Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.39 suppl.2 Pretoria Dec. 2019

https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns2a1722

Smiljana Dukicin Vuckovic; Andelija Ivkov-Dzigurski; Ljubica Ivanovic Bibic; Jelena Milankovic; Jovanov; Ivan Stojsic

Department of Geography, Tourism and Hotel Management, Faculty of Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia ljubica.ivanovic@dgt.uns.ac.rs

ABSTRACT

This study was conducted to determine the attitudes of teachers concerning inclusion in schools all over Serbia. The respondents were teachers of different subjects who were tasked to anonymously complete the provided closed-type questionnaire (970 respondents). Primary and secondary school teachers from urban and rural areas of the Republic of Serbia participated in the research. The results indicate that the teachers are supportive of inclusion. Despite significant differences in respondents' answers, the results of the research show that there are many similarities in teacher responses toward inclusive education. The results show that it is still necessary to work on the implementation of inclusive education in Serbia, especially to educate the teaching staff and involve experts in the planning and development of individual educational plans.

Keywords: attitudes; inclusive education; Serbia; teachers

Introduction

During the first half of the 20th century disability was often ignored. People with disabilities were usually looked after by their families or they lived in institutions. In addition, Eiesland (1994) points out that, as a result of the baby boom and a decrease in infant mortality rates, there was an increase in the number of children born with disabilities, giving rise to philanthropic and parent advocacy groups. As a response to these advocacy demands, the development of professional educational, social, and medical services emerged (Eiesland, 1994). Due to the increased number of children with special needs and with disabilities, there was a need for better education and training of these children. Inclusive education is one of the solutions for including these children in the educational process.

Theories of inclusion and inclusive education have a valuable influence on special education policies and practices in both developed and developing countries (Artiles, Kozleski & Waitoller, 2011; Singal & Muthukrishna, 2014). Although inclusion is a part of the human rights movement, working with students with disabilities in formal educational settings is largely dependent on the attitudes of teachers (Avramidis, A, Bayliss & Burden, 2000; Berry, 2010; Haq & Mundia, 2012; Hill & Davis, 1999; Huang & Diamond, 2009; Odom, Vitztum, Wolery, Lieber, Sandall, Hanson, Beckman, Schwartz & Horn, 2004).

Teachers believe that general education is not the most appropriate environment to meet the academic and social needs of students with disabilities (Heflin & Bullock, 1999). They also find that inclusive educational settings are more suitable and effective for students with mild disabilities compared to students with severe disabilities (Langdon & Vesper, 2000).

Studies on the attitudes of teachers toward inclusion have demonstrated differences in attitudes influenced by factors such as gender (Alghazo & Gaad, 2004), teachers' personal beliefs (Dupoux, Hammond, Ingalls & Wolman, 2006), the severity of the student's disability (Langdon & Vesper, 2000; Scruggs & Mastropieri, 1996), and teacher training and instructional skills (Minke, Bear, Deemer & Griffin, 1996; Shoho, Katims & Wilks, 1997; Vaughn, Schumm, Jallad, Slusher & Saumell, 1996; York & Vandercook, 1990). According to Tsokova and Becirevic (2009) inclusive education in Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina has not received sufficient popularity and support in society. In both countries, public opinion towards inclusive education was examined and it was concluded that negative attitudes still prevail. In Croatia, teachers are considered competent to teach children with disabilities. They have good cooperation with professional staff in schools (special teachers, speech therapists, social pedagogues), whose task is to support all participants in inclusive education (Ralic, Krampac-Grljusi & Lisak, 2012). Although Croatia has made significant improvements in the field of inclusive education, the medical approach remains (deficit and a lack of awareness of the need to adapt the environment to make it accessible to children with disabilities).

The purpose of this research was to highlight the problem of inclusive education in Serbia and to share experiences with other countries. The results can generate new ideas creatively and realise important goals. Also, these studies highlight the significance of the experience of direct participants in inclusion in education. Teachers who grapple with inclusive education in their daily practice give valuable data for such research. Teachers and their experiences are good indicators of how inclusive education should be designed.

Theoretical Framework

This study is about inclusion in education. Inclusion is a term which expresses commitment to educate each child, to the maximum extent appropriate, in the school and classroom he or she would otherwise attend. Theory-based attitudes support inclusion in education as an issue recognising the rights of students with disabilities. These rights include equal access and equal opportunities in education (Ainscow & César, 2006; Avramidis, E & Norwich, 2002; Booth, 2000).

This research included teachers' experiences about inclusive education in schools in Serbia, based on the assertion that knowledge comes only or primarily from sensory experience (Psillos & Curd, 2010). This research was designed to measure and to evaluate the attitudes of teachers who meet with children with special needs and with disabilities in their everyday practice. The results from practice are important for this kind of research.

Most inclusion studies don't have an adequate theoretical background. A lack of empirical testing also exists (Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Hol-combe Ehrhart & Singh 2011). According to Mor Barak (1999:52) "employee perception of inclusion-exclusion is conceptualized as a continuum of the degree to which individuals feel a part of critical organizational processes. These processes include access to information and resources, connectedness to supervisor and co-workers, and ability to participate in and influence the decision-making process."

Inclusive education in Serbia

The year 2001 (general education reform) was marked as the starting point for the implementation of the reforms within the educational system in Serbia (Cvjeticanin, Segedinac & Segedinac, 2011) in accordance with the general development of the system of education of the European Union. The Government of the Republic of Serbia issued two documents related to inclusive education: Law on the Fundamentals of the Education System (Republic of Serbia, 2009) and Strategy of the Development of Education in Serbia until 2020 (Mitrovic, 2012; Republic of Serbia, 2009, 2010). In Serbia, inclusive education is legally founded by the Law on the Fundamentals of the Education System 72/2009 (Republic of Serbia, 2009). This law abolished the enrolment policy that discriminated and prevented equal education for all; it stipulated that from the 2010/2011 school year all children would be included in the regular education system.

The medical model, which is still dominant in schools in Serbia, is in stark contrast to the social model that is widely accepted in Europe. All children have the right to a quality education, as guaranteed by law. However, in Serbia, 85% of children with special needs do not attend any school (Radivojevic, Jerotijevic, Stojic, Cirovic, Radovanovic-Tosic, Kocevska & Paripovic, 2007), while a number of schools in Serbia have alarmingly high numbers of Romani students, reaching up to 73% in 2012/13 (European Roma Right Centre, 2014). Children with special needs quite often become targets of discrimination. This is a common problem since the school climate does not promote democratic values. Additionally, teachers still need to develop a more positive attitude and competences necessary for working with children with different needs (Dedej, 2011; Radivojevic et al., 2007).

According to the Law on the Fundamentals of the Education System (Republic of Serbia, 2009), children who, for any reasons, require additional support in education, have the right to attend school in accordance with the individual educational plan (IEP) based on their pedagogical profiles (Pavlovic Babic, Simic & Friedman, 2018). Even though the IEP was introduced as a supportive tool, teachers still face many difficulties in including children with special needs in regular classes. Large class sizes in urban schools are one of the notable challenges and teachers lack adequate expertise to carry out inclusive practices because they have not received adequate teacher training (Malinen, Savo-lainen & Xu 2012; Yada & Savolainen, 2017).

Our inclusion framework provides a launching point for expanding the diversity literature by developing new ideas pertaining to the experiences of teachers in schools in Serbia.

Methodology

The aim of the research was to involve as many teachers as possible from different urban and rural regions in Serbia to determine what their opinions on implementing inclusive education were. The purpose of the research was to show whether teachers agreed on key questions regarding inclusion and how much their views on inclusion were similar or different. Also, one of the aims was to include as many teachers of different subjects as possible to determine the differences in their answers.

It was assumed that the teachers of different gender and places of employment would have gained different experiences related to inclusion and would, therefore, have developed different attitudes toward inclusive education. The starting hypothesis was that teachers agreed about the importance of inclusive education and that it was necessary to carefully plan inclusive education and its goals. The hypothesis included in the research stated that there are statistically significant differences in the respondents' attitudes. The process of implementing inclusive education differs significantly - depending on the subject. One of the hypotheses was that statistically significant differences existed in the opinions of teachers who taught different subjects and had more teaching experience that others.

This research on the attitudes of teachers towards inclusive education is one of the first done on the subject in Serbia.

Data Collection

The field-survey research method was used in this study. The design of the questionnaire was based on the original study.

The research was conducted during the 2014/2015 and 2015/2016 school years. The sample was random. The survey resulted in 970 correctly completed questionnaires. The respondents were of different gender, had varied experience, were not employed at the same schools nor lived in the same places, and taught different subjects. The research was conducted in urban and rural environments throughout the Republic of Serbia and participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

The schools' principals or teachers were asked to introduce and deliver the questionnaire to the teachers.

Participants' Characteristics

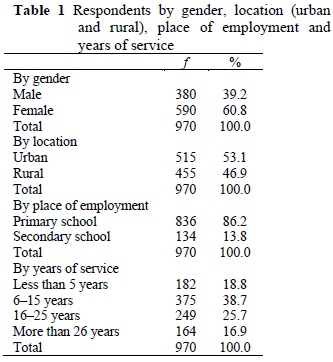

The final number of correctly completed questionnaires was 970. The respondents were mainly teachers who had taught between six and fifteen (38.7%), and between sixteen and twenty-five years (25.7%) (see Table 1).

Only 18.8% of respondents had taught less than five years, while only 16.9% of respondents had taught more than twenty-six years. Most of the respondents worked in primary schools (86.2%), while only 13.8% worked in secondary schools. The reason for the big difference was that there are more primary schools and primary school teachers than secondary schools and secondary school teachers in Serbia. The results from the work environment are as follows: 53.1% of teachers taught in urban schools, while 46.9% worked in rural schools. The majority of the respondents were women (60.8%), while only 39.2% were men. This was expected as, in general, more teachers in the country are female. In addition, teachers of 32 different subjects (from primary schools, high schools and secondary technical schools) took part in the research. The respondents who participated taught Geography (11.5%), Serbian (language) (10%), Mathematics (9.3%), and History (8.4%).

Only 7.7% of the respondents taught Biology and lower grades in elementary school. As Serbian and Mathematics are the subjects with the highest number of weekly classes, more teachers of these two subjects participated, thus, the results were expected. As many teachers are employed in primary schools, a great number of teachers of lower grades in elementary schools participated. The number of teacher participants of other subjects was much lower, and included teachers of Chemistry, Physics, Information Technology (IT), foreign languages, Sociology, Philosophy, Logic, Constitution and Citizen's Rights, Economics, Law, Statistics, Accountancy, Religion, Citizen's Rights, Art, Music, Technical Education, Physical Education (PE). Participants also included school psychologists and pedagogues. All of the subjects are regarded as equally important in the planning and implementation of IEP in inclusive education.

Research Instruments

A three-part questionnaire with 15 items was used in data collection. The research was conducted through personal surveys and every respondent received a questionnaire. The first part (5 items) of the questionnaire collected demographical data. The second part (5 items) contained yes/no questions. The third part (8 items) was a 5-item Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) that measured attitudes toward inclusive education. The reliability of the third part (8 items) was analysed using Cronbach' s alpha, of which the obtained value was 0.72. Taking into account that reliability coefficients higher than 0.7 are considered satisfactory, the questionnaire has an acceptable level of reliability. The content of the questionnaire is original; it is not based on any available research of this type. The questionnaire was created to follow the trends regarding inclusive education in Serbia.

Data Analysis

The obtained data was analysed using version 23 of the SPSS statistical program, which has been widely applied in similar researches (Alghazo & Gaad, 2004; Altinkök, 2017; Sharma, U, Moore & Sonawane, 2009). The most common statistical analyses that have been applied in this research include: an initial descriptive statistical analysis followed by the /-test analysis for independent samples, and the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In order to determine how significant the difference was among individual groups, the post-hoc Scheffe test was used as one of the most rigorous and most commonly applied tests. The t-test of independent samples was applied in order to compare the arithmetic means of two groups of respondents: male and female, teachers working at primary and secondary schools, teachers working at the urban and rural schools. The one-way analysis of variance, ANOVA, was used to examine the effect of participants' social characteristics (independent variables) on their responses to items related to the attitudes toward inclusive education (dependent variables).

Results

The t-test of independent samples was applied to compare the arithmetic means of two population groups (see Table 2). Only the results showing statistical relevance at the level of significance p < 0.05 are presented in this paper.

The respondents mostly agreed with the given statements or they were indifferent towards certain statements. The following statement scored the highest mark among primary school teachers: Inclusion should be planned in detail in cooperation with a great number of experts. The respondents mostly disagreed on the statement: The inclusion of children with special needs is a good decision for education in Serbia. The statistically significant difference in the answers of the primary and secondary school teachers is noticeable in four out of ten tested statements.

As indicated in Table 3, the respondents either agreed with the given statements or they were indifferent towards certain statements. The following statement scored the highest mark among urban and rural teachers: Inclusion should be planned in detail in cooperation with a great number of experts. The respondents mostly disagreed with the statement: The inclusion of children with special needs is a good decision for education in Serbia.

Disagreement with this statement can be explained by the fact that most teachers are not sufficiently prepared for inclusive education. In Serbia, future teaching staff are still not trained sufficiently for the inclusion of and working with children with special needs in regular schools. The statistically significant difference is noticeable in eight out of ten statements.

The results in Table 4 show that the respondents agreed with the given statements or that they were indifferent towards certain statements. The statement the respondents mostly agreed with is:

Inclusion should be planned in detail in cooperation with a great number of experts. The statistically significant difference is noticeable in four out of ten tested statements.

Table 5 presents the results showing the statistical relevance at the level of significance p < 0.05.

The results in Table 5 show that the respondents agreed with the given statements or that they were indifferent towards certain statements. The statement the respondents mostly disagreed with is:

Inclusion influences other children in the class in a bad way.

The analysis of the variance, ANOVA, was implemented in order to determine the statistically significant differences between answers given by the respondents who taught different subjects. The statistically significant difference for these groups of respondents was determined only according to one statement.

Discussion

The results of the t-test show that the respondents employed in primary and secondary schools have not developed equal attitudes toward inclusive education. The statistically significant difference noticeable in four out of ten tested statements partially confirms the following hypothesis: statistically significant differences exist between answers given by primary school teachers and those given by secondary school teachers. This hypothesis is justified owing to the fact that primary and secondary school teachers face different kinds of challenges related to inclusive education and students with special needs. There are more students with special needs in primary schools than in secondary schools. Therefore, the attitudes of primary school teachers could be perceived as more objective and reliable. The results of research in other countries on the topic of different attitudes of certain groups of teachers and students who study to be teachers correlate with the results of this research to a high extent (Cardona, 2009; Dupoux et al., 2006; Ernst & Rogers, 2009; Sharma, A & Dunay, 2018; Tsokova & Becirevic, 2009). In general teachers are of the opinion that it is necessary to include as many experts as possible in the processes of inclusive education (see Figure 1). Furthermore, it is common knowledge that this is an extremely complex area and that teachers are not trained sufficiently for the implementation of inclusion in Serbia (Milankovic, Ivkov-Dzigurski, Dukicin, Ivanovic-Bibic, Lukic & Kalkan, 2015). According to RadiC-Sestic, Radovanovic, Milankovic-Dobrota, Slavkovic and LangoviC-MilicviC (2013), the team approach of general and special education teachers proved to be useful for all students in an inclusive school, which should provide all prerequisites for their joint work. The results of the t-test show that the respondents employed in urban and rural regions do not have equal attitudes toward the implementation of inclusion in education. The noticeable statistically significant difference in eight out of ten tested statements confirms the following hypothesis: the differences in the answers of respondents employed in urban and rural environments are statistically significant. The following hypothesis is, thus, justified: the teachers who work in different environments face different kinds of challenges related to inclusion of children with special needs. Since urban regions are bigger, there are more students with special needs. On the other hand, urban regions offer more opportunities to children with special needs and inclusion is more easily implemented. A great number of rural schools in Serbia lack basic teaching means and it is almost impossible to work with children with special needs in those schools (see Figure 2) (Lescesen, Ivanovic-Bibic, Dragin & Balent, 2013). Other authors confirm the above-mentioned state of inclusive education (Fakolade, Adeniyi & Tella, 2009; Ryan, 2014).

The statistically significant difference among male and female respondents is noticeable in four out of ten tested statements. Therefore, the following hypothesis is only partially confirmed: there are significant differences in the attitudes of teachers of different gender. It is very important to take into consideration the fact that there are more female than male teachers, which means that women are faced with challenges related to inclusion much more often. The statement: Including pedagogical assistants in inclusive classes is an important step in helping the school employees, was marked as highly significant by the female respondents. This is, after all, one of the guidelines on which inclusive education should be based (Gal, Schreur & Engel-Yeger, 2010; Haq & Mundia, 2012).

The analysis of variance, ANOVA, partially confirmed that there are statistically significant differences in the attitudes of the respondents with more experience. Ten statements were tested, while the statistically significant difference was noticeable in three out of ten. For this reason, the hypothesis is only partially confirmed. In this part of the research it was more important to collect data showing that teachers with different periods of work experience agreed about the key problems of inclusive education. Since they mostly agreed with the given statements, it can be concluded that all the teachers realised what kinds of problems Serbia faced in implementing better inclusion. It can also be concluded that schools all over Serbia faced similar challenges in their attempts to implement inclusion.

The hypothesis that was a statistically significant difference existed in the answers of the teachers of different subjects was not confirmed. Inclusion of children with special needs is quite specific when it comes to different subjects, while the results of the questionnaire used in this research only revealed respondents' general attitudes.

Inclusive education in Serbia is still under development and there is a lack of scientific literature dealing with this topic. Teacher experiences and their views on inclusion in schools are very important for further planning of inclusive education in Serbia. According to Odom, Buysse and Soukakou (2011) issues that may affect the provision of inclusion in the future are related to implementation science, changing child and family demographics, the current economy, retrenchment, and the cost of inclusion.

Conclusion

Joining forces, knowledge, and experience of experts in different fields can lead to successful implementation of inclusive education. The whole educational system should be prepared and changed according to the demands of inclusive education.

The research described in this paper reveals only one part of the picture of inclusive education in Serbia, which was the main objective of the research. The results clearly point to different problems related to the implementation of inclusion in Serbia. The research identified some of the problems of implementation of inclusion in Serbia (especially in rural areas), such as insufficient commitment to inclusion in the curriculum, insufficient training of teaching staff, poor working conditions and equipment.

Many children have more than one disability and teachers should be specifically trained to work with those students. The respondents agreed that students with special needs have difficulties in learning the materials determined by the curriculum. One of the solutions they proposed included the involvement of pedagogical assistants as an important affirmative measure of improving the quality of inclusive education. This measure is also proposed in the Strategy of the Development of the Education in Serbia until 2020.

The statistically significant differences that were determined in the research partially or fully confirm the hypothesis that teachers from different schools, places of employment, and gender do not have the same attitudes towards inclusion. The specific context of primary, secondary, urban, and rural schools should also be taken into consideration, especially since inclusion cannot be implemented in the same way in rural regions due to the lack of basic means and facilities.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Project 142-4512165/2019-02 of the Provincial Secretariat for science and technological development, ECAP Vojvodina - https://doi.org/10.13039/5011000052-89.

Authors' Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and provided data for Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. All authors contributed to the collection of the correctly completed questionnaires and the statistical analyses. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

Ainscow M & César M 2006. Inclusive education ten years after Salamanca: Setting the agenda. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21:231. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173412 [ Links ]

Alghazo ME & Gaad EEN 2004. General education teachers in the United Arab Emirates and their acceptance of the inclusion of students with disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 31(2):94-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x [ Links ]

Altinkök M 2017. The effect of movement education based on cooperative learning method on the development of basic motor skills of primary school 1st grade learners. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 16(2):241 -249. Available at http://www.scientiasocialis.lt/jbse/files/pdf/vol16/241-249.Alt%C4%B1nk%C3%B6k_JBSE_Vol.16_No.2.pdf. Accessed 7 November 2019. [ Links ]

Artiles AJ, Kozleski EB & Waitoller FR 2011. Inclusive education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Avramidis A, Bayliss P & Burden R 2000. A survey into mainstream teachers' attitudes towards the inclusion of children with special educational needs in the ordinary school in one local education authority. Educational Psychology, 20(2):190-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663717 [ Links ]

Avramidis E & Norwich B 2002. Teachers' attitudes towards integration / inclusion: A review of the literature. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 17(2):129-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250210129056 [ Links ]

Berry RAW 2010. Preservice and early career teachers' attitudes towards inclusion, instructional accommodations, and fairness: Three profiles. The Teacher Educator, 45(2):75-95. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878731003623677 [ Links ]

Booth T 2000. Progress in inclusive education. In H Savolainen, H Kokkala & H Alasuutari (eds). Meeting special and diverse educational needs: Making inclusive education a reality. Helsinki, Finland: Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. [ Links ]

Cardona CM 2009. Teacher education students' beliefs of inclusion and perceived competence to teach students with disabilities in Spain. The Journal of the International Association of Special Education, 10(1):33-41. Available at https://www.iase.org/Publications/JIASE-2009.pdf#page=35. Accessed 2 November 2019. [ Links ]

Cvjeticanin S, Segedinac M & Segedinac M 2011. Problems of teachers related to teaching optional science subjects in elementary schools in Serbia. Croatian Journal of Education,13(2):184-216. Available at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2b41/b97d816317a72fb7b1c5ff89e08022b4e416.pdf. Accessed 2 November 2019. [ Links ]

Dedej M 2011. The inclusive development of school. Pedagoska Stvarnost, 57(5-6):559-563. [ Links ]

Dupoux E, Hammond H, Ingalls L & Wolman C 2006. Teachers' attitudes toward students with disabilities in Haïti. International Journal of Special Education, 21(3):1-14. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ843614.pdf. Accessed 2 November 2019. [ Links ]

Eiesland NL 1994. The disabled God: Toward a liberatory theology of disability. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press. [ Links ]

Ernst C & Rogers MR 2009. Development of the Inclusion Attitude Scale for high school teachers. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 25(3):305-322. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377900802487235 [ Links ]

European Roma Right Centre 2014. Written comments of the European Roma Rights Centre, PRAXIS and other partner organisations, concerning Serbia. Available at http://www.errc.org/uploads/upload_en/file/serbia-cescr-20-march-2014.pdf. Accessed 9 November 2019. [ Links ]

Fakolade OA, Adeniyi SO & Tella A 2009. Attitudes of teachers towards the inclusion of special needs children in general education classroom: The case of teachers in some selected schools in Nigeria. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 1(3):155-169. [ Links ]

Gal E, Schreur N & Engel-Yeger B 2010. Inclusion of children with disabilities: Teachers' attitudes and requirements for environmental accommodations. International Journal of Special Education, 25(2):89-99. Available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ890588.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2019. [ Links ]

Haq FS & Mundia L 2012. Comparison of Brunei preservice student teachers' attitudes to inclusive education and specific disabilities: Implications for teacher education. The Journal of Educational Research, 105(5):366-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2011.627399 [ Links ]

Heflin LJ & Bullock LM 1999. Inclusion of students with emotional/behavioral disorders: A survey of teachers in general and special education. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 43(3):103-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459889909603310 [ Links ]

Hill JL & Davis AC 1999. Meeting the needs of students with special physical and health care needs. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. [ Links ]

Huang HH & Diamond KE 2009. Early childhood teachers' ideas about including children with disabilities in programmes designed for typically developing children. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 56(2):169-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120902868632 [ Links ]

Langdon CA & Vesper N 2000. The sixth Phi Delta Kappa poll of teachers' attitudes toward the public schools. Phi Delta Kappan, 81(8):607-611. [ Links ]

Lescesen I, Ivanovic-Bibic L, Dragin A & Balent D 2013. Problems of teaching organisation in combined (split) classes in rural areas of the Republic of Serbia. Geographica Pannonica, 17(2):54-59. https://doi.org/10.5937/GeoPan1302054L [ Links ]

Malinen OP, Savolainen H & Xu J 2012. Beijing inservice teachers' self-efficacy and attitudes towards inclusive education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(4):526-534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.12.004 [ Links ]

Milankovic J, Ivkov-Dzigurski A, Dukicin S, Ivanovic-Bibic LT, Lukic T & Kalkan K 2015. Attitudes of school teachers about Roma inclusion in education, a case study of Vojvodina, Serbia. Geographica Pannonica, 19(3):122-129. https://doi.org/10.5937/GeoPan1503122M [ Links ]

Minke KM, Bear GG, Deemer SA & Griffin SM 1996. Teachers' experiences with inclusive classrooms: Implications for special education reform. The Journal of Special Education, 30(2): 152-186. https://doi.org/10.1177/002246699603000203 [ Links ]

Mitrovic R 2012. Strategy for education development in Serbia 2020. Belgrade, Serbia: The Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia. Available at http://erasmusplus.rs/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Strategy-for-Education-Development-in-Serbia-2020.pdf. Accessed 12 November 2019. [ Links ]

Mor Barak ME 1999. Beyond affirmative action: Toward a model of diversity and organizational inclusion. Administration in Social Work, 23(3-4):47-68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v23n03_04 [ Links ]

Odom SL, Buysse V & Soukakou E 2011. Inclusion for young children with disabilities: A quarter century of research perspectives. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4):344-356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815111430094 [ Links ]

Odom SL, Vitztum J, Wolery R, Lieber J, Sandall S, Hanson MJ, Beckman P, Schwartz I & Horn E 2004. Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4(1):17-49. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1471-3802.2004.00016.x [ Links ]

Pavlovic Babic D, Simic N & Friedman E 2018. School-level facilitators of inclusive education: The case of Serbia. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(4):449-465. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1342419 [ Links ]

Psillos S & Curd M (eds.) 2010. The Routledge companion to philosophy of science. London, England: Routledge. [ Links ]

Radic-Sestic M, Radovanovic V, Milanovic-Dobrota B, Slavkovic S & Langovic-Milicvic A 2013. General and special education teachers' relations within teamwork in inclusive education: Socio-demographic characteristics. South African Journal of Education, 33(3):Art. #717, 15 pages. https://doi.org/10.15700/201503070733 [ Links ]

Radivojevic D, Jerotijevic M, Stojic T, Cirovic D, Radovanovic-Tosic L, Kocevska D & Paripovic S 2007. Guide for upgrading inclusive educational practices. Belgrade, Serbia: Fond za otvoreno drustvo. [ Links ]

Ralic Z, Krampac-Grljusic A & Lisak N 2012. Peer tolerance and contentment in relationship with peers in inclusive school. Posters 3: Policy, services, community living, empowerment, rights, ethics, education, employment, quality of life [Special issue]. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(5):528-536. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2010.00597_3.x [ Links ]

Republic of Serbia 2009. Law on the fundamentals of the education system. Official Gazette, 72/2009. [ Links ]

Republic of Serbia 2010. The rulebook on closer instructions for determining the rights to the individual educational plan, its application and evaluation. Official Gazette, 07/2010. [ Links ]

Ryan SM 2014. An inclusive rural post secondary education program for students with intellectual disabilities. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 33(2):18-28. https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051403300204 [ Links ]

Scruggs TE & Mastropieri MA 1996. Teacher perceptions of mainstreaming/inclusion, 19581995: A research synthesis. Exceptional Children, 63(1):59-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299606300106 [ Links ]

Sharma A & Dunay A 2018. An analysis on education for children with disabilities: A qualitative study on head-teachers, teachers and conductor-teachers perception towards inclusion in Hungary. Journal of Advanced Management Science, 6(2): 117-123. https://doi.org/10.18178/joams.6.2.117-123 [ Links ]

Sharma U, Moore D & Sonawane S 2009. Attitudes and concerns of pre-service teachers regarding inclusion of students with disabilities into regular schools in Pune, India. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3):319-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660903050328 [ Links ]

Shoho AR, Katims DS & Wilks D 1997. Perceptions of alienation among students with learning disabilities in inclusive and resource settings. The High School Journal, 81(1):28-36. [ Links ]

Shore LM, Randel AE, Chung BG, Dean MA, Holcombe Ehrhart K & Singh G 2011. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4):1262-1289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385943 [ Links ]

Singal N & Muthukrishna N 2014. Education, childhood and disability in countries of the South - Repositioning the debates. Childhood, 21(3):293-307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568214529600 [ Links ]

Tsokova D & Becirevic M 2009. Inclusive education in Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina: Policy and practice. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 24(4):393-406. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856250903223062 [ Links ]

Vaughn S, Schumm JS, Jallad B, Slusher J & Saumell L 1996. Teachers' views of inclusion. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 11(2):96-106. [ Links ]

Yada A & Savolainen H 2017. Japanese in-service teachers' attitudes toward inclusive education and self-efficacy for inclusive practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64:222-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.005 [ Links ]

York J & Vandercook T 1990. Strategies for achieving an integrated education for middle school students with severe disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 11(5):6-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193259001100503 [ Links ]

Received: 21 June 2018

Revised: 15 March 2019

Accepted: 27 April 2019

Published: 31 December 2019