Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Animal Science

On-line version ISSN 2221-4062Print version ISSN 0375-1589

S. Afr. j. anim. sci. vol.55 n.3 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.17159/sajas.v55i3.03

T. ChilembaI; E. van Marle-KösterI, ; A. MasengeII; M. CromhoutIII; T. NkukwanaI

IDepartment of Animal Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

IIDepartment of Statistics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

IIIRossouw Poultry, Mpumalanga, South Africa

ABSTRACT

There is considerable pressure to eliminate the use of conventional cages in commercial layer hen production systems. However, the assessment of alternative systems that can ensure the hen's ability to perform natural behaviours, while simultaneously enhancing farm productivity and economic efficiency, remains incomplete. This study assessed layer behaviour in a floor system and in enriched cages on a commercial layer farm using human and video-based observations. The study focused on dust bathing, nesting, feather pecking, and perching behaviours, and on the formation of mud balls on the feet. A large proportion (72.9%) of the hens exhibited dust-bathing behaviour, with an average duration of 22.63 minutes. Feather pecking was exhibited by 35.4% of layers in the enriched cages, compared to 58.3% of layers in the floor system. Overall, feather pecking was the least observed behaviour. Layers in enriched cages used perches more (47%) than layers in the floor system (27%), and a negative association was found between body weight and perching in layers in the floor system. At the end of the six-week trial period, 41.67% of the hens had developed mud balls on their toes that exceeded 3 cm in length. The results of this study provide evidence of the relationships between poultry behaviour, welfare, and production. Video-based observations confirmed that farm managers may not be able to identify certain welfare-related behavioural aspects unless they are closely monitored. The results of this study may be used to inform stakeholders about behaviour and welfare considerations in the management of commercial layers.

Keywords: dust bathing, feather pecking, laying hens, nesting, perching, welfare

Introduction

The poultry industry is the largest agricultural sector in South Africa, with a 20% contribution to the gross domestic product and a 41% share of the total contribution of livestock-based agriculture to the gross domestic product (AgriSETA, 2023). Commercial egg production is characterised by high-intensity housing, mostly in cage systems that are designed to maximise productivity and profitability. In general, poultry producers seek to uphold appropriate animal husbandry practices, but chicken welfare, as perceived by animal welfare organisations, is not considered a priority. Commercial poultry farmers are confronted with several issues, including disease control and biosecurity regulations, which are important for the overall sustainability of their enterprises (SAPA, 2022).

In response to growing animal welfare concerns, there has been a recent increase in interest in cage systems designed to improve the welfare of layers, while also reducing production costs. In addition, retailers have expressed their preference for cage-free and free-range eggs, rather than those produced by battery caged layers (Al-Ajeeli et al., 2018). It is hard to overlook the growing number of animal welfare organisations in South Africa, such as Compassion in World Farming (South Africa) and the Humane Society International Africa, who have requested the adjustment of present conventional cage sizes of 450 cm2 per hen to larger cages that provide additional space for movement and the expression of natural behaviour. Eliminating the use of battery cages is the extreme option, and the development of alternative systems and improved management practices, combined with the adoption of minimum standards for enriched cage systems, is thus of paramount importance.

Conventional cages have the advantages of reducing disease risk, producing cleaner eggs, and being easier to manage, but they also result in space restrictions, which lead to poor bone strength due to the lack of movement (Dikmen et al., 2016; Hartcher & Jones, 2017). Higher incidences of metabolic disorders are also associated with conventional cages. The scientific investigation of the physiological and behavioural characteristics of proactive and reactive choices and decision-making in avian species, including laying hens, has received little attention (Nicol et al., 2003). Nonetheless, guidelines from the World Organisation for Animal Health indicate that birds should be able to express their natural behaviours, such as nesting, scratching, pecking, and dust bathing, without fear (Bhanja & Bhadauria, 2018).

Current commercial laying cage densities restrict the expression of acceptable natural behaviours and movement. However, floor systems have their own challenges for bird welfare, especially at higher stocking densities, where social behaviour becomes more stressful, leading to higher incidences of cannibalism (Dikmen et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2021). Aggression in domestic fowl species has been shown to be a dynamic process determined by the relative costs and benefits of different behavioural strategies at a given time and place, rather than being a fixed continual obligation (Campbell et al., 2017). Birds in floor systems are therefore also vulnerable to poor welfare, if the stocking density is too high and/or insufficient food and perch space is provided (Erensoy et al., 2021).

Literature studies have reported pros and cons of conventional cages, enriched cages, and floor systems related to egg production, mortality, and bone strength. While floor systems hold clear advantages for bone strength (Hartcher & Jones, 2017), keel bone fractures tend to be more common in these systems, and increased feather pecking has been reported (Engel et al., 2019). There thus seems to be limited consensus on which production system provides the best overall layer welfare. In South Africa, most layer birds are housed in cage systems, with approximately 7.28% of eggs produced on floors in deep litter; in some cases, pullets are raised on floors for later use in free-range systems (SAPA, 2022). In this study, layer behaviour in a floor system and in an enriched cage scenario on a commercial layer farm in South Africa was evaluated using human and video-based observations of dust bathing, nesting, feather pecking, and perching behaviours. Body weight, as well as feather and plumage condition, were also assessed.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted on a commercial farm in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where both floor and cage systems are used for the production of fresh eggs. The producer provided consent for the study and the Animal Ethics Committee of the University of Pretoria granted approval to conduct the study (NAS269/2020). The South African Poultry Association's Code of Practice Guide (SAPA, 2018) was used to allocate stocking densities and space per bird.

Layers in the floor system

The study was conducted over a six-week period with a two-week adaptation period prior to data collection, and used Lohmann Brown laying hens housed in an open-sided, naturally-ventilated house with the following dimensions: 57 × 2.5 × 14 m (length × height × width). A 12.5 × 2.5 × 4 m section was partitioned off using wire mesh, to house 500 birds at a stocking density of 10 birds/m2 and a space allowance of 1000 cm2/bird. Seventy-five nesting boxes were allocated to allow access to eight hens at a time. A total of 48 beak-trimmed laying hens aged 47 weeks were randomly selected from the 500 birds and tagged on both legs using adjustable numbered white straps that could be easily identified on video recordings and by human observers.

The house was equipped with 50 nipple drinkers, allowing 12 birds per nipple, and 12 cm of feeding space was available per bird. Ten perches were provided, each with five metal bars (150 cm long, 3.1 cm in diameter), giving each hen a space allowance of 15 cm. An elevated scaffold was placed against the back wall to enable visual observations without interfering with the layers' behaviour. The house had doors that were opened during the day to allow access to the fenced outdoor space, which was planted with kikuyu grass.

Layers in the enriched cage system

For the purposes of the study, eight wire cages in one of the environmentally controlled houses were modified to a size of 120 χ 50 χ 64.3 cm (length × height × width) to mimic the requirements for an enriched cage. Each cage included a nesting area and a perch that was 120 cm long and 3.1 cm in diameter, with a perching space allowance of 15 cm per hen. Each cage housed six 27-week-old hens, resulting in a stocking density of 750 cm2/bird, excluding the nesting boxes. Twenty-seven-week-old hens were used because, at the time of the study, there were no 47-week-old Lohmann Brown hens in any of the farm's cage housing systems. Each cage system was equipped with a waterline containing two nipples, and an automatic gantry feeding system was used.

Human and video-based observation of laying hens

The study used human and video-based observations to examine the behaviour of the hens in both the floor and enriched cage systems. Hens were given a two-week adaptation period prior to data collection to allow them to get familiar with humans observing them. During this period, the in-farm veterinarian and the researcher on the project trained ten selected staff members on how to monitor and document different hens' behaviours. In each of the two housing systems, a trained observer collected data within the specified period without interfering with the hens' behaviour.

Video cameras were used to record the different behaviours at two-minute intervals. Data from the video cameras were used to validate the data collected by the trained human observers, and inter-and intra-observer reliability tests were performed on both data sets. This was achieved by comparing the data derived from human observations with the data captured from video recordings to determine the level of agreement between the sources.

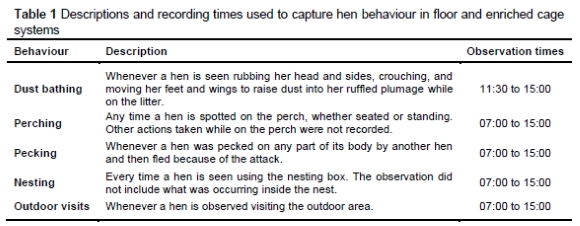

In the floor system, behavioural observations were made of the 48 tagged hens. In the enriched cage system, feather pecking, nesting, and perching behaviours were observed for all 48 hens. The major behavioural components of dust-bathing events recorded in the floor system were bill raking, head rubbing, scratching with either one or two legs, side-lying, ventral lying, and vertical wing shaking (Kruijt, 1964). A dust-bathing event was recorded from when the hen's body touched the litter until the hen got up and failed to perform any of the dust-bathing behaviours for a 10-second period. Since chickens have a daily circadian cycle, dust bathing most often occurs in the afternoon, so data was collected between 11:30 and 15:00 (Mishra et al., 2005). Human observations and video data collection on feather pecking, outdoor area visitation, perching, and nesting activities were recorded between 07:00 and 15:00, as described in Table 1.

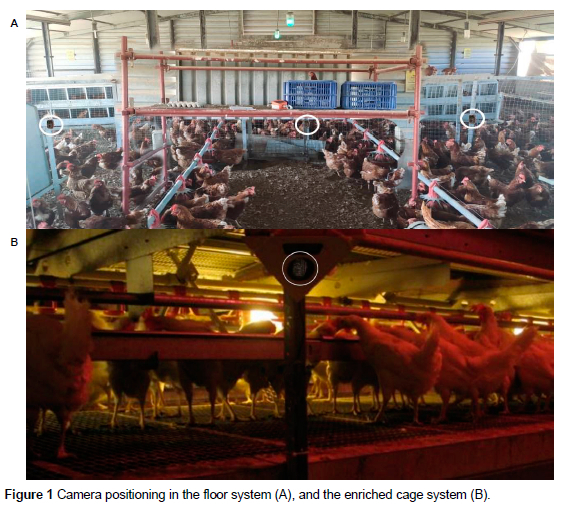

Description of camera installations

High-definition digital surveillance cameras (Bushnell Trophy Cam HD, model number: 119774) were installed in the enriched cages and floor housing systems to capture footage of various hen behaviours. Ten cameras were used in the floor system, with one in each corner of the house (four in total) and the other six positioned one metre apart in the middle of the area, directly opposite one another (Figure 1A). All the cameras were set 0.5 m above the ground for maximum visibility. Four cameras were used in the enriched cage system, and these were set up in one row, as shown in Figure 1B. All video recordings were saved daily on an external hard drive.

Feather, plumage, and mud balls

Feathers on the neck, breast, vent, back, wings, and tail, as well as the condition of wounds on the back and comb, were scored on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1 representing the worst possible score and 4 representing the best possible score (Tauson et al., 2005). Inter- and intra-repeatability tests were done on the subjective scores collected by the researcher and two staff members.

The sizes of the mud balls on the hens' feet in the floor system were measured using a ruler, and scores were assigned as 0: no mud ball, 1: mud ball of 1-2 cm, 2: mud ball of 2-3 cm, and 3: mud balls >3 cm in length. Hens were weighed at the start and end of the six-week observation period.

Data collection and analyses

An electronic data collection tool was developed to record various behaviours, as well as feather and plumage scores, through coding and programming using CSPro v7.5. Logic, skip patterns, and consistency checks were used during data collection to prevent entry problems, and data were collected using Android operating system smartphones. Changes made on the applications were uploaded to the file transfer protocol server such that data could be downloaded, or changes made on the form. Once data had been uploaded to the file transfer protocol server, they were checked and exported to Microsoft Excel for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics 27 was used to analyse the data for descriptive statistical means and standard deviations, and frequency and percentage counts. Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) was used to estimate correlations between behavioural events and body weight (McHugh, 2012). The Shapiro-Wilk test (McHugh, 2012) was performed to test for normal distribution, and Fleiss' multi-rater kappa was used to determine the level of agreement between the raters on feather and plumage scores and the data collected using human and video-based observations (Fleiss, 1971).

Results

Behavioural parameters

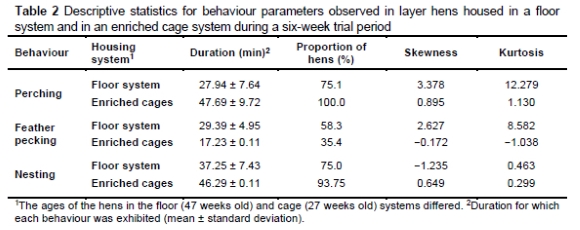

Of the 48 tagged hens in the floor system, 79.2% engaged in dust bathing for an average duration of 22.63 ± 2.13 minutes. The shortest time observed for dust bathing was one minute, while the longest was 32 minutes. Additionally, 91.7% of the 48 tagged hens in the floor system utilised the outdoor area. The behaviours observed in both systems over the six-week study period are summarised in Table 2. The least prevalent behaviour observed was feather pecking in the enriched cage system, with an average of 35.4% of hens being pecked.

All the observed behaviours exhibited asymmetric distribution, as indicated by their non-zero skewness values. Nevertheless, the activity of dust bathing appeared to be nearly symmetrical, as indicated by a skewness value of 0.367. An extremely uneven distribution was found for perching, with a skewness value of 3.378.

At the end of the six-week trial period, only 27.08% of the 48 tagged birds in the floor system did not have any mudballs, while 12.50% had mudballs with a score of 1, 18.75% had mudballs with a score of 2, and 41.67% had mudballs with a score of 3.

At the start of the trial, the average body weights of the 48 tagged hens in the floor system and the 48 hens in the enriched cages were 2.10 ± 0.27 kg and 1.83 ± 0.17 kg, respectively. By the end of the trial, the average weight in the floor system had decreased to 1.90 ± 0.31 kg, while in the enriched cages it had increased to 2.14 ± 0.13 kg.

Associations between behavioural parameters and body weight

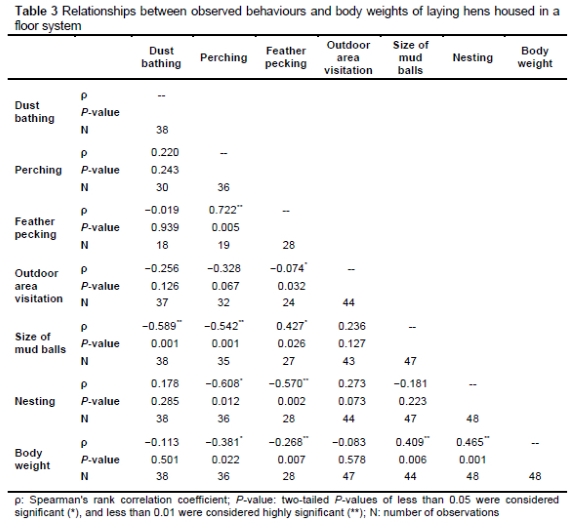

Spearman's rank correlation coefficient was employed to determine the association between the different behaviours and body weight. Table 3 shows the Spearman's rank correlation coefficient pairs for the floor system, with positive correlations being found between body weight and the size of mud balls, body weight and nesting behaviour, size of mud balls and feather pecking, and feather pecking and perching behaviour (P <0.05). The negatively correlated behavioural and production parameter pairs with P <0.05 were body weight and perching, body weight and feather pecking, nesting and perching, nesting and feather pecking, size of mud balls and dust bathing, feather pecking and perching, and feather pecking and outdoor area visitation.

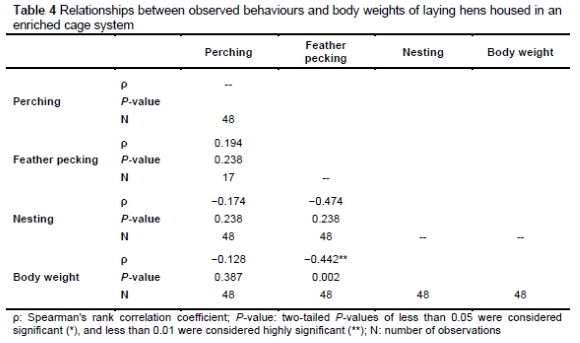

The correlations observed between the different measured behaviours and body weight for the 48 hens in the enriched cage system can be seen in Table 4, with their corresponding significance levels. Feather pecking behaviour and body weight were the only pair with a statistically significant correlation coefficient (ρ = 0.442).

Intra- and inter-repeatability of feather condition and behavioural parameter scoring

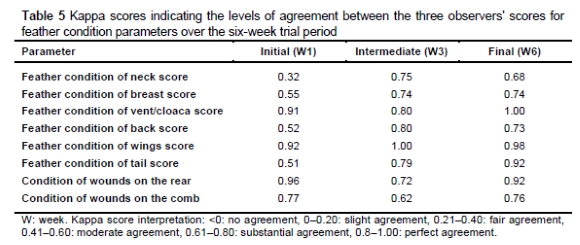

Kappa scores were used to indicate the levels of agreement between the three observers in the hens' body condition scores (feather and plumage), where 0.61-0.80 is the range indicating an acceptable level of agreement. The three observers had initial levels of agreement ranging from 0.3 to 0.77, indicating a fair degree of agreement, with higher levels of agreement (>0.6) being recorded from week 3 to week 6, especially for neck feather condition scores (Table 5).

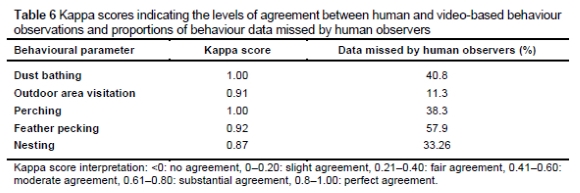

In Table 6, the kappa scores for the levels of agreement between the behavioural parameter data collected using human observation and collected using video cameras are shown.

Perfect agreement was observed for all parameters; however, some behavioural data were missed during human observation and were recovered from the video recorded data. The highest percentage of data missed by human observers was for feather pecking (57.9%), with 40.8% of dust-bathing events also missed by the human observers.

Discussion

Worldwide, consumer awareness of free-range layer production has increased, coupled with considerable pressure by animal welfare organisations to eliminate the use of conventional cages in commercial layer production systems (Glatz & Underwood, 2020). This highlights the need for housing systems that simultaneously meet the welfare needs of chickens, while also keeping production costs low. To date, this is the first field study in South Africa to describe behavioural parameters under commercial farm conditions using human and camera-based observations.

Behavioural parameters

In this study, hens in the floor system spent 22.63 minutes dust bathing, on average. Several previous studies have observed similar dust-bathing events, which varied in duration between 20 and 27 minutes (Van Liere et al., 1990; Sewerin, 2002), and in some instances lasted up to 45 minutes (Moesta et al., 2008). Previous research has reported that an average of 66.6% of hens exhibit dust-bathing behaviour (Vestergaard, 1982), which is slightly lower than the average of 79.2% of hens observed dust bathing in this study. The practical purposes of dust bathing are preening, the elimination of skin parasites, and the preservation of plumage quality and lipid content (Olsson & Keeling, 2005; Lay Jr et al., 2011). The incentive to dust bath is inconclusive, with research failing to find evidence of the hens' desire to do so (Lay Jr et al., 2011). The duration and frequency of dust-bathing behaviours depends on housing condition and breed type (Van Rooijen, 2005).

Most free-range hens are reported to prefer to remain near the hen house, rather than visiting designated outdoor spaces (Keeling, 1988; Hegelund et al., 2005). In contrast to decreasing the indoor stocking density, providing access to outdoor areas has a space advantage, which stimulates greater mobility and the expression of innate behaviours, such as foraging and exploring (Knierim, 2006). In this study, 91.7% of the tagged hens used the outdoor area, which is a much higher proportion than the 15% in large flocks (>30000 birds) and the 40% in small flocks (1-1000 birds) reported by Hegelund et al. (2005). Shimmura et al. (2008) reported that 61.5% of hens reared in a small flock used the outdoor area.

In this study, perching behaviour was exhibited by 75% and 100% of hens in the floor and enriched cage systems, respectively. This was likely because perches were the only available option for the expression of natural behaviour in the cage system, other than the nest boxes. The percentage of hens using perches was higher than the 55% reported by the Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC, 2010). Although cage or perch height was not measured in the current study, these factors do also influence perching behaviour. Perching structures are critical for maximising the use of available space in floor systems (Cordiner & Savoury, 2001). The enriched cage results agree with those of Hester et al. (2014), who reported that, irrespective of the cage system used, 85% to 100% of hens in the flock used perching structures during the day.

Feather pecking is a major economic and welfare concern across all housing systems (Bestman et al., 2009). This behaviour is often initiated by a few birds and will then spread, if not curbed early (Bessei & Kjaer, 2015), and may be worse in larger groups with higher stocking densities (Pötzsch et al., 2001). Feather pecking was the least frequently observed behaviour in this study, but was more prevalent among the hens in the floor system than among those in the enriched cages. Coton et al. (2019) reported that 32.9% of hens exhibited feather-pecking behaviour in enriched cages, and 23.8% of hens exhibited this behaviour in a floor system. This is in contrast with the results of the current study, in which higher frequencies of feather pecking were observed in the floor system (58.3%) than in the enriched cages (35.4%).

Kappa scores for both systems showed substantial or higher levels of agreement for feather-pecking wounds on the cloaca and wings from the initial to the final week of observation. Literature suggests that flock size, rather than stocking density per se, has a significant effect on plumage condition, and that this is potentially an important mediating factor for feather pecking (McKeegan & Savory, 1999; Struelens & Tuyttens, 2009). In layer flocks, aggression may be an indication that the housing system does not satisfy the hens' behavioural and welfare needs at a given time and place (Weeks & Nicol, 2006), rather than being a fixed and continual obligation (Bilcik & Keeling, 2000).

No significant effects were observed on nesting behaviour, which was less prevalent in the floor system (75%) than in the enriched cages (93.75%). Zimmerman et al. (2000) reported that hens were more frustrated by nest box removal than by feed and water deprivation. The prioritising of nesting behaviour therefore improves hen health and well-being (Weeks & Nicol, 2006; Widowski et al. 2013). The utilisation of nests for egg-laying purposes is also beneficial to farmers, as nest-laid eggs are cleaner than those laid on the floor or litter (Dikmen et al. 2016).

Another welfare concern is the presence of moisture in wet litter or in wet soil in free-range systems, which causes muddy surfaces and, consequently, dry clumps of mud on hens' feet. Despite the lack of research on the occurrence of dry mud balls on toes, the removal of dirt should be considered a management practice for enhancing bird welfare. Dry mud balls measuring more than 3 cm in length were observed on the toes of 41.67% of the hens at the end of the six-week study period. Widowski et al. (2016) emphasised the importance of feet for the performance of activities such as locomotion, perching, and self-grooming. Physical impediments may thus restrict movement and limit certain behavioural activities (Hartcher & Jones, 2017).

Associations between behavioural parameters and body weight

A negative correlation between feather pecking and body weight was seen in the enriched cages (P = 0.002). The continuous pecking of feathers by fellow layers resulted in the deterioration of the victims' plumage and prompted the affected birds to seek refuge and protection (Cronin & Glatz 2020). The reduced mobility and increased stress levels of layers attempting to avoid being pecked may lead to a decrease in their daily intake of feed and water. This may result in a decline in their overall weight, which could explain the observed negative correlation.

Nesting behaviour was positively correlated (ρ = 0.465) with body weight. As hens instinctively engage in nesting behaviour (Weeks & Nicol, 2006), it can be deduced that an increase in hen weight will result from improved welfare conditions, such as better accessibility of food and water and fewer instances of feather pecking, and that this is also linked to a corresponding increase in nesting behaviour. Previous studies have reported positive correlations between body weight and egg production (Hester et al., 2013; Luchkin et al. 2021), although reports on the association between nesting behaviour and body weight are limited.

The present study found a negative correlation between feather pecking and nesting behaviour, with pecked hens avoiding the nest boxes and preferring the protection of perching structures. This change in behaviour leads to a decrease in the amount of time that the hens spend in the nesting boxes, which subsequently impacts their egg-laying habits (Cronin et al., 2008). The observed inverse relationship between nesting and perching behaviours can be attributed to feather pecking, with layers that are being pecked spending longer perching and less time in the nest boxes (Cronin & Glatz 2020).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the association between the size of dry mud balls and hen behaviour. Over the study period, hens accumulated mud balls due to water spillages while drinking and/or occasional leakages. Birds with lower weights tended to have fewer mud balls and were subjected to more pecking, and thus spent more time on the perches. The observed significant positive correlation between body weight and the size of the mud balls formed suggests that birds with higher body weights had sufficient opportunity to drink water, and thus potentially spent more time standing on muddy surfaces. Fanatico et al. (2009) found that chickens provided with enough feed and water did not engage in frequent running, and were thus more likely to gain weight.

Mud balls on the hens' toes inhibited hens from dust bathing and perching, because of their inability to maintain balance. Hens may experience frustration and distress if they are unable to engage in natural behaviours, and may then resort to feather pecking as a form of aggression (Lay Jr et al., 2011). The significant positive correlation found between mud ball size and feather pecking could be explained by the fact that when their mud balls became larger, these hens (N = 27) were unable to perform their preferred behaviours, such as nesting and dust bathing, leading to frustration and subsequently feather pecking. Studies have found decreased levels of frustration and feather-pecking incidences in housing systems where the hens could express behaviours like nesting, perching, and dust bathing (Widowski et al., 2013).

Inter- and intra-observer repeatability for body condition scoring

A high level of agreement (ρ >0.8) was found between the data collected through video recordings and the data collected through human observation by three observers for feather scores, which agrees with the findings of Milisits et al. (2021). It may be less challenging to observe a specific activity or condition using video recordings than it is to conduct a physical assessment of the condition. According to Bateson & Martin (2021), correlations should have ρ values near or below 0.7, unless the measured parameters are significant and pose challenges for measurement. Multiple scorers monitoring identical parameters is necessary to avoid bias. In the first week, one examiner gave higher scores for the tail and wing feathers, but this was corrected by the third week, after feedback and as the observer's skills improved over time. Video recordings proved reliable for the precise capturing of behavioural events for welfare monitoring.

Conclusions

The results of this study confirmed the need for layer hens to exhibit natural behaviours in both a floor system and in enriched cages. Certain negative behaviours and outcomes may not be obvious to farm managers unless they are closely and regularly observed, and video-based observations can thus be beneficial for monitoring. When hens encounter minimal hindrances impeding their natural movements, such as when there are few to no mud balls present, they are more likely to engage in dust bathing and perching activities. Paying attention to the behaviours observed and monitored in this study should promote sound bird welfare and, when combined with appropriate management, should also optimise hen productivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Rossouw Poultry, Mpumalanga, South Africa, for the resources used in this study and for their support of the post graduate student. The University of Pretoria is also thanked for their provision of a postgraduate bursary.

Authors' contributions

The manuscript was conceptualised by T.Chilemba, E. van Marle-Köster, T. Nkukwana, and M. Cromhout. A. Masenge performed the statistical analyses and T. Chilemba prepared the draft. All authors contributed to the discussion and final editing of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

AgriSETA, 2023. Agriculture sector skills plan. Agriculture Sector Education Training Authority, Pretoria, South Africa. Available at https://www.agriseta.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Agriseta_Sector-Skills-Plan-2023-24.pdf [ Links ]

Al-Ajeeli, M., Miller, R., Leyva, H., Hashim, M., Abdaljaleel, R., Jameel, Y., & Bailey, C., 2018. Consumer acceptance of eggs from Hy-Line Brown layers fed soybean or soybean-free diets using cage or free-range rearing systems. Poultry Science, 97(5):1848-1851. DOI: 10.3382/ps/pex450 [ Links ]

Bessei, A. & Kjaer, J., 2015. Feather pecking in layers-state of research and implications. In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium. Sydney, Australia. [ Links ]

Bateson, M. & Martin, P., 2021. Measuring behaviour: an introductory guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England. [ Links ]

Bilčik, B. & Keeling, L.J., 2000. Relationship between feather pecking and ground pecking in laying hens and the effect of group size. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 68(1):55-66. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00089-7 [ Links ]

Bestman, M., Koene, P., & Wagenaar, J.P., 2009. Influence of farm factors on the occurrence of feather pecking in organic reared hens and their predictability for feather pecking in the laying period. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 121(2):120-125. DOI: 10.1016/j.applanim.2009.09.007 [ Links ]

Bhanja, S. & Bhadauria, P., 2018. Behaviour and welfare concepts in laying hens and their association with housing systems. Indian Journal of Poultry Science, 53:1-10. [ Links ]

Campbell, D., Hinch, G., Dyall, T., Warin, L., Little, B., & Lee, C., 2017. Outdoor stocking density in free-range laying hens: radio-frequency identification of impacts on range use. Animal, 11(1):121-130. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00186-6 [ Links ]

Cordiner, L. & Savoury, C., 2001. Use of perches and nestboxes by laying hens in relation to social status, based on examination of consistency of ranking orders and frequency of interaction. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 71(4):305-317. [ Links ]

Coton, J., Guinebretière, M., Guesdon, V., Chiron, G., Mindus, C., Laravoire, A., Pauthier, G., Balaine, L., Descamps, M., & Bignon, L., 2019. Feather pecking in laying hens housed in free-range or furnished-cage systems on French farms. British Poultry Science, 60(6):617-627. DOI: 10.1080/00071668.2019.1639137 [ Links ]

Cronin, G., Downing, J., Borg, S., Storey, T., Schirmer, B., Butler, K., & Barnett, J., 2008. The importance of nest-boxes to young adult laying hens: effects on stress physiology. World's Poultry Science Journal, 64(Suppl. 2):243. [ Links ]

Cronin, G.M. & Glatz, P.C., 2020. Causes of feather pecking and subsequent welfare issues for the laying hen: a review. Animal Production Science, 61(10):990-1005. DOI: 10.1071/AN19628 [ Links ]

Dikmen, B.Y., Ipek, A., Şahan, Ü., Petek, M., & Sözcü, A., 2016. Egg production and welfare of laying hens kept in different housing systems (conventional, enriched cage, and free range). Poultry Science, 95(7):1564-1572. DOI: 10.3382/ps/pew082 [ Links ]

Engel, J., Widowski, T., Tilbrook, A., Butler, K., & Hemsworth, P., 2019. The effects of floor space and nest box access on the physiology and behavior of caged laying hens. Poultry Science, 98(2):533-547. DOI: 10.3382/ps/pey378 [ Links ]

Erensoy, K., Sarıca, M., Noubandiguim, M., Dur, M., & Aslan, R., 2021. Effect of light intensity and stocking density on the performance, egg quality, and feather condition of laying hens reared in a battery cage system over the first laying period. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 53(2):320. DOI: 10.1007/s11250-021-02765-5 [ Links ]

Fanatico, A., Owens, C., & Emmert, J.L., 2009. Organic poultry production in the United States: Broilers. Journal of Applied Poultry Research, 18(2):355-366. DOI: 10.3382/japr.2008-00123 [ Links ]

FAWC, 2010. Opinion on osteoporosis and bone fractures in laying hens. Farm Animal Welfare Council, London, England. [ Links ]

Fleiss, J.L., 1971. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin, 76(5):378. [ Links ]

Glatz, P.C. & Underwood, G., 2020. Current methods and techniques of beak trimming laying hens, welfare issues and alternative approaches. Animal Production Science, 61(10):968-989. DOI: 10.1071/AN19673 [ Links ]

Hegelund, L., Sørensen, J., Kjaer, J., & Kristensen, I., 2005. Use of the range area in organic egg production systems: effect of climatic factors, flock size, age and artificial cover. British Poultry Science, 46(1 ):1-8. DOI: 10.1080/00071660400023813 [ Links ]

Hester, P., Garner, J., Enneking, S., Cheng, H.W., & Einstein, M., 2014. The effect of perch availability during pullet rearing and egg laying on the behavior of caged White Leghorn hens. Poultry Science, 93(10):2423-2431. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2014-04038 [ Links ]

Hartcher, K.M. & Jones, B., 2017. The welfare of layer hens in cage and cage-free housing systems. World's Poultry Science Journal, 73(4):767-782. DOI: 10.1017/S0043933917000812 [ Links ]

Hester, P., Enneking, S., Jefferson-Moore, K., Einstein, M., Cheng, H.W., & Rubin, D., 2013. The effect of perches in cages during pullet rearing and egg laying on hen performance, foot health, and plumage. Poultry Science, 92(2):310-320. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2012-02744 [ Links ]

Keeling, L., 1988. Performance of free-range laying hens in a polythene house and their behaviour on range. Farm Building Progress, 94, 21-28. [ Links ]

Knierim, U., 2006. Animal welfare aspects of outdoor runs for laying hens: a review. NJAS: Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 54(2):133-145. DOI: 10.1016/S1573-5214(06)80017-5 [ Links ]

Kruijt, J.P., 1964. Ontogeny of social behaviour in Burmese red junglefowl (Gallus gallus spadiceus) Bonnaterre. Behaviour Supplement, I-201. [ Links ]

Kumar, M., Ratwan, P., Dahiya, S., & Nehra, A.K., 2021. Climate change and heat stress: Impact on production, reproduction and growth performance of poultry and its mitigation using genetic strategies. Journal of Thermal Biology, 97:102867. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.102867 [ Links ]

Lay Jr, D., Fulton, R., Hester, P., Karcher, D., Kjaer, J., Mench, J.A., Mullens, B., Newberry, R.C., Nicol, C.J., & O'Sullivan, N.P., 2011. Hen welfare in different housing systems. Poultry Science, 90(1):278-294. DOI: 10.3382/ps.2010-00962 [ Links ]

Luchkin, A., Lukasheva, O., Novikova, N., Zyatkova, A., & Yarotskaya, E., 2021. Feasibility study of the influence of the diet on the quality characteristics of poultry production. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 640:032041. DOI: 10.1088/1755-1315/640/3/032041 [ Links ]

McKeegan, D.E.F. & Savory, C.J., 1999. Feather eating in layer pullets and its possible role in the aetiology of feather pecking damage. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 65:73-85. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00051-9 [ Links ]

Milisits, G., Szász, S., Donkó, T., Budai, Z., Almási, A., Pöcze, O., Ujvári, J., Farkas, T.P., Garamvölgyi, E., & Horn, P., 2021. Comparison of changes in the plumage and body condition, egg production, and mortality of different non-beak-trimmed pure line laying hens during the egg-laying period. Animals, 11(2):500. DOI: 10.3390/ani11020500 [ Links ]

Mishra, A., Koene, P., Schouten, W., Spruijt, B., Van Beek, P., & Metz, J., 2005. Temporal and sequential structure of behavior and facility usage of laying hens in an enriched environment. Poultry Science, 84(7):979-991. DOI: 10.1093/ps/84.7.979 [ Links ]

Moesta, A., Knierim, U., Briese, A., & Hartung, J., 2008. The effect of litter condition and depth on the suitability of wood shavings for dustbathing behaviour. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 115(3-4):160-170. DOI: 10.1016/j.applanim.2008.06.005 [ Links ]

Nicol, C., Pötzsch, C., Lewis, K., & Green, L., 2003. Matched concurrent case-control study of risk factors for feather pecking in hens on free-range commercial farms in the UK. British Poultry Science, 44(4):515-523. DOI: 10.1080/00071660310001616255 [ Links ]

Olsson, I.A.S. & Keeling, L.J., 2005. Why in earth? Dustbathing behaviour in jungle and domestic fowl reviewed from a Tinbergian and animal welfare perspective. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 93(3-4):259-282. DOI: 10.1016/j.applanim.2004.11.018 [ Links ]

Pötzsch, C., Lewis, K., Nicol, C., & Green, L., 2001. A cross-sectional study of the prevalence of vent pecking in laying hens in alternative systems and its associations with feather pecking, management and disease. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 74(4):259-272. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-1591(01)00167-8 [ Links ]

SAPA, 2018. Code of practice guide 2018. South Africa Poultry Association, Randburg, South Africa. Available at: http://www.sapoultry.co.za/pdf-docs/code-of-practice-sapa.pdf. [ Links ]

SAPA, 2022. Code of practice guide 2022. South Africa Poultry Association, Randburg, South Africa. Available at: https://www.sapoultry.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022-SAPA-COP.pdf. [ Links ]

Shimmura, T., Suzuki, T., Hirahara, S., Eguchi, Y., Uetake, K., & Tanaka, T., 2008. Pecking behaviour of laying hens in single-tiered aviaries with and without outdoor area. British Poultry Science, 49(4):396-401. DOI: 10.1080/00071660802262043 [ Links ]

Struelens, E. & Tuyttens, F.A.M., 2009. Effects of perch design on behaviour and health of laying hens. Animal Welfare, 18:533-538. DOI: 10.1017/S0962728600000956 [ Links ]

Tauson, R., Kjaer, J., Maria, G., Cepero, R., & Holm, K., 2005. Applied scoring of integument and health in laying hens. Animal Science Papers and Reports, 23(Suppl 1):153-159. [ Links ]

Van Liere, D., Kooijman, J., & Wiepkema, P., 1990. Dustbathing behaviour of laying hens as related to quality of dustbathing material. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 26(1-2):127-141. DOI: 10.1016/0168-1591(90)90093-S [ Links ]

Van Rooijen, J., 2005. Dust bathing and other comfort behaviours of domestic hens. Das Wohlergehen von Legehennen in Europa-Berichte, Analysen und Schlussfolgerungen. Wageningen: Internationale Gesellschaft für Nutztierhaltung IGN, 110-123. [ Links ]

Vestergaard, K., 1982. Dust-bathing in the domestic fowl-diurnal rhythm and dust deprivation. Applied Animal Ethology, 8(5):487-495. DOI: 10.1016/0304-3762(82)90061-X [ Links ]

Weeks, C. & Nicol, C., 2006. Behavioural needs, priorities and preferences of laying hens. World's Poultry Science Journal, 62(2):296-307. DOI: 10.1079/WPS200598 [ Links ]

Widowski, T.M., Classen, H., Newberry, R., Petrik, M., Schwean-Lardner, K., Cottee, S., & Cox, B., 2013. Code of practice for the care and handling of pullets, layers, and spent fowl: poultry (layers): review of scientific research on priority issues. National Farm Animal Care Council, Lacombe, Canada. [ Links ]

Widowski, T., Hemsworth, P., Barnett, J., & Rault, J.L., 2016. Laying hen welfare I. Social environment and space. World's Poultry Science Journal, 72(2):333-342. DOI: 10.1017/S0043933916000027 [ Links ]

Zimmerman, P.H., Koene, P., & van Hooff, J.A., 2000. Thwarting of behaviour in different contexts and the gakel-call in the laying hen. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 69(4):255-264. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-1591(00)00137-4 [ Links ]

Submitted 28 August 2024

Accepted 27 January 2025

Published March 2025

# Corresponding author: evm.koster@up.ac.za