Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.39 n.1 Cape Town Jan. 2013

REVIEW ARTICLES

Fictions of the Liberation Struggle: Ruy Guerra, José Cardoso, Zdravko Velimirovic

Raquel Schefer

Université de la Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3

Ruy Guerra, Mueda, Memória e Massacre (Mueda, Memory and Massacre), 1979, Mozambique, 77 minutes, 16 mm, black and white, Portuguese and Shimakonde.1

Zdravko Velimirović, O Tempo dos Leopardos (Time of the Leopards), 1985, Mozambique and Yugoslavia, 91 min, 35 mm, colour, Portuguese.

José Cardoso, O Vento Sopra do Norte (The Wind Blows from the North), 1987, Mozambique, 101 minutes, 16 mm, black and white, Portuguese.

If you want to know who I am,

examine with careful eyes

that piece of black wood

which an unknown Makonde brother

with inspired hands

carved and worked

in distant lands to the North.2

The birth of cinema

The history of African independence movements might suggest that the birth of a modern country would coincide with the birth of its cinema. As happened during the decolonisation processes of other African countries, such as Algeria, Guinea-Bissau and Angola, cinema played a crucial role during Mozambique's Liberation Struggle (1964-1974). The struggle for independence was fought both on the military-political front and in the cultural field inasmuch as decolonisation was conceived as a political and a cultural process.3 Cinema was then considered a powerful instrument of liberation: a pedagogical tool within Mozambican borders, forging political unity beyond cultural divisions and spreading FRELIMO's4 ideological principles. Cinema also permitted the documentation and dissemination of material and visible evidence of the fight for independence at an international level.5 Mozambican revolutionary cinema might be understood as both an expression and a vehicle of the effort to forge and soon after to consolidate the nation's geographical, political and cultural unity, as well as to implement FRELIMO's socialist project. The struggle for independence and for the effective control of the means and the objects of production was also a struggle to transform the colonial hegemonic cultural forms, fusing art and social praxis,6 and creating a liberated image. In the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts,7 Karl Marx sees in art a prefiguration of the intensified sensibility of men liberated from historical alienation. If art and discursive forms are inseparably connected with the historical forms of society, they would reflect - and even anticipate - the change in infrastructure.8 Aesthetic stances and the realm of sensibility would be refreshed while new forms of representation would emerge. In this frame, Mozambique's cinema and its film language would derive from, be concomitant with, and express the country's political and cultural process. Film images would not only found history and represent the on-going revolutionary process; they would also forecast a utopian future.

Almost forty years after Mozambique's independence in 1975, the country's revolutionary cinema is not only the most complete visual remnant of this historical period; in addition, it must be recognised as an archive of images permeated by dispositifs of power, past vivid elements and ideology, from which might emerge a critical knowledge of FRELIMO's cultural and aesthetic perspective embedded in the modernist alliance between art and politics.

Cinema of liberation was essentially documentary. The first fiction features on the decolonisation process were produced after independence. Foundational events of Mozambican contemporary history were indeed the subject of three feature films, which, although very different formally, might be considered as the first cinematic attempts, in the field of fiction, to stabilise the history and the memory of the decolonisation process. These films are Ruy Guerra's Mueda, Memória e Massacre (1979), Zdravko Velimirović's O Tempo dos Leopardos (1985) and José Cardoso's O Vento Sopra do Norte (1987). Mueda was recently digitised and digitally film-restored in a co-operation between Mozambique's National Institute of Audiovisual and Cinema (INAC), the University of Bayreuth, the University Eduardo Mondlane (Maputo) and the Cultural Institute Mozambique-Germany (ICAM). The result was edited into a DVD by Arcadia Filmproduktion.9 O Vento was restored in 2010 from the 16 mm original negatives by the Portuguese Cinematheque's National Archive of Moving Images (ANIM)10 under the co-operation agreement signed between this institution, the INAC and the Portuguese Institute for Development (IPAD) to restore Mozambican film archives.

Mueda, O Tempo and O Vento propose particular spatiotemporal approaches to the depicted political events. In addition to their common retrospective gaze, their different relation to time is indicative of the several phases of the Mozambican historical process. Ruy Guerra's film, a foundational object in political and cinematic terms, was produced between 1978 and 1979, at the height of INC, the Mozambique's National Institute of Cinema, created in March 1976 as one of the governing party of newly independent Mozambique's first cultural acts.11 By contrast, O Vento was released in 1987, one year after the death of Samora Machel, in a very different political context. Indeed, South Africa and its allies' destabilisation campaign and their support to RENAMO, the Mozambican National Resistance, would lead to a new war (1976-1992) that would undermine Mozambique's economic and political structures. Since 1982, the Government of Mozambique began negotiations to become a member of the IMF, which would happen two years later. In 1987, Mozambique signed an agreement with the World Bank and the IMF to introduce the Economic Rehabilitation Program (ERP). The decline of INC's film production begins at that moment and would culminate in 1991 with a fire that destroyed the Institute's production and editing facilities - although not the archives.12 In 2000, INC became INAC, the current National Institute of Audiovisual and Cinema, where INC's archives, about 25 thousand film boxes, remain today. As for O Tempo dos Leopardos, its conception as an epic film contradicts the formal and aesthetic principles guiding Mueda, the first fiction feature of independent Mozambique, a designation noted on the film's official poster at Guerra's request.13

There is a fundamental gap between the films' diegetic and historical temporalities. Not only do they all deal with past events and correspond and respond to different moments of the Mozambican political and cultural project,14 but also their formal, narrative and aesthetic procedures express, in spite of authorial stylistic characteristics, different horizons of expectation.15

There is a significant trend towards a progressive fictionalisation of the decolonisation process, culminating in the direct representation of the military conflict in O Tempo. Following the production of this film in 1985 and of O Vento two years later, film production began to decline. The production of fiction features even came to a complete stop until recently. The history of fiction film in Mozambique appears therefore to be entangled with the history of the country's revolutionary project.

To alter the image

The Liberation Struggle, conceived as a continuous cultural process, was conducted on two fighting lines: the politico-military line against Portuguese colonialism and, after independence, the destruction or alteration of the colonial structures, a process which was not always unequivocal. Furthermore, on the aesthetic front, breaking the codes inherited from colonialism would result in the emergence of Mozambican aesthetic forms: revolutionary and non-aligned forms; new forms that would conciliate Samora Machel's ideal of modernity and modernisation and the traditional modes of cultural expression, mixing popular motifs and forms with modernist elements.

The effort to build a new Mozambican cultural identity - or rather a new dimension of national cultural identity - starting from a process of interpretation, rereading and renewal of tradition, provided the basis for the creation of cultural structures such as INC. According to the sociologist and former Mozambican Minister of Information, José Luís Cabaço,16 the idea of a dialectical interaction between the new problems caused by the resistance to colonialism and aspects of the cultural tradition was central during Liberation Struggle. These elements' synthesis would give origin to renewed cultural forms, a principle close to Amílcar Cabral's conception that national liberation is necessarily an act of culture.17

Before and after Mozambique's independence, FRELIMO accorded great importance to the cinema as a vehicle for the new country's ideological and material construction.18 During the Liberation Struggle, foreign filmmakers such as Margaret Dickinson19 and Robert van Lierop20 shot images of the uprising that clearly showed FRELIMO's project transcending the frameworks of nationalism and Africanism, entirely reorganising life and changing Mozambican people. This transformation would be developed during the liberation process itself, departing from the rupture with both colonialism and pre-colonial society, which would lead to the ideal of the Homem Novo ('New Man').21

In a country with 90% illiteracy and great linguistic diversity, cinema would soon be conceived by FRELIMO as an instrument to decentralise the place of colonial history within postcolonial Mozambique: it was a way of legitimising not only the socialist state under construction, but also Mozambican identity and cultural specificity, establishing the idea of the nation beyond ethnic multiplicity.

After independence, revolutionary images continued to be produced by INC's technicians and foreign collaborators, as well as by filmmakers like Jean Rouch and Jean-Luc Godard,22 who visited Mozambique between 1977 and 1978 respectively in the context of a training mission of Mozambican technicians and to assist in the founding of the first public television station. Images of rebel and disobedient bodies, young guerrilla fighters from the liberated areas' phalansteries in Franco Cigarini's 10 Giorni con i Guerriglieri nel Mozambico Libero,23 or images of the liberation on 25 June 1975 in José Celso Martinez Corrêa and Celso Luccas' 25 - Vinte e cinco24 were inseparable from the will to create a new film language, to alter the image enabling it to represent the complex dynamics of the birth of a nation, a hypothesis that is reinforced by the presence of filmmakers like Guerra, Godard and Rouch in Mozambique.

From 1976 to 1991, INC produced thirteen documentary and feature films, 119 shorts, and 395 cinema reports (newsreels) titled Kuxa Kanema (Birth of the Image or Birth of Cinema).25 Kuxa Kanema was collectively produced and screened from south to north, even in remote rural areas, where mobile cinema units provided by the Soviet Union would take the film reels and the screening equipment.

There is still an often unconsidered film on Mozambique's decolonisation process. Godard, who was invited to conduct research in order to create Mozambican national television, concluded that video technology - considered to be a non-tropicalised machine26 - would be the most appropriate audiovisual format to create a liberated television production system. Godard's project to introduce video technology to communal villages led to misunderstandings between the filmmaker and his Mozambican hosts. The video essay Changer d'Image - Lettre à la bien aimée27 is undoubtedly the outcome and an object of reflection on the Mozambican experience.

In the first sequence of the film, the filmmaker, while turning his back to the camera and contemplating a blank white screen, from which images are absent, questions himself:

Can an image of change exist? Can an image be qualified to express change, to express the idea of change? Can an image provoke change?28

The question was then how to alter the image in such a way that it could represent and induce change. Today, the pale immaterial images of the insurrection evoke presences and absences. These shreds of Mozambique29 recall a Horla of spectra, the spectra of the bloody and unnecessary war which delayed independence by ten years, as well as the spectra of the failed Mozambican political project, from which INAC's dusty shelves, where most of this extraordinary film corpus is preserved, could be a strong if inconceivable metaphor.

The liberation struggle was an exceptional political process that involved a vast political change, decolonisation and Marxism's implementation, and an attempt to invent Mozambican aesthetic forms, particularly film forms, as a result of the emphasis given to the cinema in Samora Machel's programme. Quoting Alain Badiou, 'the direct dimension of cinema is not incompatible with the direct concern to invent forms in which a country's reality is given as a problem'.30

This article addresses the cinematic representation of Liberation Struggle from a multi-temporal framework. Cinematic representation of political events and historical processes are intertwined in a complex and transversal temporal frame that includes prefiguration, memory and rewriting. Liberation films are then approached as unfixed objects in permanent re-signification.

Analysing the history and the philosophy of science, Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison31 conceive objectivity as a mutable concept, changing in response to epis-temic virtues, which can be diagnosed by looking critically at the visual representation in which they manifest. If this hypothesis points to epistemological ideologies in a Foucauldian way,32 I argue that from the examination of the way historical processes are represented in film objects, as complex discursive formations, effects of knowledge about the ideological features underlying these processes may arise.

A cautious approach is therefore required in analysing historical film objects. It is fundamental to consider presentification and temporal dislocation as inherent processes in the protocols of legibility, and to acknowledge the necessary interference of subjectivity. In this way, there is a dislocation between the films' collective moving images and the solitude of the researcher who seeks to restore the way cinema relates to politics, supported by critical and epistemological instruments.

Mueda, Memória e Massacre

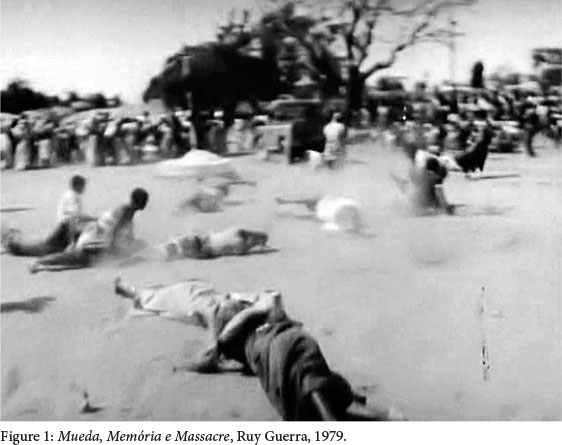

Re-enactment, historical documentary, political fiction, ethnographic film - all those genres are evoked, at first glance, by Mueda, Memória e Massacre. The historical issues at stake in Mueda point to a genealogy of Mozambican cinema interwoven with the country's political project. The founding film of Mozambican cinema, since it launched the formal and expressive conditions of its birth, Mueda would be re-edited without Guerra's direct supervision after being awarded the Prizes 'Film and Culture' and 'People's Friendship Union' at Tashkent Film Festival in 1980.

A close and critical analysis of the film's context of production as well as of its aesthetic, narrative, ideological and thematic features allows us to sketch out a genealogy of Mozambican cinema, and to start developing an archaeology of its fictional forms. Although documentary film would be the dominant form of expression of Mozambican cinema (comprising the country's pre-cinema and the cinematographic production made during the post-revolutionary period), the birth and decline of fiction happens at the same time in which Marxism-Leninism is adopted as the country's official ideology during FRELIMO's Third Congress in 1977 and then abandoned in 1989 in the Fifth Congress.

Mueda, directed by Ruy Guerra, who was born in Lourenco Marques (now Maputo) in 1931, although considered Mozambique's first fiction feature, creates a profound synthesis between cinematographic genres. Guerra, who had lived in Brazil since the 1960s, came back to Maputo at the invitation of INC. At this moment, Guerra had already directed some of his most remarkable works, such as the 1962 Os Cafajestes,33 and the 1964 Os Fuzis.34 Guerra's international reputation as one of Cinema Novo and Latin America's leading cineastes would legitimate Mozambican cinema while his presence in Maputo would mark the birth of national cinema. He participated in the cinematographic foundation of Mozambique not only training technicians at INC, but also cinematographically reconstituting the collective memory of one of the most significant episodes of resistance against Portuguese colonialism, the Mueda Massacre, the subject of Mueda. Guerra was also involved in the failed project of taking cinema to communal villages, a project similar to Godard's intended program, except that it only involved the reception of moving images and not their production by the population.

On 16 June 1960, the Mueda Massacre took place in the Makonde Plateau, in Northern Mozambique. The Portuguese colonial administration repressed a peaceful demonstration for the improvement of work and life conditions and eventually independence, murdering more than 600 people according to official Mozambican history. The circumstances surrounding the massacre are still ambiguous today, particularly regarding the number of victims. The Mueda Massacre considerably contributed to the Makonde people's politicisation, influencing FRELIMO's development and its military campaign.35 In fact, it was precisely on the Makonde Plateau that the first liberated areas36 were established. From this point of view, Guerras film would not just commemorate one of the main symbolic antecedents of the Liberation Struggle and FRELIMO's foundation, but it would also - and above all - create and historically inscribe the film memory of the historical event, given the absence of archive images.

Guerra chooses to shoot an oral and improvised play, never set down in writing, in which Mueda's people incarnated simultaneously the colonial administration's characters and the demonstrators. The film intercuts images from this mise en scène with documentary interviews with survivors and witnesses of the massacre. The theatrical and carnivalesque performance of the massacre was based on the homonymous theatre play by Calisto dos Lagos, who is also quoted as the film's screenwriter and dramatic director. Mueda overrides all efforts at generic classification, thus opening the category of cinematographic œuvre, as a cultural form, to new dimensions that include cinema, theatre, collective memory's modes of expression and dynamic performative cultural forms such as the mapiko, a traditional masked dance of the Makonde, which constitutes an example of a dynamic cultural practice reflecting historical processes.37 At the same time, the film's diegetic structure reveals a complex intertextual conception of the historical narration - and of the film object as a form of historical representation - questioning the operative categories of documentary and fiction's validity, giving new meanings to the film practices of re-enactment. According to Guerra, the film, as a process, is a 'documentary directly written with the image', conceived in the frame of 'a cinema of experimentation'.38 I will come back to the historical and ideological factors underlying the film's generic classification. For now, it is necessary to note that Mueda addresses the Mueda Massacre, which happened in 1960, four years before the beginning of Liberation Struggle. Its representation is based on the shooting of a popular, spontaneous and collective dramatisation of the event that, from June 1976 and for about two decades, took place every year at Mueda's public square, in front and inside of the ancient colonial administration building - that is, in the same place where the massacre happened in 1960.

The filmic organisation of the temporalities and narratives in conflict inscribes this aesthetic and political manifesto - or, better, makes a statement on the inseparability between aesthetics and politics - in the context of the new country under construction. At the same time, since the massacre's representation is based on its collective, direct and popular memory, the film - and its polyphonic enunciative system - shows the reinvention of the expressive possibilities, which would also be entwined with the new dimension of Mozambican identity's creation.

In this way, Mueda tackles the massacre's affective collective memory rather than the historical event itself. According to Guerra, it is a movie about the massacre's 'mythical significance', the transformation 'of such a cruel act into an act of joy',39 and about the self-representational forms of the people engaged in the revolutionary process. It reconstitutes the massacre's popular re-enactment, creating its definitive forms of visibility and laying, in the process, the foundations for Mozambican cinema. However, this re-constitution also contains a gesture of spatial and temporal transference, that is, the mythic nature of the past's transference into the country under present construction, a living time that is already a past tense, thus a gesture of the investment of the past's symbolic weight into the new images. The past's re-figuration comes out precisely through the present's intensity. The film comes from a history already in progression; consequently, the present - the cathartic and carnivalesque celebration of the massacre - is treated as the inaugural force of history to come. The work developed by Guerra in Mozambique may all be inscribed in this lineage, particularly the monumental fresco Os Comprometidos: Actas de um Processo de Descolonização (The Compromised: Minute of a Decolonization Process, 1984) that assembles the declarations of ex-collaborators of the colonial regime in a popular court, and which constitutes, according to the director, 'the catharsis of colonialism'.40

In Mueda, the borderline between the interior and the exterior scenes signals the genre's conflict and determines the relation between a collective body and the camera's position. The sequence-shots of the self-determined theatrical play, shot at Mueda's public square, contrast with the sequences shot inside the colonial administration's ancient building and re-staged for the film. During the shooting of these interior scenes, Mueda's inhabitants, who stayed outside the building, spontaneously performed the theatrical play again, becoming spectators of the political action staged inside the building and active participants at once. Guerra's camera shows us incessantly their double condition, which also signals the contiguity and friction between documentary and fiction.

Nevertheless, Mueda is a film without direct mise en scène since the filmed events are independent of the shooting. The work of fiction is built upon the different narrative levels' organisation in the editing process. Even if the film follows the theatre play's original structure, the editing articulates images from different (at least two) popular re-enactments of the massacre and several interviews. The narrative structure emerging from editing, the deferred temporalities and heterogeneous expressive systems' articulation create, in this way, a new memory of the massacre. At the same time, in its content and form the film is also a document about the revolutionary process in Mozambique. 'Genre's frustration'41 is the expression that Guerra uses to describe Mueda as it is a film that politically refuses both the epic re-enactment and the documentary's reality effect. It is entirely a Mozambican production, which determined the usage of black and white negative film; a film that, in spite of its generic classification as a fiction, paradoxically shows itself as a representation of reality, from which its political strength unquestionably comes. The film's archaeology reveals political frustration as well, since it would be re-edited without Guerra's participation, suffering at least two important cuts, apparently due to divergences deriving from a historical point of view that the film would adopt, and that was not officially recognised. The film's performative time did not adjust to the Mozambican political project's pedagogical time as it would not entirely sublimate the interaction between the historical and structural determinant (the Mozambican people's heroic fight for liberation) and the superstructural component (the awareness of the fight's heroism and justness and its representation).

Mueda, a film from 1979, lies on the border of a period of transformation in Mozambican cinema and the country's political project itself. To excavate the material time and space of its images brings out discontinuities, fundamental contradictions and incompatible postulates. Starting as the country's first fiction feature film, interconnecting African, Latin-American and European cinema, it became a film out-of-circulation, rarely seen, rarely shown, confined to the institutional archives, discarded as FRELIMO's political project. The film's images are deferred archives because they do not claim to be (nor are they) images from the past as they constitute, on the contrary, a disruptive force that connects transversely to the past of the 1960s and to the enunciative present of 1979, as well as finally to today and the failure of Mozambican revolutionary process. These three moments of the image punctuate the passage of time over history's discourse, ideology, and the work of memory.

O Vento Sopra do Norte, O Tempo dos Leopardos

If Guerra's film was produced in a period of transformation in Mozambican cinema as well as of the country's political project, these deep alterations might be evaluated through an analysis of the fiction features produced by INC in 1985 and 1987, O Vento Sopra do Norte and O Tempo dos Leopardos. Cinema would not only represent Mozambique's political and cultural process; it would also reveal and be an indicator of political change and ideological shifts.

O Vento and O Tempo represent a passage to fiction, as past facts could no longer be translated into historical reality through experimentation. Muedas censorship and the re-shooting of two sequences by Licínio de Azevedo clearly signal the transition to a more authoritarian and centralised period of governance in Mozambique, to which South Africa's and its allies' destabilisation policy strongly contributed. Guerra, Rouch and Godard were then gone, as were many of INC's foreign collaborators. The new war created the urgent need to legitimate FRELIMO's political project and affirm Mozambique as a coherent and undivided country at the national and international level. Epic film narratives that would represent the Liberation Struggle as a current event were, therefore, required. Event and representation would converge with a dual meaning, which is to say the Liberation Struggle's cinematic representation would not only demonstrate and reinforce FRELIMO's historical legitimacy as the only political movement that fought Portuguese colonialism, but the realistic representation would operate as a symbolic substitution of conflicts. If the Liberation Struggle is indeed represented, elements of anachronism promote a symbolic substitution. For instance, in O Tempo Januário's (Sumo Mazaze) character, the traitor, is represented as being even worse than the Portuguese as he neither has a moral reference nor is he fighting for a cause in an analogy that the public should make with Renamo's guerrilla fighters. An expanded space of historical experience was then opened through elements that intended to transform the spectator's perception. A political economy of cinema appears to guide the film's conception. Cinema was inscribed in a teleological model where there was no space for cinematic experimentation. In addition, the junction and concatenation of synchronic and diachronic orders contributed to determine and modify historical understanding. However, how is aesthetic experience enacted in these films?

It would be unfair and inattentive not to recognise the merging of poetics and politics in O Vento. José Cardoso, recently deceased, was one of the founders of Beira's cine-club in 1953 and one of the most interesting Mozambican cineastes, having started his career as an amateur filmmaker. O Vento addresses the agony of the Portuguese colonial empire through the difficulties of the daily lives of two friends, João (Gilberto Mendes) and Renato (Emídio Oliveira), in Lourenço Marques in 1968. It synthesises historical memories of the last decade under Portuguese occupation. The strength of the retrospective glimpse of this historical period repeatedly stresses ideological issues such as the multiculturalism and multiracialism of FRELIMO's project, assuring at the same time a discursive and archaeological approach to the political constructs of the time. The diegetic architecture of O Vento points to a 'futures past',42 anticipating independence, while this conception of temporality is itself the outcome of the film's diegetic structure as it narrates the time interval before João and Renato join the armed struggle. These peculiar structural outlines are particularly significant in the film's final part, when there is a time lag between the events João narrates and their visual representation. Indeed, the visual representation slightly precedes the narration. This analeptic and deferred temporality evoke the film that lies at the foundation of anti-colonial Lusophone fiction film, Sarah Maldoror's Sambizanga.43

O Vento lucidly exposes colonialism's contradictions by means of this story of engagement and voluntary enlistment. At the same time, it interrogates the propa-gandistic role of mass media contrasted with the significant organising role played by alternative media. The country's independence, represented as an event to come, raises the prospect of unending peace, and this vision transforms into a future. In the beach sequence, whose blissful delicacy recalls a similar scene in Jean Rouch's Moi, un Noir,44 Renato describes a multicultural egalitarian society that would emerge in the foreseeable future. The sequence, representing a mild interaction between Blacks and Whites, points in that same direction, as do the camera movements, a recurrent procedure and forward movement that seems to forecast the approaching future. At the same time, the sublime editing sequence in which Zita's (Lucrécia Paco) father recalls his experience as a political prisoner at Villa Algarve, the headquarters of the PIDE45 in Lourenco Marques, constitutes a mnemonic subjective re-enactment that shows the possibility of representing and repeating the empirical experience of history.

Zdravko Velimirovic's O Tempo dos Leopardos is, on the contrary, an epic film, the only film of the corpus directly representing the Liberation Struggle in its quotidian and military operations. A fiction feature co-produced with Yugoslavia, this socialist realist film treats the Liberation Struggle in the form of a didactic coloured model. If Guerra states that 'we cannot make political films on the basis of political strategies or practices',46 in O Tempo there is an evident hiatus between the film's political content, its conventional form and its teleology. It poorly serves a cause - the mythification of the liberation struggle - not hesitating to have as protagonists Pedro, The Leopard (Santos Mulungo) and Ana (Ana Magaia), whose physical and moral characteristics are evidently inspired by Samora and Josina Machel. What is at stake here is not merely the Liberation Struggle, but rather primarily - and mostly - the so-called 'civil war', therefore, not a past tense, but a lived present and expectations of the future. Consequently, at a discursive level, there is no question of returning to the past; instead it turns towards the future, the radiant future of the represented liberated areas, which might extend to the entire territory, which becomes even more important in view of the temporal dislocation performed by the film's narration. Nevertheless, what is effectively prefigured are the historical events to come, the death of Machel, anticipated by Pedro's crucifixion, and the failure of Mozambique's political and cultural project.

Guerra states that 'aesthetics is always politics' and that 'we cannot separate politics from aesthetics'.47 The political implications contained within the aesthetics of Velimirovic's film seem to assert that FRELIMO's cultural project had by then attained their fixed rigid aesthetic forms. At least that is the impression that the film leaves regarding the horizon of expectation.48

The exotic representation of the landscape and cultural forms of expression do not differ essentially from the way colonial cinema depicted the colony. At the same time, on the ideological plane, it is important to note the insistence on national unity and the notion of mogambicanidade ('Mozambicanity'), which would result from a synthesis between tradition and modernity. The indirect punishment of traditional power structures that refused to support the Liberation cause is in this regard highly symptomatic. What is remarkable in the film is the way it represents the transformation of cultural forms of expression by the Liberation Struggle, for instance in the sequence showing the FRELIMO guerrilla fighters dancing while holding rifles. On the other hand, if in the three films analysed here there is a common reluctance to use archive images from the conflict, O Tempo shows archive footage from Liberation Struggle through a second-degree narration, from which it would appear demonstrable that the documentary images and the film shots belong to the same historical and ontological category. This is even more relevant since it occurs in a film teleolog-ically-oriented by consent, but which deliberately problematises the mechanisms of propaganda, as well as the process of heroisation it enacts.

Conclusion

In the three films, spatial displacement is an important narrative procedure. It was in the north of the country that 'the bullets' begun 'to flower', to quote a line from Jorge Rebelo's poem49 and the title of Lennart Malmer and Ingela Romare film, I vãrt Land Bõrjar kulorna blomma.50 The liberation process involved spatial progression, the conquest of a territory that coincided with the geographical borders of the colonial state. This question might point to the Marxist conception of modernisation introduced by colonialism as a necessary stage leading to social revolution,51 as can be seen in the dialogue between Pedro and Armando in O Tempo. At the same time, the geographical dislocations symbolically or effectively drawn in the three films -from North to South in Mueda and O Tempo; from South to North and back to South in O Vento Sopra do Norte, the wind blowing from the North, from the Rovuma to Maputo - might indicate as well that the liberated areas' past utopian experience could reach the present and all the territory. At an ideological level, the process of spatial displacement facilitates a geographical and historical substitution: O Tempo and O Vento suggest that the new life forms experienced during Liberation Struggle, namely in the liberated areas, might be expanded to the whole country, while Mueda, showing and standing as an example of the relationship between the aesthetic subject and its object's redefinition, therefore of a new politics of representation, argued for the reorganisation and the universalisation of the aesthetic experience in the Marxist State.

There is another dislocation produced by the visual articulation of the relationship between history and memory, in the way memory becomes history. O Tempo, as indicated in the opening titles, departs from Licínio de Azevedo's idea based on testimonies about Mozambican Liberation Struggle. Jacques Ranciere's concept of 'fiction de mémoire'52 not only visually puts together the relation between affective memory and history, but also relates closely to the notions and practices of re-enactment and re-effectuation, a term with a deeper pragmatic dimension, present in the three films. In particular, Mueda has the massacre's dramatic re-enactment and the process of memory's fictionalisation at its point of departure. There is a complex articulation between history, the enunciative present, memory and their mise en rapport, which destabilises the operative categories of documentary and fiction, pointing to a politics of representation that would be inseparable from the emerging models of sensible experience53 as well as from a cinematic thinking of history.

As pointed out at the beginning of this article, the history of fiction film in Mozambique is an inseparable part of the history of the country's revolutionary project. Mueda, O Tempo and O Vento consent to inquire into the archaeology of Mozambican film forms, revealing a historical horizon of expectations. In the 1980s, Mozambique is a country quite different from the one anticipated in the first films produced by INC and even in Mueda. The Liberation Struggle liberated a new future that had not emerged in the tensional present. There was evidently a gap between past, present and future, as reflected in the complex diegetic temporalities of fiction film. Mozambican cinema had to go back to the past, towards a mythification of Liberation Struggle, avoiding the present, sensed as catastrophic. Moving images stand as symptoms of the historical conditions. It is more precisely as fiction that they constitute a diagnosis of historical reality's elements, manifesting what was unutterable in other discursive formations.

In the same fashion that Liberation cinema produced a future time, Mozambican national cinema opened up a new past, rendered as well as a main object of literature and artistic production. The way post-independent Mozambique represented the Liberation Struggle is fundamental to how we approach the ideological issues at stake in that period as it makes concrete historical motion visible. And today, with the re-emergence of fiction film, it is important to look at how this historical process, specially the period of transition from the 1980s to the 1990s, is cinematographi-cally represented in a new interpretative framework and converted into a new audiovisual memory. Given this, current ideological modes of seeing the past then become visible.

In memoriam José Cardoso

(1930-2013)

1 In this article we are referring to the version of the film edited for DVD by Arcadia Filmproduktion (O Mundo em Imagens -Filmes do Arquivo do INAC / Views from the World - Images from the Archive of INAC, 2012, see footnote 9), the result of the digitisation and the digital film-restoration of the print negative preserved in Mozambique's National Institute of Audiovisual and Cinema's (INAC) collection.

2 N. de Sousa, 'If you want to know me' (Se me quiseres conhecer) in G. Moore, ed., The Penguin Book of Modern African Poetry (London: Penguin, 2007), 217.

3 F. Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (London: Penguin, 2001).

4 The Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, founded in Dar es Salaam in 1962 to fight for Mozambique's independence. Eduardo Mondlane, murdered in 1969, was FRELIMO's first president.

5 F. Arenas, Lusophone Africa - Beyond Independence (Minneapolis/Londres, University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 103-157.

6 P. Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde (Minneapolis: Minneapolis University Press, 2002).

7 K. Marx. Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts of1844 (New York: International Publishers, 1993).

8 V. N. Volosinov, Marxism and the Philosophy of Language (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1986).

9 See footnote 1. See also http://www.arcadia-film.de/en/index.php/projects/multimedia_installation/o_mundo_em_imagens _dvd_edition_mit_filmen_aus_mosambik, last visit 25 October 2013. The double DVD also contains José Cardoso's documentary Canta meu Irmão (Sing my brother - and help me to sing, 1982) and a selection of Kuxa Kanema newsreels. Further information about Kuxa Kanema in this article.

10 Portuguese Cinematheque's excellent work in the field of conservation and restoration of audiovisual heritage is compromised by the present government's cultural policy (or rather by the absence of cultural policy).

11 The decree-law 57/76 of March 4 created the INC, a public institution answerable to the Ministry of Information, which is highly significant from a political and juridical point of view. The National Cinema Service (SNC), established in November 1975, just five months after independence, precedes INC's foundation. In this regard, see G. Convents, Os Moçambicanos perante o Cinema e o Audiovisual: Uma História Político-Cultural do Moçambique Colonial até à República de Moçambique (1896-2010) (Maputo: Edições Dockanema and Afrika Film Festival, 2011), 436-446. See also Atneia, Database of legislation published in the Boletim da República de Moçambique, Mozambique's official gazette, since 25 June 1975, http://www.atneia.com/, last visit 23 October 2013.

12 According to Pedro Pimenta in G. Convents, Os Moçambicanos perante o Cinema, 563.

13 Ruy Guerra, interview with Raquel Schefer, Paris, 26 February 2013.

14 'As society and the state's leading force, the FRELIMO party must guide, mobilise and organise the masses in the task of building the People's Democracy, carrying out the state apparatus' construction in a manner that could materialise the strength of the worker-peasant alliance and serve as an instrument for the construction of socialist society's ideological, economic and cultural basis', 'Preparatory text for 1977 FRELIMO's III Congress in L. Moita', Os Congressos da FRELIMO, do PAIGC e do MPLA (Lisboa: Cidac and Ulmeiro, 1979), 22.

15 R. Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

16 J. L. Cabaço, Moçambique, Identidades, Colonialismo e Libertação (Maputo: Marimbique, 2010), 271-277.

17 A. Cabral, 'National Liberation and Culture', History is a Weapon, http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/cabralnlac.html, last visit 23 October 2013. See also A. Cabral, 'Libertação Nacional e Cultura' in M. Ribeiro Sanches, ed., Malhas que os Impérios Tecem: Textos Anticoloniais, Contextos Pós-Coloniais (Lisbon: Edições 70, 2011), 355-375.

18 M. Diawara, African Cinema: Politics & Culture (Bloomington et Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 1992), 88-103.

19 Margaret Dickinson shot Behind the Lines in a liberated area of Niassa Province in 1971.

20 R. van Lierop, The Struggle Continues, 1971. After independence, in 1975, van Lierop directs The People Organised.

21 In 1977, FRELIMO's programme states: 'At this stage, the ideological struggle is emphasised in order to edify the New Man, the socialist Man (sic), the free Man (sic) from all obscurantist and superstitious subserviences, the man who masters science and culture and who assumes society's fraternal and collective duties and relationships'. L. Moita, Os Congressos da FRELIMO, do PAIGC e do MPLA (Lisboa: Cidac and Ulmeiro, 1979), 22.

22 See J. L. Godard, 'Nord contre Sud ou Naissance (de l'Image) d'une Nation 5 films émissions de TV', Cahiers du Cinéma, 300 (May 1979), 70-129. Godard's visual essay was published in Cahiers du Cinema's 300th issue: it is a hybrid piece, combining texts and images, excerpts of Godard's travel journal in Mozambique, using photomontage procedures: 'En route to the village where the comrades with the Super 8 stock are going to project their film. Stop on the banks of the Limpopo River. Children. A Polaroid colour instamatic. The first image. Of men. And of women' (119).

23 F. Cigarini, Ten Days with the Guerrillas of Free Mozambique, 1972.

24 J. C. Martinez Corrêa and C. Luccas, 25 - Vinte e cinco, 1975.

25 Margarida Cardoso directed an excellent documentary about Kuxa Kanema newcast: see M. Cardoso, Kuxa Kanema: O Nascimento do Cinema, 2003.

26 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Catarina Simão and Raquel Schefer, Maputo, 16 September 2011.

27 J. L. Godard, To Alter the Image, 1982.

28 J. L. Godard, Changer d'image: Lettre à la bien-aimée, 1982.

29 'Retalhos de um Moçambique. M. Dési, 'Retalhos' in As Armas Estão Acesas nas Nossas Mãos: Antologia Breve da Poesia Revolucionária de Moçambique, collective edition (Porto: Edições 'Apesar de Tudo', 1976), 50.

30 A. Badiou, Cinéma (Paris: Nova Éditions, 2010), 229.

31 L. Daston and P. Galison, Objectivity (Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2007).

32 M. Foucault, Larchéologie du savoir (Paris, Gallimard, 2010).

33 R. Guerra, The Unscrupulous Ones, 1962. The designation 'Cinema Novo' was employed for the first time in Brazil in the poster of Os Cafajestes.

34 R. Guerra, The Guns, 1964.

35 See M. Newitt, A History of Mozambique (Bloomington and Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1995); J. L. Cabaço, Moçambique, Identidades, Colonialismo e Libertação (Maputo: Marimbique, 2010), 262-271; Cahen, 'Os heróis de Mueda' in Agora: Economia, Política e Sociedad, 2 (August 2000), 30-31; D. Cabrita Mateus, 'Conflitos sociais na base da eclosão das guerras coloniais' in A. Simões do Paço, R. Varela, S. Van der Velden, eds., Strikes and Social Conflicts: Towards a Global History (Lisboa : International Association Strikes and Social Conflict, Instituto de História Contemporânea da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2012), 87-93; '16 de Junho. Mauvilo. Sobreviventes e Massacres', unsigned article in Tempo, 350 (1977) 42-49; Relatório administrativo de 17 de Junho de 1960 (Administrative Report from 17 June 1960).

36 'The guerrilla called "liberated areas" to the territorial surfaces where the administration was already made under its control. (...) The concept... was, for the FRELIMO's committee, even deeper since it integrated the idea that the fight for the socioeconomic transformation of people's life was also taking place in those areas. J. L. Cabaço, Moçambique, Identidades, Colonialismo e Libertação (Maputo: Marimbique 2010), 274.

37 See P. Israel, 'Lingundumbwe: Feminist Masquerades and Women's Liberation, Nangade, Mueda, Muidumbe, 1950-2005', in this issue. See also P. Israel, 'Formulaic Revolution Song and the "Popular Memory" of the Mozambican Liberation Struggle', Cahiers d'Études Africaines, 197 (2010), 181-216.

38 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Raquel Schefer, Paris, 26 February 2013.

39 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Catarina Simão and Raquel Schefer, Maputo, 16 September 2011.

40 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Catarina Simão and Raquel Schefer, Maputo, 16 September 2011. The documentary Treatment for Traitors (I. Bertels, 1983) was edited with original footage shot by Ruy Guerra during the trial. According to the filmmaker, the raw footage was sold to Bertels by INC (Ruy Guerra, interview to Raquel Schefer, Paris, 26 February 2013). Some of the sequences are available online. On 1982 'Meeting of the Compromised, see V. Igreja, 'Frelimo's Political Ruling through Violence and Memory in Postcolonial Mozambique', Journal of South African Studies, 4 (Dec. 2010), 781-799.

41 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Catarina Simão and Raquel Schefer, Maputo, 16 September 2011.

42 Koselleck, Futures Past.

43 S. Maldoror, Sambizanga, 1972.

44 Rouch, I, a Negro, 1958.

45 The International and State Defence Police, Estado Novos political police, introduced in Mozambique in 1956,

46 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Catarina Simão and Raquel Schefer, Maputo, 16 September 2011.

47 Ruy Guerra, Interview with Catarina Simão and Raquel Schefer, Maputo, 16 September 2011.

48 R. Koselleck, Futures Past.

49 J. Rebelo, 'Vem contar-me o teu destino irmão' in M. de Andrade, ed., Antologia Temática da Poesia Africana (Lisboa: Editora Sá da Costa, 1970), vol. 1, 77-78.

50 L. Malmer and I. Romare, In our Country Bullets Begin to Flower, 1971. In 1978, Lennart Maimer directs Vredens Poesie (Poetry of Anger), a fiction feature about Liberation Struggle, combining documentary and re-enacted sequences.

51 Karl Marx, 'The British Role in India', Marxists.org.archive, http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1853/06/25.htm, last visit 16 October 2013.

52 'Fiction of memory'. J. Rancière, 'La fiction documentaire: Marker et la fiction de mémoire' in La fable cinématographique (Paris: Seuil, 2001), 201-216.

53 J. Rancière, Malaise dans l'esthétique (Paris: Galilée, 2004).