Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.81 n.1 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v81i1.10518

REVIEW ARTICLE

Christian communities and intimate partner violence in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review

Elorm A. Stiles-Ocran; Annette R. Leis-Peters

Centre for Diakonia and Professional Practice, Faculty of Social Science, VID Specialized University, Oslo, Norway

ABSTRACT

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a growing development concern affecting women globally including sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). However, knowledge of the involvement of Christian faith communities with IPV and their work on the empowerment of survivors of IPV in SSA is currently vague. The aim of this scoping study was to provide an overview of documented studies conducted in this area as well as identify possible gaps for empirical research. The authors employed a six-step strategy for scoping studies. The search strategies involved electronic searches in nine databases and academic search engines between 11 September 2021 to 23 January 2024. Manual searches in bibliographies were also carried out for grey literature, and one additional study was recommended by stakeholders in consultation with them. The selected studies were analysed for themes and patterns in relation to the research questions and aims. Findings indicate a growing interest in this field of research over the past few years. However, there is inadequate representative knowledge of IPV in SSA and how Christian faith communities deal with it. It is also striking that colonialism and post-colonialism are hardly mentioned in the reviewed research work. From the analysis, it is obvious that faith communities and faith leaders have the potential to fight IPV.

CONTRIBUTION: The article highlights the areas within the important research field of religion and IPV that have been explored in SSA, as well as the significant gaps that remain. It emphasises the need for multidisciplinary and interconnected approaches to address these gaps

Keywords: gender-based violence; intimate partner violence; sub-Saharan Africa; faith communities; churches; faith-based organisations; scoping review.

Introduction

Violence against women (VAW) is a critical concern from human rights, health and development perspectives both nationally and globally. According to the United Nations (UN), about one in three women worldwide have experienced one form of violence in their lifetime (World Health Organization [WHO] 2021:XII). Of the various forms of VAW, intimate partner violence (IPV), predominantly defined as any act of controlling behaviour and physical, sexual and psychological aggression or abuse in an intimate relationship, contributes to a high incidence of this scourge (WHO 2013:6, 2017:vii). It is important to note that men also experience IPV (Gathogo 2015; Taliep et al. 2023:2). However, women by far experience IPV with health effects such as depression (UN Women 2013:9-10) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS [UNAIDS] 2014:136). The interconnectedness of IPV, health and overall well-being of women highlights the urgency and significance of addressing this pervasive menace to promote gender equality, safety and empowered lives for women.

World Health Organization reports that 33% of ever married or partnered women aged 15 years-49 years in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) experience lifetime IPV (WHO 2021:23). This high incidence is characterised by men's justification of physical IPV (Darteh et al. 2021:1435) with significant economic effects both for women's development and for society (International Rescue Committee [IRC] 2012:10).

To combat VAW, there is evidently a confluence of national and international policy agendas (CEDAW 1979, Murray 1989)1. Religion plays a crucial role in these efforts. Recently, there has been a burgeoning body of literature and evidence on the involvement of religion, spirituality and faith in development (e.g. Kalkum & Istratii 2023; Marshall et al. 2021; McPhillips & Page 2021). This includes the role of religion in religious change (Freston 2015); in health (Muke 2021; Santhosh 2015); in fostering a sense of purpose (Tirri & Quinn 2010); in influencing politics (Asamoah 2017); in addressing unemployment, poverty and social injustice (Swart 2012) and in women empowerment in Africa (Njoh & Akiwumi 2012). Faith communities have been recognised to speak to issues of oppression and seek liberation and justice (Watlington & Murphy 2006) and in the provision of educational and health institutions and services (Omenyo 2006). Nadine Bowers-Du Toit (2021) maintains that local churches and faith-based organisations (FBOs) in South Africa have been instrumental in raising their voices against structures of poverty and racial discrimination.

However, it is not clear how much is known about the role of Christian faith communities in addressing IPV and supporting female survivors in SSA. This scoping review aims to determine the scope or extent of existing scientific studies in this field by examining academic literature. The research question driving this study is: What is the existing scientific knowledge on the role of Christian faith communities in addressing IPV in SSA?

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. We will begin by defining the concepts as operationalised in this study, followed by a description of the research methodology and limitations. Next, we will provide an overview of existing studies and key themes. Finally, we will discuss our findings with stakeholders before concluding briefly.

Defining terminologies

Faith communities

This article focusses specifically on Christian faith communities. Faith communities are non-profit formally registered entities that include churches and faith-based non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Other authors use FBOs as an overarching term for these kinds of organisations. Each of these terms is controversial with regard to how inclusive or exclusive they are for the huge variety of organisational forms in the field of faith-based collective activities (e.g. Vähäkangas et al. 2022). While we acknowledge that the term, faith communities, includes a plurality of faiths like African Traditional Religion (ATR), Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam, etc., it is, in this study, limited to Christian faith communities or interfaith work in which Christian faith communities participate. That includes local Christian churches and Christian non-governmental organisations (CFBOs).

Intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence is a form of VAW. It is essentially defined by the WHO as an act of gender-based violence (GBV), which constitutes sexual, physical, psychological and aggressive and controlling behaviour by an intimate partner or ex-partner (WHO 2017:vii). However, it may also include death and dehumanising cultural practices. While some studies distinguish IPV from other forms of violence (Bazargan-Hejazi et al. 2013:39), other studies alternate IPV with domestic violence (DV) (Sardenberg 2011:4) or family violence (FV) (Bernardi & Steyn 2021:39). Although IPV occurs within the context of intimate relationships in the home, DV can encompass violence within household relationships, which may not necessarily involve intimate partners. Therefore, differentiations are needed for clarity and accurate representations of the forms of violence being addressed. In this article, the terms IPV, VAW and GBV will be used interchangeably to encompass the specific context of violence that occurs in intimate partner relationships.

Methodology

To answer the research question, we employed Hilary Arksey and Lisa O'Marlley's (2005:22-23) six-stage method proposed for conducting scoping studies. These include: (1) identifying the research question(s); (2) identifying relevant studies through a comprehensive search strategy; (3) study selection based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) data charting by extracting relevant information from the selected studies; (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results; and finally (6) consultation. A scoping study is a systematic process that aims to map the existing research field to assess the depth and breadth of studies carried out in a particular field (Arksey & O'Marlley 2005:21-22). It may include both published and unpublished (grey) literature such as reports, dissertations, newspapers, conference papers, etc. (Levac, Colquhoun & O'Brien 2010:1). We henceforth provide a detailed description of the steps taken to collate findings.

The search context

The context of the study is SSA. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 49 countries fall within the SSA. They include Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cabo Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (the Republic of), Cote d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Lesotho, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra-Leone, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Source of information

The first phase of the literature search was conducted on 11 September 2021, in nine databases and academic search engines. These include the Journal of Religion in Africa, Oria, Journal of Aggression, Journal of Pastoral Care, Scopus, Atla Religion database, Socindex, Google Scholar and the last in SUNScholar Research Repository on 16 July 2022. The second phase of the literature search was again conducted in all the aforementioned sources for current and updated literature on the topic from 14 January 2024 to 23 January 2024.

Both phases of the literature search involved electronic and manual searches. The electronic searches were conducted using the nine databases and search engines. Manual searches were also performed in bibliographies to identify additional relevant books, book chapters, articles, conference proceedings and unpublished dissertations.

After completing stages 1-5, we consulted with four practitioners and experts who consisted of pastors, leaders of CFBOs and social activists against IPV. They were presented with the results and asked these three questions, the responses of which were analysed and written out by both authors: (1) What are the most important results of the scoping review according to your evaluation? (2) What perspectives and publications are you missing in the scoping review? (3) In your view, how should the article conclude?

Search strategy and selection

The initial search terms included: 'intimate partner violence' OR 'gender-based violence' OR 'domestic violence' AND Christian communi* OR faith-based organi* AND 'Sub-Saharan Africa' OR 'West Africa' AND 'interventions' OR 'response' OR 'proactive' OR 'reactive' AND 'women'. This was later refined to include:

religion, faith-based organisations, faith communities, intimate partner violence, gender-based violence, violence against women, interventions, Africa. The search was filtered to include academic literature in English, published in open access journals, peer-reviewed articles, book chapters and dissertations, published between 2000 and early 2024. The searches were reiteratively carried out to ensure rigour and took almost 8 weeks altogether.

The criteria for inclusion were accessible studies, that:

-

Are published in English between 2010 and 2024 within or about SSA.

-

Focus on Christian and interfaith work involving Christian actors.

-

Are multi-country case studies (involving at least one SSA country).

-

Related to churches' reactive and/or proactive measures addressing IPV that mention Christian faith communities' work with IPV.

-

Evaluated church programmes or interventions addressing IPV.

-

Mention perceptions of Christian clergy on IPV and/or GBV.

-

Studied church responses to IPV that develop intervention models.

-

Present theological or conceptual reflections on IPV related to Christian faith communities.

Publications were not included in the review if they:

-

Were published before 2010.

-

Were published in other languages than English.

-

Did not address the issue of IPV.

-

Studied child abuse.

-

Studied exclusively material collected outside SSA or exclusively referred to contexts outside SSA.

-

Studied IPV without any connection to Christian faith communities.

-

Mention FBOs but do not specify which.

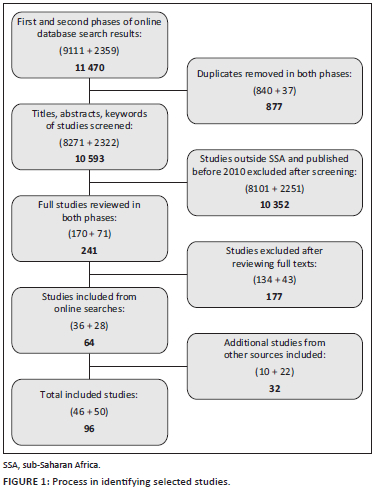

In the first phase of the literature search, a total of 9111 hits were obtained from all electronic databases. After removing 840 duplicates, the remaining 8271 studies were retrieved for screening. This screening process involved evaluating the titles, abstracts and keywords of the studies. During the screening process, 8101 studies conducted outside SSA and published before 2010 were excluded, remaining 170 studies. Both authors independently reviewed the introductions, methods, findings and conclusions of these studies, out of which 134 studies were excluded because they mentioned girls' abuse and had no direct connection to Christian communities. The total remaining studies were 36.

In addition to the electronic searches, 10 additional studies were from other sources. Of these 10, six were identified through manual searching of bibliographies, while four were obtained from hard copies: two from an edited book obtained from the Study of Religions Department of the University of Ghana, one PhD and one master. These were managed with Endnote and folders. The full texts of a total number of 46 studies were finally included in the first phase of the search.

In the second phase of the literature search, a total of 2359 hits were obtained in the same electronic databases between 2021 to early 2024. A total of 37 duplicates were identified and removed. After screening the titles, abstracts, keywords and subjects of 2322 studies, 2251 studies that did not meet the established criteria were subsequently excluded, remaining 71 studies. The full text of these studies was thoroughly reviewed by both authors out of which 43 were excluded, remaining 28 studies.

Additionally, nine studies manually searched from bibliographies including 13 others obtained from several networks when presenting the paper in research forums (two books, four book chapters, one PhD thesis and six articles) were included, totalling 50 included studies. Overall, a total of 96 included studies were screened multiple times - independently and collectively - by both authors. These selected studies were charted in an Excel file. The process of identifying selected studies in both phases is summarised in Figure 1.

Data analysis

The collected data were analysed across categories of methodology, geography, discipline, temporal distribution and research focus. It was also thematically and semantically analysed to identify and report patterns in relation to the research question (Braun & Clarke 2006:79). During the thematic analysis, some initial themes that were hand-coded and later used as pre-defined codes in NVivo software included: forms of violence, causes of violence and effects of violence, women's responses to violence, churches' responses, CFBOs responses, proposed integrative approaches and proposed collaborative approaches. These initial themes were later refined and re-grouped under the main themes: Understanding IPV: forms, causes and effects; How Christian faith communities contribute to IPV; Challenges of Christian faith communities and how Christian faith communities address IPV. The final theme is feedback from the practice field and practitioners. The themes are presented in order following the ethical consideration, after which we conclude.

Ethical considerations

Studies used for this review were all secondary sources openly accessible to the public from the nine databases. There were no identifiable data or personal information, and therefore, no ethical approval was required for the use of this literature.

However, the study is biased in terms of the choice of databases searched and the exclusion of non-English studies, which may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant studies. Additionally, the focus on studies after 2010 and Christian communities and CFBOs may also have excluded studies examining the topic from other faiths or religions. Therefore, the analysis may be limited in terms of providing a comprehensive understanding of the intersection between IPV and FBOs across different religious contexts. This study, nevertheless, is part of a larger PhD study on IPV and Christian religion in Ghana, which was officially reported to Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT), for data protection services. Also, explicit consent of the stakeholders was orally sought by the first author who contacted them by phone because of the geographical distance. The meeting was not recorded, but both authors took notes.

Description of studies included

Methodological distribution

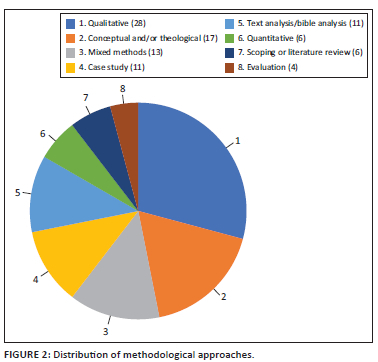

This review analyses the results of 96 pieces of academic work. Figure 2 shows that a variety of different methodological approaches were applied to explore the role of faith communities in addressing IPV in SSA. They range from qualitative methods (28), mixed methods (13), theological and conceptual articles (17) to text analysis and exegetical reflections on Bible texts (11) and case studies (11). Fewer studies have a purely quantitative approach (6). Others can be categorised as evaluations (4). We have also included six literature reviews included a synthesis of six independent and unconnected studies from different parts of the world.

The 11 case studies comprised in the sample either analyse local church communities (Njagi 2017; Palm et al. 2017) or concrete initiatives of FBOs (Petersen 2017; Wamue-Ngare et al. 2023). Some of the studies rather present examples of initiatives that address IPV than critically analyse them (e.g. Parker & Winters 2011). Empirical studies using qualitative methodologies are the largest group in the sample. They are based on ethnographic data collection (Cole 2012), interviews (Le Roux 2014), document analyses or autobiographical narratives (Chisale 2018). Some of the authors are more eager to present their results than explaining their methodological approach (Cole 2012). This makes it sometimes difficult to understand the research design of the studies that the publications document.

The second largest group of studies explores the role of faith and faith communities in relation to IPV with theological and conceptual lenses. They ask, for example, what role pastoral counsellors play when they encounter IPV (Glanville & Dreyer 2013; Nkaabu 2019b) or identify factors related to faith, such as conservative, patriarchal church teachings being preached from the pulpit, that contribute to IPV (Klaasen 2018:4-5; Koepping 2013:264). In the latter case, the authors usually discuss countermeasures (Baloyi 2013:9-10; Dlamini 2022). Several authors trace the legacy of the Circle of Concerned African Women Theologians and highlight its importance for future work against IPV more than 25 years after its establishment (Ayanga 2016; Owusu-Ansah 2016).

The third more substantial cluster highlights the importance of text analyses related to IPV, not at least interpretations of Bible texts. These publications ask for biblical descriptions of the female body against the background of rape (Van Nierkerk 2014) or how single narratives in the Bible can be connected to GBV (Lungu 2016). Other scholars focus on specific Bible texts that need to be re-interpreted in the light of gender justice (Ademiluka 2019, 2021). Several studies point to contextual Bible studies as a suitable method for challenging patriarchal understandings of the Bible on the local level (Mombo & Joziasse 2015; Stiles-Ocran 2023; Torjesen et al. 2019).

Altogether, six studies combine qualitative and quantitative methods - mostly questionnaires as methods for quantitative and different types of interviews as methods for qualitative data collection. These studies often have a closer look into specific regions within one country (Dibie & Okere 2015; Le Roux 2013; Njagi 2017; Wrigley-Asante 2012). Six studies are purely quantitative. Within the framework of a master thesis, one of them asks, for instance, for attitudes and values in relation to rape and sexual coercion in one diocese in one church in South Africa (Okwuosa 2012). Others ask if a change in gender values communicated by church leaders can reduce GBV in families (Warren et al. 2023) or how professionals and practitioners in services for domestic violence survivors evaluate the role of spirituality in their work (Pandya 2017). Six studies produce new knowledge by analysing earlier studies. One of them conducts a synthesis of various unrelated and practice-based studies in six African countries and Myanmar with the aim to detect what faith communities need to develop their work against GBV (Le Roux et al. 2016). Others are scoping reviews about planned or actual activities of faith-based actors against GBV (Le Roux & Du Toit 2017), about war and (gender-based) violence (Istratii 2021b), or about possible reasons for overlooking faith and faith actors in fighting GBV (Istratii & Ali 2023; Istratii et al. 2024). Only four studies understand themselves as evaluations. They are often descriptions of projects and programmes written by insiders (Istratii 2022; Torjesen et al. 2019).

Altogether, almost two-thirds of all studies are empirical, while 28 are textual - analytical, theological or conceptual, that is they focus on what society and civil society organisations or, in most cases, churches should do. The majority of the empirical studies are qualitative, often based on small cases or samples. This means that the research in many cases gives a better understanding of the drivers of GBV and in-depth insights into specific initiatives against GBV or services to help the survivors. This points to the potential that faith communities and religious leaders have in the fight against violence.

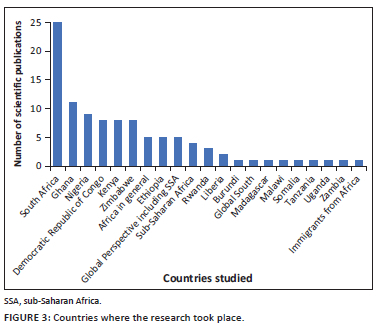

Geographical distribution

Country-wise, six publications refer to Africa in general, five to several SSA countries and one article to the Global South. When it comes to specific countries, 25 studies were conducted in South Africa; 11 in Ghana; nine in Nigeria; eight in the DRC, Kenya and Zimbabwe; five in Ethiopia; three in Rwanda and two in Liberia (Figure 3). One study was found for Madagascar (Cole 2012), Zambia (Lungu 2016), Malawi (Chilongozi 2022), Uganda (Boyer et al. 2022), Somalia (Boeyink et al. 2022), Burundi (Le Roux 2012) and Tanzania (Williams 2018). Several articles examined the situations in several African countries together and with comparative perspectives (e.g. Le Roux et al. 2016; Williams 2018). Two articles presented research on migrant services in Tunisia and the United States of America, respectively, where migrants from various African countries arrived (Pertek 2022; Pertek et al. 2023).

The country overview points thus to a skewed distribution between the countries in SSA. By far most research about the role of Christian faith communities related to IPV is carried out in and about South Africa. That Ghana appears as the country with the second most research studies in this research overview might be explained by the fact that the first author conducts her research in Ghana and had therefore better access to hand-searched literature there. The overview illustrates that there is a huge need for research about IPV and Christian faith communities in many countries of SSA, in particular in the more than 30 countries, for which no studies could be identified.

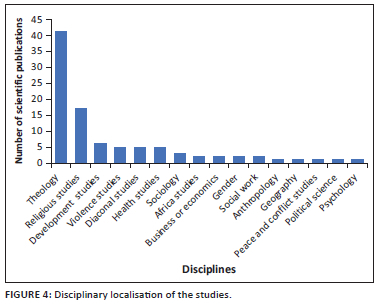

Disciplinary distribution

Not surprisingly, most studies about how Christian faith communities address IPV in SSA are carried out in the field of theology and religious studies. To allocate the disciplinary affiliation of the studies, we had a closer look into the journal or book series in which they were published. Master's and PhD theses were categorised according to the faculties where they were submitted. The diagram (Figure 4) shows that almost half of all research about Christian faith communities and IPV is carried out in theology (42 publications). This explains also the high share of theological, conceptual and text analytical studies. As religious studies (17) and diaconal studies (5) can be considered neighbouring research areas, altogether 64 studies are located in this research field. Among the other studies, there is a huge disciplinary variety ranging from violence studies, development studies and health studies to geography, sociology, psychology, social work, anthropology and economics, gender studies, political science, African studies and peace and conflict studies. In each of these disciplines, only very few scientific studies were located.

The strong representation of theologians in the existing research about Christian faith communities and IPV affects the state of knowledge and choices with regard to research design. Some questions are more likely to be posed, and some themes are more likely to be discussed by theologians than others. More striking is that only about a third of the studies are situating themselves outside the fields of theology, religious studies and diaconal studies. This might indicate that faith and faith communities are not considered to be important for fighting IPV in other disciplinary contexts.

Temporal distribution

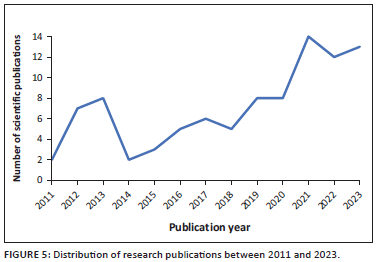

Figure 5 shows that the interest of researchers in the issue of Christian faith communities and IPV has increased considerably during the last decade.

Even though there are some variations between the years, 2013 points itself out as a year in which particular attention was paid to this question. The number of research works in the field is clearly higher in the beginning of the 2020s compared to the early 2010s. From 2020 to 2021, the number increases from 8 to 14 and remains at a high level after this. More than half of the studies (48) are published in the period between 2020 and 2023. The overview in Figure 5 illustrates that the relationship between faith and faith communities and IPV (or fighting it) remains a pressing issue in research.

Research focus

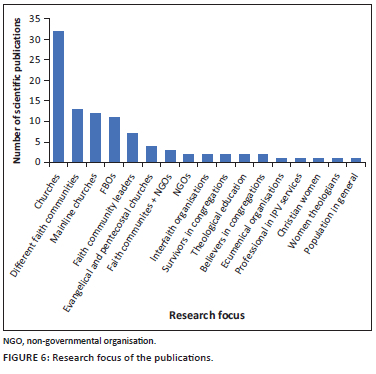

The researchers are primarily theologians, but they are also, in most cases, interested in churches as faith communities that either contribute to IPV or take action against it (see Figure 6). Altogether 33 studies discussed what churches in general do, fail to do or should do. In addition, 12 had a closer look into a certain mainline church or an Evangelical or Pentecostal church. Thirteen studies included faith communities from several religions, often Christian and Muslim communities. Two examined interfaith initiatives and one an ecumenical organisation. Eleven concentrated on specific faith-based organisations (CFBOs), often with social purposes and two on secular civil society organisations (NGOs). Some studies investigated the interplay between faith communities and FBOs (3), respectively, between faith communities and NGOs (2) when responding to IPV. Another field of interest was faith community leaders including ministers, which seven studies paid particular attention to. Only a few studies highlighted theological education (2), survivors in the churches (2), believers in the congregations (2), Christian women (1), female theologians (1), the population in general (1) and professionals in IPV services (1). The research focus shows clearly that most of the research comes from researchers with close connections to the churches that want their churches to become stronger contributors in the fight against IPV.

Even though the topic of Christian faith communities and IPV receives more and more attention in research and the number of published academic works has increased constantly during the past decade, this short overview of the selected research studies shows that the existing knowledge is limited in several perspectives. The empirical studies that are presented in the publications are mostly based on qualitative methods with small samples. They often focus on single church traditions (or single congregations within them). Among them, South Africa has been by far the most prominent research location. Only 17 of the 49 countries of SSA are represented as contexts of research. This may be because of, among possible other reasons, the limitation of our study to studies conducted in the English language, to Christian faith communities and the year range. The authors of the research studies are often theologians with an interest to change the situation for the better both when it comes to the theological understanding of IPV and the local practices. What is missing are more studies with a bird's-eye view, represented by big quantitative studies in several countries in SSA and participatory studies that give voice to the survivors of IPV.

Thematic analysis

Several main themes were derived from the analysis.

Understanding intimate partner violence: Forms, causes and effects

A number of studies utilise different terminologies to refer to IPV. For example, Glanville and Dreyer (2013) and Pietersen (2021) use the term VAW, while Chisale (2018) and others employ DV (Mraji & Rashe 2018; Njagi 2017) and GBV (Msibi 2023; Le Roux et al. 2016; Wamue-Ngare et al. 2023).

Studies maintain that IPV is a pervasive issue perpetrated by men (Kabongo 2021; Klaasen 2018a; Le Roux 2013; Pietersen 2021) and encompasses various forms including physical, sexual, economic and emotional abuse (Le Roux et al. 2020; Magezi & Manzanga 2020; Osei 2011; Parker & Winters 2011). Among the variety of violence, wife beating is the commonest (Baloyi 2013). Studies also show there is a growing concern over sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in some contexts (Boeyink et al. 2022; Le Roux & Bowers-Du Toit 2017).

Intimate partner violence transcends socio-economic and educational boundaries (Uchem 2013), manifesting in the home, church and community (Mombo & Chirongoma 2021). sub-Saharan Africa is notably affected by IPV with a growing impact during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (Magezi & Mangaza 2020). Various scholars propose different conceptualisations of IPV. Some view it as a personal choice by men to assert their dominance over women (Istratii 2020; Klaasen 2018a), and as a result of sin (Gillham 2012), while others consider it as a structural problem stemming from gender norms and socialisation processes that foster patriarchal attitudes (Baloyi 2013; Dlamini 2022; Oguntoyinbo-Atere 2013; Aga 2017; Petersen 2021) or related to depression and other mental health issues that the perpetrators suffer from (Bernardi & Steyn 2020).

Multiple factors contribute to the occurrence of IPV. Cultural practices such as the bride price and beliefs surrounding women's fertility have been associated with IPV (Ademiluka 2021; Ayanga 2016; Baloyi 2013). Additionally, poverty and women's dependence on men along with women's silenced voices have been identified as contributing factors (Baloyi 2013; Williams 2018; Wrigley-Asante 2012). Other explanations include attributing IPV to religious beliefs (Chisale 2018; Koepping 2013; Le Roux 2014; Le Roux & Bowers-Du Toit 2017; Stiles-Ocran 2021a) or to malevolent forces such as the Devil (Marx 2021). In certain contexts, IPV is employed as a political tool against women, regardless of their age, religion or socio-economic status (Nyar & Musango 2013).

The consequences of IPV are profound and encompass a range of physical and psychological effects. Prolonged psychological trauma, post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSDs), HIV or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and mental disorders including death are common outcomes for many women (Ademiluka 2019; Dwamena-Aboagye 2021; Glanville & Dreyer 2013; Okwuosa 2012). These disabling effects have a significant impact on women's functional capacities, representing a public health and development concern (Olusoya 2013). Furthermore, the power dynamics enforced by IPV maintain patriarchal structures, keeping women excluded from decision-making processes and leadership roles, even within religious contexts (Mombo & Joziasse 2015; Van Niekerk 2014; Williams 2018).

How Christian faith communities contribute to intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence is widely associated with religion or faith communities in terms of the dual role of religious organisations, beliefs and practices (Adjei & Mpiani 2022; Istratii & Ali 2023; Pertek et al. 2023). Studies acknowledge the positive and potential role of religion, including Christian churches, in development efforts and in influencing norms and attitudes that promote IPV (Chirongoma 2022; Glanville & Dreyer, 2013; Musodza & Dumba 2015; Njie-Carr et al. 2021; Nkaabu 2019b; Pertek 2022; Shaw et al. 2023; Stiles-Ocran 2020).

However, Christian churches, in particular, play a significant role in perpetuating rather than resolving IPV. Most studies indicate that church responses are often absent or ineffective (Nevhutanda 2019; Stiles-Ocran 2020). Two main ways churches contribute to perpetuating IPV were identified.

Unwillingness and discriminatory attitudes

Several studies highlight that churches, despite their strategic positions in society, often demonstrate a reluctance to engage in efforts to combat GBV (Kabongo 2021; Le Roux et al. 2016). This unwillingness is attributed to patriarchal structures within their institutions (Le Roux 2014), which leads to discriminatory attitudes that render their interventions ineffective (Okwuosa 2012).

Moreover, some studies recognise poverty as a contributing factor to GBV, acknowledging that limited decision-making opportunities for women can perpetuate violence (Van Nierkerk 2024; Williams 2018). Despite awareness of microfinance measures as a means for women's economic empowerment, some churches fail to actively participate in such initiatives (Chilongozi 2022).

Church theologies

The majority of the theological studies focus on the relationship between church theologies and women's experiences of violence. Some studies suggest that church theologies and African women's theologies can be useful in addressing IPV (Owusu-Ansah 2016; Pietersen 2021).

However, church doctrines and sexist theologies that tolerate and perpetuate VAW, including a stronger emphasis on the spiritual rather than social matters, limit church efforts (Dlamini 2022; Glanville & Dreyer 2013; Le Roux 2013; Le Roux & Bowers-Du Toit 2017). Several studies attribute churches' negative responses to gendered biblical misinterpretations and patriarchal theologies and teachings that silence women survivors of sexual violence in order to maintain patriarchy (Adjei & Mpiani 2022; Chisale 2018; Cole 2012; Hlatywayo 2023; Klaasen 2018b; Lungu 2016; Mombo & Chirongozi 2021; Mombo & Joziasse 2012, 2015; Nierkerk 2014; Oguntoyinbo-Ater 2013; Olusoya 2013; Buqa 2022; Freeks 2023; Istratii 2021). Religious programmes such as Christian marriage rituals, often reinforce traditional marriage practices through marriage vows, sermons and literal interpretations of Scripture, which perpetuate men's superiority over women and contribute to GBV (Uchem 2013). The complicit theologies of patriarchal church institutions result in a lack of response to life-threatening IPV situations (Ademiluka 2019; Stiles-Ocran 2020, 2021b).

Challenges of Christian faith communities

The challenges faced by faith communities in addressing IPV vary depending on the denomination and the level of training faith leaders have received (Mahomva et al. 2020). While some Christian churches are actively involved in combating GBV, the majority are not (Magezi & Manzanga 2019). Internal structural issues of division within and between churches and sexual abuse limit churches from collaborating effectively to address IPV (Le Roux 2013). Patriarchy is also widely recognised as a significant influence on church responses and a contributor to IPV (Baloyi 2013; Chisale 2018; Kabongo 2021; Klaasen 2018b; Le Roux 2013, 2014; Le Roux & Bowers-Du Toit 2017; Stiles-Ocran 2021b). However, one study criticises the overemphasis of some studies on patriarchy as the sole explanation for IPV (Bernardi & Steyn 2020). In addition, churches' lack of advocacy and the negative consequences on women's mental health and lives reflect an inadequate understanding and knowledge of the patterns of IPV and the lack of expertise among church leaders (Dwamena-Aboagye 2021; Mahomva et al. 2020).

How Christian faith communities address intimate partner violence

Christian faith communities are important actors in social change and development. Some of the reviewed articles point to the potential that faith communities and their leaders have to affect and change attitudes and behaviours related to IPV. We present what we have learnt from the review about responses of Christian faith communities to IPV. These can be divided into three different types of responses: Specific programmes and initiatives addressing the problem of IPV that Christian faith communities and Christian non-governmental organisations (CFBOs) are involved in; research about the (missed) opportunities of fighting IPV in the everyday practice of faith communities and theological work in the face of the huge problem of IPV in SSA.

Programmes and initiatives

The reviewed articles describe a variety of programmes and initiatives that Christian faith communities have initiated. These include awareness and advocacy work (Cazarin 2019), (pastoral) counselling (e.g. Ezema et al. 2023), and (contextual) Bible work (e.g. Mombo & Jozziase 2015; Torjesen et al. 2019). There are fewer studies about support centres for victims or survivors offering services such as (legal) counselling, medical assistance or financial support (Chirongoma 2021; Osei 2011; Osei et al. 2019; Stiles-Ocran 2021b). While several studies mention economically challenging living conditions as one of the factors contributing to increasing violence in families, there are only very few reported initiatives of faith communities giving women or families the possibility to improve their economic situation, for example through microfinance programmes (Chilongozi 2022; Wrigley-Asante 2012). Much more common are programmes for church leaders who are considered to be key persons to change (theologically legitimised) discriminatory attitudes towards women and to advocate for local action against GBV (e.g. Istratii 2022; Istratii & Ali 2023; Istratii & Kalkum 2023; Nevhutanda 2019; Nkaabu 2019a; Warren et al. 2023). These programmes are not always evaluated as successful.

Some studies point out that the role of leaders is at least ambivalent because some leaders promote conservative and patriarchal values while others embrace progressive values strengthening the role of women (e.g. Palm et al. 2017) or because their commitment is difficult to assess (Stern et al. 2021). Other studies show that programmes are very much needed because religious leaders report that they feel not prepared to act in IPV issues, which they experience as very sensitive (e.g. Mahomva et al. 2020). Some programmes focus on relating IPV to activities strengthening families pointing out that family theology and feminist liberation theology potentially contradict each other and therefore need to be brought together (Petersen 2016, 2017; Shaw et al. 2023). Only one study draws attention to a programme within the framework of Evangelical churches that aims at strengthening the self-esteem of survivors and helping them to handle their experiences with violence spiritually (Marx 2021).

Bible studies that are often described as contextual and take place in local environments are the focus of several research publications. The different ways of conducting these kinds of Bible studies are either presented, evaluated or suggested. The main idea is that patriarchal theological patterns can be revised by working with Bible texts and narratives that teach the equality of all human beings, including women and men (Stiles-Ocran 2023; Torjesen et al. 2019; Wamue-Ngare et al. 2023; Magezi & Manzanga 2021).

Intimate partner violence as a focus area of everyday practice in Christian faith communities

While many studies point out the potential of churches and faith communities when it comes to fighting IPV on the local level, there are only a few examples that describe how this work is effectively included in the everyday routines of the congregations and churches. Exceptions are the programme of the Hillsong church (Marx 2021) or the initiatives in the Anglican church of Kenya (Nkaabu 2023). Studies that investigate the work of church leaders and pastors against IPV rather emphasise that they experience this issue as sensitive and that they express their lack of competence. Consequently, they tend to neglect or avoid questions related to IPV (Mahomva et al. 2020; Mraji & Rashe 2018). The lack of competence of faith leaders is described as both theological (Muthangya 2022; Petersen 2016; Rutoro 2012) and psychological (Nevhutanda 2019). Some researchers claim, therefore, that faith leaders need safe spaces where they can question their own attitudes and learn about tools that they can use when challenging IPV (Palm et al. 2017).

Several studies conclude that personal faith is an asset for survivors when coping with experiences and exploring different alternative actions (Pertek 2022, Pertek et al. 2023; Stiles-Ocran 2023). Even in contexts where women are oppressed and excluded from leadership positions in the church, personal faith can provide survivors with inner strength (Williams 2018). Research about (potential) perpetuators indicates that church teachings are not only used as a justification for exercising VAW but also can be a factor for men to keep away from violence (Turhan 2023). While there is little evidence for collective everyday practices in congregations that hinder IPV, individual religious everyday practices seem nevertheless to be an important resource for coping with IPV and resisting it.

Theological reflection

The reviewed studies refer to comprehensive theological reflection about IPV and the role and task of faith communities. Several theological approaches are presented and sketched to make faith communities more (pro)active in the work against IPV. Some suggest introducing African women's theology at all theological educational institutions (Mombo & Joziasse 2015). Others claim that churches need to work with feminist liberation theology (Jakobsen & Pillay 2022; Lungu 2016; Owusu-Ansah 2016; Petersen 2016). The work with God images is highlighted as an important part of the theological fight against IPV. Violent masculine images of God need to be replaced by female images of a caring God (Msibi 2023). This is a focus area that is also relevant for interfaith work (Warren et al. 2023).

Responsible theology in the face of IPV examines Bible texts that have been used to justify violence (Ademiluka 2019, 2021) and seeks instead to uncover sources of hope in the scripture and church teachings (Mofokeng 2021). It reaches out to the survivors through individual pastoral care (Dwamena-Aboagye 2021; Klaasen 2018a, 2018b) and through being a public caring voice by applying the concept of public pastoral care (Manzanga 2020, Magezi & Manzanga 2019).

Discussions with stakeholders from the practice field

The responses of the stakeholders to the questions we posed underlined that because of Africans' high religiosity, the critical role of religious leaders in Africa and for Africans cannot be ignored and needs to be taken into consideration in IPV-related matters. They emphasised that it is common for many Africans to reach out to their religious leaders when facing challenges, bereavement or trauma including IPV. This means that many religious leaders would know about cases of IPV in their congregations. At the same time, they pointed out that religion plays a double role in these issues, where churches, through leaders, contribute to the prevalence of IPV through their actions and interactions.

These negative church responses were attributed to several factors. Some of the stakeholders perceived that religious leaders lack expert knowledge on IPV, which compromises the capacity of churches to handle cases of abuse. They maintained that psychological approaches and in particular the few mental health-related cases are beyond church theology and the competence of religious leaders. However, the experts also stressed that religious leaders fail to refer survivors to appropriate outfits like clinical support systems, social workers and formal government agencies. At the same time, they consider the services of these formal networks to be deficient in handling issues of IPV. This lack of referral is also attributed both to a lack of knowledge and to the church's efforts to save its public image, especially where religious leaders themselves are perpetrators.

Although all experts agreed that IPV can be solved theologically, they identified church theologies as another problem influencing the way churches respond. Here, they referred particularly to the practice of mediation by church leaders in cases of family conflicts. When religious leaders are engaged in mediation to address violence, it is observed that they are torn between adhering to demands of the Christian faith to uphold the family community and advocating for separation between affected couples when the need arises. Mediations are, instead, often based on limited understandings of biblical texts and theologies that tend to complicate matters for survivors.

Some of the stakeholders argued that apart from the fact that some of these issues were related to individual personalities, they are also connected to one-sided patriarchal interpretations of biblical texts like Ephesians 5:21-22, which are used to overemphasise female submission to men. However, some were quick to add that this cannot be generalised.

In effect, the stakeholders maintained that religious leaders, against the background of their special significance in this matter, need knowledge about the root causes of IPV and to make and take theologically informed decisions and approaches. It is necessary that theological education addresses problems of Bible interpretation concerning IPV and the relationship between women and men. However, they admitted that personal Bible readings and the theological judgement of survivors in challenging dominant biblical narratives should not be underestimated. In addition, they advocated for collaborative efforts between churches, faith leaders and government agencies for referrals and well-informed decisions in their counselling approaches. They underlined, therefore, how important it is that the practices of faith communities rest on research, for example in training manuals for leaders, lay members and survivors.

Conclusion

The scoping review shows on the one hand a rising research interest in the role of faith communities with regard to IPV. It also points to gaps relating to representative, participatory and quantitative studies in SSA. Astonishingly, contextual information about colonialism and post-colonial Africa is seldom highlighted in most studies. What is obvious from the review and consultation with the experts from the field is that faith leaders and communities are actively engaged in, and have the potential to contribute to, the fight against IPV. However, the issue of religion and IPV deserve more attention beyond institutions for theology and religious studies. Therefore, multidisciplinary and well-connected approaches in this research field are needed.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the experts and practitioners from the field who provided them with valuable insights and feedback on the draft article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

E.A.S.-O. was responsible for conceptualising the article, including its design, study selection collation, critical analysis, interpretation and some visuals. E.A.S.-O. wrote the original draft and contributed to subsequent revisions based on feedback received. E.A.S.-O. also authored parts of the final draft and approved A.R.L.-P.'s final inputs before submission. A.R.L.-P. contributed to the review of selected studies, the original draft, design, some visuals and the critical analysis of the selected studies, as well as several drafts of the article. A.R.L.-P. specifically wrote the whole of 'Description of studies included' and 'How Christian faith communities address IPV', and provided comments on other parts of the final draft.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available from the corresponding author, E.A.S.-O., upon reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors. The authors are responsible for this article's results, findings and content.

References

Ademiluka, S.O., 2019, 'Reading 1 Corinthians 7:10-11 in the context of intimate partner violence in Nigeria', Verbum et Ecclesia 40(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v40i1.1926 [ Links ]

Ademiluka, S.O., 2021, 'Patriarchy and marital disharmony amongst Nigerian Christians: Ephesians 5:22-33 as a response', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 77(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v77i4.5991 [ Links ]

Adjei, S.B. & Mpiani, A., 2022, '"I have since repented": Discursive analysis of the role of religion in husband-to-wife abuse in Ghana', Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37(5-6), NP3528-NP3551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520948528 [ Links ]

Aga, A.S., 2017, 'Addressing gender-based violence in Northern Ghana: The role of communication', dissertation, University of Reading. [ Links ]

Arksey, H. & O'Malley, L., 2005, 'Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework', International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 [ Links ]

Asamoah, M.K., 2017, 'The role of the Penteco/Charismatic clergy in the political health development in Ghana', Journal of Religion and Health 56(4), 1397-1418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0354-0 [ Links ]

Ayanga, H.O., 2016, 'Voice of the voiceless: The legacy of the circle of concerned African women theologians', Verbum et Ecclesia 37(2), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v37i2.1580 [ Links ]

Baloyi, M.E., 2013, 'Wife beating amongst Africans as a challenge to pastoral care', In die Skriflig/In Luce Verbi 47(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v47i1.713 [ Links ]

Bazargan-Hejazi, S., Medeiros, S., Mohammadi, R., Lin, J. & Dalal, K., 2013, 'Patterns of intimate partner violence: A study of female victims in Malawi', Journal of Injury and Violence Research 5(1), 38-50. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v5i1.139 [ Links ]

Bernardi, D.A. & Steyn, F., 2020, 'Developing and testing a Christian-based program to address depression, anxiety, and stress in intimate partner violence', Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 40(1), 39-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2020.1828221 [ Links ]

Boeyink, C., Ali-Salad, M.A., Baruti, E.W., Bile, A.S., Falisse, J.-B., Kazamwali, L.M. et al., 2022, 'Pathways to care: IDPs seeking health support and justice for sexual and gender-based violence through social connections in Garowe and Kismayo, Somalia and South Kivu, DRC', Journal of Migration and Health 6, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2022.100129 [ Links ]

Bowers Du Toit, N., 2021, 'Diaconia as public theology within a South African context', in G. Ampony, M. Büscher, B. Hofmann, F. Ngnintedem, D. Solon & D. Werner (eds.), International handbook on Ecumenical Diakonia: Contextual theologies and practices of Diakonia and Christian social services - Resources for study and intercultural learning, pp. 105-110, Regnum, UK. [ Links ]

Boyer, C., Levy Paluck, E., Annan, J., Nevatia, T., Cooper, J., Namubiru, J. et al., 2022, 'Religious leaders can motivate men to cede power and reduce intimate partner violence: Experimental evidence from Uganda', Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(31), e2200262119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200262119 [ Links ]

Braun, V. & Clarke, V., 2006, 'Using thematic analysis in psychology', Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [ Links ]

Buqa, W., 2022, 'Gender-based violence in South Africa: A narrative reflection', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 78(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v78i1.7754 [ Links ]

Carrie, A.M., 2008, New man, new woman, new life, Empower International Ministries, viewed 23 December 2024, from https://empowerinternational.org/articles-guides/resources/. [ Links ]

Cazarin, R., 2019, 'Tactical activism: Religion, emotion, and political engagement in gender transformative interventions', Journal of Religion in Africa 49(3/4), 337-370. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-12340172 [ Links ]

CEDAW, 1979, Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women, New York. [ Links ]

Chilongozi, M.N., 2022, 'Microfinance as a tool for socio-economic empowerment of rural women in northern Malawi: A practical theological reflection', PhD dissertation, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Chirongoma, F., 2021, 'Faith-based interventions in addressing violence against women in Cape Town', PhD dissertation, University of Capetown. [ Links ]

Chirongoma, F., 2022, 'Interfaith approaches to violence against women and development: The case of the South African faith and family institute', in E. Chitando & I.S. Gusha (eds.), Interfaith networks and development: Case studies from Africa, pp. 131-147, Springer, Cham. [ Links ]

Chisale, S.S., 2018, 'Domestic abuse in marriage and self-silencing: Pastoral care in a context of self-silencing', HTS Theological Studies 74(2), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v74i2.4784 [ Links ]

Cole, J., 2012, 'The love of Jesus never disappoints: Reconstituting female personhood in urban Madagascar', Journal of Religion in Africa 42(4), 384-407. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-12341239 [ Links ]

Darteh, E.K.M., Dickson, K.S., Rominski, S.D. & Moyer, C.A., 2021, 'Justification of physical intimate partner violence among men in sub-Saharan Africa: A multinational analysis of demographic and health survey data', Journal of Public Health 29(6), 1433-1441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01260-9 [ Links ]

Dibie, R. & Okere, J.S., 2015 'Government and NGOs performance with respect to women empowerment in Nigeria', Africa's Public Service Delivery & Performance Review 3(1), 92-136. https://doi.org/10.4102/apsdpr.v3i1.77 [ Links ]

Dlamini, N.Z.P., 2022, 'Unmasking Christian women survivor voices against gender-based violence: A pursuit for a feminist liberative pastoral care praxis for married women in the Anglican Church of Southern Africa', PhD dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal. [ Links ]

Dwamena-Aboagye, A., 2021, Ministering to the hurting. Women's mental health and pastoral response in Ghana, UG Press, Accra. [ Links ]

Ezema, J., Diaz, F.J.M., Jaca, M.L.M. & Euwema, M., 2023, 'Pray for improvement: Experiences with mediation of female victims of intimate partner violence in Nigeria', Pastoral Psychology 72(5), 625-646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-023-01101-y [ Links ]

Freeks, F.E., 2023, 'Gender-based violence as a destructive form of warfare against families: A practical theological response', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 79(2), e1-e7. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i2.8969 [ Links ]

Freston, P., 2015, 'Development and religious change in Latin America', in E. Tomalin (ed.), The Routledge handbook of religions and global development, pp. 141-156, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon. [ Links ]

Gathogo, J., 2015, 'Men battering as the new form of domestic violence? A pastoral care perspective from the Kenyan context', HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies 71(3), a2795. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v71i3.2795 [ Links ]

Gillham, S., 2012, 'Combating gender-based violence. The Bible's teaching on gender complementarity', in H.J. Hendriks, E. Mouton, L. Hansen & E.L. Roux (eds.), Men in the pulpit. Women in the pew. Addressing gender inequality in Africa, pp. 93-103, Sun Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Glanville, J.A. & Dreyer, Y., 2013, 'Spousal rape: A challenge for pastoral counsellors', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 69(1), 01-12. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v69i1.1935 [ Links ]

Hlatywayo, A.M., 2023, 'COVID-19 lockdown containment measures and women's sexual and reproductive health in Zimbabwe', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 79(3), a8203. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v79i3.8203 [ Links ]

International Rescue Committee, 2012, Let me not die before my time: domestic violence in West Africa, IRC, NY. [ Links ]

Istratii, R., 2020, 'An ethnographic look into conjugal abuse in Ethiopia: A study from the Orthodox Täwahedo community of Aksum through the local religio-cultural framework', Annales d'Éthiopie 33, 253-300. https://doi.org/10.3406/ethio.2020.1700 [ Links ]

Istratii, R., 2021a, Discourses and practices of Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahәdo clergy regarding faith, marriage and spousal abuse: The case of Aksum in Tigray region (prior the war), SOAS University of London, London. [ Links ]

Istratii, R., 2021b, War and domestic violence: A rapid scoping of the international literature to understand the relationship and to inform responses in the Tigray humanitarian crisis, Working Paper 2 (English), Project dldl/ድልድል: Bridging religious studies, gender & development and public health to address domestic violence in religious communities, London. [ Links ]

Istratii, R., 2022, Training Ethiopian Orthodox clergy to respond to domestic violence in Ethiopia: Programme summary and evaluation report: A Project dldl/ድልድል and EOTC DICAC collaborative programme, Project dldl/ድልድል: Bridging religious studies, gender & development and public health to address domestic violence in religious communities, SOAS University of London, London. [ Links ]

Istratii, R. & Ali, P., 2023, 'A scoping review on the role of religion in the experience of IPV and faith-based responses in community and counseling settings', Journal of Psychology and Theology 51(2), 141-173. https://doi.org/10.1177/00916471221143440 [ Links ]

Istratii, R., Ali, P., Feder, G. & Mshweshwe, L., 2024, 'Integration of religious beliefs and faith-based resources in domestic violence services to migrant and ethnic minority communities: A scoping review', Violence 5(1), 94-122. https://doi.org/10.1177/26330024241246810 [ Links ]

Istratii, R. & Kalkum, B., 2023, Leveraging the potential of religious teachings and grassroots religious teachers and clerics to combat intimate partner violence in international development contexts, Policy brief, SOAS University of London, London. [ Links ]

Jakobsen, W.T. & Pillay, M.N., 2022, 'Re-membering Tutu's liberation theology: Toward gender justice from theo-ethical feminist perspectives', Anglican Theological Review 104(3), 330-340. https://doi.org/10.1177/00033286221079226 [ Links ]

Kabongo, K.T., 2021, 'The fight against gender-based violence: A missional nurturing of people of peace', Verbum et Ecclesia 42(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v42i1.2194 [ Links ]

Kalkum, B., & Istratii, R., 2023, 'Conference proceedings of the project dldl/ድልድል and EMIRTA Annual Conference', Domestic violence-gender-faith: Promoting integrated and decolonial approaches to domestic violence cross-culturally, EMIRTA, UKRI & SOAS Addis, London, Ababa, Ethiopia, 11-12 November 2022. [ Links ]

Klaasen, J., 2018a, 'Intersection of personhood and culture: A narrative approach of pastoral care to gender-based violence', Scriptura 117(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.7833/117-1-1348 [ Links ]

Klaasen, M.A., 2018b, 'A feminist pastoral approach to gender-based violence in intimate partner relationship within marriage', Master thesis, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Koepping, E., 2013, 'Spousal violence among Christians: Taiwan, South Australia and Ghana', Studies in World Christianity 19(3), 252-270. https://doi.org/10.3366/swc.2013.0060 [ Links ]

Le Roux, E., 2012, 'Why sexual violence? The social reality of an absent Church', in H.J. Hendriks, E. Mouton, L. Hansen & E.L. Roux (eds.), Men in the pulpit. Women in the pew. Addressing gender inequality in Africa, pp. 49-60, Sun Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Le Roux, E., 2013, Sexual violence in South Africa and the role of the church, Tearfund, London. [ Links ]

Le Roux, E., 2014, 'The role of African Christian Churches in dealing with sexual violence against women: The case of the democratic republic of Congo, Rwanda and Liberia', Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Le Roux, E. & Bowers-Du Toit, N., 2017, 'Men and women in partnership: Mobilizing faith communities to address gender-based violence', Diaconia 8(1), 23-37. https://doi.org/10.13109/diac.2017.8.1.23 [ Links ]

Le Roux, E., Corboz, J., Scott, N., Sandilands, M., Lele, U.B., Bezzolato, E. et al., 2020, 'Engaging with faith groups to prevent VAWG in conflict-affected communities: Results from two community surveys in the DRC', BMC International Health and Human Rights 20(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-020-00246-8 [ Links ]

Le Roux, E. & Pertek, I.S., 2023, On the significance of religion in violence against women and girls, Routledge, London and New York. [ Links ]

Le Roux, E., Kramm, N., Scott, N., Sandilands, M., Loots, L., Olivier, J. et al., 2016, 'Getting dirty: Working with faith leaders to prevent and respond to gender-based violence', The Review of Faith & International Affairs 14(3), 22-35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2016.1215837 [ Links ]

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H. & O'Brien, K.K., 2010, 'Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology', Implementation Science 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [ Links ]

Lungu, J., 2016, Socio-cultural and gender perspectives in John 7: 53-8: 11: Exegetical reflections in the context of violence against women in Zambia, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Magezi, V. & Manzanga, P., 2019, 'Gender-based violence and efforts to address the phenomenon: Towards a church public pastoral care intervention proposition for community development in Zimbabwe', HTS Theological Studies 75(4), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v75i4.5532 [ Links ]

Magezi, V. & Manzanga, P., 2020, 'COVID-19 and intimate partner violence in Zimbabwe: Towards being church in situations of gender-based violence from a public pastoral care perspective', In die Skriflig / In Luce Verbi 54(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.4102/ids.v54i1.2658 [ Links ]

Magezi, V. & Manzanga, P., 2021, 'A public pastoral assessment of the interplay between "she was created to be inferior" and cultural perceptions of women by Christian men in Zimbabwe as accessory to gender-based violence', Verbum et Ecclesia 42(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v42i1.2139 [ Links ]

Mahomva, S., Bredenkamp, I.M. & Schoeman, W.J., 2020, 'The perceptions of clergy on domestic violence: A perspective from the Kwa-Zulu Natal Midlands', Acta Theologica 40(2), 238-260. https://doi.org/10.18820/23099089/actat.v40i2.13 [ Links ]

Manzanga, P., 2020, 'A public pastoral assessment of Church response to gender based violence (GBV) within the United Baptist Church of Zimbabwe', Doctoral dissertaion, North-West University. [ Links ]

Marshall, K., Roy, S., Seiple, C. & Slim, H., 2021, 'Religious engagement in development: What impact does it have?', Review of Faith & International Affairs 19, 42-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2021.1983347 [ Links ]

Marx, D., 2021, Warrior girls: violence against women and gender-based activism in a Pentecostal-Charismatic church in Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

McPhillips, K. & Page, S.-J., 2021, 'Introduction: Religion, gender and violence', Religion and Gender 11(2), 151-165. https://doi.org/10.1163/18785417-01102001 [ Links ]

Mofokeng, K.T., 2021, 'A pastoral study on gender-based violence and femicide in South Africa', Dissertation, North-West University. [ Links ]

Mombo, E. & Chirongoma, S., 2021, '30 years of African women's liberation theology', In: C. Sophia & M. Esther (eds.), Mother earth, postcolonial and liberation theologies, Lexington Books/Fortress Academic, Maryland. [ Links ]

Mombo, E. & Joziasse, H., 2012, 'From the pew to the pulpit. Engendering the pulpit through teaching "African women's theologies"', in H.J. Hendriks, E. Mouton, L. Hansen & E.L. Roux (eds.), Men in the pulpit. Women in the pew. Addressing gender inequality in Africa, pp. 183-194, Sun Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Mombo, E. & Joziasse, H., 2015, 'Saved but not safe- A parish discussion on the absence of safety in the church: A case study of Kabuku Parish', Interkulturelle Theologie 41(4), 385-399. [ Links ]

Mraji, T. & Rashe, R.Z., 2018, 'Empowerment of women victims of domestic violence in Ntabethemba, Tsolwalana Municipality: An ecclesiastical function of the Evangelical Presbyterian Church of South Africa', Pharos Journal of Theology 99, 1-8. [ Links ]

Msibi, M.C., 2023, 'Facing a masculine God: Towards a pastoral care response in the context of gender-based violence', Master thesis, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Muke, N., 2021, 'Diaconia in traumatised societies. Learning from the Rwandan context', in G. Ampony, M. Büscher, B. Hofmann, F. Ngnintedem, F. Ngnintedem, D. Solon & D. Werner (eds.), International handbook of ecumenical diakonia: Contextual theologies and practices of diakonia and Christian social services - Resources for study and intercultural learning, pp. 456-467, Media Fortress Press, UK. [ Links ]

Murray, R., 2001, 'The African charter on human and peoples' rights 1987-2000: An overview of its progress and problems', African Human Rights Law Journal 1(1), 1-17, viewed 23 December 2024, from https://www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/R21602.pdf. [ Links ]

Musodza, B. & Dumba, O., 2015, 'The church and the management of gender based violence in Mutoko, Zimbabwe', Public Policy and Administration Research 5(10), 124-131. [ Links ]

Muthangya, A.N., 2022, 'The influence of Christian teachings on intimate partner violence (IPV) in Kilifi County, Kenya', PhD thesis, Pwani University. [ Links ]

Nevhutanda, T., 2019, 'Guidelines for support to survivors of intimate partner violence for church leaders in selected Pentecostal churches in South Africa', Doctoral dissertation, North-West University. [ Links ]

Njagi, C.W., 2017, 'The role of faith-based organizations in curbing gender-based violence in Nairobi County, Kenya', PhD dissertation, Masinde Muliro University of science and Technology. [ Links ]

Njie-Carr, V.P.S., Sabri, B., Messing, J.T., Suarez, C., Ward-Lasher, A. et al., 2021, 'Understanding intimate partner violence among immigrant and refugee women: A grounded theory analysis', Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 30(6), 792-810. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2020.1796870 [ Links ]

Njoh, A.J. & Akiwumi, F.A., 2012, 'The impact of religion on women empowerment as a millennium development goal in Africa', Social Indicators Research 107(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9827-4 [ Links ]

Nkaabu, D.M., 2019a, 'Examination of the role of church leaders in averting gender based violence in Imenti South sub county, Meru County, Kenya', Master thesis, Kenya Methodist University (KeMU). [ Links ]

Nkaabu, D.M., 2019b, 'The role of church leaders in averting gender based violence in Imenti South sub-county, Meru County, Kenya', The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies 7(8), 242-247. https://doi.org/10.24940/theijhss/2019/v7/i8/HS1908-062 [ Links ]

Nkaabu, D.M., 2023, 'Role of the Anglican Church of Kenya in averting gender-based violence: A case of diocese of Meru, Kenya', The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies 11(8), 208-270. [ Links ]

Nyar, A. & Musango, J.K., 2013, 'Some insights about gender-based violence in the Gauteng City-Region (GCR)', International Journal of Sociology Study 1(2), 37-45. [ Links ]

Oguntoyinbo-Atere, M.I., 2013, 'The dynamics of power and violence in the interpretaion of 1 Timothy 2:11-15: Case studies of some Nigerian married Christian women', in R.M. Amenga-Etego & M.A. Oduyoye (eds.), Religion and gender-based violence: West African experience, pp. 313-330, Legon Theological Studies Series & Asempa, Accra. [ Links ]

Okwuosa, O.S., 2012, 'Attitudes to sexual coercion and rape within the Anglican Church, Cape Town: A cross sectional survey', Master thesis, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Olusoya, I.A., 2013, 'Misinterpretation of some Christian teachings and traditions as violence against African women', in R.M. Amenga-Etego & M.A. Oduyoye (eds.), Religion and gender-based violence: West African perspective, pp. 284-301, Legon Theological Studies Series, Accra. [ Links ]

Omenyo, C.N., 2006, 'A comparative analysis of the development intervention of Protestant and Charismatic/Pentecostal organisations in Ghana', Swedish Missiological Themes 94(1), 5-22. [ Links ]

Osei, B.K., 2011, 'Role of non-governmental organisations in mitigating gender based violence in Ghana: A case study of Ark Foundation in Accra metropolis', Master thesis, University of Cape Coast. [ Links ]

Osei, B.K., Ofosu, V.S., Odame, C.O. & Agbanyo, W.B., 2019, 'Gender based violence: Performance appraisal of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Ghana', Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 5(3), 253-259. [ Links ]

Owusu-Ansah, S., 2016, 'The role of circle women in curbing violence against women and girls in Africa', Verbum et Ecclesia 37(2), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4102/ve.v37i2.1594 [ Links ]

Palm, S., Le Roux, E. & Bartelink, B.E., 2017, Case study with Christian Aid as part of the UK Government-funded 'Working effectively with faith leaders to challenge harmful traditional practices, Research report, UKaid, Tearfund & Joint Learning Initiatives on Faith and Local Communities, London. [ Links ]

Pandya, S.P., 2017, 'Practitioners' views on the role of spirituality in working with women victims and survivors of domestic violence', Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 26(8), 825-844. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1311976 [ Links ]

Parker, K. & Winters, A., 2011, 'Until the violence stops: Faith, sexual violence, and peace in the Congo', The Journal of Interreligious Studies 5(5), 32-42. https://irstudies.org/index.php/jirs/article/view/67 [ Links ]

Pertek, S., Block, K., Goodson, L., Hassan, P., Hourani, J. & Phillimore, J., 2023, 'Gender-based violence, religion and forced displacement: Protective and risk factors', Frontiers in Human Dynamics 5, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1058822 [ Links ]

Pertek, S.I., 2022, '"God helped us": Resilience, religion and experiences of gender-based violence and trafficking among African forced migrant women', Social Sciences 11(5), 201. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050201 [ Links ]

Petersen, E., 2016, 'Working with religious leaders and faith communities to advance culturally informed strategies to address violence against women', Agenda 30(3), 50-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/10130950.2016.1251225 [ Links ]

Petersen, E., 2017, SAFFI responding to gender-based violence in a South African context: Documenting the history, theory, methods and training model (2008-2017), South African Faith and Family Institute (SAFFI), Cape Town. [ Links ]

Petersen, E., 2021, 'Divine intervention? Understanding the role of Christian religious belief systems in intervention programmes for men who abuse their intimate partners', PhD dissertation, University of the Western Cape. [ Links ]

Pietersen, D., 2021, 'The relevance of theology and legal policy in South African society in connection with violence against women', Theologia Viatorum 45(1), e1-e7. https://doi.org/10.4102/tv.v45i1.120 [ Links ]

Rutoro, E., 2012, 'Gender transformation and leadership. On teaching gender in Shona culture', in H.J. Hendriks, E. Mouton, L. Hansen & E.L. Roux (eds.), Men in the pulpit. Women in the pew. Addressing gender inequality in Africa, pp. 159-169, Sun Press, Stellenbosch. [ Links ]

Santhosh, R., 2015, 'Islamic activism and palliative care: An analysis from Kerala, India', in P. Fountain, R. Bush & R.M. Feener (eds.), Religion and the politics of development. Critical perspectives on Asia, pp. 83-103, Palgrave Macmillan, UK. [ Links ]

Sardenberg, C., 2011, What makes domestic violence legislation more effective?, Pathways Policy Paper, Pathways of Women's Empowerment, Brighton. [ Links ]

Shaw, B., Stevanovic-Fenn, N., Gibson, L., Davin, C., Chipanta, N.S.K., Lubin, A.B. et al., 2023, 'Shifting norms in faith communities to reduce intimate partner violence: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in Nigeria', Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38(19-20), 10865-10899. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605231176799 [ Links ]

Stern, E., Heise, L. & Cislaghi, B., 2021, 'Lessons learnt from engaging opinion leaders to address intimate partner violence in Rwanda', Development in Practice 31(2), 185-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1832046 [ Links ]

Stiles-Ocran, D., 2021a, 'Constructing a heterotopic Christian social practice in Ghana', PhD dissertation, University of Oslo. [ Links ]

Stiles-Ocran, E., 2021b, 'Women's stolen voices in marriage in Ghana: The role of gender, culture, and religion in intimate partner violence', Diaconia. Journal for the Study of Christian Social Practice 12(2), 179-197. https://doi.org/10.13109/diac.2021.12.2.179 [ Links ]

Stiles-Ocran, E.A., 2020, 'No way out? The dilemma of survivors of domestic violence and the church's response in Ghana', Master thesis, VID Specialized University. [ Links ]

Stiles-Ocran, E.A., 2023, 'Theology and women's agency in the context of intimate partner violence in Ghana', African Journal of Gender and Religion 29(1), 74-101. https://doi.org/10.36615/ajgr.v29i1.2423 [ Links ]

Swart, E., 2012, 'Gender-based violence in a Kenyan slum: Creating local, woman-centered interventions', Journal of Social Service Research 38(4), 427-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2012.676022 [ Links ]

Taliep, N., Lazarus, S., Cochrane, J., Olivier, J., Bulbulia, S., Seedat, M. et al., 2023, 'Community asset mapping as an action research strategy for developing an interpersonal violence prevention programme in South Africa', Action Research 21(2), 175-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750319898236 [ Links ]

Tirri, K. & Quinn, B., 2010, 'Exploring the role of religion and spirituality in the development of purpose: Case studies of purposeful youth', British Journal of Religious Education 32(3), 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2010.498607 [ Links ]

Torjesen, K., Ngare, G. & Warren, A.M., 2019, The Tamar campaign: Engine of social transformation. Assessing the Tamar campaign in the DRC, viewed 23 December 2024, from https://www.kirken.no/globalassets/bispedommer/hamar/dokumenter/tamar-kampanjen-rapport.pdf. [ Links ]

Turhan, Z., 2023, 'The role of religion and faith on behavioral change among perpetrators of domestic violence in interventions: A literature review', Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought 42(1), 111-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2022.2144587 [ Links ]

Uchem, R., 2013, 'Eradicating gender-based violence against women in West African Christian societies: Educational imperatives', in R.M. Amenga-Etego & M.A. Oduyoye (eds.), Religion and gender-based violence: West African experience, pp. 265-283, Legon Theological Studies Series, Accra. [ Links ]

UN Women, 2013, Ending violence against women and girls: Programming essentials, UN Women, NY. [ Links ]

UNAIDS, 2014, The gap report. Joint United Nations Program on HIV and AIDS, UNAIDS, viewed 15 October 2021, from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/20140716_UNAIDS_gap_report. [ Links ]

Vähäkangas, A., Hankela, E., Le Roux, E. & Orsmond, E., 2022, 'Faith-based organisations and organised religion in South Africa and the Nordic countries', in I. Swart, A. Vähäkangas, M. Rabe & A. Leis-Peters (eds.), Stuck in the margins? Young people and faith-based organisations in South African and Nordic localities, Research in contemporary religion, vol. 31, pp. 85-95, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen. [ Links ]

Van Niekerk, M., 2014, 'Bodies in the body of Christ: In search of a theological response to rape', Master's in theology, Stellenbosch University. [ Links ]

Wamue-Ngare, G.N., Warren, M.A. & Torjesen, K.J., 2023, 'Combating gender-based violence and fostering women's well-being: Religion as a tool for achieving sustainable development goals in Congo', in Research anthology on modern violence and its impact on society, pp. 1147-1163, IGI Global, Hershey, PA. [ Links ]

Warren, M.A., Torjesen, K., Wamue-Ngare, G., Warren, M.T. & Sam, A., 2023, When religious leaders champion gender equity and religion is a strength: Empowering women and men to collectively mitigate gender-based violence, Center for Open Science, https://dx.doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/3s9j4 [ Links ]

Watlington, C.G. & Murphy, C.M., 2006, 'The roles of religion and spirituality among African American survivors of domestic violence', Journal of Clinical Psychology 62(7), 837-857. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20268 [ Links ]