Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

HTS Theological Studies

On-line version ISSN 2072-8050Print version ISSN 0259-9422

Herv. teol. stud. vol.81 n.1 Pretoria 2025

https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v81i1.10173

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Pentecostal church leaders' support to children in need of care and protection

Andrew SpaumerI; Azwihangwisi H. Mavhandu-MudzusiII

IDepartment of Social Work, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Tshwane, South Africa

IIDepartment of Health Studies, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Tshwane, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Churches are considered one of the important structures responsible for providing care and support to vulnerable populations. One such population are children in need of care and support. This article presents the support provided by Pentecostal religious leaders to children needing care and protection. The study was conducted in Pentecostal churches in Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality, which is found in Gauteng province, South Africa. This qualitative study used an interpretative phenomenological analysis design. Data were collected from nineteen purposively selected leaders in Pentecostal churches using face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Data analysis was guided by the interpretative phenomenological analysis framework for data analysis. Findings indicate that religious leaders within Pentecostal churches are involved in providing care and support to children in need of care. The process they are engaged in include proper identification of those children, attending to physical, psychosocial and spiritual needs. However, each religious leaders use their approach depending on the relationship they have with members of government institutions such as police services and social workers. In order to enhance the support provided the children in need of care and protection, by religious leaders within Pentecostal churches, it is recommended that religious leaders are well informed about the role of different members of multidisciplinary teams such as social workers, psychologists, police officers, parents and other community structures. Moreover, there should be formalised collaboration and referral processes that will ensure that the child's rights are not further violated in the process of provision of support.

CONTRIBUTION: The study contributes to the body of knowledge regarding the role Pentecostal church religious leaders are playing in child protection. Furthermore, it sheds light on the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to ensure that children in need of care and protection are holistically supported.

Keywords: care and protection; children; interpretative phenomenological analysis; Pentecostal church; religious leaders; support.

Introduction

Background

This article presents support provided by Pentecostal churches' religious leaders to children needing care and protection. Children in need of care and protection are those at risk of abuse or neglect whose basic interests, for safety, nurturing and love, are not being met, warranting intervention (Federle 2017). These children often require institutional or alternative care solutions. The Republic of South African (2006) defines what constitutes a child in need of care and protection, including children who have experienced abandonment or orphanhood, exhibit uncontrollable behaviour, reside or labour on the streets, struggle with addiction, encounter situations that could jeopardise their physical, mental, or social health, and endure neglect or maltreatment, abuse, deliberate neglect or degradation at the hands of a parent, caregiver, family member, or individual under their authority.

Violence against children is a significant public health, human rights and social issue with severe consequences for individuals and society (Liel et al. 2020). Neglecting child protection can lead to long-term health issues such as depression, anxiety, substance use, suicide attempts and sexually transmitted infections (Hillis et al. 2016). In order to address this issue, it is crucial to identify and reduce risk factors responsible for dysfunctional, abusive and neglectful parenting (Deva 2024). Child protection mechanisms ensure the overall well-being and development of children, shielding them from exploitation and adversity (Moroz, Bondar & Khatnuik 2023). The South African government, as a signatory to international agreements like the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, bears the obligation to ensure the protection of every child (September 2014). The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 16 on peace, justice and strong institutions, provide a comprehensive framework for enhancing global child protection and promoting the rights of children (Nhapi & Mathende 2021). They work in conjunction with current legislative frameworks and policies to strengthen child protection efforts. The National Child-Care and Protection Policy (NCCPP 2019) in South Africa promotes active stakeholder engagement through inter-sectoral cooperation and community involvement to foster a comprehensive approach to child protection.

The duty of care and protection for children in need should involve initiative-taking, preventive and reactive protective services and assistance (Petty & Mabetoa 2019). Developmental childcare and protection should encompass a comprehensive range of care, assistance and protection measures to promote their welfare, growth and optimal development (NCCPP 2019). These services should be provided by all individuals and organisations responsible for children's well-being, development and protection. The NCCPP (2019) emphasises the importance of effective and high-quality programmes and services in the developmental childcare and protection system. Effective interventions and methods are crucial in working with children, families and communities to address challenges, prevent further harm and enable families to regain shared responsibilities (Petty & Mabetoa 2019).

Religion plays a vital role in the community by fostering support, hospitality and advocacy, which are crucial elements in supporting children in need of care and protection (McLeigh & Taylor 2019). Faith significantly influences norms and practices related to the care of vulnerable children, as religious beliefs often guide moral frameworks and support systems (Ware & Clarke 2016). We cannot exclude religion from providing care and support for children in need, as it fosters community values and social structures, thereby promoting support systems and outreach programmes that aim to empower at-risk families and children in need of care and protection.

However, religion is not static but continuously evolves, or people continuously come up with their own views of religion, which may also have different roles in care and support to children in need of care. One such evolution led to the birth of Pentecostalism. Pentecostalism in Africa has risen significantly due to its responsiveness to local socio-economic challenges, filling gaps left by mission Christianity and drawing from indigenous prophetic traditions (Ng'etich 2023). The rise of Pentecostalism reflects a shift towards social transformation, integrating theology with development and political engagement (Adadey & Barnabas 2024). Gukurume (2024) further highlights the movement's expansion, influence, and participation in community development, recognising it as an undeniable force in development discourse and practice. Pentecostal churches play a vital role in the community by fostering support, hospitality and advocacy, which are crucial elements in supporting children in need of care and protection (McLeigh & Taylor 2019).

Pentecostal church leaders or religious leaders (the term will be used interchangeably with religious leaders) have significantly shaped community values and social structures by establishing institutions such as orphanages, which emphasise love and care for children in need of care and protection. Diaconu et al. (2022) report that these institutions play a crucial role in shaping child protection practices and mobilising community resources to support children in need of care and protection. In Malawi, religious leaders actively engage their congregations and communities in child protection efforts, tackling issues such as child marriage and abuse (Eyber et al. 2018).

In their capacities as leaders of their congregations, religious leaders as respected members of the community are better placed to mobilise community resources and support for children by fostering critical awareness, providing meaningful roles, and facilitating access to spiritual, economic, and human resources (Mobalen, Samaran & Situmorang 2023). Religious leaders play a crucial role in the community, and their influence and role within it significantly contribute to the protection of children in need of care. The purpose of this article is to provide an understanding of the nature of support provided by religious leaders within Pentecostal churches to children in need of care and protection. Understanding the support religious leaders within the Pentecostal Churches provide to children in need of care and protection will shed light on how they operate to foster collaboration with other stakeholders involved in child welfare.

Religious institutions such as the Pentecostal Church are recognised for their promotion of virtues that shape the moral reasoning and behaviour of their members, a crucial aspect of supporting children in need of care and protection (Dermawan 2023). Church members with such virtues can enhance children's well-being and development when involved in child protection programmes (Mukhlis, Muammar & Khatnuik 2024). This can be achieved by considering them as local resources that can reinforce family bonds and fostering a nurturing atmosphere through culturally appropriate interventions in support of children in need of care and protection. The involvement of community organisations in child protection programmes should include the allocation of resources, trainings and public funds to improve their effectiveness. Religious leaders and their institutions are willing to use their resources to protect children in need but training them on child protection matters allows them to engage in activities that promote the safety and well-being of children and families within their communities (Diaconu et al. 2022).

Religious leaders play a crucial role in supporting children in need of care and protection by providing resources, support and opportunities (McLeigh & Taylor 2019). They are better equipped to prevent and respond to violence against children using their religious doctrine, practices and institutional framework. Church members are encouraged to take on the role of caring for children in need of care and protection, moving from institutional care to family-based to community-oriented care models (McLeigh & Taylor 2019). Religious institutions are critical in providing family-based or community-oriented care as they serve as strong motivation for carers, introduce individuals to caregiving roles, and support them in their work (Eagle et al. 2019). Despite a history of abuse within churches, there has been a shift in focus towards listening to victims, providing education for prevention, offering care, designing appropriate sanctions and envisioning restoration (Palm & Eyber 2019).

Religious leaders, who hold significant authority within their congregations, play a crucial role in child protection efforts (Diaconu et al. 2022). Their teachings and authority allow them to educate church members and communities on providing care and support to vulnerable children. Their involvement within the church and community enhances efforts towards child protection, strengthening church teachings and preventing violence against children (Mamonto & Widodo 2022). Religious leaders often receive support from their spouses in dealing with child protection concerns and confronting harmful practices like corporal punishment and early marriage (Eyber & Jailobaeva 2020). However, their lack of expertise can lead to a separation with multidisciplinary teams working on child protection, potentially hindering collaboration efforts (Alexander & Letovaltseva 2023). Additionally, religious leaders often experience the emotional burden of constant exposure to crises, which can negatively impact their emotional well-being due to their occupation.

Religious leaders working with children in need of care and protection must undergo comprehensive training to provide spiritual and emotional support (Mathwasa 2019). Child abuse and neglect can have a lifelong impact on the child, and religious leaders should consult with abuse experts, screen child workers and supervise children in church settings (Guajardo & Tadros2023). Enhancing religious leaders' understanding of human rights is crucial for improving child-care practices and promoting positive disciplinary methods (Diaconu et al. 2022). A formal support structure is necessary for religious leaders to support children in need, ensuring a holistic and sustainable approach to addressing their needs (Diaconu et al. 2022). Strong formal networks allow religious leaders to leverage their social connections and access resources and emotional support (Lee & Wang 2017). This will help ensure a holistic and sustainable approach to addressing the needs of children in need.

Religious leaders can collaborate with other organisations working on child protection to address challenges like child marriages, school attendance, child labour and sexual abuse (Eyber et al. 2018). This approach enhances community participation and influences attitudes towards child welfare (Eyber & Jailobaeva 2020). It also bridges cultural gaps, fosters mutual learning and creates culturally appropriate mechanisms, leading to peace and harmony. However, mistrust between religious leaders and child protection professionals can have unintended consequences, affecting the support provided to vulnerable children (Eyber & Jailobaeva 2020). Pentecostal churches or similar independent churches make up one-third of the overall population in southern Africa. The following section will go into the theoretical framework used in the article.

Theoretical framework

The study was guided by the social ecological model. The model was considered more relevant to the study as it underscores the interaction of individual, family and broader contextual elements influencing child well-being, emphasising the necessity for focused interventions within the child welfare system (Hindt & Leon 2022). The model is essential for understanding the complexities of child protection by offering a thorough analysis of the diverse aspects affecting the lives of children. Thus, the model emphasises the interrelated domains of influence on children's life, including individual, interpersonal, organisational, community, demographic and public policy levels (Hardy 2023). Moreover, child protection initiatives can be informed by the social ecological model, which considers the child's environment and factors affecting their safety and well-being (Williams & Gassam-Asare 2022). Pentecostal churches and their leaders are important part of the child's social ecological system, and they play an important part in the safety and wellbeing of the children. According to the NCCPP (2019), religious institutions play a crucial role in a child's environment by offering responsive, protective and compassionate care and support. Pentecostal churches play a crucial role in a child's mesosystem, providing spiritual guidance and moral principles that guide both the child and their family members (Koehrsen 2022). They also have the power to shape the upbringing and values of children, helping them face social challenges within the ecological system (Pham, Do & Nikoleava 2021). The model is relevant to understanding and interpreting the support provided by Pentecostal church religious leaders to children in need of care and protection.

Methodology

This qualitative study used an interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) design to understand the care and support provided by religious leaders in Pentecostal churches. The IPA design was considered more relevant as the interpretation of the findings is not only from the researchers, but also how the participants, who in this case are religious leaders, interpret their roles in supporting children in need, using a constructivist paradigm to explore the support provided by participants and their experiences.

Setting and sampling

The study was conducted in Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality, which is situated in Gauteng province, one of South Africa's nine provinces.

The researchers used purposive sampling for religious leaders within Pentecostal churches. For Biographical data for participants please see Online Appendix 1. Participants were 21 years of age and older and had served within the Pentecostal church for more than 6 months. Nineteen religious leaders within Pentecostal churches were composed of sixteen male and three female. Among the participants, two had Grade 12 as their highest level of education, three had diplomas, nine bachelor's degrees, four master's degrees, and one a PhD. At the time of the interview, the research participants were leading their churches and living in the City of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality.

Data collection

The study involved in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted in secure, confidential locations. Moreover, informed consent was obtained from the following explanation of the purpose of the study, risks entailed, and how they can be mitigated, benefits and issues of confidentiality. Participants agreed to audio-recording and jotting of field notes and were given the freedom to withdraw at any time. The interviews with general communication to collect biographical data and to make participants feel at ease. This was followed by the following core question: Kindly share with us the support you provide for children needing care and protection. Probing questions were utilised, accompanied with minimal encouragers and paraphrased narratives to avoid misunderstanding. Data collection was done iteratively with data analysis.

Data analysis

The study involved transcribing audio-recorded interview material into text, and two researchers and an external researcher independently examined the nineteen transcripts using the IPA data analysis methodology (Allan & Eatough 2016). Recurrent data analysis was performed until category saturation was reached. Researchers reviewed the transcript multiple times to familiarise themselves with the data and took notes. They identified nascent themes and aggregated related topics, creating a master table of themes for each transcript. The study then analysed all master tables to identify commonalities and discrepancies, resulting in a singular master table of themes. The discourse culminated in a comprehensive master table.

Measures to ensure rigour

Rigour of the study was established using criteria for ensuring trustworthiness proposed by Lincoln and Guba. The criteria include credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability. Some of the measures followed to meet those criteria were verbatim transcription, independent coding, direct quotations from participants, audio recording of interviews and use of open-ended questions.

Ethical considerations

The study proposal was analysed and accepted by the Department Research and Ethics Committee of the University of South Africa, under the reference number 37360450_CREC_CHS_2022, thereby obtaining ethical clearance. The researcher ensured compliance with the following ethical principles: Getting participants' informed written consent, ensuring their voluntary participation, protecting their anonymity, privacy, and confidentiality, and upholding scientific integrity. The study had the potential danger of subjecting participants to emotional distress by eliciting past sensitive experiences during interviews. We averted this by implementing certain therapeutic techniques, such as empathic listening. Participants who required counselling were provided with the service of a counsellor following the interview.

Results

The study centred on the question: What are religious leaders within Pentecostal churches doing to support children in need of care and protection? The results are conveyed using demographic data, which is derived from the study questions and then categorised as themes and subthemes. The themes and subthemes from the study are discussed below.

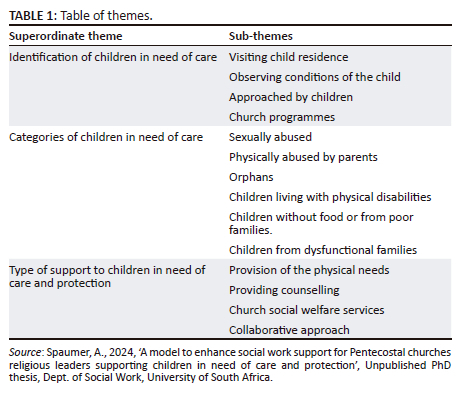

This section provides the results according to themes and subthemes that emerged from data analysis. Each theme is comprised of various sub-themes as indicated in Table 1.

Each sub-theme is supported with a quotation from participants. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality pseudonyms are used in identifying the sources of quotations. The themes are: (1) Identification of children in need of care, (2) Classification Categories of children in need of care, and (3) Types of support provided in need of care and protection.

The discussion of study findings will focus on the approaches that religious leaders within Pentecostal churches use to provide support to children needing care and protection, as described in the next section.

Identification of children in need of care and protection

This theme provides ways in which religious leaders within Pentecostal churches identify children in need of care and protection. The superordinate theme encompasses two themes: direct and indirect methods for identifying children in need of care and protection. Below, we discuss the two themes along with their respective subthemes. Pentecostal churches religious leaders use direct method to identify children who need care and protection. This involves personally visiting the children's homes and carefully evaluating their living conditions, which will be further elaborated upon in the next section.

Visiting child residence

Home visits are crucial for child protection initiatives as they allow professionals to assess the safety and well-being of children in their homes. Results indicate that pastors identify children in need of care and protection through visiting their homes as indicated by the following quote:

'One of the things that we are doing now is to make sure that on a weekly basis, we will at least visit one family, whether they are in church or not and that is where we end up identifying children in need of care and protection.' (Ps Joseph)

The study's findings show that religious leaders within Pentecostal churches use visits to the children's homes to determine both the child's and the family's needs, helping them to provide proper intervention for children identified as being in need of care and protection. The results are in line with the findings of Gubbels et al. (2021), who indicated that pastors' home visits provide church members with special attention, leading to proper intervention for families. This study is in line with Nwaomah and Dube (2018), who indicated that home visits also help religious leaders understand the family's microsystem and the level of social support in the neighbourhood at the exo-system level. This study supports the findings that visiting children's residences provides knowledge about the child's living conditions and leads to proper intervention.

Observing conditions of the child

During the church services and while pastors are interacting with children, they observe children in need of care and protection as stated below:

'I will take that child to their parents to request permission to help the child, as we have observed that they repeat the same clothes each time they come to church….' (Ps Willem)

The findings of this study show that through observing the children attending church services or church programmes religious leaders within Pentecostal churches are able to identify children in need of care and protection. The findings of this study are in line with Murray (2018), who indicated that religious traditions have a long and extensive history of actively engaging with children in terms of their care and education, making them able to observe the conditions of children in their care and in the community who might be in need of care and protection. This is further supported by Palm and Eyber (2019), who indicated that by observing families and children, religious leaders can efficiently identify children who require care and protection.

Pentecostal religious leaders have established connections with parents and children who participate in their church and related programmes. This allows them to identify children in need of care and protection. The research participants expressed this concept through the following statements:

'Within our children's church program, which is where my wife comes in because she works with the children. She is able identify behavioural patterns, abnormal behaviour, and the aggressiveness that comes up within the child. In certain instances, children's isolation is extreme. That is how she can identify that there is a need here; there is a special need there.' (Ps Gabriel)

The study reveals that Pentecostal church religious leaders have formed strong relationships with children and parents involved in their programmes, enabling them to identify children in need of care and protection. This enhances the effectiveness of their programmes, as they provide secure and welcoming spaces for children who have experienced abuse, often having extra common spaces for afterschool or homework programmes (McLeigh & Taylor 2019).

Pentecostal churches' religious leaders indirectly identify children in need of care and protection, as children frequently turn to them for assistance and rely on the church's programmes. The details of these methods are well addressed.

Approached by the child

When children need care and protection, they frequently approach religious leaders, leveraging their influential position in the community to cultivate social connections and enhance self-worth. The following statement confirms that children approach religious leaders when in need of care and protection:

'I remember we had two kids that were raised by the uncle, and when he decided to kick them out of the house…they approached me after Sunday church service without a place to sleep.' (Ps Jones)

The study reveals that children in need of care and protection can approach religious leaders for guidance and comfort. Religious leaders hold authority in spiritual matters and can provide inner peace and understanding. Religious institutions significantly influence the trust of the community they guide (Holmes 2021). Pastors in churches uphold moral authority and build trusting relationships with community members (Eyber & Jailobaeva 2020). Churches that foster a nurturing environment where children feel comfortable expressing themselves openly foster trust, allowing them to address delicate subjects and express their need for care and protection, fostering a sense of comfort.

Categories of children in need of care and protection

Religious leaders in Pentecostal churches are tasked with addressing the needs of children categorised based on their social environment. These children include those directly affected by sexual abuse, physical abuse, orphans, and those living with physical needs. They are also categorised based on factors like lack of food, poverty or dysfunctional families. The focus is on providing care and protection for these children within the community where the church is situated. Pentecostal religious leaders have reported instances of sexual and physical abuse of children by parents, orphans and children with physical disabilities. These children are identified as those in need of care and protection, highlighting the need for effective protection measures. We discuss each of these categories in the following order:

Sexually abused children

Religious leaders within Pentecostal churches encounter sexually abused children during their religious duties in the church and communities, deeming these children in need of care and protection. The subsequent statements recount the experiences of religious leaders:

'We had a case of a young girl who was sexually abused by her father. The girl said I have a problem with my father; he is not treating me well. Then I started suspecting what it was about though she was not clear. I called one of the mothers in church to be with the young girl and to dig further. That is when we realised that she was sexually abused.' (Ps Jones)

Physically abused by parents

Pentecostal churches' religious leaders have documented instances of parental child abuse, highlighting the alarming possibility of such abuse towards their own children, despite their role as protectors, and believe that children in need of care have also experienced such mistreatment. According to the research participants below, parents have been known to physically abuse their children:

'For instance, I had a thirteen-year-old approaching one of our leaders and indicating that he was been physically abused by his dad; his dad is going crazy; he is hitting him; what must he do?' (Ps Moraka)

The study reveals that religious leaders are concerned about children being abused by their parents, despite the church's history of advocating for corporal punishment. The research participants revealed concerns about cases of parents physically abusing their children, which can have long-term effects on their physical health, emotional stability and overall development. A correlation has been found between physical punishment and child behaviour disorder, and the potential for physical punishment to enhance susceptibility (Kobulsky et al. 2017).

Orphans

Religious leaders in Pentecostal churches believe that orphans are children who need support due to lack of parental care. These children's unique challenges, characterised by the loss of their parents, are easily identifiable to these leaders, as they are referred to as children in need of care and protection as delineated in the following statements:

'But over the course of your years in ministry, we come across children who are in need of care and protection because they have lost both their parents while others are staying with their grandparents.' (Ps Matome)

These children often live in households led by single parents, elderly grandparents or impoverished relatives and face challenges such as societal stigmatisation, psychological trauma, health issues, insufficient food access, financial deprivation and schooling obstacles (Bryant & Beard 2016). These children are classified as needing care and protection due to the microsystems within the mesosystem, which impact family dynamics and community support networks, ensuring they have access to necessary resources and opportunities.

Children living with physical disabilities

Pentecostal churches religious leaders have classified children living with disabilities as a specific category requiring care and protection. This was captured in the following:

'There are cases where you find that children living with disability are neglected in the family and there are reported cases of abuse on those children.' (Ps Moraka)

Children with disabilities often face neglect from peers during play and social interactions, leading to social isolation and increased vulnerability to negative childhood experiences like physical and sexual abuse. This is due to their restricted autonomy, early age, and dependence on adults or institutions for emotional and social assistance (Palusci 2017). This reliance makes it difficult for them to address abuse cases, seek help or report incidents (Tsangue et al. 2022). Additionally, children with disabilities are at risk of experiencing abuse and neglect if their carers lack the necessary skills and knowledge to identify and address signs of abuse. The social environment that children are exposed to has a profound impact on their physical, cognitive, emotional and social development. Below, we shall examine these aspects within the context of the kinds of children who require care and protection.

Children without food or from poor families

Research participants have reported that their identification of children without food or coming from poor families has necessitated their provision of help, as detailed in the following narrative:

'With the engagement of the Sunday school teachers, they found out that they were the children that were from poor families and without meals. The only meals they had was the one they receive from church.' (Ps Joseph)

'I must say that in the area where we are, the children that we have mostly been dealing with, are children from poor families who goes days without meals because of poverty.' (Ps Eric)

A study by Bywaters et al. (2018) found a strong link between socioeconomic status and child abuse and neglect, especially among low-income families and those without adequate nutrition. Pentecostal religious leaders are working to address these needs by providing support and assistance to children in need of care and protection.

Children from dysfunctional families

The research participants reported that they have recognised children in need of care and protection due to their upbringing in dysfunctional families. Dysfunctional families are marked by substantial disagreements, neglect or abusive conduct, resulting in a setting that inadequately supplies the essential emotional, psychological and physical support required for a child's growth (Clément et al. 2020). The aforementioned viewpoint was similarly apparent in the opinions expressed by the research participants, as demonstrated below:

'Some of them were vulnerable children as you will find that they are coming from dysfunctional families. You will find that in some instances the father is absent, or he is unemployed. There are situations where we found that the parents take their frustration on the family members because of the stress associated with their parental responsibilities.' (Ps Joseph)

The study reveals that children are vulnerable to abuse and neglect due to their social environments, particularly due to the challenges faced by parents. The family environment, including interactions, personal development and the overall functioning of the family unit, is crucial for a child's welfare (Flores, Salum & Manfro 2014). Pentecostal religious leaders often assist children from dysfunctional households, while child protection professionals struggle to involve parents who resist change, hindering their children's well-being (Sudland 2019). The children's microsystem is shaped by family interaction, relationships and the overall functioning of the family unit, which significantly influences their care and protection.

Type of support to children in need of care and protection

The theme discusses the support provided by Pentecostal church leaders to children in need, including physical needs meeting, counselling, referral to other organisations, church social welfare services and multisectoral collaboration.

Provision of physical needs

Research participants said that they implemented feeding plans aimed at providing meals to both children and their families. According to the religious leaders, they collaborated with church members to gather food and clothing for children needing care and protection. The subsequent statements from leaders within the Pentecostal church substantiated this claim:

'We have some feeding scheme that we were doing in the church. Every Sunday they know that they will receive a meal. This has led to those children inviting their friends to come to church.' (Ps Joseph)

By collaborating with businesses and government departments, religious leaders can provide comprehensive care, including physical support, during humanitarian emergencies (Alexander & Letovaltseva 2023).

Providing counselling

One of the support services Pentecostal church religious leaders offer to children in need of care and protection is counselling. The research participants have highlighted the value of professional counsellors which can supplement their biblical counselling. The study reveals that Pentecostal church religious leaders recognise the importance of spiritual and professional counselling in addressing children's needs and their families. Pastoral counselling aims to improve the mental well-being of the person seeking help, promoting positive transformations in their physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual states (Snodgrass 2015). The opinions of the research participants are expressed in the following statements:

'I will bring them here, but I will be aware that they are going for counselling. Remember that we always do our counselling from a biblical perspective, but sometimes it needs professional counselling. We sent them to a counsellor where they will attend sessions. Not only in the cases of rape but also in cases of grief. If someone losses someone they love or relatives we always refer them to professionals.' (Ps Thulani)

It is essential for offering emotional and spiritual support to children who have experienced abuse, trauma or legal conflict, and addressing their emotional and spiritual needs (Lee & Wang 2017). The research participants acknowledge the necessity of counselling and the crucial role of professional counsellors, stating that they should be aware of their role as carers and counsellors.

Church social welfare services

Churches are reported to work with church members who are professionals in their careers to offer social welfare services to children needing care and protection. The research participants sentiments are expressed in the following statements:

'There was a lady in our church who has just completed her Masters in Psychology. She was working at our church office full-time, to providing counselling service through our church social welfare services. It is unfortunate that she had to go do her practical work training.' (Ps Jones)

Social welfare service programmes provide economic and social protection during unemployment, illness, disability and old age, ensuring adequate care for vulnerable members (Pillay 2017). Religious institutions, particularly churches, play a crucial role in meeting the needs of disadvantaged children by offering moral and spiritual support (Power et al. 2017). In South Africa, Christian churches prioritise social justice, particularly for marginalised populations (Pillay 2017). They provide substantial volunteer assistance and have a record of assisting marginalised groups. They are called to serve as catalysts for transformation, particularly in addressing poverty, violence and injustice towards children (Eyber et al. 2018). Social welfare services provide care and safeguarding for these children, while also providing assistance to families, which are integral to the child support system. Overall, these programmes play a vital role in addressing the challenges faced by marginalised populations in South Africa.

Collaborative approach

Collaboration between religious and secular agencies is crucial for optimising resources, knowledge and outreach in child support and protection. Religious organisations improve child support by referring cases to other organisations and fostering multisectoral cooperation. This comprehensive approach will be explored through the use of multi-sector and referencing other organisations.

Religious leaders within Pentecostal churches refer cases of children in need of care and protection to organisations within their communities designated for child-related work. The research participants' sentiments are captured in the following statement:

'We refer children in need of care and protection to government social workers. Unfortunately, their high case load prevents them from attending to some of the cases we refer them to. There is a shortage of social workers to attend to cases of children in need of care and protection with the urgency it deserves.' (Ps Ndivhuwo)

It is crucial for religious leaders to refer cases of abuse and neglect to organisations with expertise in therapy approaches (Vieth 2018). They must have a clear understanding of their obligations and expertise when dealing with children in need, ensuring swift referrals to professionals for a coordinated response within their communities. The research participants emphasised the need of collaborating with other organisations to increase awareness about child protection and enhance services for children needing care and protection. They highlighted the value of collaboration in improving care and protection in the following statement:

'It is important for the organisations involved in child protection to collaborate work together. As the church we observe the important dates in the year, and on those dates, we invite different organisations to come make presentations on matters related to child protection.' (Ps Sewela)

Multisectoral collaboration in child protection provides comprehensive solutions for families, including prevention services, mental health support and legal aid (Pittz & Intindola 2021). It enhances accessibility of these services for marginalised individuals and developmental projects, ensuring successful support for vulnerable individuals. Collaboration across sectors creates comprehensive guidelines for child protection situations, ensuring efficient processes and synchronised responses (Carla, Cunill-Grau & Repetto 2023). This approach can improve child protection outcomes by promoting comprehensive approaches that engage diverse stakeholders and facilitate information exchange and training (Toros, Tart & Falch-Eriksen 2021). By capitalising on the strengths of various sectors, this approach can lead to better outcomes for vulnerable children, thereby enhancing the overall protection of children.

Conclusion

The study reveals that religious leaders within Pentecostal churches use various approaches to support children in need of care and protection. Although child protection is not their main business, they can identify children in need through their interactions with children and community involvement. They can visit families, provide support through church programmes and collaborate with other organisations to meet the needs of these children. They can also identify children from dysfunctional families, those living in poverty, children abused by parents, sexually abused children, and those with physical disabilities.

Religious leaders in Pentecostal churches are responsible for identifying children who have experienced sexual abuse and providing necessary care and protection, as per Section 150(1)(i) of the Children's Act 38 of 2005. Child abuse is a global public health concern causing significant health, psychological and social difficulties for victims. This study underscores the importance of religious leaders in addressing child abuse.

Religious leaders work with church members to address the physical needs of those in need, including those who are physically or mentally neglected. They also collaborate with businesses and government departments to provide for these needs. Church members are encouraged to donate to the food counter, where collected food is distributed to those in need. Pentecostal churches can identify children needing care and protection while also providing for their physical needs, implementing childcare and protection measures, supporting food programmes and ensuring their physical and emotional needs are met.

The study suggests that a partnership between social child welfare practitioners and religious leaders in Pentecostal churches can effectively protect children's welfare and safety. Religious leaders are responsible for reporting instances of child neglect to child welfare organisations, police and social workers, fulfilling their obligation by actively cooperating with these organisations.

Recommendations

Pentecostal church leaders offer support through church initiatives and collaborative approaches, such as providing physical needs, working with other organisations, and having church social welfare services. They also work through multisectoral collaborations to provide support to children in need. The study highlights the importance of religious leaders in child protection and their role in addressing the needs of children in need. By fostering collaboration among religious leaders within Pentecostal churches, social workers can serve as advocates for child protection through various methods, including:

Provide religious leaders in Pentecostal churches with child protection training, including how to report cases of children requiring care and protection to the authorities.

Conduct more awareness campaigns and programmes to educate the church communities about child protection and the value of reporting children needing care to the authorities.

Child protection professionals should facilitate collaboration and partnership with local church leaders and members to improve cooperation and support for children in need of care and protection.

Acknowledgements

This article is partially based on the first author's thesis entitled 'A model to enhance social work support for Pentecostal churches religious leaders supporting children in need of care and protection' towards a PhD in the Department of Social Work, University of South Africa, South Africa, 18 September 2024, with supervisors Prof. R.P. Mbedzi and Prof. A.H. Mavhandu-Mudzusi.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors' contributions

A.S. conceived the presented idea and conducted data collection. A.H.M.-M. verified methods and results. A.S. and A.H.M.-M. discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and are the product of professional research. It does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institution, funder, agency or that of the publisher. The authors are responsible for this article's results, findings and content.

References

Adadey, F.C. & Barnabas, Y., 2024, 'Pentecostalism and current development in West Africa: Reimagining the Pentecostal landscape, politics, and vision', Spiritus: ORU Journal of Theology 9(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.31380/2573-6345.1347 [ Links ]

Alexander, D. & Letovaltseva, T., 2023, 'Psychosocial workers and indigenous religious leaders: An integrated vision for collaboration in humanitarian crisis response', Religions 14(6), 802-802. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14060802 [ Links ]

Allan, R. & Eatough, V., 2016, 'The use of interpretive phenomenological analysis in couple and family therapy research', The Family Journal 24(4), 406-414. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480716662652 [ Links ]

Bryant, M. & Beard, J., 2016, 'Orphans and vulnerable children affected by human immunodeficiency virus in sub-Saharan Africa', Pediatric Clinics of North America 63(1), 131-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2015.08.007 [ Links ]

Bywaters, P., Brady, G., Bunting, L., Daniel, B., Featherstone, B., Jones, C. et al., 2018, 'Inequalities in English child protection practise under austerity: A universal challenge?', Child & Family Social Work 23(1), 53-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12383 [ Links ]

Carla, B., Cunill-Grau, N. & Repetto, F., 2023, 'A Collaborative Approach for Building Comprehensive Social Protection', In K.J. Baehler (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Public Management for Social Policy, pp. 869-879, Oxford Academic, Oxford. [ Links ]

Clément, M.E., Bérubé, A., Goulet, M. & Hélie, S., 2020, 'Family profiles in child neglect cases substantiated by child protection services', Child Indicators Research 13, 433-454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09665-z [ Links ]

Dermawan, A., 2023, 'The role of Pentecostal worship in virtues development', Jurnal Teologi Amreta 7(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i02.15625 [ Links ]

Deva, G., 2024, 'Protecting the future: Upholding child rights in India', International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research 6(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i02.15625 [ Links ]

Diaconu, K., Jailobaeva, K., Jailobaev, T., Eyber, C. & Ager, A., 2022, 'Development of the faith community child protection scale with faith leaders and their spouses in Senegal, Uganda, and Guatemala', Journal of Religion and Health 62(3), 2196-2212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01660-z [ Links ]

Eagle, D.E., Kinghorn, W.A., Parnell, H., Amanya, C., Vann, V., Tzudir, S. et al., 2019, 'Religion and caregiving for orphans and vulnerable children: A qualitative study of caregivers across four religious traditions and five global contexts', Journal of Religion and Health 59(3), 1666-1686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00955-y [ Links ]

Eyber, C. & Jailobaeva, K., 2020, When a child has not made 18 years and you marry her off ... do not bother to invite me! I will not come, pp. 188-203, Routledge eBooks, Milton Park. [ Links ]

Eyber, C., Kachale, B., Shields, T. & Ager, A., 2018, 'The role and experience of local faith leaders in promoting child protection: A case study from Malawi', Intervention Journal of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas 16(1), 31-37 https://doi.org/10.1097/WTF.0000000000000156 [ Links ]

Federle, K.H., 2017, 'Do rights still flow downhill?', The International Journal of Children's Rights 25(2), 273-284. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02502004 [ Links ]

Flores, S.M., Salum, G.A. & Manfro, G.G., 2014, 'Dysfunctional family environments and childhood psychopathology: The role of psychiatric comorbidity', Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy 36(3), 147-151. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2014-0003 [ Links ]

Guajardo, A. & Tadros, E., 2023, 'The long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment for adult survivors: A chronic price to pay', Journal of Psychological Perspective 5(1), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.47679/jopp.515202023 [ Links ]

Gubbels, J., Van Der Put, C.E., Stams, G.J.M., Prinzie, P.J. & Assink, M., 2021, 'Components associated with the effect of home visiting programs on child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review', Child Abuse & Neglect 114, 104981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104981 [ Links ]

Gukurume, S., 2024, 'New Pentecostal urbanities in Harare: Landscapes of everyday life and visions of the future', African Identities 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2024.2381483 [ Links ]

Hardy, A.R., 2023, 'Developing Pentecostal church planting pedagogy that responds to social need and ecological crisis', Journal of Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity 43(2), 170-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/27691616.2023.2227243 [ Links ]

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A. & Kress, H., 2016, 'Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates', Pediatrics 137(3), e20154079. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079 [ Links ]

Hindt, L.A. & Leon, S.C., 2022, 'Ecological disruptions and well-being among children in foster care', American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 92(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000584 [ Links ]

Holmes, S.E., 2021, 'Do contemporary Christian families need the church? Examining the benefits of faith communities from parent and child perspectives', Practical Theology 14(6), 529-542. https://doi.org/10.1080/1756073X.2021.1930698 [ Links ]

Kobulsky, J.M., Kepple, N.J., Holmes, M.R. & Hussey, D.L., 2017, 'Concordance of parent- and child-reported physical abuse following child protective services investigation', Child Maltreatment 22(1), 24-33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559516673156 [ Links ]

Koehrsen, J., 2022, Religion and ecology, pp. 282-294, Edward Elgar Publishing eBooks, Northampton. [ Links ]

Lee, E.K. & Wang, Z., 2017, 'A Computational Framework for Influence Networks: Application to Clergy Influence in HIV/AIDS Outreach', In J. Diesner, E. Ferrari & G. Xu (eds.), Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining Sydney, Springer, 31 July - 3 August, pp. 1175-1182. [ Links ]

Liel, C., Ulrich, S.M., Lorenz, S., Eickhorst, A., Fluke, J. & Walper, S., 2020, 'Risk factors for child abuse, neglect, and exposure to intimate partner violence in early childhood: Findings in a representative cross-sectional sample in Germany', Child Abuse & Neglect 106, 104487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104487 [ Links ]

Mamonto, N.K.M. & Widodo, P., 2022, 'Isu Perlindungan Anak sebagai Bagian Pelayanan Holistik Gereja', IMMANUEL: Jurnal Teologi dan Pendidikan Kristen 3(2), 119-133. https://doi.org/10.46305/im.v3i2.131 [ Links ]

Mathwasa, J., 2019, 'Pastoral care and counselling in early childhood years', In J. Howell, M. Cleveland-Innes, M. Badea, & M. Suditu (eds.), Advances in early childhood and K-12 education, pp. 192-216, IGI Global Scientific Publishing, New York [ Links ]

McLeigh, J.D. & Taylor, D., 2019, 'The role of religious institutions in preventing, eradicating, and mitigating violence against children', Child Abuse & Neglect 110(1), 104313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104313 [ Links ]

Mobalen, O., Samaran, E. & Situmorang, L., 2023, 'Program our empowering the role of religious leaders as renewal agents for community health in the COVID-19 pandemic', Jurnal Kreativitas Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat (PKM) 6(1), 327-340. https://doi.org/10.33024/jkpm.v6i1.8145 [ Links ]

Moroz, O., Bondar, V. & Khatniuk, Y., 2023, 'Protection of children's rights as a component of Ukraine's national security', Socìalʹno-pravovì studìï 6(3), 104-110. https://doi.org/10.32518/sals3.2023.104 [ Links ]

Mukhlis, M., Muammar, M. & Maghfirah, F., 2024, 'Community Involvement in the Establishment of Child Decent Qanun in East Aceh District', In M. Mukhlis, M. Muammar & F. Maghfirah (eds.), Proceedings of Malikussaleh International Conference on Law Legal Studies and Social Science (MICoLLS), Malikussaleh University, Aceh-Indonesia, October 10-11, 2023, pp. 0020-0020. [ Links ]

Murray, J., 2022, 'Any questions? Young children questioning in their early childhood education settings', European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 30(1), 108-130. https://doi:10.1080/1350293X.2022.2026436 [ Links ]

Ng'etich, E.K., 2023, 'Global and local Pentecostal histories: Reframing Pentecostal historiography in Africa', Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae 49(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/12012 [ Links ]

Nhapi, T.G. & Mathende, T.L., 2021, Towards Child-Centred Sustainable Development Goals, pp. 100-127, IGI Global eBooks, Hershey. [ Links ]

Nowell, L.S., Norris, J.M., White, D.E. & Moules, N.J., 2017, 'Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria', International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847 [ Links ]

Nwaomah, E.N. & Dube, S., 2018, 'Pastoral visitation as a veritable tool in strengthening family relationships', Journal of Religious Studies 14, 125-140. [ Links ]

Palm, S. & Eyber, C., 2019, Why faith? Engaging faith mechanisms to end violence against children, Briefing Paper, Ending Violence against Children Hub, Joint Learning Initiative on Faith and Local Communities, Washington, DC, viewed from https://jliflc.com/resources/why-faith-engaging-faith-mechanisms-to-end-violence-against-children/. [ Links ]

Palusci, V.J., 2017, 'Children with disabilities: Prevention of maltreatment', Journal of Alternative Medical Research 9(3), 1-22. [ Links ]

Petty, A. & Mabetoa, M., 2019, Child, youth, family care and related legislations: BSW3704 study guide, University of South Africa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Pham, T.H., Do, L.H. & Nikolaeva, E., 2021, 'Religious ecology in sustainable development in the world and Vietnam', E3S Web of Conferences 258, 05006. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125805006 [ Links ]

Pillay, J., 2017, 'The church as a transformation and change agent', HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies 73(3), a4352. https://doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4352 [ Links ]

Pittz, T.G. & Intindola, M.L., 2021, 'Cross-sector Collaboration', In Scaling Social Innovation Through Cross-sector Social Partnerships: Driving Optimal Performance, pp. 17-27, Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds. [ Links ]

Power, M., Doherty, B., Small, N., Teasdale, S. & Pickett, K.E., 2017, 'All in it together? Community food aid in a multi-ethnic context', Journal of Social Policy 46(3), 447-471. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279417000010 [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA), 2006, Children's Act, 38 of 2005, Government Gazette, vol. 492, Government Printer, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Snodgrass, J., 2015, 'Pastoral counselling: A discipline of unity amid diversity', in E. Maynard & J. Snodgrass (eds.), Understanding Pastoral counselling, pp. 1-15, Springer, New York, NY. [ Links ]

South Africa, 2019, National child-care and protection policy, Government Printers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Spaumer, A., 2024, 'A model to enhance social work support for Pentecostal churches religious leaders supporting children in need of care and protection', Unpublished PhD thesis, Dept. of Social Work, University of South Africa. [ Links ]

Sudland, C., 2019, 'Challenges and dilemmas working with high-conflict families in child protection casework', Child & Family Social Work 25(2), 248-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12680 [ Links ]

Toros, K., Tart, K. & Falch-Eriksen, A., 2021, 'Collaboration of child protective services and early childhood educators: Enhancing the well-being of children in need', Early Childhood Education Journal 49(5), 995-1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01149-y [ Links ]

Tsangue, G.T., Awa, J.C., Nsono, J., Ayima, C.W. & Tih, P.M., 2022, 'Non-disclosure of abuse in children and young adults with disabilities: Reasons and mitigation strategies for the Northwest Region of Cameroon', African Journal of Disability 11, 1025. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v11i0.1025 [ Links ]

Vieth, V.I., 2018, 'Coordinating medical and Pastoral care in cases of child abuse and neglect', Currents in Theology and Mission 45(3), 27-30. [ Links ]

Ware, A. & Clarke, M., 2016, 'Faith and crossing boundaries: implications for development policy and practice', Development Across Faith Boundaries, pp. 183-194, Routledge, Melbourne. [ Links ]

Williams, M.S. & Gassam-Asare, J., 2022, 'The socio-ecological model: A multifaced approach for I-O psychologists to design interventions targeted at reducing police violence', Industrial and Organizational Psychology 15(4), 588-591. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2022.81 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Andrew Spaumer

spauma@unisa.ac.za

Received: 20 Aug. 2024

Accepted: 28 Oct. 2024

Published: 17 Jan. 2025

Note: Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article as Online Appendix 1.