Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.28 n.1 Cape Town 2002

Home-made ethnography: Revisiting the Xhosa in Town trilogy1

Leslie Bank

Institute of Social and Economic Research, Rhodes University

Introduction

Duncan Village in East London is a well-worked site of knowledge production in anthropology. In the 1930s, Monica Hunter conducted fieldwork there as part of her classic study Reaction to Conquest (1936). Written up as part of an exploration of the cultural impact of urbanisation on the Pondo (in a broad sense a subset of Xhosa-speakers), she left it to the end of her monograph, offering a "culture contact" perspective. Twenty years later, Philip and Iona Mayer and their colleagues from Rhodes University embarked on extended field-work in the old East Bank location (subsequently called Duncan Village). Their engagement with people of the East Bank proved to be much longer and more significant than Hunter's, and resulted in three anthropological monographs: Reader's The black man's portion (1960), Philip Mayer's Townsmen or tribesmen (1961) and Pauw's The second generation (1963). Collectively, these studies became known as the Xhosa in Town trilogy. They divided the population of East London into two distinct socio-cultural categories: the so-called School people or abantu basesikolweni, who were seen to be receptive to European cultural influences, urbanisation and Christianity, and the Reds, the abantu ababomvu or amaqaba, who were said to reject western values, lifestyles and Christianity. The latter, who celebrated their rural traditions and values in the city, fascinated the Mayers. They admired the refusal of the Reds to relinquish their unique cultural identities in the face of contact with European culture.

In the anthropological literature on urbanisation and social change in southern Africa the trilogy thus stood out for its ethnographic account of cultural conservatism and the persistence of tradition in a changing urban context. Townsmen or tribesmen in particular, was viewed as a classic anthropological study which demonstrated the capacity of poor rural migrants to resist cultural domination and defend their traditions in an industrialising South African city. In a context where anthropology as a discipline was starting to grapple with the impact on communities of rapid social and cultural change, the Mayers' work provided a good example of the lengths to which some people would go to resist acculturation and insulate themselves from western culture. But the initially positive reception given to the trilogy faded during the 1970s as the politics of social anthropology as a discipline came under increasing scrutiny.2 In this new intellectual climate, the Mayers' celebration of Red identities in East Bank became problematic, especially since they seemed to be suggesting that some Africans in the Eastern Cape were incapable, or at least unprepared, to modernise and preferred to develop along tribal or ethnic lines. They came to be accused, especially by scholars working outside of anthropology, of being apologists for apartheid.3

From within anthropology, the assessment of the trilogy also changed. With the increasing influence of Marxism, the Mayers and their colleagues were criticised for theoretical conservatism, lack of historical perspective, and failure to situate adequately their analysis of cultural change within the political economy of colonialism and racial capitalism. The trilogy was seen to have overemphasised the salience of the Red-School, townsmen-tribesmen divide. It was pointed out that other divisions, such as those based on class difference, were ignored and that these studies also under-estimated the situational dynamics of identity formation. The essential critique of the Xhosa in Town project was that it had been theoretically over-determined and became locked into an outmoded "two-systems cultural model", which did not account for the enormous complexities of urban African identity formation in the 1950s. The critics had made some powerful points and, in 1980, Philip Mayer recast his analysis of Red and School in more politically fashionable terms. Drawing on the work of the French structuralist Marxist, Louis Althusser, he argued that Red and School were, in fact, both long-standing rural resistance ideologies, which had their roots in the history of African dispossession, missionary activity and colonial exploitation in the nineteenth century Eastern Cape. Significantly, while Mayer added historical depth and context to his earlier work, he did not suggest that he had originally overestimated the salience of the Red-School divide. He pointed out that the material and social basis for this division was historically rooted, but had been progressively undermined with apartheid-driven agrarian change, first with the introduction of betterment planning in the 1950s and then bantustan development which increased rural poverty and landlessness in the 1960s and 1970s.

In this paper I revisit the Xhosa in Town project in the light of extensive interviews with East and West Bank residents who lived in the old locations described by the Mayers and their colleagues in the 1950s. Over the past few years I have been researching the claims lodged before the Eastern Cape Restitution Commission by former East and West Bank residents who were forcibly moved under apartheid laws away from the East London city centre to outlying black residential areas from the mid-1960s onwards. The most significant of these was Mdantsane, a satellite, commuter-township established on farmland 25 kilometres outside the city as part of the new Ciskei homeland.

In establishing what claimants had lost as a result of the removals, it was necessary to reconstruct a social history of the old locations prior to forced removals. It was in the process of undertaking this research, which I conducted jointly with Landiswa Maqasho,4 that I started to question the ways in which the Xhosa in Town project had represented African urban life. In the restitution work, our sample population was mainly comprised of townspeople. Most of the rural migrants on whom the Mayers had focused were either no longer living in the city, having returned to their home villages, or were not aware that they were entitled to apply for restitution. This meant that the core claimant groups were made up of "borners", African and Coloured families who had grown up in the locations. It has been their recollections, memories and life histories that have allowed me to look at the Xhosa in Town project with new eyes and develop an alternative perspective on the social and cultural dynamics of location life in East London during the 1950s.

Like many others who have commented on this project, I am concerned to understand why the Mayers and their colleagues emphasised particular responses and not others. Why did they stress the role and importance of tradition in the city rather than local engagements with cosmopolitan styles and identities? How could urban researchers, who explicitly stated that their aim was mainly "to describe and record", end up presenting such a single-stranded view of urban life and identity formation?

In trying to address these questions I veer away from the usual accusations of political and theoretical conservatism and focus instead on their field-work practice. I suggest that the arguments that came to define the Xhosa in Town project were profoundly shaped by fieldwork strategies. More specifically, I argue that the emphasis on migrant conservatism was a direct consequence of the fact that so much of the fieldwork for this project was conducted in the old wood-and-iron houses and their backyards, where migrants lived and socialised. A different, more varied fieldwork strategy, one which shifted attention away from the domestic arena to more public sites of social interaction and cultural production - like streets or dance halls - would, I believe, have generated a very different understanding of the location's cultural dynamics. My own critique of the Xhosa in Town project is therefore that it produced of a series of "homemade" ethnographies that were ultimately unable to capture the richness, variety and complexity of African urban culture in East London.

The Xhosa in Town project

As an intellectual project, the Xhosa in Town series emerged in the wake of burgeoning scholarships on urbanisation and social change on the Zambian Copperbelt from the Rhodes Livingstone Institute (RLI), established by the British government in Northern Rhodesia in 1937. Godfrey Wilson's path-breaking study of the mining community at Northern Rhodesia's Broken Hill laid the foundation for a new tradition of urbanisation studies, which became the RLI's hallmark.5 Within the colonial milieu there was much discussion around the concept of "stabilisation" - a term used to refer to the length of stay of Africans in the city and the increasingly permanent urban settlement of African workers and their families. According to Ferguson, RLI anthropologists aimed to challenge the prevailing wisdom in colonial government circles that a "tribesman" in town remained a "tribesman".6 They intended to counter the assumptions of colonial administrators and mine owners that African townsmen constituted "a very primitive population".7

It was in this political context that liberal anthropologists at the RLI argued that the colonial regime had underestimated the capacity and speed with which Africans entering urban areas were able to adopt and absorb essential aspects of modernity, and western values and life-styles. They argued that Africans responded to urbanisation and social change by shedding their rural "tribesmen" identities and adopting new urban identities, as captured in Gluckman's phrase, "the African townsman is a townsman."8 Their observations formed the basis of what became known as "situational analysis", which emphasised the ability of individuals to shed older identities and adopt new ones as the situation demanded. However, as Ferguson has argued, this emphasis on the capacity of urban workers to redefine themselves situationally was embedded in a wider narrative of modernisation and progress, in terms of which urban Africans were inevitably en route to civilisation and modernity.9

These ideological assumptions also shaped the Xhosa in Town project. Philip Mayer and his colleagues were interested in showing "how some Xhosa during the course of their East London careers undergo the transition from migrant to real townsmen and others do not."10 They defined the process of urbanisation as, on the one hand, a slackening of ties with the former rural home to the point where the migrant no longer felt the pull of the hinterland and, on the other, a simultaneous acquisition of western values and cultural forms. The point at which a person's "within-town ties" came to predominate over their "extra-town ties" could be revealed, they suggested, by a study of their relational networks, while their changing socio-cultural orientations could be explored through an assessment of changing norms and values in town.11

Philip and Iona Mayer distinguished the quantitative process of urban "stabilisation", equated with "length of time in the city", from the qualitative process of "urbanisation", the acquisition of a westernised lifestyle, norms and values. They argued that there was no reason to assume, as some Copperbelt studies had, that staying for long periods in the city necessarily led to loss of tribal identity and cultural orientation. Philip Mayer argued that a large segment of East London's migrant labour force had become "stabilised" without being "urbanised" (that is, without adopting western values).12 He suggested that this was not simply due to apartheid's enforced migrant labour, but was also a product of a deep-seated rejection by many migrants of western culture and Christianity. In East London, amaqaba (Red) migrants in particular, showed little interest in socialising outside of a narrow group of "home mates" (abakhaya) in town. Moreover, they focused their energies on saving money to build up their homesteads (imizi) for retirement. These men, according to the Mayers, were tribesmen in town. Rather than picking up or discarding identities at will, as suggested by the Copperbelt studies, the Mayers argued that the amaqaba identity was a relatively fixed, total identity that had become internalised in town through a process of "incapsulation".13

To ensure that the Xhosa in Town project focused not only on migrants, Philip Mayer commissioned a study of urban-born, second-generation families in the East Bank location. Undertaken in the late 1950s, it constituted the third volume in the series - Pauw's The second generation. Pauw extended the Mayers' insights by gauging the level of East London-born Africans' absorption of western values and lifestyles. He worked with a series of categories or "social types" based on a combination of criteria including household material, culture, education, income and level of "westernisation". He concluded that while second-generation families were considerably more "westernised" than those of most migrants (for instance, they were less inclined to use witchcraft), their transition to "full urbanisation" was incomplete and disparate. He noted the continued adherence of many second-generation families to traditional Xhosa religious beliefs and suggested that born and bred urbanites in East Bank ranged in their cultural orientation from what he called "semi-Red" to "fully westernised".14Despite Pauw's interest in broader processes of cultural change and identity, his work focused almost exclusively on the domestic domain and the changing urban family structure. This notion of the "domestic sphere" as the primary site of cultural knowledge and social organisation, and the key locus of socialisation and cultural transmission, in fact, underpinned the Xhosa in Town project as a whole. The failure of the trilogy researchers to engage effectively with the dynamics of social life and cultural production in public spaces beyond the home, I argue later, created significant social and cultural "blind spots".

The fact that Townsmen or tribesmen became an anthropological classic in the 1960s had much to do with how its arguments were constructed and how they fitted into the dominant themes and conventions of disciplinary knowledge at the time. The Mayers' "discovery" and skilful representation of the secret and socially insulated world of conservative Red migrants cleared well-understood and respected ethnographic space. Finding "the village in the city', a bounded rural culture surviving in a rapidly industrialising urban centre, generated enormous interest in a discipline pre-occupied with issues of cultural insulation, closure and survival. Clifford explains that it was common at the time for the "cleared spaces" of scientific work in anthropology to be "constituted through the suppression of cosmopolitan experiences ,.."15 The complex, fluid and seemingly unbounded creolised dynamics of city life, he argues, was not exactly what anthropologists working in the dominant paradigm wished to encounter. It was an anthropologist's nightmare, as Mintz remarked of the Caribbean, to find

houses constructed of old Coca-Cola signs, a cuisine littered with canned corned beef and imported Spanish olives, rituals shot through with the cross and the palm leaf, languages seemingly pasted together with ungrammatical Indo-European usages, all observed within the reach of radio and television.16

But it was not the failure of the project to grasp the creolised cultural dynamics of urban life that initially attracted the attention of critics, but rather the absence of a thorough analysis of political economy, labour migration and colonial exploitation. In the 1970s, Bernard Magubane, drawing on neo-Marxism and dependency theory, attacked the Xhosa in Town project for failure to grasp the complexities of colonial and racial capitalism. Magubane, however, also rejected the linear models of cultural development that seemed to underpin these studies, which presented European civilisation and westernisation as the desired end-point of African cultural development. He argued that urban Africans generally did not seek to mimic western ways, but were constantly adapting, re-interpreting and reworking western cultural influences through the prism of their own local cultural experiences. In subsequent critical reviews of the trilogy, such as those by Moore and Mafeje, it has been suggested that the contrast between Red and School was overdrawn and that, in reality, the urban and the rural co-existed and were more intertwined and overlaid. The problem with the cultural analysis of the trilogy, it was suggested, was that it seemed to miss the large social and cultural spaces that existed "in-between" tradition and modernity. Yet in revisiting East London's old locations through the narratives of their former residents, it is not the complex integration of tradition and modernity that they emphasise, but the ascendancy and dominance of cosmopolitanism as a social and cultural force. A careful reading of Monica Hunter's 1936 account of life in East Bank provides a useful starting point for addressing this issue.

Revisiting East Bank

Monica Hunter's account of the cultural dynamics of the East London locations in the 1930s is in many ways strikingly different from that presented in the trilogy twenty-five years later.17 Unlike the Mayers, who were struck by the cultural conservatism of city migrants and the desire of many to defend rural cultural values and orientations, Hunter was alarmed by the speed with which newly urbanised individuals and families were changing their outlooks and orientations in the city. She was, for instance, concerned at the enthusiasm with which location residents, some of them in the city only briefly, desired money and modern things:

Money gives power to obtain so many of the desired things of European civilization - better clothing, housing, furnishing, food, education, gramophones, motor-cars, books, power to travel - all the paraphernalia of western civilization is coveted. Again and again old men spoke to me of how intense was the desire for money in the younger generation.18

She noted that, "in town it is smart to be as europeanised as possible. In their dress men and girls follow European fashions - 'Oxford bags', berets, sandal shoes. Conversation is interlarded with European slang ... Houses, furniture, and food are as European as earnings permit."19 "Raw tribesmen" found themselves increasingly marginalised:

The values in town are European, not tribal. Status depends largely on wealth and education and these entail europeanization . Knowledge of tribal law, skills in talking, renown as a warrior, and even the blood of a chief's family, count for comparatively little in town. These conditions make for the speedy transference of at least the superficialities of culture.20

Even in terms of social life and entertainment, Hunter argued, tribal influences were on the wane. She observed that tribal rituals were not held in town:

There is little Native dancing ... Young people gather in private houses, particularly on Friday and Saturday evenings, for parties, but here European fox trots (sic) were more often performed than the old Bantu dances. And the music is European or American ragtime. About the street one more often hears ragtime hummed than an old Bantu song.21

In highlighting this appetite for western-style entertainment, she noted that the location had its own cinema, "at which there are two evening performances and one matinee a week."22 She also provided a detailed inventory of a wide range of social clubs, societies and churches operating in East Bank. They included dancing clubs and musical societies specialising in European and American styles, savings groups, tea clubs and a wide variety of sports clubs. Her fluency in Xhosa and close connections with the township elite afforded access to these associations. During her three months in East London, Dr W.B.Rubusana,23 leader of one of the location's largest Christian churches and a founding member of the African National Congress, hosted her. Through Rubusana, she appears to have been allowed to walk the streets and enter households almost at will. Consequently she encountered a wide spectrum of township life and developed a perspective, which encompassed aspects of both private and public worlds. Her view was framed, however, within a model of "culture contact" and "detribalisation" that precluded her disguising concerns about the social consequences of rapid social change.

The cosmopolitan cultural influences alluded to by Hunter in Reaction to Conquest seem to have deepened significantly during the 1940s and 1950s. They emerged as the central theme in the narratives of former East Bank residents. Many identified the Second World War as a political and cultural watershed, a period during which location residents became more aware of their rights and were profoundly affected by popular transnational cultural forms. In the late 1940s, drought in the Ciskei pushed a new wave of rural youth to the city in search of work and the possibility of permanent urban residence. On the streets of East Bank they encountered local urban-born youths who exuded a new self-confidence, a fashionable look and a street-wise modern style, which was now more conspicuous than ever. On the political front this new self-confidence was reflected in the formation of a dynamic branch of the African National Congress Youth League in East London in 1949. The Youth League, led by the multi-talented triumvirate of C.J.Fazzie, A.S.Gwentshe and J.Lengisi, broke ranks with the more conservative African National Congress old guard in the locations and injected new life and energy into resistance politics.24 With key political figures like Gwentshe and others involved in popular jazz bands, theatre and dance groups and sports clubs, there was a significant overlap between struggle politics and cosmopolitan cultural orientation. This is not to suggest, as Lodge points out, that the political leadership did not try hard to bridge the divide between urban and rural youth. It is simply to note a growing infatuation amongst the East Bank youth with a fashion, music and entertainment-driven "popular modernism".25

According to former residents the cultural dynamism of the late 1940s and 1950s had diverse sources. Some attributed the changes to the influence of returning Second World War servicemen. Others associated them with the opening of new factories and the growth of a local urban working class. Yet others referred to events on the Reef and the popularity of South African magazines like Drum, Bona and Zonk, which kept location residents abreast of cultural developments in larger cities and abroad. Whatever the reasons, there was consensus that the post-war period signalled "a local cultural renaissance" that raised cosmopolitan influences in location life to new levels. It initiated an explosion of new music groups, sports clubs and dancing styles, and brought a succession of musical, sports and dance acts to the city. One former resident explained:

It felt like we had become the Sophiatown of the Eastern Cape. We had the jazz bands, the politicians, sportsmen and the style. We were up with all the new trends. Here in the location we did not have much time for tradition and tribal culture. The guys had come back from the war with a new confidence and there was a great expectation of change.26

In writing the history of Drum magazine, Michael Chapman points out that when the magazine had started in the early 1950s, it carried stories about tribal customs and dance, which attracted such negative readership response, that they had to be dropped. One reader reported:

"Ag, why do you dish out this stuff, man?" said the man with the golliwog (sic) hair in a floppy American suit, at the Bantu Men's Centre [in Johannesburg]. "Tribal Music! Tribal history! Chiefs! We don't care about chiefs! Give us jazz and film stars, man! We want Duke, Satchmo, and hot dames! Yes brother, anything American. You can cut out this junk about kraals and folk-tales . - forget it! You are just trying to keep us backward, that's what! Tell us what is happening here, on the Reef!"27

Such a view was common in East Bank too. Young people in particular, did not want to hear stories about tribal culture so much as to keep up with metropolitan styles, watch American movies and engage in dynamic new urban cultural forms and styles-in-the-making. Informants recounted stories about the notorious shebeens on Ndende and Camp Streets, tsotsi gangs, including some called the Vikings and the Italians, jazz events at the Peacock Hall and political meetings on Bantu Square. They also remembered Coca-Cola fashion shows and ballroom dancing at the Social Centre, B-grade American movies at the local Springbok bioscope, and exciting sports and social events hosted at Rubusana Park.

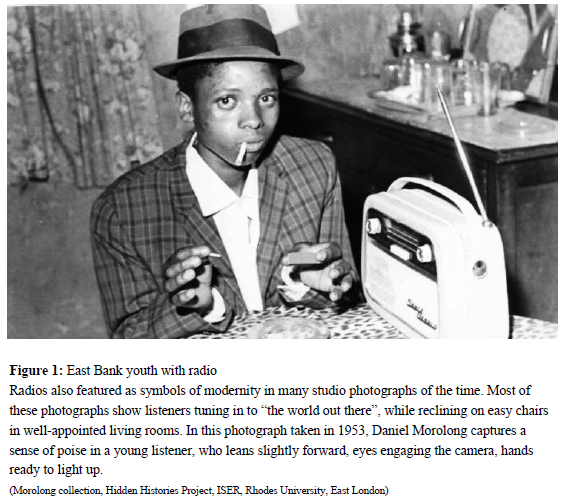

As in Sophiatown and Soweto,28 East London's urban youth fed on images of black America. Starting in local tearooms and on the household verandas, where people would listen to the radio and read magazines, and at the cinema where American movies played all week, location residents experimented with new fashions. On the streets youths copied imported styles, adapted them and put them on public display, whilst at the dance-halls on Saturday night many were dressed to the nines. Mrs Mthimba recalls:

Dressing up became a big thing. There was always talk about what was new in the shops on Oxford Street [East London's main shopping precinct]. Many of us bought outfits from "La Continental", a fashion shop, which had good Italian gear in the North End. Some of the older men would not buy off the shelf. They preferred to have their suits made up by a tailor, of which there were many in the location and the North End.29

For men, Panama hats and light Palm Beach suits became very popular after the war. But soon darker Christies "rollaway" 16-gallon hats, the doubled-breasted suits, neckties and Italian shoes came in. Ladies wore brown golf shoes, stockings, shiny knee-length dresses and white blouses, often with a colourful cardigan. Mrs Macanda remembers:

For the ladies, Saturday was always a busy day. Sometimes we would change three times. First, to do some housework, then to go out to the sports fields to watch rugby or soccer, and then into our evening dresses for the Peacock Hall. Even on Sundays, we would dress up for church and then get ready for social get-togethers in the afternoon.30

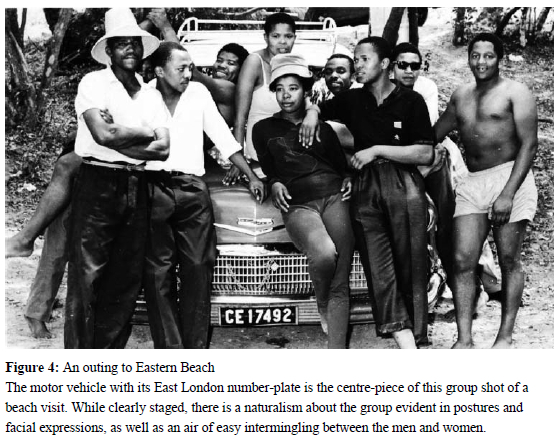

There was a competitiveness about dressing and style. Everyone wanted to look good, especially in American styles. The ultimate symbol of success was the automobile, especially a big American car, which was frequently used as a photographic prop in the 1950s.

The unkempt street ruffians described by Hunter in the 1930s, had evolved into tsotsis by the 1950s and also began to embrace the quest for style.31They no longer wore just a checked cap, a rough blazer and broad trousers. As on the Reef, their trademark was narrow-bottomed trousers called "zoot-suits". They, too, experimented with new outfits. Ronnie Meinie describes how two famous tsotsi gangs honed their styles:

The Vikings suddenly became very style conscious. They would wear Oxford bags ("toffs") and two-tone shoes. They also took to wearing caps with the peaks cut off and baggy (European) Italian-style jackets, gathered up at the waist. The Italians (another gang), on the other hand, wore tight-fitting stovepipes, Embassy jackets and Crockett and Jones shoes. The other brands of shoes they liked were Saxons and Freemans. They also wore button-down shirts and were sometimes seen with carnations in the lapels of their jackets.

The most distinctive feature of the Italians, however, was the way they modified their shoes. In order to make them look long, sleek and sharp, they used to cut off the heels so that the toes would point up in the air.

On Saturday nights the gangs would gather at the dance-hall and social events. They were no longer ruffians. They were dressed to kill. I remember watching in trepidation as they gathered on opposite sides of the halls. When both gangs gathered in numbers, there was sure to be trouble. It often started as an argument about a lady.33

In the midst of the infatuation with American styles and the increasingly predatory tsotsi street cultures, a few local individuals stood out in the narratives gathered. Most famous was the flamboyant Peter Ray Nassua, a trade unionist who claimed to be related to the great ICU leader, Clements Kadalie, and to be an American, although locals said he came from Johannesburg. He was a trickster who lived by his wits. In East Bank he was known for his stylish dress rather than his union work and came to epitomise the prevailing American style. He wore Al Capone black-and-white suits with two-tone shoes and a necktie. He drove a black Daimler with his name inscribed on the side. He had his own chauffeur who wore a white suit. To complete the image, he employed a bodyguard, a man called Ngonyama ("lion"), who looked out for him and fought his street battles. Reverend Hopa recalls:

I remember this guy [Ngonyama] in town. He would always come strutting along with his whippet dog on a lead. He liked to cross Oxford Street at the OK Bazaars and walk over to the Netherlands Bank, swaggering in his iron-tipped shoes and his Texan tie. Ordinary people were so impressed with him that they would sometimes clap as he crossed the road. He loved that!34

Mbhuti Adonisi added:

Peter Ray liked to drive his car around the location, leaning out of the window and greeting people as he went. He would often suddenly stop the car and get the children to push it to the ICU hall. When they reached the hall, he would reach into his pocket and toss a few coins for them.

He was a real showman who was always involved in some money-making scheme. I remember in 1952, Peter Ray was featured in Drum magazine. He was on a crusade to sue the state of Israel for the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. There seemed to be no money-making venture that slipped Ray's eye.35

Other more sinister characters were also on the streets. One was Bortjies from Ndende Street. It was said that Bortjies' father had died when he was young and that his mother had brought him up. Always stylishly dressed in an Italian suit, he worked as a dancer at night at East Bank's "Moon Nightclub" and performed as a part-time musician. Bortjies, it was reported, thought of himself as the king of Ndende Street - a tough guy regularly involved in street brawls whom everyone feared.36

This deepening of cosmopolitan influences is unsurprising given the far-reaching economic changes in the city. Following the introduction of secondary industry in the 1940s East London's economy grew rapidly. New industries brought new jobs and more money for consumption. The growth of the city's SA Railways depot increased travel possibilities and opened new avenues for cultural flows into and out of the city. The new transport network enabled a stream of musical bands and shows to visit the location. Local sports teams were also able to participate in regional and national tournaments. Department stores on Oxford Street brought in new consumables, cosmetics, newspapers and magazines.

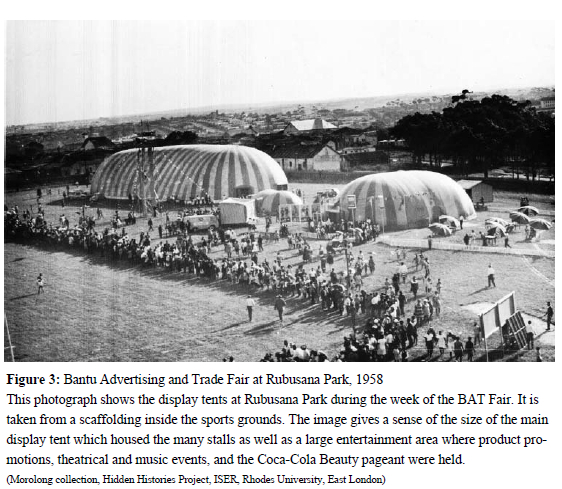

For some East Bankers, the one memorable consumer event of the 1950s was the week-long Bantu Advertising and Trade (BAT) Fair, sponsored by cosmetics conglomerate Lever Brothers. Set up at the location's Rubusana Park sports grounds, it was a lavish affair with literally hundreds of stalls displaying new products and offering demonstrations, entertainment events, beauty pageants and fashion shows. Sybil Hans, who was in her thirties at the time, relates that:

The range of products at the BAT Fair was bewildering. There were stores for various skin lighteners, Laurel perfume, Ponds skin cream and Cashmere perfume. There were a lot of salespeople and everyone had a chance to try and buy the new products. There were also demonstrations. I remember the "Mr Power-Foam" campaign for Omo. We were so impressed with the way this detergent could make clothes whiter and brighter with less rubbing and scrubbing. Many of us could not afford the expensive polishes, like Sunbeam, and would make our own cheap equivalent by mixing candle wax and paraffin to clean our floors - some of us also made do with blue soap, instead of the more expensive products like Omo and Sunlight.37

The enthusiastic engagement with the "world out there" that such images convey was combined in East Bank with a deepening culture of resistance. In 1952 political riots shook the location as urban youth and political activists pitted themselves against gun-wielding police and army troops. Ordinary people were caught up in constant cat-and-mouse struggles with police and government officials wanting tighter political control. Corruption in the police force and among officials at the location's municipal offices, known as KwaLloyd after an early location administrator, helped people navigate their way around the laws and technicalities.

The breadth of the legal regulations and the frustration of the location authorities at people's ability to subvert law enforcement, meant that no one felt safe when municipal police embarked on regular pass raids and document checks. A frequently repeated story concerned an incorruptible black municipal police sergeant called Manci, who oversaw pass arrests. Manci was greatly feared for his door-to-door raids and would reportedly brag that he could drive his victims "like cattle" to the police station. However, Manci had one major weakness: he was illiterate. People took advantage of the fact that he could not differentiate between the standard orange lodger's permit and a similar looking dry-cleaning slip. It was said that you were safe in "Manci's location" as long as you had a dry-cleaning slip in your pocket - something that has remained a standing joke among old East Bankers.

Migrants' participation in this street-wise, and at some levels playful, culture of resistance was limited. Political activists and urban-born youths said that often the migrants could not be trusted and were inclined to reveal incriminating information if arrested. Amaqaba migrants' unwillingness to participate in either the growing culture of resistance or to embrace the new cosmopolitanism sweeping through the location, increasingly marginalised them and led to them frequently being ridiculed and abused as spoilers, unprepared to come to the party.38 Reflecting on the mood of the old location in the 1950s, Pule Twaku spoke of a new feeling in the township, which made it increasingly difficult for migrants to move around freely:

We would spot them a mile off just by looking at the way they walked, at the awkward fit of their jackets, at the way they wore their trousers and at their shoes. We could see they had no style, that they were outsiders.39

Twaku explained that these country bumpkins (imixhaka) were mercilessly preyed upon by tsotsis, who relieved them of cash or possessions.

Old East Bankers' narratives suggest that Red migrants were much more on the defensive in the 1950s than the trilogy's accounts suggest. The solidarity they forged in East Bank at this time may have had as much to do with the way they were treated in the city, as with their own desire to remain separate. The Mayers' failure to contextualise adequately Red migrant responses does leave the impression, as Moore notes, that Red identities and styles were always selected, cultivated and maintained as a matter of choice.40 The evidence of old East Bankers suggests that it was also the persistent and relentless victimisation of migrants that drove them into the defensive spaces of backrooms and yards in the wood-and-iron shack areas.

Home-made ethnography

How could the Mayers and their colleagues have failed to notice such seemingly obvious social and cultural dynamics? Did they not emphasise these popular cosmopolitan cultural forms because they were committed to clearing ethno-spaces that conformed to the dominant models in the discipline at that time? Or were there other reasons?41 Both the Mayers42 and Pauw43 explicitly denied that they were overly influenced by theoretical models, emphasising that their main aim was "simply to record" and present "first-hand factual knowledge" about urban African society. How in the process of "simply recording" could they have missed so much?

Several factors seem to be important here. Firstly, it should be noted that when the Xhosa in Town researchers first visited East Bank, the township was in political turmoil. In 1952, the locations erupted into political violence when police and army troops were deployed to quell political protests. During the unrest several whites were killed, including a Roman Catholic nun who lived and worked in the location. The political environment was still tense in 1954 when the Mayers and their colleagues started research on the Xhosa in Town project.

Unlike Monica Hunter, the Trilogy researchers lacked powerful local political allies within the location and had to rely heavily on the support of white clerics and officials. When I interviewed Philip Mayer in his home in Oxford in 1994 about the fieldwork methods they had employed in East Bank, he recounted their difficulties as white, non-Xhosa speakers from out of town with no local reputation, or any significant political connections. He also reflected that his work commitments at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, 160 kilometres away, precluded a sustained presence in the field. As the research project wore on, he was increasingly forced to rely on local research assistants to stand in for him, and to administer pre-designed questionnaires aimed at gathering information about household dynamics and social attitudes. He showed me some of the questionnaire schedules he had supplied to assistants as a means of gauging "urban commitment". They included questions about issues such as clan affiliation, frequency of home visits and religious beliefs, as well as migrant views about economic resources, such as fields and livestock. The structure of the questionnaires seemed to allow for the easy classification of respondents as either Red or School, without necessarily discovering how they classified themselves in different social contexts. Mafeje, who worked with Monica Wilson (formerly Hunter) in the 1960s, claims that their feeling at the time was that the categories of Red and School had been somewhat over-determined in the Xhosa in Town project.44

The use of questionnaires was also a key feature in Pauw's work. His research was based mainly on the administration of formal structured questionnaires, coupled with occasional field visits. He explained that:

Liberal use was made of the services of Bantu (sic) research assistants, but the author made a point of taking part in different phases of the fieldwork himself so as to be able to evaluate properly the information collected by assistants. Mr S.Campell Mvalo must be mentioned for having done the lion's share in collecting raw material ... Mr Enos L.Xotyani also gave assistance at various stages and his contribution of reports rich in detail was particularly valuable.45

In my interview with Philip Mayer, I was struck by the limited extent to which he and his colleagues had engaged in what some anthropologists call "deep hanging out",46 simply circulating in the research area, speaking to people informally and gathering information on an ad hoc basis. In retrospect, it appears that the Xhosa in Town researchers employed a two-pronged strategy, combining structured household interviews with attitudinal surveys generally conducted by their assistants. This is clearly evident in the text of Townsmen or tribesmen, where attitudinal information is often presented without close attention to biographical (life history) or situational context. The attitudes of migrants and townsmen often appear detached from their social and historical contexts, simply presented as apt illustrations of Red or School outlooks. This style of presentation also contributes to the over-determined distinction between Red and School. Consequently, Townsmen or tribesmen gives the reader very little sense of the blurred and complicated nature of the Red and School cultural categories in peo ple's varied everyday interactions. Rich and detailed as the Mayers' ethnography is of migrant life in the city, there is nevertheless a disjuncture: a sense of distance between the cognitive maps of migrants and embedded social and cultural practice. Such a disjuncture leaves an impression that "the cultural" and "the social" have been separated out, and only then mapped and overlaid onto each other.47

While there were similarities in the research methods of the trilogy and those of the RLI anthropologists, it is significant that the trilogy lacks any sustained analysis of public events and occasions of the kind seen in Mitchell's Kalela Dance. 48 One of reasons for this silence is related to the trilogy researchers' understanding of processes of cultural transmission. The assumption that seemed to underpin the project as a whole was that the transmission of culture essentially occurred as a domestic, inter-generational process, where learned behaviour was passed on from one generation to the next in situations of social intimacy. As a result it is perhaps not surprising that domestic groups and their local equivalents - the migrants' intanga (age-mate) groups and iseti beer drinking groups - emerged as the primary foci of analysis.49 The belief that the domestic domain was the critical and formative locale for the analysis of cultural transmission in the East London's politically unstable locations was clearly central to the spatial strategies the Mayers and their colleagues adopted as fieldworkers. It is indicative of the extent to which the trilogy's ethnographers confined themselves to the relative safety of peoples' homes and yards. Such spatial confinement blunted sensitivity to developments beyond the house, and especially to the changing cultural dynamics of the streets, dance-halls and other public spaces. By the same token, one of the main reasons for the comprehensiveness of the Mayers' account of amaqaba cultural forms and of Pauw's detailed account of the social dynamics of the matrifocal household, was that these forms were largely contained within the spaces of East Bank homes. In the case of the amaqaba migrants, the social stigma they carried in the location meant that they felt safest in rooms and yards where they could commune with home-mates (abakhaya).

In the case of Pauw's account of matrifocality, the situation was a little more complicated because single mothers or amakhazana often exerted considerable power and influence on the streets and in their neighbourhoods.50 The active involvement of these single, unmarried women in public life is seen not only in the fact that many of them ran businesses, but in their active involvement in public and political protests during the 1950s. Minkley claims that independent women virtually "owned the location" in the 1950s by virtue of their business acumen and influence in public affairs. He suggests that their capacity for independent social and political agency became a matter of grave concern to local Christianised location elites, who looked down on the practice of single mothering.51 On the basis of Minkley's account, it is difficult to understand how Pauw could confine his discussion of matrifocality to the home. One way of explaining this is in the light of the project's evaluation of the domestic arena as the primary site of cultural production and transmission. By his own admission, Pauw spent little time attending public events, visiting shebeens or standing around on street corners. The public roles, voices and agency of single women were generally beyond the reach of his "field".

Spatial circuits

How might a different spatial strategy have led the Mayers and their colleagues to different kinds of conclusions? In this section, I explore this issue by attempting to trace the circuits of connection between the house and other more public spaces such as the street, the veranda, the dance-hall, and beyond. Let me begin with the street.

The streets of the old East Bank location were created, at the turn of the twentieth century, as wide public thoroughfares associated with neatly fenced-off residential sites. But as the population of the location increased, people spilled out of their overcrowded houses and the streets emerged as important sites of public interaction and everyday community life. They became places of recreation, sites of contesting identities and reputations. The process whereby East Bank's residents claimed the streets was slow and geographically varied. As the location grew new streets were added, some outside the original grid pattern, making them and their associated neighbourhoods relatively invisible to the purview of officials. Areas like "Gomorrah" and "New Brighton" became infamous for their drinking houses, tsotsi gangs and prostitution, as well as for the absence of any official presence, as did Camp and Ndende Streets.

But it was not just everyday occupation of the streets that occurred. In some areas, older public thoroughfares were blocked off and the spatial layout changed with time. Ronnie Meinie gave a sense of the significance of his knowledge of the neighbourhood:

As it became very overcrowded, people had nowhere to build extensions to their properties, and this sometimes led them to build into the streets. You really had to know your way around, because some streets just came to a dead-end because people had built houses and rooms across them. In my case, you had to know that you couldn't get to Coot Street from Fredrick Street, where I lived, because there were dwellings in the way. It was like this all over. I remember clearly during the 1952 riots when we were running away from the police, how we would use these dead-ends and detours to trick them. We knew that they would not be able to get vehicles through in certain places and darted for those streets where the police would be trapped and have to turn back. This is how we played cat and mouse with them.52

The state's loss of control of the streets was one of the main reasons why white local officials increasingly insisted that the location be demolished.53

In connecting the space of the street to that of the house, the intermediate, almost liminal space of the veranda proved to be a critical conduit for transactions. The veranda constituted a sort of social membrane between street and house: between public exterior and private interior. In many East Bank homes, the front rooms were blocked off from the street by heavy drapes, while the front door was left open to allow access to the house's main living rooms. One reason for shutting off the street was that residents did not want officials surveying their house interiors from the street. With police raids a regular occurrence and families often harbouring "illegals", either as tenants or visitors, it was inadvisable for a house's interior to be visible from outside. The veranda thus became a space from which threats of raids and official surveillance could be monitored. Shouts of kobomvu (literally, "it is red") hailed out from slightly elevated verandas, warning people of impending patrols. The warnings were not only to assist the queens of larger shebeens and urban "illegals", they were also important for ordinary townsmen and women, travelling without one of the multitude of documents required by the state.

The veranda, usually above street level, was also a space from which women made their presence felt. East Bank's verandas can in some ways be likened to the Dutch window, which according to Cieraad, allowed women who were expected to remain indoors and attend to domestic pursuits, to extend their gaze and influence onto the street.54 In the East Bank, where female domesticity was not as spatially confined and women were generally more visible on the streets, the veranda proved to be an important site from which women could command a hearing. One former East Bank resident explained:

Women were always on the verandas, chatting and going about their business, but their eyes were on the street watching everything that was happening. They were always the first to know if a stranger was hanging around or whether something significant had happened.55

Other former residents remarked on how women would lean over the veranda and communicate with people on the street - other women or children at whom they were shouting. Washing clothes on the veranda allowed mothers and matriarchs to exercise surveillance of the street, while pursuing domestic chores. We were told that it was common practice in some areas that every morning before they left for school, the children of the house would collect two tubs of water, one for washing and one for rinsing, and leave them on the veranda for their mothers. It was also their job to dispose of the dirty water when they returned from school.

The veranda was also a space from which mothers and matriarchs created solidarities and extended their influence beyond the home. It was from here that independent women solicited migrants and lured men into their drinking houses. They also used the veranda as a relatively secure, albeit liminal, space from which to comment on, criticise and engage the street without having to occupy it physically. The veranda was also a space from which women could quickly disappear when threatened. It allowed them to be simultaneously on and off the street. Occupying the veranda was a statement of wanting to develop a street profile and presence. The veranda was, therefore, a critical conduit in allowing women to exert a presence on the street and to escape the confines of the house. But the veranda was also a contested space. Men and youths found they had to compete with women for the right to be there. Youths liked to sit on the veranda smoking and chatting. New musical groups sometimes practised on the verandas of houses, using them as a testing ground for artists with ambitions of making it to the Peacock Hall or the Community Centre.

Behind each house's veranda lay its more private space, not readily seen from the street. Despite the use of drapes to hide the interior of a home, the sharp distinction between the house and the street, between the private and the public (as noted by authors such as Cieraad in her account of nineteenth-century Dutch life), was not so evident in East Bank where overcrowding limited the capacity of households for privacy. Many wood-and-iron houses were extended by building backrooms to accommodate tenants. In some cases backrooms were allocated to extended family members, but more often than not they were rented to migrants for extra cash. Township rentals were high and proved to be a good source of income. The physical location of migrants in these backrooms, with their activities spilling out into the yards, created a distinction in many houses between front and back sections. The distinction between migrants and townsmen in East Bank of the 1950s was thus often a distinction between front and backrooms - home owners generally used front rooms, while migrants lived in backyards. Backroom-living was always more acceptable for migrants than living on the street front. As the Mayers describe, it was in those yards where migrants gathered to socialise over weekends and iseti beer drinks took place.56

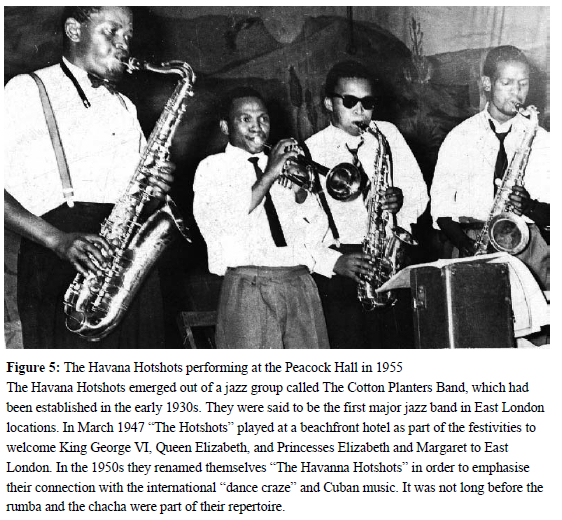

The other key circuit of public power and cultural exchange was one that connected the community halls, sports grounds and other recreational areas to the street. Productions of regular musical, dance, sports and entertainment events at places like the Peacock Hall, the Community Centre and the Rubusana Sports Grounds made these important sites for cultural production and performance. They emerged as definitive spaces in the construction of cosmopolitan styles, fashions and an East Bank economy of prestige. People from East Bank, West Bank and North End socialised and engaged in competitive style-making. Rubusana Park and the Peacock Hall were particularly significant, the former because it was the city's major sports venue for blacks, the latter because it was the main live music venue for East Bank, West Bank and North End residents. Given the limited access location residents had to public space in the white city, they made the most of their segregated public facilities, by hosting a wide range of events that drew massive popular support. One former East Bank resident remembered that, "if you wanted to hire the Peacock Hall you would often have to wait more than a year for a booking."57 The venues' annual calendars were full of public events and carnivals: Santa Day, the Bat Fair, the Hobo Show, Mfengu Day, music concerts, fêtes, ballroom and other dancing competitions, and sports tournaments. Rugby was the main sports activity and there were teams such as Swallows RFC, Winter Roses, Black Lions, Storm Breakers, Bushbucks, Tembu United, Early Roses, Busy Bees and the Boiling Waters (Ayabila), each with their own following. Great excitement marked meetings of rival teams.

Spaces outside the township, such as the city centre, the West Bank racetrack and beaches, became focal points for socialising and style-making. Mrs Majavu explained:

The thing that made the beach such a wonderful place for us was that it was out of the location. It was not cramped. There was open space, clean air and the sea all around. The beach was especially popular on Sundays after church when we used to pack a picnic and go down there for the day. It was really great fun. It gave the young guys a chance to check out the girls and for people to meet old friends and socialise . You can imagine what a shock it was when the apartheid signs went up: "Whites Only - Net Blankes."58

Analysing such events, Arjun Appadurai coined the term "tournaments of value".59 Using the classic anthropological example of exchanges of prestige goods in the Trobriand kula rings, Appadurai suggests that "tournaments of value" be seen as "complex periodic events that are removed in some culturally defined way from the routines of economic life."60 He argues that they contain a "cultural diacritic of their own"61 and are involved not only with the quest for status, rank, fame and reputation among different actors, but the disposition of the central tokens of value in a given society. This is seemingly how sports, dance, music, beach or cinematic events were constituted in East Bank during the 1950s. They created an air of expectation and exhilaration, especially when top local bands like the Bright Fives, the African Quavers, the Bowery Boys, the Havana Hotshots or one of many other local bands were performing. As new styles and influences came into circulation in the dance-hall, for example, so they found their way onto the streets through imitation and alteration.

Appadurai uses the concept "diversions" to explore the ways that the politics of value is domesticated, appropriated and altered to carve its way along different paths of value and meaning. This concept is useful for trying to make sense of how the dance-hall, the beach and sports stadiums were connected and re-connected to the street and the house. It invokes Hannerz's notion of creolisation as a complex marriage of cultural flows and transactions between various spatially defined sites of cultural production, as well as between locations and wider cultural processes.62

In terms of an understanding based on the application of these ideas, the emergence of cosmopolitan styles in East Bank was clearly more than a simple imitation of western cultural forms. It necessarily involved an active process of cultural appropriation and reworking. As new fashions, styles and cultural forms went on display at these "tournaments of value", so they were absorbed, appropriated and reworked to create new constellations of value and meaning for the streets.63 The cultural circuits created between the streets and the dance-hall enabled a constant process of appropriation, re-appropriation and transformation, as cultural forms and styles moved back and forth, blending cosmopolitan and local elements along the way. Pule Twaku commented:

We were always watching out for something new, where the style was going. Like when the Vikings came first to the Peacock Hall in their gangster style. Suddenly, everyone was checking them out and it was not long before other youths on the streets were trying to imitate them. The same happened with the Panama hats . it was a fashion for a time, then people got tired of it and looked for something new.64

Another example of the local re-appropriation of culture was the way in which tsotsi youth would imitate the villains they encountered in B-grade American movies and strut their styles on the streets.

Conclusion

In the above discussion I have tried to show that there was more local engagement with cosmopolitan styles and cultural forms in East London's locations than the trilogy was able to reveal. In fact, I have argued that the failure of these studies to acknowledge and reflect on the intensity and extent of local-level involvement with transnational social and cultural influences is one of the major weaknesses of the trilogy. Unlike others who have commented on this work, I have not focused here on the political and theoretical motives of the authors as much as their methodological orientation. In relation to the latter, I have suggested that the studies comprising the Xhosa in Town trilogy were all essentially "home-made" ethnographies, in the sense that the bulk of the fieldwork and interviews took place inside or around the space of the home. Philip Mayer clearly believed that a strong focus on the domestic domain would provide key insights into the cultural dynamics of urbanisation in East London. What Mayer and his colleagues failed to explore was that the space of the house, the rented room and the yard figured very differently in the social lives and cultural experiences of different categories of urban dwellers in East Bank. In the case of migrants, especially the frugal Reds, the space of the rented room and yards formed a primary node of socialising, drinking and relaxation.

If the rented room and backyard were focal points of migrant social lives in the city, this was certainly not the case for the majority of urban-born youth and men, who preferred to socialise on the verandah, on street corners, in local shebeens, dance halls and tea-rooms. Given the social profile of the "borners" and the location of their preferred leisure activities, it is difficult to understand why Pauw decided to use household surveys and family analysis as the basis of his account of the cultural orientations of the so-called "second generation". When compared with the rich and detailed ethnography of migrant lives found in Townsmen or tribesmen, Pauw's Second Generation appears ethnographically thin and unconvincing. The problem for Pauw was that so little of what he needed to see and experience in order to develop a fuller analysis of urban cultural life amongst the "second generation" was simply not visible to him. In order to tap into the dynamics of non-migrant lifestyles and identities, offering the same level of ethnographic detail and insight as Townsmen or tribesmen, he would have had to adopt a very different fieldwork strategy: one that engaged with extra-domestic spaces.

Had Pauw and the Mayers adopted a less domestically focused approach, they might have arrived at rather different conclusions. Greater exposure to the multiple public sites of cultural production and performance would not only have alerted them to the enormous power and influence of cosmopolitan cultural styles in the location, but also of the relational dynamics of identity politics in the city. By focusing on the domestic domain, the researchers were well placed to provide social and cultural content to the categories of Red and School, but not to reflect in any detail on how different cultural styles and orientations were pitted against each other in struggles for space and power in the location.

Finally, it is worth noting that, despite the heavy criticism of the Xhosa of Town project, the "home-made" ethnographic tradition that underpinned it remained popular in the new Marxist-inspired anthropology of the 1970s and 1980s. As questions of culture and identity faded into the background, a new generation of anthropologists turned their attention to the micro-political economy of households in rural villages and bantustan resettlement camps.65 This work had many virtues and offered critical insights into the devastating social and economic consequences of migrant labour. Yet it also kept anthropologists out of the cities, and pegged them back within the space of the house. Admittedly, by the late 1980s there was growing interest in ethnicity and the deconstruction of apartheid categories, but for many of those in the field, the primary methodological orientation of the discipline was still towards "housework". In the post-apartheid period, this image of anthropologists as "houseworkers" has been taken up by the development sector, who have looked to anthropologists to report on "local impacts" and "demand-side dynamics" of new development policies. The methodological tendencies, which I have criticised in the Xhosa in Town project, are thus deeply embedded within the fieldwork practice of South African anthropology.66

1 Thanks to the Dutch-funded research programme SANPAD for supporting this research. I am also grateful to the editor of this journal for insightful comments on earlier drafts. I also wish to thank my colleagues at the ISER, especially Gary Minkley, Mcebisi Qamarwana, Adrian Nicholas and Anne King, for their support, as well as Landiswa Maqasho who worked with me as a co-researcher on the East and West Bank Land Restitution Claims.

2 See especially T.Asad, ed., Anthropology and the colonial encounter (London, 1973) and more recently T.Erikson and F.Nielsen, A history of anthropology (London, 2001).

3 For an analysis of the shift, see L.Bank, 'Xhosa in Town revisited: From urban anthropology to an anthropology of urbanism' (Ph.D., University of the Cape Town, 2002), 9-25; also W.Beinart, 'Speaking for themselves' in A.Spiegel and P.McAllister, eds., Tradition and transition in southern Africa (Johannesburg, 1991), 15-17.

4 See L.Bank and L.Maqasho, 'West Bank restitution claim: A social history report', ISER Research Report 7, Rhodes University, 2000; L.Maqasho and L.Bank, 'East Bank restitution claim: A social history report', ISER Research Report 9, Rhodes University, 2001.

5 G.Wilson, 'An essay on the economics of detribalization in Northern Rhodesia', Rhodes Livingstone Paper, No. 5-6, 1941-42, Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, Livingstone.

6 J.Ferguson, Expectations of modernity: Myths and meanings of urban life on the Zambian Copperbelt (Berkeley, 1999). [ Links ]

7 Ibid., 24-37. See also R.Brown, 'Anthropology and colonial rule: Godfrey Wilson and the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, Northern Rhodesia' in T.Asad, ed., Anthropology and the colonial encounter (London, 1973); R.Werbner, 'The Manchester School in south-central Africa', Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 13, 1984; L.Schumaker, Africanizing anthropology: Fieldwork, networks, and the making of cultural knowledge in central Africa (Durham, 2001).

8 M.Gluckman, 'Tribalism in modern British Central Africa', Cahiers d'Etudes Africaines, vol. 1, 1960, 55. [ Links ]

9 Ferguson, Expectations of modernity, 20.

10 P. Mayer, 'Preface' in B.Pauw, The second generation: A study of the family amongst urbanised Bantu in East London, xvii.

11 Ibid.

12 Mayer, Townsmen or tribesmen, 10-30.

13 Mayer used the term "incapsulation" to refer to the process by which Red migrants maintained their rural home ties in the city by restricting their fields of social interaction to an all-Red circle in town, comprised mainly of close kin and abakhaya (home mates). These patterns of social interaction allowed Red migrants to keep up an unbroken nexus with the rural home and to restrict their social interactions in the city. Ibid, 91-110.

14 Pauw, The second generation, 170-74.

15 J.Clifford, Routes: Travel and translation in the late 20th Century (Cambridge, 1997), 201-205.

16 Quoted in A.Gupta, and J.Ferguson, 'Discipline and practice: "The field" as site, method and location in anthropology' in A.Gupta and J.Ferguson, eds., Anthropological locations: Boundaries and grounds of a field science. (Berkeley: 1997), 21; also U.Hannerz, Cultural complexity: Studies in the social organization of Meaning (New York, 1992).

17 M.Hunter, Reaction to conquest: Effects of contact with Europeans on the Pondo of South Africa (London, 1936). [ Links ]

18 Ibid., 455.

19 Ibid., 437.

20 Ibid., 437.

21 Ibid., 455.

22 Ibid., 467.

23 Walter Benson Rubusana was born in Mnanadi in the Somerset East district in 1858. He attended Lovedale College and in 1884 was ordained in the Congregational Church and became a minister in the East Bank location. Rubusana played a significant role in the early politics of the African National Congress and remained active in ministry and politics until his death in East London in 1936 (Daily Dispatch, 10 June 2001).

24 See T.Lodge, 'Political mobilisation during the 1950s: An East London case study' in S.Marks and S.Trapido, The politics of race, class and nationalism in twentieth century South Africa (London, 1987), 322-335.

25 I take this term from J.Kahn, who makes an interesting distinction between the "high or avante garde modernism", associated with sophisticated aesthetic and intellectual elites - the educated middle classes - and the "popular modernism" embraced by ordinary people which is mediated through the entertainment industry and modern social movements. The key point Kahn makes in relation to "popular modernism" is that its mass appeal should not be mistaken for a lack of critical content. See J.Kahn, Modernity and exclusion (London, 2001).

26 Kenny Jegels, Interview, East London, 20 March 2000.

27 M.Chapman, The Drum decade: Stories from the 1950s (Pietermaritzburg, 2001), 187.

28 See D.Coplan, In township tonight: South Africa's black city music and theatre (Johannesburg, 1985); C.Glaser, Bo-Tsotsi: The youth gangs of Soweto, 1935-1976 (Cape Town, 2000); U.Hannerz, 'Sophiatown: The view from afar' in K.Barber, ed., Readings in African popular culture (London, 1997); D.Mattera, Memory is the weapon (Johannesburg, 1987); C.Themba, The world of Can Themba. (Johannesburg, 1985).

29 Interview, East London, 28 January 1999.

30 Interview, East London, 22 September 1999.

31 Glaser notes that the term "tsotsf only emerged on the Reef in 1943-1944, and referred to a style of narrow-bottomed trousers that became popular amongst the urban youth. As the style evolved, it became associated with its own hybrid language, tsotsitaal. The term seems to derive from the Southern Sotho word ho tsotsa, which means "to sharpen". The current meaning of tsotsi in South Africa associates this category more with crime than with fashion and style. See Glaser, Bo-tsotsis, 47-52.

32 For further discussion of studio photography in the East Bank location in the 1950s, see M.Qamarwana, 'Modernity and development in East London's locations' (BA Hons thesis, Rhodes University East London, 2002).

33 Interview, East London, 10 September 2000. Glaser makes a distinction between the high-profile "hot-shot gangs" and "street-corner gangs" on the Reef in the 1950s. In East Bank, the Vikings were the local equivalent of a "hot-shot gang" as they dominated the location and held sway over many of the small-time street gangs in the 1950s. See Glaser, Bo-Tsotsis, 78-86.

34 Group interview, East London, 14 May 2001.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Compare L.Ntsebeza, 'Youth in urban African townships, 1945-1992: A case study of the East London townships' (M.A. thesis, University of Natal, 1993).

39 Interview, East London, 21 August 2001.

40 S.F. Moore, Anthropology and Africa (Charlottesville, 1994), 58. [ Links ]

41 Clifford, Routes: travel and translation in the late 20th century.

42 Mayer, Townsmen or tribesmen, 319.

43 Pauw, The second generation, 230.

44 See A.Mafeje, 'Who are the makers and objects of anthropology?', 1; also M.Wilson and A.Mafeje, Langa: A study of social groups(Cape Town, 1965).

45 Pauw, The second generation, 230.

46 R.Rosaldo, Culture and truth: The remaking of social analysis (Boston, 1989).

47 This is, of course, not to suggest that Red and School were not fundamental categories in the classificatory schemes of migrants and urban residents in East London in the 1950s. See D.Fay, 'A place where cattle get lost: Rural and urban transformation and the salience of the Red/School division among Xhosa in East London in the 1950s', Unpublished paper, Boston University, 1996.

48 C.Mitchell, The kalela dance (Manchester, 1956).

49 See L.Malkki, 'News and culture: Transitory phenomena and the fieldwork tradition' in A.Gupta and J.Ferguson, eds., Anthropological locations(Berkeley: 1997).

50 Pauw, The second generation, 141-165.

51 G.Minkley, '"I shall die married to the beer": Gender, family and space in the East London locations, c1923-1952', Kronos, vol. 23, 1996, 135-157.

52 Interview, East London, 10 September 2000. D.Crouch, 'The street in the making of popular geographical knowledge' in N.Fyfe, ed., Images ofthe street (London, 1998), 60-85.

53 Compare E.Nel, 'The spatial planning of racial residential segregation in East London, 1948-1973' (M.A. thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, 1990).

54 Cieraad argues that the emergence of window prostitution in Holland was a product of women asserting their agency through the space of the window to solicit men outside. See I.Cieraad, 'The Dutch window' in I.Cieraad, ed., At home: An anthropology of domestic space (Syracuse: 1999).

55 Group interview, East London, 30 May 2001.

56 Mayer, Townsmen or tribesmen, 111-124.

57 Mr Foster, Interview, East London, 20 October 2000.

58 Interview, East London, 18 November 1999.

59 A.Appadurai, 'Introduction' in A.Appadurai, ed., The social life of things(Cambridge, 1986).

60 Ibid., 21.

61 Ibid., 21.

62 U.Hannerz, 'The world in creolization', Africa, vol. 57, 1987; U.Hannerz, Cultural complexity: Studies in the social organization of meaning (New York, 1992).

63 See also K.Hansen, Salaula: The world of secondhand clothing in Zambia (Chicago, 2000).

64 Group Interview, East London, 14 May 2001.

65 See R.Gordon and A.Spiegel, 'Southern African anthropology revisited', Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 22, 1993; also D.James, 'Anthropology, history and the making of past and place' in P.McAllister, ed., Culture and the commonplace: Anthropological essays in honour of David Hammond-Tooke (Johannesburg, 1997); J.Kiernan, 'David in the path of Goliath: Anthropology in the shadow of apartheid' in P.McAllister, ed., Culture and the commonplace (Johannesburg: 1997).

66 For further discussion, see L.Bank 'Xhosa in Town revisited: From urban anthropology to the anthropology of urban-ism', 260-72.