship of spiritual healers, rarely are discussions on the theology of healing applicable. It can then be inferred that poor theological paradigm undergirds the operations of spiritual healers, especially in the Christian faith. This is where theological education needs to come in.

Lastly, there is a lack of compassion science conversations in spiritual interventions. This could be the reason for some church rules and dogma meted out to patients and congregants. With compassion, there will be avoidance of religious and socially harmful practices that can trigger or increase mental illness in patients and congregants.

Conclusion

The accounts presented so far show that conversations and interventions in mental health are carried out across Africa, and sensitivity to mental healthcare spreads across the three popular religions in Africa: Traditional Religion, Christianity, and Islam. Likewise, points of praise for Afrocentric healing for patients emerged in the conversations and interventions. The nature and advantages of the religious conversations and interventions include the fact that (1) Religious interventions are spiritual, hybrid or syncretic, controversial (sometimes) and collaborative in other cases. (2) Religious interventions are popular, appreciable alternatives, acceptable, accessible, and affordable enough to bridge the demand and supply gap and address MHC hopelessness in African communities. However, the accounts reveal loopholes that need attention to improve mental healthcare interventions.

Recommendations

The loopholes discussed above indicate the need for recommendations to improve the spiritual approach to MHC in Africa. A few are provided below, but there can be more.

1) Flexibility for collaborations: The spiritual care dimension should not be a stand-alone MHC system. Most accounts discussed earlier pointed to poor inter-religious and spiritual versus scientific collaborations. To achieve collaboration, each group should be flexible towards others and stay focused on the overall goal: to serve patients, families, and communities. Sometimes, placing organisational interests above patients and community interests defeats collaborative efforts. Flexibility will address loopholes 2 and 4.

2) Mainstreaming compassion science in spiritual healing practices: Poor social support and religious dogma triggering mental illness, among others, show a lack of compassionate approach. The conceptual clarifications section already linked SC, MHC, and CS. Thus, deploying CS will resolve loopholes 5,7 and 9.

3) Spiritual care regulatory policies: The impact of some loopholes will continue without rules of engagement. Individual groups and government policy formation will naturally address loopholes 1,2,3,5 and 6

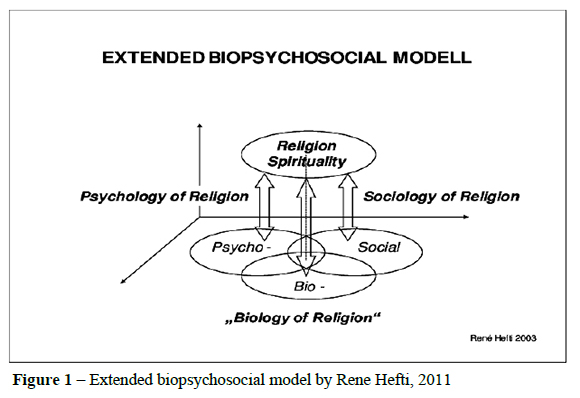

4) Using the extended biopsychosocial model: For collaborations and improved MHC, adoption of Hefti's "Extended biopsychosocial model", as seen in Figure 1 below, is highly recommended for religious groups. It is an extension of the bio-psychosocial model of MHC, of which religion and spirituality now constitute the fourth dimension (Hefti 2011, 611-627). It allows the integration of pharmacotherapeutic, psychotherapeutic, sociotherapeutic and spiritual elements, as spirituality is associated with decreased levels of depression, lower levels of general anxiety, positive outcomes in coping with anxiety, higher levels of recovery from substance abuse, better-coping methods and easy reintegration of patients into their families. (cf. Pardini et al. 2000, 347-354). This recommendation addresses loopholes 2, 4 and 7.

5) Imperativeness of Education: The final recommendation remains the need for faith and traditional healing organisations to embrace theological pieces of training that speak to healing and juxtapose it with basic medical hygiene training. Perhaps this will attract more acceptance by the allopathic community.

References

Addiss, D. G., A. Richards, S. Adiabu, E. Horwath, S. Leruth, A. L. Graham, and H. Buesseler. 2022. "Epidemiology of Compassion: A Literature Review." Frontiers in Psychology 13 (November). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992705. [ Links ]

Alem, A., D. Kebede, A. Fekadu, T. Shibre, D. Fekadu, T. Beyero, G. Medhin, A. Negash, and G. Kullgren. 2009. "Clinical Course and Outcome of Schizophrenia in a Predominantly Treatment-Naive Cohort in Rural Ethiopia." Schizophrenia Bulletin 35 (3): 646-654. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn029. [ Links ]

Ally, Y., and S. Laher. 2007. "South African Muslim Faith Healers Perceptions of Mental Illness: Understanding, Aetiology and Treatment." Journal of Religion and Health 47 (1): 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-007-9133-2. [ Links ]

Armstrong, K. 2010. The case for God. Vintage Canada. [ Links ]

Assad, T., T. Okasha, H. Ramy, T. Goueli, H. El-Shinnawy, M.Nasr, H. Fathy, D. Enaba, D. Ibrahim, M. Elhabiby, N. Mohsen, S. Khalil, M. Fekry, N. Zaki, H. Hamed, H. Azzam, M. A. Meguid, M. A. Rabie, M. Sultan, S. Elghoneimy, O. Refaat, D. Nader, D. Elserafi, M. Elmissiry, and I. Shorab. 2015. "Role of Traditional Healers in the Pathway to Care of Patients with Bipolar Disorder in Egypt." International Journal of Social Psychiatry 61 (6): 583-590. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014565799. [ Links ]

Balboni, T., M. Balboni, M. E. Paulk, A.Phelps, A. Wright, J. Peteet, S. Block, C. Lathan, T.Van der Weele, and H. Prigerson. 2011. "Support of Cancer Patients' Spiritual Needs and Associations with Medical Care Costs at the End of Life." Cancer 117 (23): 5383-5391. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26221. [ Links ]

Bate, S. 2001. "An Interdisciplinary Approach to Understanding and Assessing Religious Healing in South African Christianity." Oblates Of Mary Immaculate In Southern Africa. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://omi.org.za/scbate/interdisciplinaryappraoch.pdf. [ Links ]

Brown, S. L., and R. M. Brown. 2015. "Connecting Prosocial Behavior to Improved Physical Health: Contributions from the Neurobiology of Parenting." Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 55 (August): 1 -17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.004. [ Links ]

Cole-King A., and G. Paul. 2011. "Compassionate Care: The Theory and the Reality." Journal of Holistic Healthcare 8 (3): 29-37. [ Links ]

Collis, R. J. M. 1966. "Physical Health and Psychiatric Disorder in Nigeria." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 56 (4): 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/1006108. [ Links ]

Crabb, J., R. C. Stewart, D. Kokota, N. Masson, S. Chabunya, and R. Krishnadas. 2012. "Attitudes towards Mental Illness in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional Survey." BMC Public Health 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-541. [ Links ]

Dols, M. W. 1987. "Insanity and Its Treatment in Islamic Society." Medical History 31 (1): 114. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025727300046287. [ Links ]

Elias, L., A. Singh, and R. Burgess. 2021. "In Search of 'Community': A Critical Review of Community Mental Health Services for Women in African Settings." Health Policy andPlanning 36 (2): 205-217. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa140 [ Links ]

Esan, O., J. Appiah-Poku, C. Othieno, L. Kola, B. Harris, G. Nortje, V. Makanjuola, B. Oladeji, L. Price, S. Seedat, and O. Gureje. 2018. "A Survey of Traditional and Faith Healers Providing Mental Health Care in Three Sub-Saharan African Countries." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 54 (3): 395-403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1630-y. [ Links ]

Esan, O., and A. Esan. 2015. "Epidemiology and Burden of Bipolar Disorder in Africa: A Systematic Review of Data from Africa." Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 51 (1): 93-100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1091-5. [ Links ]

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. 2012. National Mental Health Strategy 2012- 2015. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Health. [ Links ]

Gilbert, P. 2019. "Explorations into the Nature and Function of Compassion." Current Opinion in Psychology 28 (August): 108-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.002. [ Links ]

Hefti, R. 2011. "Integrating Religion and Spirituality into Mental Health Care, Psychiatry and Psychotherapy." Religions 2 (4): 611-627. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2040611. [ Links ]

Humaida I. A. I. and A. B. Kegour. 2021. "Beliefs and Attitudes of Mental Illness Patients towards Religious Healers in Khartoum." SunText Review of Neuroscience and Psychology 2 (3): 134. https://suntextreviews.org/uploads/journals/pdfs/1639734798.pdf [ Links ]

Ihsan A.-I. 2000. Al-Junün: Mental Illness in the Islamic World. Madison, Conn.: International Universities Press. [ Links ]

Irankunda, P., L. Heatherington, and J. Fitts. 2017. "Local Terms and Understandings of Mental Health Problems in Burundi." TransculturalPsychiatry 54 (1): 66-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461516689004. [ Links ]

Ishor, G., D. Iorkosu, and T. Samuel. 2022. "Spiritual Healing as an Alternative Health Care Delivery in Benue State." International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development 6: 365-375. https://www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd33616.pdf. [ Links ]

Islam, F., and R. A. Campbell. 2012. "'Satan Has Afflicted Me!' Jinn-Possession and Mental Illness in the Qur'an." Journal of Religion and Health 53 (1): 229-243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9626-5. [ Links ]

Jenkins, R., M. Mussa, S. A. Haji, M. S. Haji, A. Salim, S.Suleiman, A. S. Riyami, A. Wakil, and J. Mbatia. 2011. "Developing and Implementing Mental Health Policy in Zanzibar, a Low Income Country off the Coast of East Africa." International Journal of Mental Health Systems 5 (1): 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-4458-5-6. [ Links ]

Kpobi, L. N. A., and L. Swartz. 2018. "'The Threads in His Mind Have Torn': Conceptualization and Treatment of Mental Disorders by Neo-Prophetic Christian Healers in Accra, Ghana." International Journal of Mental Health Systems 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-018-0222-2. [ Links ]

Kruger, Q. 2012. "Review of Treatment of Mental Health Illness by Afrikaans-Speaking Church Leaders in Polokwane Limpopo Province." PhD Thesis, University of Limpopo. [ Links ]

Lateef, N. V. 1973. "Diverse Capacities of the Marabout." Psychopathologie Africaine 9 (1): 111-129. [ Links ]

Leavey, G., K.Loewenthal, and M. King. 2017. "Pastoral Care of Mental Illness and the Accommodation of African Christian Beliefs and Practices by UK Clergy." Transcultural Psychiatry 54 (1): 86-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461516689016. [ Links ]

Lehman, J.-P. 1972. "La Fonction Therapeutique du Discours Prophetique (Prophetes- Guerrisseurs deCote d'lvoire)." Psychopathologic Africaine 8: 355-382. [ Links ]

Levin, J. 2000. "A Prolegomenon to an Epidemiology of Love: Theory, Measurement, and Health Outcomes." Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 19 (1): 117-136. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.117. [ Links ]

Ludwig, G. D. 1999. Order Restored: A Biblical Interpretation of Health Medicine and Healing. Missouri: Concordia Academic Press, 1999. [ Links ]

Mabvurira, V., J. C. Makhubele, and L. Shirindi. 2015. "Healing Practices in Johane Masowe Chishanu Church: Toward Afrocentric Social Work with African Initiated Church Communities." Studies on Ethno-Medicine 9 (3): 425-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/09735070.2015.11905461. [ Links ]

Mashabela, J. K. 2023. "Africa Independent Churches as Amabandla Omoya and Syncretism in South Africa." Religions 14 (11): 1369-1369. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14111369. [ Links ]

Mathers, N. 2016. "Compassion and the Science of Kindness: Harvard Davis Lecture 2015." British Journal of General Practice 66 (648): e525-e527. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16x686041. [ Links ]

Maynard, S. A. 2022. "12 Addressing Mental Health Through Islamic Counselling: A Faith- Based Therapeutic Intervention." Edinburgh University Press EBooks, December, 256 286. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781399502672-015. [ Links ]

Mayosi, B. M., J. E. Lawn, A. van Niekerk, D. Bradshaw, S. S. Abdool Karim, and H. M. Coovadia. 2012. "Health in South Africa: Changes and Challenges since 2009." The Lancet 380 (9858): 2029-2043. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61814-5. [ Links ]

Mbiti J. S. 1985. African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann. [ Links ]

McLeod, S. 2018. "Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs." Canada College. Simply Psychology. https://canadacollege.edu/dreamers/docs/Maslows-Hierarchy-of-Needs.pdf. [ Links ]

Michael, M. 2022. "Healing Borders and the Mapping of Referral Systems." Journal of Religion in Africa 51 (1-2): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-12340198. [ Links ]

Mpofu, E., T. M. Dune, D. D. Hallfors, J. Mapfumo, M. M. Mutepfa, and J. January. 2011. "Apostolic Faith Church Organization Contexts for Health and Wellbeing in Women and Children." Ethnicity & Health 16 (6): 551-566. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2011.583639. [ Links ]

Msomi, V.. 1967. The healing team. "In Report of the Umpumulo Consultation on the Healing Ministry of the Church. " Lutheran Theological College, Maphumulo, Natal, South Africa, 19-27 September 1967 [ Links ]

Naylor, C., M. Parsonage, D. McDaid, M. Knapp, M. Fossey, and A. Galea. 2012. "Long-Term Conditions and Mental Health: The Cost of Co-Morbidities," February. [ Links ]

Ngabo, L. 2010. Burundi 1950-1962 [Documentary film]. Burundi: Culturea ASBL, Productions Grand Lacs. [ Links ]

Ngoma, M. C., M. Prince, and A. Mann. 2003. "Common Mental Disorders among Those Attending Primary Health Clinics and Traditional Healers in Urban Tanzania." British Journal of Psychiatry 183 (4): 349-355. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.183.4.349. [ Links ]

Nhlumayo, L. N. 2021. "Review of Church Leader's Understandings of How Christian Beliefs Inform Mental Illness Identification and Remediation in Affected Members: A Scoping Review ." M.Sc Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Odejide, A. O., M. O. Olatawura, A. O. Sanda, and A. O. Oyeneye. 1978. "Traditional Healers and Mental Illness in the City of Ibadan." Journal of Black Studies 9 (2): 195-205. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2783835. [ Links ]

Olawo, J. 2021. "Review of A Lutheran Response to the Role of Healing and the Healer in African Independent Churches." M.A Thesis, Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis. [ Links ]

Orogun, D. 2020. "Review of Agencies of Capitalism: Evaluating Nigerian Pentecostalism Using African Moral Philosophies." PhD Thesis, University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Orogun, D. 2023. "Review of Improving Spiritual Care to Bridge the Gap between Demand and Supply of Healthcare Services in South Africa." In Proceedings of the 33rd International RAIS Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities, 20-28. Scientia Moralitas Research Institute. [ Links ]

Orogun, D., and J. Pillay. 2021. "African Neo-Pentecostal Capitalism through the Lens of Ujamaa." HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 77 (4). https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.6577. [ Links ]

Pardini, D. A., T. G. Plante, A. Sherman, and J. E. Stump. 2000. "Religious Faith and Spirituality in Substance Abuse Recovery." Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 19 (4): 347-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00125-2. [ Links ]

Review of Mental Healthcare. 2024. In Collins English Dictionary. California: HarperCollins Publishers. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/mental-health-care#google_vignette. [ Links ]

Review of Mental Health. 2020. In APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://dictionary.apa.org/mental-health. [ Links ]

Review of Mental Healthcare. 2020. In APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://dictionary.apa.org/mental-health-care. [ Links ]

Romero-Daza, N. 2002. "Traditional Medicine in Africa." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 583: 173-176. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271620258300111 [ Links ]

Salifu Yendork, J., L. Kpobi, and E. A. Sarfo. 2016. "'It's Only "Madness" That I Know': Analysis of How Mental Illness Is Conceptualised by Congregants of Selected Charismatic Churches in Ghana." Mental Health, Religion & Culture 19 (9): 984-999. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2017.1285877. [ Links ]

Selamu, M., L. Asher, C. Hanlon, G. Medhin, M. Hailemariam, V. Patel, G. Thornicroft, and A. Fekadu. 2015. "Beyond the Biomedical: Community Resources for Mental Health Care in Rural Ethiopia." Edited by Zi-Ke Zhang. PLOS ONE 10 (5): e0126666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0126666. [ Links ]

Schumaker, L., D. Jeater, and T. Luedke. 2007. "Introduction. Histories of Healing: Past and Present Medical Practices in Africa and the Diaspora." Journal of Southern African Studies 33 (4): 707-714. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25065246. [ Links ]

Shoshan, B. 2003. "The State and Madness in Medieval Islam." International Journal of Middle East Studies 35 (2): 329-340. https://doi.org/10.1017/s002074380300014x. [ Links ]

Solera-Deuchar, L., M. I. Mussa, S. A. Ali, H. J. Haji, and P. McGovern. 2020. "Establishing Views of Traditional Healers and Biomedical Practitioners on Collaboration in Mental Health Care in Zanzibar: A Qualitative Pilot Study." International Journal of Mental Health Systems 14 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-0336-1. [ Links ]

Sorsdahl, K., I. Petersen, B. Myers, Z. Zingela, C. Lund, and C. van der Westhuizen. 2023. "A Reflection of the Current Status of the Mental Healthcare System in South Africa." SSM - Mental Health 4 (December): 100247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmmh.2023.100247. [ Links ]

"Spiritual Care Australia." n.d. Www.spiritualcareaustralia.org.au. Accessed August 21, 2021. https://www.spiritualcareaustralia.org.au/about-us/definitions/what-is-spiritual-care/. [ Links ]

Teuton, J., C.Dowrick, and R. P. Bentall. 2007. "How Healers Manage the Pluralistic Healing Context: The Perspective of Indigenous, Religious and Allopathic Healers in Relation to Psychosis in Uganda." Social Science & Medicine 65 (6): 1260-1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.055. [ Links ]

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa. 2002. Mental Healthcare Act of 2002, Judicial Matters Amendment Act 55 of 2002. [ Links ]

Mayberry, S.. 2021. "4 Facts You Didn't Know about Mental Health in Africa." World Economic Forum. August 19, 2021. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/08/4-facts-mental-health-africa/. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. 2023. "Mental Health." World Health Organization, 2023. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_1. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. 2022. "Mental Health." World Health Organization. June 17, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response. [ Links ]

WHO. 2019. "Mortality and Global Health Estimates." Www.who.int, 2019. Accessed February 10, 2024. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. 2019. "Depression." World Health Organization, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1 [ Links ]

World Health Organization. 2007. "A Very Progressive Mental Health Law; Country Summary Series: Ghana." Www.ecoi.net. October 1, 2007. Accessed February 20, 2024 https://www.ecoi.net/en/document/1305600.html. [ Links ]

World Health Organization.1979. Schizophrenia: An International Follow-Up Study. Chichester: Wiley. [ Links ]

1 See http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/coordination/zanzibar_traditional_medicine_policy.pdf