Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.98 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2008

ORIGINAL ARTICLES

HISTORY OF MEDICINE

Dr James Barry: The early years revealed

Hercules Michael du Preez

MB ChB, FRCS; Constantia, Cape Town; Michael du Preez worked in private urological practice and teaching hospitals in Cape Town from 1968 to 1993 and spent most of his latter career at a Military Hospital in Saudi Arabia until his retirement in 2001. His other interests include yachting (racing, a transatlantic crossing in his ketch and cruising in Turkish waters), horticulture, music, photography, breeding Chow Chows, travel, fine art, antiques and silver. Since retirement his researches have included setting Dr James Barry's record straight, and the journals of Captain John Strover of the Indiaman, ESSEX

ABSTRACT

The extraordinary story of Dr James Barry still excites interest and controversy over one hundred and forty years after her death.1-5 Dr Barry's army career has been well documented,6 but her early life has remained obscure and subject to speculation.7-9 This study advances some ideas previously presented,10-12 and from a substantial collection of contemporary manuscripts13 reconstructs an important part of Dr Barry's early life.

Background

James Barry emerged, seemingly from complete obscurity, as a medical student at Edinburgh University late in 1809, graduating MD in 1812. Following six months as a Pupil at St Thomas', the young doctor was examined at the Royal College of Surgeons and in July 1813 recruited into the army. A period at York Hospital, Chelsea, and the Royal Military Hospital, Stoke, Plymouth, was followed by promotion and service abroad for a long, distinguished and at times controversial career. During a final posting to Canada in 1857, the health of the ageing doctor failed, and to his annoyance14 he was boarded on half pay in 1859. He died in London on 25 July 1865, the last straw probably being dysentery or cholera, which was then raging in the city.

Sophia Bishop, the maid of the household where Dr Barry was lodging, laid out the body, and made the startling discovery that the late Inspector General had been 'a perfect female'.15 By the time this unwelcome fact became known to the army, the mortal remains had already been buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, having been accorded a military funeral. There were no known relatives. No postmortem was performed, as the cause of death appeared unremarkable. The sex of the deceased had not then yet been cast into doubt, but Sophia Bishop's later revelation excited much attention and controversy and continues to do so. Dr Barry is remembered for this sensational fact rather than for the real contributions that she made to improve the health and the lot of the British soldier16 as well as civilians.17,18

Scope of the present research

Much written about Barry's early life has not been substantiated from primary sources, but, through frequently repeated speculation, has acquired the simulacrum of truth.19 My main purpose was therefore to establish and document clear historical facts, using early 19th century records from the army and other institutions in addition to wider sources. Available for study was a large, important and unique collection of contemporary letters, legal documents and financial papers, previously thoroughly researched by Pressly in the context of James Barry (1741 - 1806), the artist24,25 and uncle of Margaret Bulkley, the girl who became known as Dr James Barry. My investigation focuses on the niece and reveals a great deal about her early years. I will refer to the young teenager, Margaret Bulkley, using the feminine gender but will use the masculine after she adopted the male persona of James Barry.

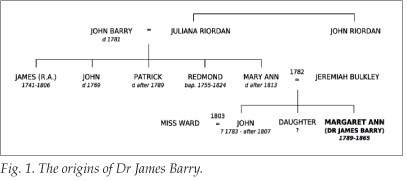

The origins of Dr James Barry (Fig. 1)

Little is known about the patriarch of the Barry family, John Barry (d. 1781), except that he materialised26 in 18th century Cork, first as a builder, then a publican, the owner of a small coastal shipping business,27 and finally a small-time landowner. He married Juliana Ann Riordan. Their first child, born on 11 October 1741, was James, who subsequently became the artist and Royal Academician,28 followed by John (d. 1769), Patrick (d. between 1789 and 1803), Redmond (1755 - 1824) and their sister, Mary Ann, whose year of birth is not known. Mary Ann married Jeremiah Bulkley in 1782.30 He was seemingly decent but naïve, was in the grocery trade and held a small government post in the Weigh Houses of Cork. They lived on Merchant's Quay31 on the River Lee in Cork.

The Bulkleys had three children. John, whose fecklessness and selfishness brought about the family's woes, was probably born in about 1783; Margaret Ann, the subject of this paper, was born in 1789;32,33 and there was another daughter,34,35 about whom nothing more is known.36 Things went well for the Bulkleys until it was time to set John up in a career. At considerable expense, he was apprenticed to an attorney in Dublin, but became infatuated with a Miss Ward, 'a young Lady of genteel connexions'.37 Perceiving an opportunity to marry up, John demanded a substantial settlement for his future wife from his father, including the purchase of a farm. They married in 1803, but the cost, £1 500, effectively ruined the Bulkleys.38 Jeremiah ended up in the Marshalsea in Dublin, and Mary Ann and Margaret found themselves destitute, 'Thrown out of house & home by a Husband & Son'. Mrs Bulkley was faced either with starvation or trying to earn some kind of living, for which she chose to be in London.39

Mary Ann Bulkley pleads with her brother for help

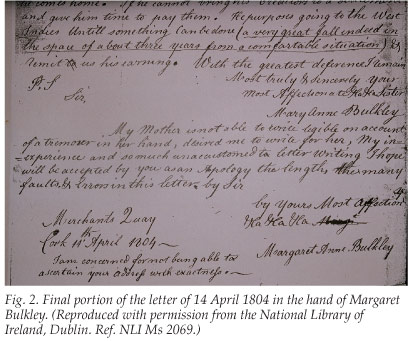

Despite Mrs Bulkley not having seen or written to her brother, James Barry, for thirty years or more,40 he was the only person to whom she could turn for help. From Merchant's Quay, Cork, she dictated a letter to him on 11 April 1804,41 recounting the sorry tale of the family's misfortunes, but there was no direct request for money - she knew him too well for that. The postscript is of particular significance (Fig. 2): 'My mother is not able to write legible on account of a tremor in her hand, desired me to write for her,' which is a confirmed example of the handwriting of Margaret Bulkley at the age of about fourteen or fifteen. This immature hand serves as an invaluable comparison with twenty-six later examples of Margaret's handwriting, including the first letter she wrote bearing the signature 'James Barry', dated 14 December 1809.42 A representative selection of these letters has been subjected to document analysis43 and combined with other evidence conclusively established the identity of Dr James Barry, leaving no doubt that the doctor started life as Margaret Ann Bulkley.

Nine months after this correspondence commenced Mrs Bulkley and Margaret were in London, when a second letter, with a different tone, was penned to the artist.45 They had been in London about two months following the April 1804 letter, and Margaret had seen her uncle, possibly for the first time. He had offered her a less than warm welcome, as his sister complained: 'What did you give my Child when she was here last June, did you ask her to Dinner, in short did you act as an Uncle or a Christian to a poor unprotected unprovided for Girl who had not been brought up to think of Labor and, Alas! whose Education is not finished to put her in the way to get Decent Bread for herself & whose share has been given to a Brother.'

This sentence explains two related matters. Margaret enjoyed little in the way of prospects and needed to complete her education to earn a living. With no fortune, and from her aspirational middle-class background, marriage would be difficult to achieve, especially as she was 'unprotected', having no influential male friend or relative.

Mrs Bulkley also stated:46 'Margaret being but 15 years Old & of course not of Age ...', which helps to establish that Margaret's year of birth was probably 1789, about which there has been much speculation and misinformation, the latter disseminated not least by herself.47 The letter goes on: 'You ask why I came to London, Sure Sir you could not Deceive yourself so much as to think I came to Beg from you...', and later: 'it was to see you after a period of more than 30 years to see if there was one relation of whom I may ask advice in the World but Disappointment has attended that ...'. Mrs Bulkley proposed a legally dubious and not strictly honest proposition to her brother to help retrieve some of the family property for Margaret's ultimate benefit. He declined, but to judge from later correspondence50 the old curmudgeon possibly relented and had second thoughts about a property in Cork, and seems also to have been stirred into action in respect of Margaret's education.

Margaret Bulkley's London education

While James Barry appeared not to have much money, he possessed a circle of loyal and influential friends, most of whom shared his liberal or even radical ideas and tolerated his eccentricities. Subsequent events lead one to conclude that he discussed Margaret's education with two men who could help: Dr Edward Fryer,51 an academically inclined physician, and General Francisco Miranda, a Venezuelan revolutionary, no less.55 My sense is that they evolved a plan for Margaret at some time between 14 January 1805 (the date of Mrs Bulkley's second letter) and 31 August 1805, when the General sailed off on his first effort to liberate Venezuela from the Spanish Crown. Whether the idea was to educate her to be able to earn a living as a teacher or governess, as envisaged by Mrs Bulkley, or whether Miranda's vision of a medical career for her in his new Venezuela was part of a grander scheme, is unlikely ever to be known. The former seems the more likely.

On 22 February 1806, after a short illness, James Barry died60 leaving no will. His possessions were auctioned and the proceeds of £724.15/- 65 divided equally between Mrs Bulkley and her only surviving brother, Redmond, who had emerged from a prison ship at Portsmouth, where he was either working or living as an invalid.65 Fortunately for posterity, other less obvious assets of cash and investments amounting to £2 40066,67 found their way into a special fund for Margaret.68 After her brother's death, Mrs Bulkley and her daughter returned from Cork to London and remained there for three and a half years, until their departure for Edinburgh at the end of November 1809.

Money appeared to be tight, however, and on 19 May 1806, writing from 12 Brook Street (now Stanhope Street), Margaret was trying to obtain a post, presumably as a teacher, in the household of a '... Lady at Camden Town. Mr. Reardon [the family's long-suffering solicitor] will himself perceive the sooner that Miss B - can be placed there would be better. General Miranda's Address is Grafton Street Fitzroy Square.'69 Days after arriving in London, Margaret was making use of the General's 'very extensive and elegant Library',70 and endeavouring to augment her income. This part-time teaching was referred to in a much later letter from Jeremiah Bulkley, then still in Dublin.71,72 Margaret and her mother lodged at several addresses in London, all within easy walking distance of Dr Fryer's and General Miranda's residences, suggesting that lessons could have taken place at either or both houses. The General's library would have provided an ideal milieu for study. With its huge collection of books,69,73-75 appropriate to the acquisition of a liberal education,76,77 and with Dr Fryer's qualities as a tutor, Margaret Bulkley was exceptionally well positioned to benefit.

The teenager was also exposed to other influences. Miranda returned to London early in 1808, after unsuccessful efforts to liberate his country. He had every opportunity to pass on his enlightened ideas and his idealistic visions to the diligent pupil. Others with similar views who had been in the late James Barry's circle included William Godwin, the widower of Mary Wollstonecraft, whose Vindication of the Rights of Women had been published in 1792. Godwin, who also held radical ideas, had been a close friend of the artist.78 Miranda himself would have been able to observe how remarkably well Margaret had benefited and matured after just two years of further education. It would not have been surprising if the grand idea had emerged of putting the nineteen-year-old through a medical education, to enable her to participate in his vision for the future Venezuela.79 This would have introduced an entirely new dimension to the modest educational goals expressed in Mrs Bulkley's letter of January 180580 - nothing less than three years' study at a medical school. This raised another hurdle, as she would then be obliged to take the extraordinarily bold step of altering her appearance and her persona to that of a young man and sustaining the deception until after the final examinations. In the early 19th century only men were admitted to the medical schools in Britain,81 and discovery of the sex of the young medical student would have ruined any chance of success. The plan for Margaret's education had now become far more ambitious and assumed the dimension of a conspiracy, party to which were Mrs Bulkley, Margaret, Dr Fryer, General Miranda and Daniel Reardon, the solicitor. If this construct is correct, the young doctor could have resumed her female identity once qualified and on her way to Caracas, Venezuela. However, events took an entirely different turn. Sadly, in the summer of 1812, at about the time James Barry the medical student was undertaking the final MD examinations, General Miranda was cruelly betrayed by his protégé Simon Bolivar82 and imprisoned by the Spanish; he remained incarcerated until he died of typhus, in Cadiz, on Bastille Day, 1816.83 Thus the Venezuelan dream came to nought, and the newly qualified Dr James Barry was obliged to address a new and daunting reality. The difficult choice was either to reveal her identity and be confronted by a highly problematic future, or to continue with the masquerade as a man. Dr Barry made the second choice. She carried it off brilliantly, joining the army (quite possibly with the assistance of Lord Buchan, another friend and patron of her late uncle), rising through sheer ability to high rank, and successfully concealing her identity to her dying day, an astonishing duration of fifty-six years.

The voyage to Leith

Buried within the Barry family albums was the surprising discovery that Mrs Bulkley and her daughter travelled to Edinburgh not by stagecoach, but by sea.84 There was an active and successful passenger boat service between Wapping and Leith from the early 1790s85,86 until the railway eventually reached Edinburgh.

In a Statement of Account headed 'Drs. Mrs. Bulkley & Miss Bulkley in Account with Daniel Reardon & Co'87 and dated 3 April 1810 appears an item '1809 Nov 28 To cash to you on going to Scotland by my Brother £10 -//~'. This clearly helps to establish when the pair left for Edinburgh.88,89

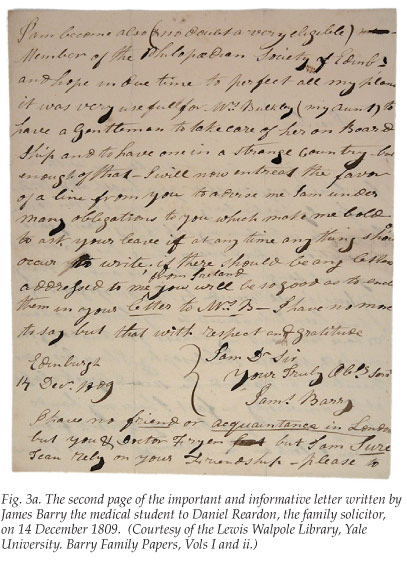

Later, writing to Daniel Reardon as James Barry,92 the new medical student stated: '... it was very usefull [sic] for Mrs. Bulkley (my aunt) to have a Gentleman to take care of her on Board Ship and to have one in a strange country...'(Fig. 3a).

This remarkable revelation clearly reveals when the metamorphosis of Margaret Bulkley into James Barry took place. The pair are likely to have left by coach from their lodgings at 27 Charles Street (now Drummond Street), boarding the smack at Miller's Wharf, Wapping, with Margaret already dressed as a man. Embarking as a woman and later appearing on deck in men's clothes would have been imprudent, a change the details of which would soon be doing the rounds in Edinburgh. Taking on the appearance of a young man would therefore have taken place beforehand, probably on 29 or 30 November 1809.

The disappearance of Margaret Bulkley and the appearance of James Barry

Margaret Bulkley's erasure from the pages of history was carefully planned. She might be recognised in London but was unknown in Edinburgh, and it was essential that it should remain so. Assuming the identity of a nephew of both James Barry, the artist, and of Mrs Bulkley, the young medical student appeared to have conjured up another brother for James, John, Patrick, Redmond and Mary Ann; a fictitious putative father whose son he would appear to be. With John long dead, James recently dead (and unmarried), and Patrick presumed dead, and bearing in mind the disreputable career of Redmond, he was unlikely to have chosen any of them for the role.

Furthermore, in the letter to Daniel Reardon,96 it becomes clear that nobody, apart from the solicitor himself, the General and Dr Fryer knew about the move to Scotland. Barry, by now 'he', requested that any correspondence, especially from Ireland, should not simply be readdressed to Edinburgh (for obvious reasons); any such mail should be enclosed within a new cover and addressed to Mrs Bulkley. Letters from Reardon himself could be addressed to James Barry, Student, University, Edinburgh (Fig. 3a). On the same day (14 December 1809), Mrs Bulkley also sent a letter to Daniel Reardon:97 '. it is not necessary to be very minute in telling anyone where I am, but to say to them (especially any of my Irish friends) when you hear from me, if the[y] have any thing to say, you'll let me know'. And on 11 May 1810: 'It is not at all necessary to give my address to any of my friends English or Irish, as I do not like to [be] harrassed with letters ...'.98

On 7 January 1810,99 Barry wished General Miranda '... very many happy returns of the new year in which Mrs. Bulkley (my aunt) joins with me'. The postscript also asks 'If you should favor me with a line please to [send] to James Barry, Student at the University, Edinburgh. * [sic] As Lord Buchan nor anyone here knows any thing about Mrs. Bulkley's daughter, I trust my dear General, that neither you nor the Doctor [Fryer] will mention in any of your correspondence any thing about my Cousin's friendship & Ca for me.' Then there was the unanswered previously mentioned letter (dated 27 November 1809) from Jeremiah Bulkley to Margaret which was written just days before the embarkation.100 It would have been much to the disadvantage of the new James Barry for his father to know of his whereabouts or about the startling new career he had just commenced. With the exceptions of Fryer, Miranda and Reardon, the two had severed all connections with friends and family.

The medical student at Edinburgh

On 14 December 1809, nine days after arriving at Edinburgh, James Barry wrote to Daniel Reardon:101 '. indeed every thing has far exceeded my most sanguine expectations and Mr. Barry's Nephew is well received by the Professors &ca. I have been introduced to my Lord Buchan & have taken out my tickets for Anatomy, Chemistry and Natural Philosophy. I have been metriculated [sic] and attend the second Greek class at the University in fact I have my hands full of delightfull business & work from seven oClock in the morning till two the next ...'

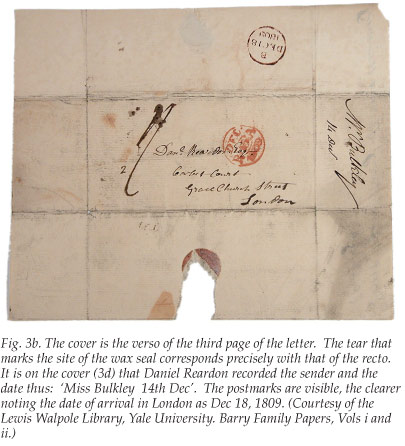

This letter is the first to be signed James Barry, confirming that Daniel Reardon was party to the conspiracy. Yet on the outside of the cover, the ever-meticulous solicitor has noted the name of the sender and the date of the letter, recording: 'Miss Bulkley, 14th December' (Fig. 3b), despite the letter being signed 'James Barry'. It is thus possible beyond any doubt to identify the individual who was to become Dr James Barry, neatly confirming the result of the handwriting analysis - a particularly significant discovery.

The matriculation ceremony, costing half a crown and involving the signing of the Matriculation Album,102 admitted the student to the privileges of the University, and permission to use of the Library.98 While there was no set curriculum for the three-year period of study, courses in certain subjects were obligatory,99 including Anatomy (and Surgery) and Chemistry, Medical Theory and Practice, Materia Medica and Pharmacy and Botany. It was also necessary to attend clinical lectures at the Royal Infirmary. Barry completed all the prescribed courses required to present himself for the MD examination. It is worth while noting here that Rae mistakenly misinterpreted one document, stating that Barry undertook '18 Courses in Chemistry and 12 Courses in Botany'103 - a manifest impossibility. The numbers quoted referred to lectures rather than courses, but the error has unfortunately been repeated in subsequent derivative works.

The final examinations for Doctoratus in Arte Medica

Only about 20% of medical students at Edinburgh ever graduated.104 James Barry's graduation took place in July 1812; fifty-seven other students also were successful that year.105 The graduation fee of twenty-five pounds, raised from the thirteen guineas it had been in 1809, was a substantial sum. The process106 had started three months earlier, in May 1812. After informing the Dean of the intention to be examined, providing certificates of attendance and paying £10 (to be divided among the six examining professors), the procedure (entirely in Latin) got under way. (Barry was unlikely to have needed a Latin coach, as owing to the earlier efforts of Dr Fryer,107,108 Latin would not have presented difficulties.) The first examination was oral, held somewhat informally and in private, to put the candidate at ease and to judge whether he should be allowed to proceed further. A later oral examination, held in the University Library, was followed by a written examination, traditionally commenting on aphorisms of Hippocrates, as well as case histories. Finally there was the thesis, resembling today's dissertations but both written and defended (publicly) in Latin.109 It was described as exactly that, Disputatio, or discussion, at the top of the title page (Fig. 4). Barry had started work on the thesis during the previous summer, when staying at Dryburgh Abbey, the seat of Lord Buchan. The kindly Earl wrote to Dr Anderson, his friend in Edinburgh, on 15 October 1811: 110,111 'James Barry ... has been here for five weeks past and has employed himself in my library very busily in usefull reading of Books connected with his professional views. He is a well disposed young man and worthy of yr. notice and advice in his studies. It will be kind of you and Dr, Irving [the son in law of Dr Anderson] to look at the Latinity of his Thesis which he tells me he is about to prepare this winter, & 'tho he is much younger than is usual to take his Degrees in Medicine and Surgery yet from what I have observed likely to entitle himself to them by his attainments. He means to go by invitation of General Miranda to the Caracas.'

The thesis113 also signals certain anchoring details in the life of the young graduate, facts first recognised by Isobel Rae.117 The name he assumed, James Miranda Steuart Barry,118 reflects the debt of gratitude acknowledged by the young doctor to the benefactors in his life: his cross-grained old uncle, for at least setting in motion the train of events that enabled this education to take place and the money to pay for it; General Miranda, who received a fulsome encomium as the first of the two dedicatees of the work; and Lord Buchan, recognised with a page of gratitude and appreciation for the invaluable support given to Barry during the years at Edinburgh - and with more assistance to come.

The return to London

Dr James Barry's name appears in each of five registers which include the names of dressers and pupils of the United Hospitals of Guy's and St Thomas'. Two119,120 simply index the individual names, two121,122 list, in chronological order, date of entry, signature, duration of the appointment (one year or six months), entrance money paid and the name of the member of the staff with whom the dresser or pupil was entered. On 17 October 1812, Dr James Barry signed the register, the only entrant on the page with MD to his name. The period was for six months, the fee was £20, and he was entered as a pupil to Mr Whitfield123 at St Thomas'. Names of two other members of staff appear on this same page, Mr Henry Cline and Mr John Birch - but not that of Mr Astley Cooper (who was on the Staff of Guy's, not St Thomas'). The final register124 lists the names of pupils who signed up for private courses in Anatomy given by Messrs Astley Cooper and Henry Cline, 1808 - 1814. Barry's signature reveals that he signed up for the Autumn Course 1812/1813, again on the same day, 17 October 1812. This represents the only direct link with Astley Cooper that can be determined in Barry's career.

Meanwhile Mrs Bulkley had also moved back to London - to 301 High Street, Southwark,125 opposite the entrance to St Thomas' and a short walk to the London Bridge,126 most conveniently situated for the new pupil. Apart from the usual teaching in the wards, known as Walking the Wards, a pupil was expected to attend surgical procedures performed by the surgeons on the staff, but not to assist; that was the privilege and duty of the dressers or apprentices. Furthermore there were courses of lectures on Anatomy, Surgery, Midwifery, Medicine and Chemistry to be attended - a useful review of the subjects for the new graduate from Edinburgh.127

That Barry was a dresser to Sir Astley Cooper has often been stated.128,129 Apart from the fact that Cooper at that stage was untitled (his baronetcy was conferred upon him in 1821), this assertion is not borne out by the available original documentation. Nor does it seem likely that Dr Barry could have assisted the great man, for written on a notice 'Regulations for the Theatre' still prominently displayed in the Old Operating Theatre of St Thomas' it is stated that 'Apprentices and the Dressers of the Surgeon who operates are to stand round the Table. The Dressers of the other Surgeons are to occupy the three front Rows. The Surgeon's Pupils are to take their places in the Rows above', and Barry fell into the latter category.

Dr Barry's six-month period as a pupil at the United Hospitals finished in mid-April 1813. His name is next encountered on 2 July in the Register of the Court of Examiners of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, which examination he passed to qualify as a Regimental Assistant - for a fee of two guineas.130-132

Dr Barry joins the army

Why did Dr Barry join the army? Just as intriguing, how did Dr Barry manage to join the army?

At the time of Barry's graduation, after six and a half years of unremitting application, the hoped-for Venezuelan career disappeared forever. However, Barry had successfully sustained the disguise of a young man and had impressive academic achievements and training. If not the Venezuelan army, why not the British army? After all, the Napoleonic wars were raging, and the army needed good surgical recruits. Borodino had been played out, with dreadful losses, on 7 September 1812, just a few short weeks after the final MD examination at Edinburgh.

It seems plausible that Lord Buchan had a hand in these developments, as he was exceptionally well placed to advise and to help the young doctor. With his extensive personal contacts, his imagination, and the particular and on-going interest that he clearly maintained in James Barry, it is suggested that he was responsible for a successful strategy, evolution of the concept and the practical matters required for its execution. The army was actively seeking well-qualified medical staff,135,136 and Dr Barry was recruited into the medical service as a Hospital Assistant on 5 July 1813, three days after his appearance at the Royal College of Surgeons.137 His interview could well have taken place at the old York Hospital in Chelsea rather than at Fort Pitt as has been suggested elsewhere.138 Nothing has emerged to explain how Barry circumvented the routine physical examination, an integral part of the process for every recruit, and here one is obliged to resort to the imagination.

How could the new recruit avoid being discovered to be a woman when stripped? A clever stratagem must have been in place, as the presence of breasts and the absence of male genitalia were anatomical facts impossible to overlook!

Rutherford (who himself had served on examination boards)140 offers the credible explanation that physical examination had been undertaken privately prior to the interview, and that the new recruit had presented letters from an eminent surgeon and a well- known physician to confirm that he was in good health, thereby avoiding the routine army physical examination. Lord Buchan could have arranged such notes, through his influential connections, known to include a number of doctors. Clinicians known to Barry from his recent time at the United Hospitals might also possibly have been prepared to provide confirmation of sound health. An eminent clinician is not necessarily a diligent clinician, and Rutherford has plausibly suggested that the physical examination(s) were more ritual than thorough.144 The solution to this conundrum may lie within the Board Book of Candidates' Examinations, but the location of this remains elusive.145

Barry's first posting was to Chelsea,146 presumably York Hospital, and then the Royal Military Hospital at Stoke in Plymouth.147 Erected privately in 1797, this still survives as a splendid building (Fig. 5).148

Lord Buchan's interest in Barry's progress continued and he kept in touch with another of his medical friends, Dr Skey, of the Hospital in Plymouth. The Earl wrote149 to his Edinburgh friend, Dr Anderson, on 20 November 1813, some months after the young doctor had started working at Stoke: 'Inclosed I send you a letter relating to poor James Barry which came to my hand a few days ago from Dr Skey of the General hospital Plymouth to whom I had recommended him. Dr. Skey's handwriting is almost illegible [!] but I made it out after a good deal of decyphering and find that he has found favour with his Principal whom I intend to thank for his attentions and request the continuance of them.' The Earl was an effective networker nearly two centuries before that term was invented!

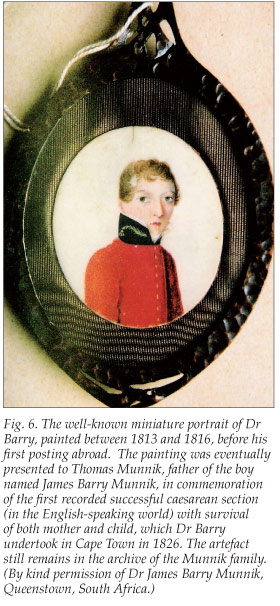

A single artefact remains of Barry's three years and one month at Stoke, the iconic image (Fig. 6) of the young army doctor, wearing a high-collared, plain red, single-breasted coatee with no epaulettes or lacing. This has been accurately dated to the period 1813 - 1816,150 and four possible artists have been suggested.151 Its subsequent story and survival falls beyond the scope of this paper.

This account of the early life and career of Dr James Barry concludes with his appointment as a Hospital Assistant. In December 1815, at Plymouth, he was promoted to the rank of Assistant Staff Surgeon and in August the following year posted to the Cape of Good Hope. The remainder of the more than four decades of his exceptional service is a matter of army record.

I acknowledge with much gratitude the assistance, freely given, of numerous librarians, archivists, colleagues and others, in England, Scotland and Ireland, South Africa and the United States. Institutions include the National Libraries of Scotland, Ireland and South Africa, British Library, National Art Library, Libraries of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Royal College of Physicians of London and of the Universities of Edinburgh, Cape Town and Rhodes (the Cory Library), Benson Library, Wellcome Library and particularly Yale's Lewis Walpole Library, at Farmington, Connecticut. Archivists and their institutions offered willing assistance, including the National Archives at Kew, South African Archives, Cape Town, Archives of Kings College, London, Kensington and Chelsea, Chatham and Rochester in Kent, Archive of the Royal Academy and the Duke of Beaufort's Archive at Badminton. Curators of Museums also afforded invaluable help, notably the Army Medical Services Museum, Aldershot, National Army Museum, Chelsea, Paintings Department at the V & A and the Crawford Art Gallery, Cork.

Colleagues and experts who gave generously of their time and knowledge include Professor Bill Pressly, University of Maryland, Professor John Wass, Oxford, Dr Roger Melvill, Cape Town, Mr John Stevenson, Edinburgh, Dr Ted Myers, Sir Terence English and Dr Emily Kearns, both of Oxford, Mrs Gloria Carnevali, Venezuelan Cultural Attache in London, Dr N M Pettit, Headmaster of the Devonport High School for Boys, Dr James Barry Munnik, Queenstown, South Africa, and Mr and Mrs Dudley Cloete-Hopkins of Alphen, Cape Town.

My wife and family will also be delighted that this prolonged project is now at an end, and I thank them for their patience and support over the past three years.

Notes and References

1. Dunker P. James Miranda Barry. London: Picador, 2000. [ Links ]

2. Kronenfeld A, Kronenfeld I. The Secret Life of Dr. James Miranda Barry. Cambridge, MD: Write Words Inc., 2005. [ Links ]

3. Barry S. Whistling Psyche. London: Faber & Faber, 2004. [ Links ]

4. Holmes R. Scanty Particulars. London: Penguin, 2003. [ Links ]

5. Davies H. Gender Bending Scot to Hit the Big Screen. London: Daily Telegraph, 1 January 2005. [ Links ]

6. Rose J. The Perfect Gentleman. London: Hutchinson, 1977. [ Links ]

7. Brandon S. James Barry (c1797 - 1865). In: Matthew HGC, Harrison B, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004: Vol. 4, pp. 139-141. [ Links ]

8. Rose J (op. cit. ref. 6): p. 17.

9. Holmes R (op. cit. ref. 4): pp. 291- 292.

10. Pressly WL. Portrait of a Cork Family: The Two James Barrys. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 1985; 90: 137-143. [ Links ]

11. Ibid.: p. 145.

12. Holmes R (op. cit. ref. 4): pp. 291-292.

13. Pressly WL (op. cit. ref. 10): p. 145.

14. Barry J. Memorandum of the Service of Dr. James Barry Inspector General of Hospitals 1859: National Archives, W.O. 138/1. [ Links ]

15. McKinnon DR to Graham G, Correspondence 24 August 1865: National Archives, W.O. 138/1. [ Links ]

16. Rose J (op. cit. ref. 6): pp.126-132.

17. Ibid.: pp. 145-147.

18. Laidler PW, Gelfand M. South Africa. Its Medical History 1652 - 1898. Cape Town: Struik, 1971: p. 159. [ Links ]

19. For example, it was stated by Isobel Rae20 that Dr Barry had arrived in Cape Town with a letter of introduction to Lord Charles Somerset, the Governor of the Cape, and this has been repeated by others.21 It would not be at all surprising if this were to be correct, but Rae did not cite any reference for this, and despite a thorough search in the South African Public Library, the Library of the University of Cape Town, the National Archives in Cape Town, the Cory Library in Grahamstown and the Somerset Archives at Badminton, as well as the National Archives at Kew, the document still remains to be located. There is no record of correspondence between Lord Buchan and any member of the Somerset family in the Badminton Archives.22

It was also Isobel Rae who incorrectly stated that Barry was a dresser at St Thomas',23 an oft-repeated statement. In fact, as will be shown later, Barry was registered as a pupil, not a dresser. There was a considerable difference between the two posts.

20. Rae I. The Strange Story of Dr James Barry. London: Longmans, Green, 1958: p. 20. [ Links ]

21. Holmes R (op. cit. ref. 4): p. 59.

22. Milsom EB. Personal communication, 1 August 2005.

23. Rae I (op. cit. ref. 20): pp. 15-17.

24. Pressly WL (op. cit. ref. 10): pp. 127-137.

25. Pressly WL. The Life and Art of James Barry. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1981: p. 1. [ Links ]

26. Somerville-Woodward R. Report on the Barry Family. Unpublished data commissioned by Peter Murray, Esq., Cork 2005. [ Links ]

27. Fryer E. The Works of James Barry, Esq. London: Cadell & Davies, 1809: Vol. I, pp. 1-3. [ Links ]

28. James Barry (1741 - 1806)29 was born in Cork, and from an early age showed an interest in drawing and painting. After tuition from a local artist, he moved to Dublin in 1763, aged twenty-two, never to return to his native city. Edmund Burke admired his work, and for about six years, supported Barry for further study in France and Italy, where the young artist was profoundly influenced both by the style and the content of the great Renaissance painters, particularly Raphael. Following his eventual return to England, Barry prospered for a while, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Academy in 1773, in due course becoming the institution's Professor of Painting. With his difficult personality and limited financial success, perhaps due in part to the subjects he chose to paint, Barry became more and more obtuse, and in 1799 he eventually became the first (and until he was joined in that dubious distinction by Brendan Neiland in 2005, the only) Academician to be expelled. He died in 1806, suffering apoplexy and a massive epistaxis, followed by respiratory complications, quite possibly complications of a pituitary tumour.

29. Pressly WL. James Barry (1741 - 1806). In: Matthew HGC, Harrison B, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004: Vol. 4, pp. 134-139. [ Links ]

30. O'Reilly J. St Finbarr's South Chapel, Cork. Personal communication, 2005

31. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry, 14 April 1804. National Library of Ireland, Dublin. Ref. No. Ms 2069. [ Links ]

32. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry, 14 January 1805. National Library of Ireland, Dublin, Ref. No. Ms 2069.

33. In the letter of 14 January 1805, Mary Ann Bulkley states quite clearly that Margaret, her daughter, is 'but 15 years old'. This means that unless her date of birth was during the first two weeks of January 1790, she had to have been born during the preceding year, 1789. This represents a 50:52 (96.15%) probability.

34. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry (op. cit. ref. 31).

35. John Bulkley to Jeremiah Bulkley undated. Barry Family Albums Vol. ii.

36. Pressly WL (op. cit. ref. 10): p. 147 ref. 43.

37. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry (op. cit. ref. 31).

38. According to figures emanating from the Economic History Services and obtained from the Internet; by extrapolation using retail prices as an indicator, the value of a pound in 1800 was approximately one hundred times its value in 2006. UK House of Commons Research Paper. http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/rp2003/rp03-082.pdf

39. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry (op. cit. ref. 32).

40. Ibid.

41. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry (op. cit. ref. 31).

42. James Barry to Daniel Reardon, 14 December 1809. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii.

43. Eight representative examples of the handwriting of Margaret Bulkley dated between 14 April 1804 and 14 December 1809 were examined by Alison Reboul, a professional document examiner.44 She concluded that all the documents were written by one person, her opinion 'verging on a "definite" level'. However, the final letter of this series was written to Daniel Reardon, the family solicitor, whose invariable practice it was to note on the outside of the cover of all letters received by him, the date of writing and the name of the sender. In this case, he wrote 'Miss Bulkley 14th December 1809' (Fig. 3b), despite the fact that the letter was signed 'James Barry'. More conclusive than that, it cannot be.

44. Reboul A. Personal communication, 5 April 2006.

45. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry (op. cit. ref. 32).

46. Ibid.

47. Barry was repeatedly untruthful about his age, doubtless initially to enhance the appearance of being a youth innocent of facial hair and with a voice not yet broken, when he entered Edinburgh University (where no age restriction existed). In fact, on becoming a medical student James Barry was twenty, and he was twenty-four when he joined the army. At the time of joining the army his year of birth was given as 1799, according to his Statement of Home and Foreign Services,48 yet in the same document in a footnote is written 'But in the Board Book of Candidates Examination in June 1813, he stated his age to be about 18.' However, in the 1859 Memorandum of the Services of Dr James Barry, Inspector General of Hospitals,49 Barry stated that he had '... entered the Army as a Medical Officer under the age of fourteen years ...'. It seems likely that the then sixty-nine-year-old was simply attempting to defer retirement, as by that time his financial resources were rather limited.

48. Statement of Home and Foreign Services. Dr. James Barry: National Archives W.O. 25/3899 f. 614.

49. Dr James Barry (op. cit. ref. 14).

50. Mary Ann Bulkley to Daniel Reardon, 14 December 1809. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii.

51. Dr Edward Fryer52 (1761 - 1826), hailing originally from Frome, Somerset, attended universities at Edinburgh, Leiden (MD 1785) and Göttingen, where he became acquainted with three of the younger sons of George III, and at which stage his interest in his medical career appeared to falter. In 1790 he was back in London and became a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians, and physician to the Duke of Sussex, who, despite his relative impecuniousness, was the owner of a notable library to which Fryer enjoyed access. Much involved in matters of artistic interest in London, Dr Fryer was a close friend of James Barry, RA, and after the death of the artist, collaborating with Lord Buchan, he wrote the definitive Works of James Barry, Esq.53 Fryer's entry in Munk's Roll of the Royal College of Physicians54 records his 'Distinguished ability, various and extensive knowledge, strict probity and unsullied honour, united with the most prompt, ardent and generous feelings, adorned by the most engaging and gentlemanly manners, combined to render him beloved and admired by all who knew him.' Munk's Roll is noticeably silent upon the small matter of Dr Fryer's professional achievements, but it is abundantly clear that he possessed all the attributes to be an ideal tutor for the young Margaret Bulkley.

52. Jefcoate G. Fryer, Edward (1761 - 1826). In: Matthew HGC, Harrison B, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004: Vol. 21, pp. 117-118. [ Links ]

53. Fryer E (op. cit. ref 27).

54. Roll of the Royal College of Physicians (Munk's Roll), Vol. II, p. 412.

55. General Sebastián Francisco Miranda56 (1750 - 1813) was a figure larger than life. Scholar, soldier, traveller, diarist, voluptuary, sometime lover of Catherine the Great of Russia,57 promoter of the rights of women, writer, bibliophile, connoisseur, musician, revolutionary, patriot, diplomat, and twice an escapee from the guillotine, Miranda was also a close friend of James Barry and Dr Fryer. In respect of the education of Margaret Bulkley, two facts stand out. Firstly, he made his splendid and justifiably famous library of some 6 000 books freely available to the young girl for purposes of study,58 and secondly, he offered her a position as a doctor59 in the post-revolutionary Venezuela, the cause that was so dear to his heart.

56. Harvey R. Liberators, Latin America's Struggle for Independence. Woodstock and New York: The Overlook Press, 2000: pp. 19-97. [ Links ]

57. Montefiore SS. Prince of Princes. The Life of Potemkin. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000: pp. 351-383. [ Links ]

58. Margaret Bulkley to Daniel Reardon, 19 May 1806. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii.

59. Earl of Buchan to Dr Anderson, 15 October 1811. National Library of Scotland MS No. 22.4.13, folio 42.

60. James Barry's terminal illness is vividly described by Joseph Bonomi, ARA,61 an architect, and one of Barry's close circle of supportive friends. The artist had been discovered, senseless, in an eating house, by a visiting friend, who eventually found somewhere for him to spend the night. He slept right through that night and the next day, and, after having accepted some tea, fell asleep again. (The reported sleep might well have been impaired consciousness rather than simply sleep.) During this second night, he suffered a massive epistaxis. Attended by Dr Fryer, he subsequently developed pain in his side together with a temperature, and chest symptoms, eventually going downhill and dying on the sixteenth day after the onset of the illness.62 This could have been the result of inhalation pneumonia.

Pressly drew attention to the possibility that Barry had developed features of acromegaly over the years.63 This view was recently strongly supported by Professor John Wass, Professor of Endocrinology at Oxford.64 It is possible that Barry had a large pituitary adenoma which had eroded into the sphenoid sinus with associated pituitary apoplexy and haemorrhage. A simple X-ray of the mortal remains, which lie in the crypt of St Paul's, could settle this intriguing possibility. Permission for access to the mortal remains by this author has been declined.

61. Joseph Bonomi to Lord Buchan, 14 February 1806. Jupp Annotated Royal Academy Catalogues Vol 4, pp. 123-124.

62. Newby E. The Diary of Joseph Farington. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998: Vol. vii, pp. 2684- 2622, 26 February 1806 and p. 2694, 16 - 17 March 1806. [ Links ]

63. Pressly WL (op. cit. ref. 10): p. 132.

64. Wass JAH. Personal communication, 2006.

65. Pressly WL (op. cit. ref. 10): p. 134.

66. Ibid.: p. 138.

67. Newby E (op. cit. ref. 62 ): Vol. viii, p. 2889.

68. Daniel Reardon to Mrs Bulkley, 30 March 1810. Draft of letter. Barry Family Albums, Vol ii.

69. Margaret Bulkley to Daniel Reardon, 19 May 1806 (op. cit. ref. 58).

70. James Barry to General Miranda, 7 January 1810. Archivo del General Miranda, Tomo XVIII, f 23, Academia Nacional de la Historia, Caracas.

71. Jeremiah Bulkley to Margaret Bulkley, 27 November 1809. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii. In this letter Jeremiah, wrote to his daughter, 'Old Tobin told his son David he had seen your mother in London that she appeared shabby and seemingly much distressed. He sd Tobin said you got your livelyhood [sic] by teaching in a Family - He is and ever was remarkable for dealing in Lies, I do not believe a word of what he said.' On this occasion, old Tobin appeared to have been telling the truth.

72. This letter, and three others from Jeremiah which followed, dated 24 February 1810, 1 March 1810 and 9 April 1810, all ended up in Daniel Reardon's office, although it would appear that a letter to Margaret enclosed in the February cover was forwarded, as it is not among the papers available. It seems that Margaret and her mother were simply no longer communicating with the distraught man, and there is no evidence to suggest that either of them ever did so again. Margaret, especially, had no place for her father in the new life that she was so carefully constructing for herself.

73. General Miranda's library with its 6 000 volumes, valued after his death at £9 000, was justly famous.74 Some twelve years after his death, the first of two auctions of the books was held, but the catalogues75 only listed about 4 000 volumes, which suggests that the more covetable volumes could have been disposed of before the remainder came under the hammer.

74. Harvey R (op. cit. ref. 56): p. 96.

75. Miranda F de, Grases Gonzáles P, Uslar Pietri A. Los Libros de Miranda including Catalogues of the Library and of the Sales of 1828 and 1833. Caracas: Comit, de Obras Culturales, 1966.

76. The precise nature of a Liberal Education77 is difficult to define, but it included a wide range of studies of which a gentleman would be expected to have some knowledge at least. Scholarship in itself was not the goal so much as absorbing concepts and appreciation of ideas such as behaviour, style, taste and manners, but at the same time providing a strong foundation from which scholarship, if required later, could proceed. General enlargement of the mind and expansion of the intellect was the aim, with such subjects as the Classics, Latin and Greek in considerable depth, Mathematics, Experimental and Natural Philosophy (physics), as well as History, Geography, and the Arts and, of course English poetry and literature, probably with a foreign language included for good measure.

77. Rosner L. Medical Education in the Age of Improvement. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991: pp. 35-38.

78. Barrell J. The Birth of Pandora and the Division of Knowledge. Basingstoke and London: Macmillan, 1992: p. 165.

79. Lord Buchan to Dr Robert Anderson, 15 October 1811. National Library of Scotland. adv. MS. 22.4.13 f. 42.

80. Mary Ann Bulkley to James Barry, 14 January 1805 (op. cit. ref. 29).

81. Rosner L (op. cit. ref. 77): p. 11.

82. Harvey R (op. cit. ref. 56): p. 90.

83. Ibid.: p. 96.

84. Mary Ann Bulkley to Daniel Reardon, 14 December 1809. Barry Family Albums, Vol ii.

85. Leith and London Smack Directory. Leith: London and Leith Old Shipping Company. Precise date unk.

86. The vessels, exceptionally seaworthy cutter-rigged smacks, were a development of the Berwick salmon boats. They were of approximately 100 to 120 tons gross, and were 'most elegantly fitted up for the accommodation of passengers' with separate entrances to the two communal cabins, one for men and the other for women. The berths situated around the cabin offered a certain amount of privacy. Some smacks even carried a piano forte. The fare was three guineas each, a not inconsiderable sum of money.

87. Daniel Reardon & Co. Statement of Account Mrs. and Miss Bulkley. 3rd April 1810. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii.

88. In the same statement is an item recording the payment of £2.15.~ to a Mr White, Music Master. It is most likely that this was for Mrs Bulkley, as nowhere in the extensive writings about Dr Barry is there any reference to a fondness for music. Later, there was correspondence with Daniel Reardon about a new case for Mrs Bulkley's pianoforte, which was made by a Mr Kirkman of Broad Street, and also subsequently sent by sea to Edinburgh, together with a piano stool.

89. Mrs Bulkley received the disbursement of £10 from the hands of Daniel Reardon's brother, Michael, on 28 November 1809. That was a Tuesday, and the next sailing for Leith was two days later, on 30 November. It is reasonable to assume that the pair would have left then, as it was already becoming somewhat late for matriculation at the University. This particular voyage took five days, generally eight knots being achieved. One passage is recorded as having taken only forty-two hours, which was very fast indeed. As we know from Mrs Bulkley:90...'After a voyage of 5 days we arrived safe at Leith and as soon as possible took lodging in Edinburgh, where I find everything (almost) cheaper than in London.' They therefore arrived in Scotland on about Tuesday 5 December, barely in time for the commencement of the Winter Term.91

90. Mrs Bulkley to Daniel Reardon (op. cit. ref. 84).

91. Rosner L (op. cit. ref. 77): p. 25.

92. James Barry to Daniel Reardon (op. cit. ref. 42 ). There is also mention in this, the first recorded letter bearing the signature 'James Barry', that introduction to the Earl of Buchan had taken place. So, Margaret Bulkley had never met Lord Buchan while in London, and it would also appear that his Lordship was not party to the conspiracy to conceal Barry's sex. In support of this contention is the fact that in none of the (admittedly scanty) correspondence from the Earl did he refer to Barry in any but the masculine gender or give any indication that he suspected otherwise, despite such apparent youth. Writing to his friend, Dr Anderson, in 1810,93 Lord Buchan had described the student as 'poor Barry', and went on to tell of '... the friendship which subsisted between Barry's Uncle & myself & other circumstances ...'. Whether the use of the word 'poor' inferred that the student was rather small with an apparently frail physique, apparently still appearing to be prepubescent, or whether it referred to a lack of funds, is difficult to say, but Lord Buchan could have meant either.

Furthermore, tellingly, in a letter from Barry to General Miranda94 written about a month after his arrival in Edinburgh, the postscript (complete with an asterisk for emphasis) states: 'As Lord B - nor anyone else here knows anything [about] Mrs Bulkley's daughter, I trust my dear General that neither you nor the Doctor will mention in any of your correspondence any thing about my cousin's friendship &Ca for me ...'. It would therefore appear, on the evidence available, that the Earl had not been made privy to the sex of the new James Barry. And yet ...' the proceeds of the sale of the Works of James Barry, Esq. by Dr Fryer, and with the full co-operation and support of Lord Buchan, were to go towards the 'advantage of certain indigent relations of the departed Artist ...'.95

93. Lord Buchan to Dr Anderson, 5 July 1810. National Library of Scotland Adv. MS. 22.4.13 No. 38.

94. James Barry to General Miranda (op. cit. ref. 70).

95. Pressly WL (op. cit. ref. 10): p.139.

96. James Barry to Daniel Reardon (op. cit. ref. 42).

97. Mary Ann Bulkley to Daniel Reardon (op. cit. ref. 84).

98. Mary Ann Bulkley to Daniel Reardon, 11 May 1810. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii.

99. James Barry to General Miranda (op. cit. ref. 70).

100. Jeremiah Bulkley to Margaret Bulkley, 27 November 1809 (op. cit. ref. 71).

101. James Barry to Daniel Reardon (op. cit. ref. 42).

102. Matriculation Record, Edinburgh University: EUL Da 34.

103. Rae I (op. cit. ref. 20): p. 11.

104. Rosner L. Ibid.: p. 62.

105. List of the Graduates in Medicine in the University of Edinburgh, from MDCCV to MDCCCLXVI. Edinburgh: Neill & Company, 1867. E.U.L. Ref. No. S.R.Ref. .378(41445) Uni.

106. Rosner L (op. cit. ref. 77): pp. 72-85.

107. Russell MP. James Barry - (1792 (?) - 1865) Inspector General of Army Hospitals. Edinburgh Medical Journal 1943; 50: 558-567.

108. Rosner L (op. cit. ref. 77): p. 73.

109. Ibid: p. 77.

110. Lord Buchan to Dr Anderson, 15 October 1811. National Library of Scotland Adv. MS. 22.4.13 f. 42.

111. The Eleventh Earl of Buchan was yet another of the remarkable men who played an indispensable role in the early career of Dr James Barry. The Buchans are descendants of Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland, and the first Earl, Alexander (1343 - 1405) was the son of Robert II, brother of Robert III and uncle of James I. The second Earl fighting with the French in 1423, defeated the English at Beaugé, and was made Constable of France. David Steuart Erskine (1742 - 1829),112 the Eleventh Earl, was considered by some to be mildly eccentric. He maintained an extensive correspondence with many notable persons of his time, including the King, George III, whom he referred to as his cousin. He is remembered as the founder of the Scottish Society of Antiquaries, but his close friendship with many of the staff at Edinburgh University certainly smoothed the way for James Barry as a medical student. Nor did his support dwindle after Barry qualified. His hand can be sensed in the direction Barry's career took after obtaining the MD; he continued to support the young doctor during the time at Plymouth, and possibly later, even when Dr Barry was appointed to the Cape, although proof of the latter remains to be identified.

112. MacLeod EV. David Steuart Erskine (1742 - 1829). In: Matthew HCC, Harrison B, eds. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004: Vol. 18, pp. 524-526.

113. Barry J. Disputatio Medica Inauguralis de Merocoele vel Hernia Crurali. Edinburgh: C Stewart, 1812. Ref. EUL Att. 83.7.16/2.

James Barry's work survives in its original state, his chosen subject being Femoral Hernia. That condition had recently been written up by Alexander Monro Tertius, the Professor of Anatomy and Surgery (De Morbida Aesophagi Intestinorumque Structura), as well as by Astley Cooper114 in his famous two-volume monograph (enormous both in concept and sheer physical size, and dedicated to Alexander Monro, Barry's Professor), so the subject could be considered to be topical. The thesis has been carefully studied (in translation)115,116 and it represents a very fair view of the ideas held about the subject two centuries ago, when femoral hernia, being relatively uncommon, was not particularly well diagnosed or managed. Barry's work is particularly strong in respect of anatomical detail, and it certainly merited acceptance by the examiners.

114. Cooper A. The Anatomy and Surgical Treatment of Crural and Umbilical Hernia. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees & Co & E Cox, 1807: pp. 12-34: plates 1-8.

115. Kearns E. Personal communication, 2003.

116. Coulton N. Unpub. translation of thesis, 2002.

117. Rae I (op. cit. ref. 20): p. 3.

118. Russell MP (op. cit. ref. 107): p. 560.

119. Alphabetical Index of Pupils and Dressers, St. Thomas' 1723 - 1819, Guy's 1768 - 1819. King's College Archives. TH/FP1/IN 1723 - 1819 f 46. Dr Barry is entered as 'PT', abbreviation for Pupil at St Thomas'.

120. Register of Pupils 10 April 1799 - November 1833. St. Thomas' and Guy's. King's College Archives TH/FP4/2 f 33.

121. Pupils and Dressers Cash Book 1811- 1837. King's College Archives TH/FP7/1 f 5.

122. Surgeons' Pupils of Guy's and St. Thomas' Feb 1812 - Feb 1827. King's College Archives TH FP7/1 G/FP4/1 f.8.

123. Mclnnes EM. St. Thomas' Hospital. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1963: p. 91.

Mr. Whitfield was the Hospital Apothecary: he was one of a dynasty of Whitfields who held that office. His function corresponded to that of a Senior Resident Medical Officer, doing two ward rounds daily, one in the morning and the other at night. He attended mainly to Medical patients, but also to Surgical patients requiring medical attention. Many Pupils were entered under his name.

124. Register of Anatomy Pupils of Mr. Astley Cooper and Mr. Henry Cline 1808 - 1814. King's College Archives. TH/FP1/1 1808 - 1814 f 33. Barry's signature present.

125. Dr Fryer to Mrs Bulkley, 31 October 1812. Barry Family Albums, Vol. ii.

126. Laxton P, Wisdom J. The A to Z of Regency London. London: London Topographical Society No 131, 1985: p. 25.

127. Guy's Hospital Medical School Records (2006). http://www.aim25.ac.uk/cgi-bin/search2?coll_id=5548&inst_id=6

128. Rose J (op. cit. ref. 8): p. 27.

129. Holmes R (op. cit. ref. 4): p. 41.

130. Register of the Court of Examiners of the Royal College of Surgeons of England f. 93.

131. The Register of the Court of Examiners provides a fascinating glimpse into some of the functions of the College. The Court of Examiners sat formally to undertake their duties, which included examinations of disabled men from the Services to determine compensation claims. That was in addition to the Candidates for Professional Examinations. On 2 July 1813, the date of Dr Barry's examination, the Court included Sir Everard Home, Bart., Sir William Blizard, Sir James Earle and Henry Cline among the ten surgeons present. For the fee of two guineas, Dr Barry was found to be suitably qualified for the post of Regimental Assistant. In respect of these examinations, this is an appropriate place to lay another persistent Barry misconception to rest. Rae mistakenly reported132 that Barry's examination by the Court of Examiners had taken place on 15 January 1813, a statement uncritically repeated by Holmes.133 It is true that a Mr Barry was examined on that date, but he was Samuel Barry, who entered the Army Medical Service on 18 January 1813 as a Hospital Mate. He obtained the MD Glasgow in 1822, and died in 1837.134

132. Rae I (op. cit. ref. 20): p. 17.

133. Holmes R (op. cit. ref. 4): p. 53.

134. Johnstone W. Roll of Commissioned Officers in the Medical Service of the British Army 20th June 1727 - 23rd June 1898. Aberdeen, 1917. No. 3550. Samuel Barry. Hospital Mate 18th January 1813. Died at Portsmouth 18th October 1837.

135. Russell MP (op. cit. ref. 107): pp. 559-560.

136. Rosner, L (op. cit ref. 77): pp. 20-21.

137. Statement of the Home and Foreign Services (op. cit. ref. 48).

138. It is difficult to establish just where Barry was interviewed at the time of recruitment. It is maintained by Rose139 and Rutherford140 that Fort Pitt at Chatham was the venue. Certainly, Fort Pitt was for many years used for that purpose, and it also became an important Military Hospital and Medical School. But that was after the time of Barry's recruitment. According to a history of the site,141 the Garrison manning the Fort was transferred following the first defeat and capture of Napoleon in January 1814. In the September, wounded soldiers were housed in the Fort on a temporary basis, but eventually, the place became a Military Hospital in 1824. Barry's interview took place on 5 July 1813, and at that time, Fort Pitt was still an active garrison. The main military hospital then was the York Hospital in Chelsea142 which was recorded as existing as late as 1829.143

139. Rose J (op. cit. ref. 6): p. 29.

140. Rutherford NJC. Dr. James Barry: Inspector General of the Army Medical Department. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 1939; 73: 110.

141. Cooper J. Fort Pitt: Some Notes on the History of a Napoleonic Fort, Military Hospital and Technical School. Rochester: Private Typescript publication, 1974: p. 10.

142. Denny B. Chelsea Past. London: Historical Publications Limited, 2001: p. 83.

143. Faulkner T. Historical and Topographical Description of Chelsea and its Environs: etc. London: Nicols & Son, 1829: Vol. II, p. 24.

144. Rutherford NJC (op. cit. ref. 140): pp. 110 -114.

145. This item is mentioned in a footnote on the Statement of the Home and Foreign Services (W.O. 25/3899 f. 614). Above the Date of Birth 'about 1799' is the note 'If this be correct he must have entered the Service when he was 14 years of age *' and next to the asterisk at the bottom of the page 'But in the Board Book of Candidates' Examinations in June [sic] 1813 he stated his age to have been 18.' So far it has not been possible to locate this Board Book, but if found, it could well contain very interesting information ...

146. In the Medical Officers' Service Records (Archives of the Army Medical Services Museum Vol. 2 f 157) are entered the rank and pay rates of Dr James Barry. In this document the first recorded Station is given as Stoke, the large Royal Military Hospital at Stoke Damerel, Plymouth. However, Chelsea (presumably the York Military Hospital), preceding Plymouth, is mentioned, on the second page of the Return of Services and Professional Education.158 In the Statement of the Home and Foreign Services (W.O.25/3899) at the commencement of Barry's military career, as a Hospital Assistant, is written 'After the first three months on Half Pay'. It is feasible, then, that Barry served such an introductory period at York Hospital, although nowhere is this spelled out as such.

147. National Archives WO 3910 f 3. Return of the Services and Professional Education: Dr. James Barry, 7 April 1824.

148. This impressive building survives virtually intact, including the operating theatre with its original terrazzo floor, the drainage gutters of which, however, have been filled in. It is currently put to excellent use as the Devonport High School for Boys, a Grammar and Specialist Engineering School.

149. Lord Buchan to Dr Anderson, 20 November 1813. Scottish National Library Adv. MS 22.4.13. f 62.

150. Brewer G (National Army Museum, Chelsea). Personal communication, 2006.

151. Coombs K (Victoria and Albert Museum). Personal communication, 2006. The four artists who could conceivably have painted the portrait miniature are:

Condy (?) NM, b. Plymouth 1799, was initially a painter of miniatures, quite possibly as a teenager.

Dennis GA, miniature painter, at 9 Dock Street, Plymouth. c. 1800. An example, similarly marked was executed in 1816.

Hamlyn A. A Jane Hamlyn exhibited at the Royal Academy from a Plymouth address in 1819. Augusta is known to have painted miniatures.

M Taylor, a travelling miniaturist advertised as working in Exeter and Plymouth in 1798.

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

H M du Preez

(michael.dupreez@gmail.com)