Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.39 suppl.2 Pretoria Dec. 2019

https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39ns2a1716

Liesel Ebersöhn

Centre for the Study of Resilience and Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. liesel.ebersohn@up.ac.za

ABSTRACT

Educational psychology professionals working in highly unequal societies require training that prepares them to resile professionally irrespective of on-going hardship and a lack of policy-level support. Educational psychology professionals who had participated in a school-based intervention study in a remote high school during their training at university-level were sampled to generate retrospective data on their work engagement experiences during the school-based training. A third of the population who had participated in school-based academic service-learning training (for whom current contact details were available) were purposively sampled (n = 38, female = 31, male = 7) to be representative of diversity (training objective, year group, home language, gender). Subsamples included academic service-learning educational psychology professionals (n = 22, female = 18, male = 4) and educational psychology research graduates (n = 16, female = 13, male = 3). Retrospective qualitative data sources include open-ended questions (verbatim transcriptions of audio-recorded interviews, electronically captured questionnaires), and long-term observation data (visual data and researcher journals) of school-based training. From thematic analysis it appeared that professionals recollect experiencing work engagement (positive emotions, involvement and dedication) during their training with minimal instances of student-related occupational distress ascribed to contextual and diversity constraints. Data was silent on work engagement from research graduates, with an instance of cynicism regarding long-term benefits to clients of short-term services. Academic service learning in a challenging education setting afforded educational psychology professionals training opportunities to be energized, absorbed in developing professional efficacy to address barriers, and empathetically committed to contribute professionally. Implications of training educational psychology professionals for work in transferable challenging school settings are discussed.

Keywords: academic service learning; challenging education setting; educational psychology training; inequality; rural school; work engagement

Introduction and Rationale

Transforming training models to prepare educational psychology professionals to be able to be useful in schools and an education system at risk (extreme adversity and diversity) requires systematic study. Practica are common when training psychologists, but little is documented in this regard (Gross, 2005), with even fewer studies on training psychologists in Africa (Seedat & Lazarus, 2014).

South Africa is the most unequal country in the world (World Bank, 2012) with a triad of challenges in the form of poverty, unemployment, and social inequality (The Presidency, Republic of South Africa, 2014). Consequences of structural disparity, namely health, education, welfare, and livelihood challenges, are intensified in rural spaces. Yet, rural spaces receive fewer resources (Seroto, 2009). Young people live with the intensity of marginalisation and associated trauma (Reddy, James, Sewpaul, Sifunda, Ellahebokus, Kambaran & Omardien, 2013) with implications for psychology services in schools.

The socio-political history of South Africa is evident in an uneven distribution of training opportunities and mental health services (Pillay & Kramers-Olen, 2014). Societal separation means that social responsibility of professionals concerning their role in the well-being of isolated communities is often lacking (Leibowitz, Bozalek, Carolissen, Nicholls, Rohleder, Smolders & Swartz, 2011). Global trends in psychology to foreground the needs of people who have been "marginalized [sic] or disenfranchised within and by psychology based on their ethnic/racial heritage and social group identity or membership" (American Psychological Association [APA], 2003:377) are mirrored in South Africa (Pillay & Kometsi, 2007).

Academic service learning (ASL) has proven to be meaningful when training professionals to work in contexts of diversity and social inequalities (Rohleder, Swartz, Carolissen, Bozalek & Leibowitz, 2008). ASL brings services to people where risk is high, rather than assuming that people are able to reach the support on offer.

Work engagement (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter & Taris, 2008) is used to indicate resilience from an occupational health psychology perspective. The assumption is that the presence of work engagement could buffer against occupational distress and assist educational psychologists to resile in their profession (De Lange EF & Chigeza, 2015).

The purpose of this retrospective study is to establish the extent to which embedding university-based educational psychology training in a remote school afforded opportunities to experience work engagement. The assumption is that such experiences could assist educational psychology professionals to be effective in their careers given an education system with inequality-related trauma. Questions directing the inquiry include: To what extent do the training recollections of educational psychology professionals include instances of work engagement experiences that could prepare them to resile professionally in inequality-related educational settings? How can work engagement experiences of educational psychology professionals inform training in terms of vocational behaviour in challenging contexts? A central premise is to study how to prepare psychologists in schools in challenging contexts in their training to experience work engagement, rather than expected burnout, given the pervasive challenges and scarcity of resources. In order to understand experiences of work engagement of educational psychology professionals in a high-risk education context, this article draws on retrospective experiences of educational psychology professionals who, during their university training, participated in a long-term academic service learning, school-based intervention in a remote high school.

Challenging Rural School Ecologies: Inequality and Trauma

Inequality presents a multiplicity of challenges. Ironically inequality means that in those cases where challenges are the greatest, there is the highest level of need, and resources, including support services, are least available. The prevalence of negative outcomes (as manifested in a range of risk behaviours) is understandable, given the chronic trauma of multiple challenges, accompanying high needs for support, yet limited resources to provide services. Given high unemployment rates (26,5%) (Statistics South Africa [StatsSA], Republic of South Africa, 2017) and limited employment opportunities, the South African poverty line is $40.00 (R586.86) per month. The highest levels of poverty in South Africa are among young people (eighteen- to twenty-four-year age group). The hardship of an unequal society often manifests as trauma symptoms among young people. South African national surveys found a prevalence of at-risk behaviours among the youth, which places school-going young people at risk of a range of diseases and traumatic health outcomes (Reddy et al., 2013). An increase in trauma symptoms nationally in young South Africans was evident when findings of three surveys were compared (2002, 2008 & 2011), and include escalations in reported suicide attempts, non-communicable diseases, intentional and unintentional injuries, as well as less favourable chronic physical health behaviours.

Approximately a third of the 54 million people living in South Africa reside in rural areas (StatsSA, 2014). With regard to poverty and geographical settlement, 55.1% of South Africans living in rural areas are resource scarce. Students from rural areas face cumulative triggering risk factors that predict school failure (Hyman, Aubry & Klodawsky, 2011). Inequality in South Africa means limited availability of and access to basic services (health, water, electricity, sanitation, transport). Objective health challenges include overall poor health, malnourishment (Marrow, Panday & Richter, 2005), and illness (such as HIV&AIDS and tuberculosis) (De Lange, N, Mitchell, Moletsane, Balfour, Wedekind, Pillay & Buthelezi, 2010). Subjective health and well-being are negatively impacted by high levels of crime, gender-based violence - including bullying - as well as substance abuse, high incidences of orphans and child-headed households (Department of Health, Medical Research Council & OrcMacro, 2007), dispersed families with parents and caregivers (especially father figures) absent as they work in cities (Makiwane, Makoae, Botsis & Vawda, 2012), and young people contributing to livelihood activities (Sinay, 2009).

In this context, rural schools do not focus exclusively on teaching and learning but are settings where other essential developmental needs are met: students receive daily meals, care and support from adults, and a sense of belonging from friends.

Resilience and Work Engagement

Psychologists who work in educational settings need to assist young people who live with the trauma of chronic and cumulative environmental demands and resource constraints. Occupational stress and burnout are conceivable for South Africans providing professional support, given incidences of trauma. It follows that students training to work as educational psychology professionals in similar risk contexts would similarly experience occupational stress and burnout during their practical training. Studies have been done in South Africa to investigate training and intervention to prevent burnout and promote wellness with police (Storm & Rothmann, 2003), nurses (Van der Colff & Rothmann, 2009), teachers (Jackson, Rothmann & Van de Vijver, 2006), and professional counsellors (Fourie, Rothmann & Van de Vijver, 2008), but not with educational psychology professionals working in challenging education settings.

This study privileges a resilience focus on work engagement rather than burnout (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá & Bakker, 2002). Work engagement provides a relevant theoretical lens to study how training could prepare educational psychologists to resile and continue to provide services despite unending challenges in an unequal society (De Lange, EF & Chigeza, 2015).

May, Gilson and Harter (2004) posit that engagement in the workplace manifests physically as vigour and positive affect, emotionally as dedication and commitment, and cognitively as absorption and involvement. Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter (2001) explain burnout as the deterioration of work engagement. Schaufeli et al. (2002) explain that at its core, exhaustion is a central indicator of burnout, indicated by mental distance (cynicism, or depersonalisation), and low professional efficacy.

Training Educational Psychology Professionals in South Africa

Educational psychology professionals in South Africa include educational psychologists, as well as graduates who work within the education sector as, for example, policy advisors with nongovernmental organisations, and in schools as educators with expert knowledge. South African educational psychologists provide support for personal issues, educational decisions, career choices, as well as remedial and therapeutic interventions (Health Professions Council of South Africa [HPCSA], 2011). A legacy of apartheid policies mean that mental health services continue to be unequally distributed (Pillay & Kramers-Olen, 2014). Psychology training is moving away from a monocultural lens of privileging a minority, to developing training models that are relevant to the majority of the population (Macleod, 2004). Yet, as is the case elsewhere (Edwards & Sullivan, 2014), psychology services are limited and difficult to access in rural schools (Engelbrecht, 2004).

To centralise socio-cultural context in psychology training (Silbereisen & Ritchie, 2014) a call for a scholarship of engagement is a way for higher education to partner with society to be responsive to challenges (Petersen & Osman, 2013). ASL is credit-bearing, organised training and holds the potential of providing services where the need is high (Landini, Leeuwis, Long & Murtagh, 2014). Students and a community benefit mutually from students addressing an identified community need or doing research on a social issue in a community (Bender, 2008). The use of ASL in unequal settings remains novel and under-researched (Le Roux & Mitchell, 2008).

Methodology

School-Based Intervention Training for Educational Psychology Students Flourishing Learning Youth (FLY)

Table 1 provides an overview of educational psychology students who had participated in a school-based intervention study (Flourishing Learning Youth: FLY) in a remote high school during their training at university level and were sampled to generate retrospective data on their work engagement experiences during the school-based training. FLY was established in 2005 as a school-based intervention partnership between the Centre for the Study of Resilience, University of Pretoria, and remote South African schools (n = 4, high = 2, primary = 2). The twofold purpose was to build knowledge on resilience in a rural school context, and on the intervention side, to provide educational psychology services to young people in the school.

FLY includes annual student groups involved in either academic service learning, or as research students in a decade-long school-based intervention in a South African rural school. Students and supervisors visit the remote school twice annually for two-day (8 hours/day) school-based visits that include clinical training and research activities. The team travels 186 miles (299.34 km) from Pretoria to the remote setting, bringing along the resources they need for services at the school (see Photograph 1).

As part of formative assessment students write reflexive essays on readings focused on resilience and positive psychology, inequality and social justice, rurality and high-risk school settings, psychology within a context of diversity, and monitor their development during training. Student learning is scaffolded via guided, reflexive group sessions before, during and after school visits (see Photograph 2 and 3). Discussions incorporate issues of contextual barriers and resources, professional practice, as well as professional identify.

Besides verbal group-based reflections each student also keeps a reflexive journal.

Contextualizing FLY

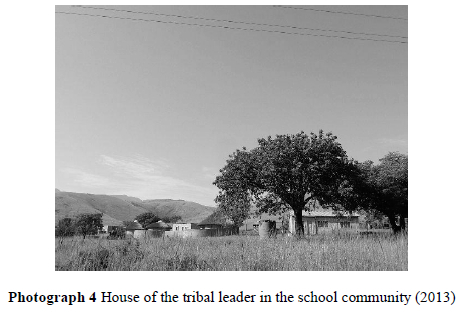

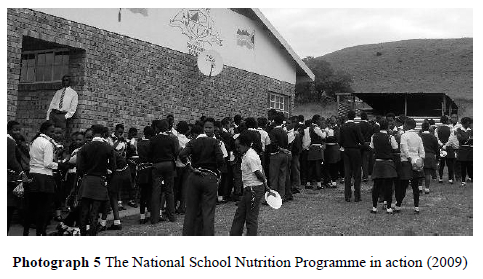

The remote schools are located in the province of Mpumalanga on the border between South Africa and Swaziland. The setting is characterised by agriculture and traditional cultural structures (see Photograph 4 showing the home of the local tribal leader). As is evident in Photograph 5, children receive food daily as part of a national nutrition programme (Department of Education [DoE], 1994). Photograph 6 shows the gravel road leading towards the mountains where the schools are situated. Photograph 7 shows a school-based vegetable garden to supplement feeding, and an AIDS-ribbon signifies the prominence of the pandemic in the daily lives at schools. siSwati is the home language of most of the students and teachers at the school. English is the language of teaching and learning (DoE, 1997).

Educational psychology ASL in FLY

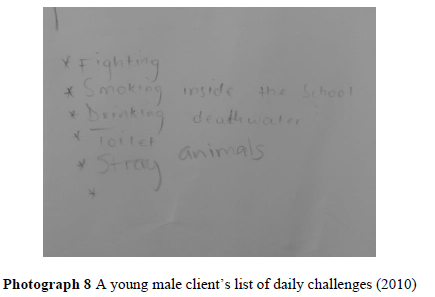

ASL-students provide educational psychology services to Grade 9 learners at the end of an educational phase in which learners are required to choose subjects for the remainder of their schooling. The number of enrolled Grade 9 learners at the rural school has varied between 120 and 80 learners during the decade of the FLY-partnership, and ages have varied between thirteen and twenty-one years. The trauma of being hungry and sad, not always having parents with him, yet just being a young person who enjoys friendship and relaxation, is evident from the list of daily challenges experienced by one young man (Photograph 8).

The first two-day visit is aimed at educational psychology group assessment, and the second at educational psychology group-therapeutic intervention. Grade 9 clients self-select their groups. Photograph 9 shows how students work outdoors with clients in groups scattered around the school grounds. Depending on the enrolment size per year, the sizes of client groups varied between 8 and 12 members. The two visits take place four months apart to afford each ASL-student the opportunity to score and interpret their group of clients' assessment media, and prepare for feedback and therapy. Psychometric measures and therapeutic techniques are mostly not standardised for use with the particular demographic group at the school and ASL-students use constructivist and postmodern techniques to provide services to clients. Based on the outcome of the assessment visit, each psychology student decides on a challenge to address therapeutically with their group during the second visit (Photograph 10).

Educational psychology research in FLY

In FLY educational psychology research students build evidence-based knowledge on resilience in a rural school context (including professional development of teachers). FLY-research students collect data by observing the context, interviewing young people or teachers according to research foci, implementing an intervention in some cases, and returning to validate results with participants. Photographs 11 and 12 show how research students use time at the rural school for data collection (observations, interviews, and questionnaires), consultation with supervisors, and member checking of results with participants. Data on student-related experiences of work engagement and student burnout includes retrospective experiences of educational psychology research students who were immersed in a context of severe challenges in a rural school. Educational psychology research students work within an education system at risk in parallel with professionals such as teachers and educational psychologists - and experiences of work engagement during their fieldwork could arguable prepare and buffer them for future occupational burnout.

Research Methodology

Data constitutes qualitative, retrospective views (Flick, 2009) of the recollections of educational psychology professionals on their work engagement experiences as students in the FLY-partnership in a challenging school ecology. Qualitative retrospective data generation was appropriate, as historical and political context is recognised in terms of individual action, meaning-making, and varied experiences of power, structure, and agency (Hartas, 2010). A constructivist lens was relevant as it allowed for multiple perspectives reflective of the language, socio-economic and cultural diversity profile of the sampled prior educational psychology students (McWilliams, 2012).

Reliable contact details were available for seven previous FLY annual student groups (20072013: n = 102, ASL = 82, research = 20, female = 87, male = 15) (Du Toit, 2016; Machimana, 2017). Prior students were purposively sampled via email to be representative of diversity (training objective, year group, home language, gender). The purposive sample of educational psychology professionals (n = 38, female = 31, male = 7) included subsamples of prior academic service-learning students (n = 22, female = 18, male = 4) and prior research students (n = 16, female = 13, male = 3).

The sample constituted 24% of all ASL-students trained between 2007 and 2013 and 80% of research students who completed their studies in FLY. No research students participated in FLY in 2007 and 2010. In the combined retrospective sample, more recollections of ASL-students are included than that of research students (RS). The overall, as well as ASL and research-student samples, include more female than male students. This gender bias reflects the demographic profile of student enrolment and practicing psychologists in South Africa (Skinner & Louw, 2009). Participants were bilingual with home languages including Afrikaans, Sepedi, Setswana, isiZulu and English. Data was collected in English - the language in which the former students received their university education.

Data generation occurred in 2014 with face-to-face interviews conducted at the University of Pretoria. Sampled educational psychology professionals answered five open-ended questions on their retrospective training experiences in the FLY-partnership in order to gauge their experiences with regard to the research questions: (To what extent do the training recollections of educational psychology professionals include instances of work engagement experiences that could prepare them to resile professionally in inequality-related educational settings? How can work engagement experiences of educational psychology professionals inform training in terms of vocational behaviour in challenging contexts?).

The open-ended questions to elicit retrospective qualitative responses were: (i) What do you know about the partnership?; (ii) What are the strengths of the partnership?; (iii) What are the limitations of the partnership?; (iv) What is required for future planning in the partnership?; and (v) Reflect on your retrospective experiences as student in FLY. Additional data sources include visual data of observations during school-based training.

Participants could opt to complete semi-structured questionnaires, participate in semi-structured, face-to-face interviews or telephonic interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The majority of participants (n = 31, ASL = 17, research = 14) opted to generate retrospective qualitative data via semi-structured questionnaires, some for semi-structured, face-to-face interviews (n = 5, ASL = 4, research = 1), and two for telephonic interviews (ASL = 1, research = 1).

The verbatim transcriptions and electronically captured questionnaire answers were thematically analysed (Braun & Clarke, 2006) by multiple coders to identify patterns on work engagement in the retrospective experiences through processes of open coding and axial coding. Comparisons enabled deeper insights into work engagement patterns in training experiences (Yin, 2014).

The positionality of the author is that of principal investigator in both the FLY-intervention study, as well as the retrospective study that generated data for this article. In addition, the author was the educational psychology lecturer in the practicum module aligned with FLY, and supervisor of research students. Co-researchers were responsible to collect the questionnaire and interview data from participants, transcribe audio-recordings verbatim, and electronically capture questionnaire answers. The author was one of multiple coders engaged in thematic analysis.

Consent for FLY-related research was obtained from the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Education, University of Pretoria, the relevant provincial Department of Basic Education, as well as the school governing body. Annually informed consent is obtained from parents (or caregivers) of the clients, consent or assent from Grade 9 clients, as well as educational psychology students. This includes consent to use visual data of students, clients, training processes and products, as well as the school-community context in the dissemination of research findings.

Limitations, Delimitations and Rigour

A limitation of retrospective designs is that circumstances at the time of data generation could influence or interfere with recounting and analysis of earlier occurrences (Flick, 2009). The use of longterm observation visual data may to some extent increase the credibility of retrospective accounts.

As a retrospective study limits generalisability of findings (Flyvbjerg, 2006), thick descriptions of the context of the academic service learning and research processes are provided to allow possible transferability of findings to similar contexts (Seale, 1999). However, given the non-probability sampling of participants, the quantification of the characteristics of the sample remains a challenge (Battaglia, 2008). Retrospective perspectives from students involved in the initial ASL-years in FLY are lacking.

Although the purposive sample is representative of diversity in the seven annual student groups, female perspectives are overrepresented, as are ASL-student experiences, and non-English home language, bilingual students. The following limitations regarding semi-structured interviews and questionnaires are acknowledged: pre-determined wording and sequences of questions restrict spontaneous unfolding of answers (Hamilton & Corbett-Whittier, 2013) and data is indirect and subjective to participant.

The qualitative and constructivist lenses limited data with regard to subjectivity, given the dy

namic interplay between actions and thoughts of researchers and participants (Yin, 2014). Credibility was strengthened by triangulation of diverse participants; member-checking to establish accuracy with which viewpoints were translated into data; a combination of retrospective accounts together with visual data and researcher journal accounts at the time of the training; as well as thick visual and textual descriptions of the training and context. Dependability is improved by providing an audit trail of documented research data, methods, decisions and outcomes, so that research can be replicated. Multiple year groups of participants and auditability also increases the confirmability of data. The authenticity of data is enhanced by the reflexivity of researchers as accounted for in researcher journals (McMillan & Schumacher, 2010).

Results

Themes on work engagement were evident in the retrospective student experiences and included vigour and positive affect, dedication and commitment, as well as absorption and involvement. The absence of work engagement was indicated by evidence of decreased motivation and distress in the high challenge training context, cynicism and depersonalisation, as well as reduced effectiveness. Work engagement, as well as minimal indications of the absence of work engagement, was evident in ASL-student data across gender and year groups. Research-student data was silent on work engagement with one instance of cynicism indicating a lack of work engagement.

Vigour and Positive Affect: "I Can Actually Do This Outside of the Safety of the University"

The inclusion criterion for this work engagement subtheme was evidence of manifestations of vigour and positive affect (pride, confidence, joy) in the recollections of former educational psychology students given a training context of training in a rural school (May et al., 2004). Former ASL-students (female and male) across year groups commented on positive emotions and energy.

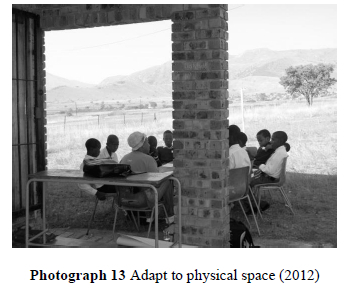

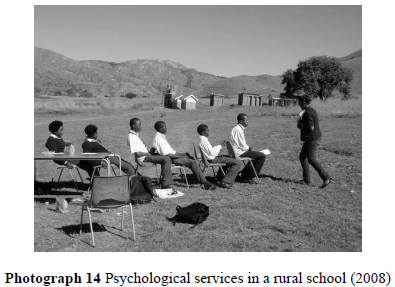

The recollections of educational psychology professionals reflect them feeling energised by insight that they were equipped to provide educational psychology services in a challenging rural school ecology - irrespective of the constraints in a rural school, as portrayed in Photographs 13 and 14. A female 2007 ASL-student stated:

It actually has a lot to play [sic] with my self-esteem and self-confidence and myself as a psychologist, because it taught me that I can actually do this outside of the safety of the university (ASL 2, 116-118); and

So what I really liked is that I learned about myself and I learned that I am capable of doing this career. I am capable of being an educational psychologist in South Africa [sic] (ASL 2, 179-181).

Positive affect was evident in recollecting the pleasure in peer learning (Photographs 15 and 16) when confronted with functioning as an educational psychologist in a challenging educational setting:

I really liked that part [...] to learn from them. Because we encountered several barriers when we went [there]. We had to help each other out. So that was really nice and we learned from each other. And I felt that, because we each have our own individual cases here [university-based training], we don't learn from each other. And it's sometimes nice to see how you can do things differently, or how you can encounter challenges differently. (ASL 1, male, 2011, 30-39)

You get to share your fears and your successes. You get to bounce ideas off one another and truly sense how each person perceives educational psychology as our field of excellence and how it can contribute value to a positive South Africa. The amount of knowledge that we acquire during the time is of inestimable value. (ASL 19, female, 2013,511-512)

I gained from the peer experience. This was challenging because we were working with our own group of clients while at the same time trying to support our peers with another group of clients (ASL 17, female, 2010, 481-482).

The rural school ecology afforded novel experiences amidst diversity and adversity. Recollections indicate appreciation for the benefits of a new training context that required students to be creative and innovative in order to be useful as educational psychology professionals:

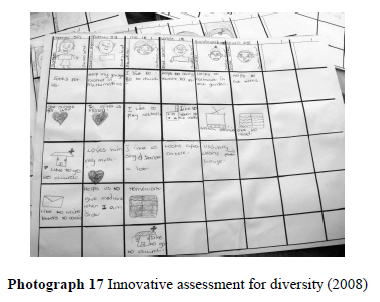

I enjoyed that we did not only used standardised assessments and that we had to be creative in the way we 'assessed' the clients. This is a vital tool as a psychologist, as every client is different (ASL 11, female, 2007, 34-36).

You 're out there with your knowledge. You've got to be [...] actively engaged with the environment, and I think it is an amazing thing to experience in your time separate from the textbooks. So, I think that was something that I felt was a big advantage, which is to see theory meeting practice [...] It's just all this concept in motion. So I quite liked that. (ASL 16, female, 2008, 34-39)

It was a fantastic learning experience. We had to problem-solve on our feet and just work out what we could do when our beautiful laid plans went awry - which they did a bit! (ASL 19, female, 2013, 31-33).

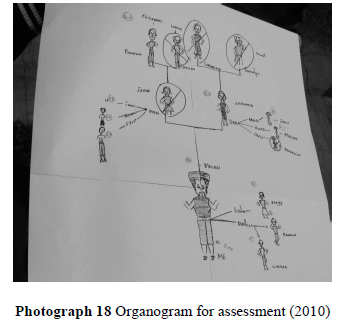

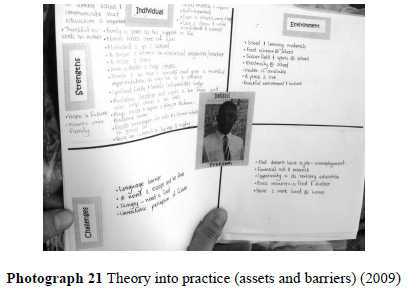

Photographs 17 to 22 show student innovations that enabled the development of professional self-esteem. In the absence of standardised psychometric instruments to assess and provide therapy with the particular client population, students had to develop assessment methods. These assessments had to accommodate multilingualism, limited literacy levels, and had to enable expression and projection of diverse cultural and contextual resources, risks and aspirations. Photographs 20 to 22 show how students used theory on resilience to develop psychological techniques.

Dedication and Commitment: "These Skills I Use on a Daily Basis"

The inclusion criterion for this work engagement subtheme was evidence that former educational psychology students identified with work-related educational psychology activities in a rural school - as indicated by emotional manifestations of dedication and commitment (May et al., 2004). Female and male ASL-students across year groups commented on dedication and commitment.

In many instances former students expressed that their training in a challenging educational setting enabled them to be committed in educational psychology careers in diverse and adverse ecologies (synonymous with Africa). Photographs 23 and 24 and the following extract show the awareness that diversity, and in particular its multilingualism, does not necessarily imply distress:

This experience enabled me to work more effectively in my current situation. I work here in Tanzania with people - expats and local Tanzanians - with different cultures and languages than mine [...] the people first of all speak a different language than me. Their English understanding is limited and the different tribes in Tanzania is [sic] very serious about their culture [...]. So the [training] taught me how to be flexible and respectful regarding my basic interactions, psychological interventions, communications and relationship building. These skills I use on a daily basis. (ASL 6, female, 2009, 31-41)

Participants expressed that their scope of proficiency to work with a diverse client base was expanded, including gender, age, ethnicity, and urban-rural spaces:

It was very difficult for me to work with teenage girls! However, now that I work in a school, and I have to work with all children, I am glad I had the experience and know enough about myself and them to be able to work productively with any age and gender. (ASL 12, female, 2013, 58-62) The vigorous contribution that the [training] makes in [. ] transformation and initiative to promote relationships. To almost reunite the strangeness of people who live in a different cultural and social environment and to bridge that strangeness and to show that we are on the same side in a country that has vast variety and diversity. (ASL 1, male, 2011, 27-31)

The experience has stuck with me, and I take the lessons learned into my current work environment, where I consult students from all over the country, and I realise that what we take for granted in the city is something that is considered a luxury in a rural community. (ASL 9, male, 2011, 180-184) I remember our discussions on being mindful that when we enter the school and commute from a privileged position. And that there are likely power relations that we would need to manage. It was a fantastic learning experience (ASL 17, female, 2010, 462-465).

I enjoyed going [...] and meeting people and sharing their resilience within their circumstances (ASL 9, male, 2011, 180-184).

Absorption and Involvement: "I Learned About the Importance of Social Justice, Teamwork, and Professionalism in all Settings"

The inclusion criterion for this work engagement subtheme was evidence of cognitive manifestations of absorption and involvement by former educational psychology students, while offering psychology services in a rural school (May et al., 2004).

Female and male ASL-students across year groups commented on absorption and involvement.

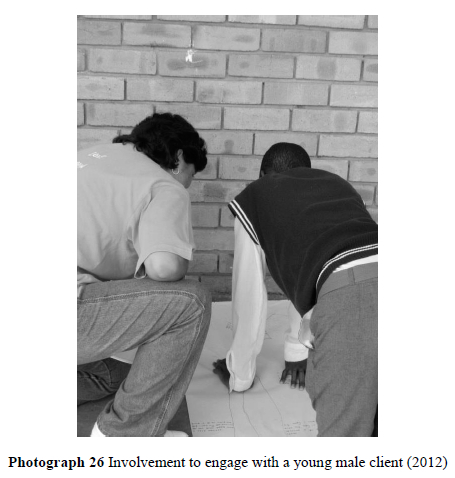

Participants recalled capacity for professional efficacy acquired during their training. Their absorption and involvement in providing service as educational psychologist are apparent in Photographs 25 and 26. Their reported effectiveness included a range of competences required to be an educational psychology professional for a diverse client base:

Space and work areas were a problem, but as a group my clients and I adjusted (ASL 7, 34). I have definitely learned how to manage cultural difference better [.] as in the moment I struggled but on the long term - when I thought back -1 realised how and what to do in situations like this (ASL 14, female, 2013, 62-64).

I learned about the importance of social justice, teamwork, and professionalism in all settings (ASL 13, female, 2012, 247).

I was learning a lot during that work exposure about issues of social justice and the needs of the [clients] at a rural school (ASL 11, female, 2009, 218-219).

Working with young people in the remote school was different from working with clients in the city. Participants indicated that the diversity profile of clients in a rural school, required adaptations to their choices during assessment:

You learn about dynamic assessment which shows you how important it is in our [...] practice as psychologists (ASL 21, female, 2009, 28-30).

It also amazed me that when working in groups it was sometimes the 'small things' that made a big difference - who sat where, how I interacted with the group versus with individuals, and the importance of incorporating formal [standardized] and informal activities (ASL 7, male, 2007, 2931); and

It truly brought the concept of alternative, asset-based assessment home to me (ASL 7, male, 2007, 35).

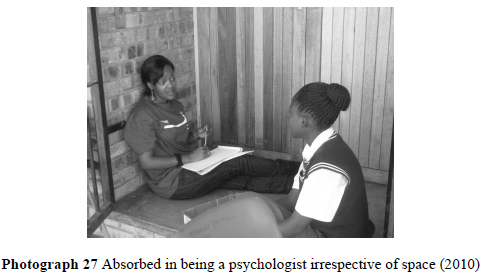

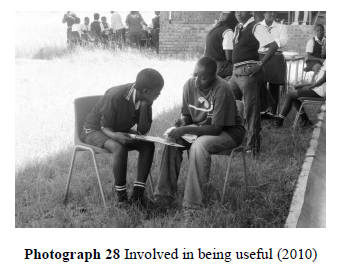

Besides tailoring their services to diversity requirements in a rural school, participants also expressed how they were able to develop their basic range of competencies in order to be relevant as psychologists - irrespective of the space in which they provided services (as is illustrated in Photographs 27 and 28):

The experience helped me to develop insight into how to be a psychologist - learning how to step back and reflect often (ASL 17, female, 2010, 478479).

I gained from using different types of activities with my client group, from learning to be flexible and adaptable, taking my cue from the clients and learning to let clients set the pace (ASL 19, female, 2013, 34-36).

The Absence of Work Engagement: "I Was Not Sure if My Message Reached Them"

Minimal contraindicators of work engagement and indicators of work-related distress (May et al., 2004) were apparent - as indicated by evidence of distress and decreased motivation, given time and multilingualism barriers; cynicism about the effectiveness of services provided; and concerns about a lack of professional efficacy to provide relevant support in a remote space with high levels of poverty and unemployment. Contraindicators of work engagement were evident for both genders and across year groups for an ASL, and a former male research student.

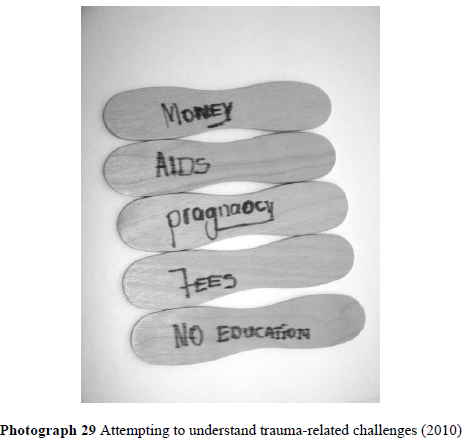

Several participants were distressed about the multilingual client-psychologist barrier in being an educational psychologist in the rural school. This is evident in the extract below, as well as in Photographs 29 and 30, which show attempts by students to create opportunities for clients to project their experiences in interactive ways, and using more than one language to elicit information from clients:

I am a black foreigner. So I do not speak any of the South African languages. I felt bad when [clients] spoke something as we were interacting and I was not able to understand what they were saying (ASL 15, female, 2007, 358-360).

I really wanted to use the opportunity to bring the [clients] and opportunity of growth, but I was not sure if my message reached them (ASL 9, male, 2011, 42-43).

Less time was spent with clients in the rural school than with clients in the city. The university-based training follows a one-on-one training model with days spent on individual assessment, feedback to the client and their family, and then additional days for therapeutic intervention. The participants were aware of the high need caused by resource constraints (Photograph 31), and the absence of psychology services in the isolated school (Photograph 32). The limited time at the rural school appeared to have caused participants concern. They were unfamiliar with group-based work over short periods. They were worried that the limited time of educational psychology services would be sufficiently useful to clients:

I felt that I did not have enough time to do everything that I want to do with the [clients] (ASL 15, female, 2007, 361-362).

I remember doing soul-searching whether we were just opening up expectations, hopes of [clients] and their families, and then leaving them (ASL 17, female, 2010, 457-459).

The limited time possibly influences the effect [. ] in that the follow-through of the skills that we were taught cannot be entirely facilitated (ASL 21, female, 2009, 15-17).

Instances of cynicism were apparent as participants did not believe that inferences could be made about the usefulness of educational psychology services without evidence of clients' academic progress and career choices in later years. They were, given the diversity, sceptical about the effectiveness of educational psychology:

The service provided is essential and necessary. However, it cannot be known how the [clients] benefitted from the information provided by [us] [...], especially against the background that the [.] students who apply for [.] careers are no longer part of the [services]. (RS 9, male, 2011, 60-64)

Remember, firstly as human beings we are not always receptive to learning from people that we 'don't understand' or that we believe 'don't understand me or my world' (ASL 14, female, 2013, 3234).

Participants were exposed to the challenges of limited resources (physical, financial, services) in a rural school - Photographs 33 and 34. Given the resources constraints, distance to services and high levels of poverty and unemployment in school-community households, one participant appeared concerned about a lack of professional efficacy when providing educational psychology services in a remote school:

I felt disheartened that we provided [clients] with access to information about career paths, et cetera, but not on how to apply or access bursaries or financial aid for further studies or a means to apply for jobs (ASL 8, female, 2010, 55-57).

Making Sense of Themes on Work Engagement in Retrospective Training Experiences

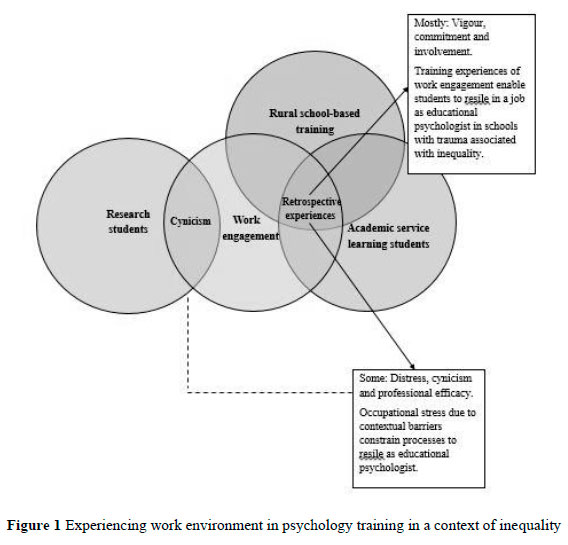

Figure 1 illustrates the experiences of work engagement in training of former educational psychology students in an education setting with trauma associated with high inequality. Research data was silent on evidence of work engagement, and cynicism was present with a male research student. As the training of research students entailed research capacity development, these participants did not engage in close, hands-on educational psychology services with young people as ASL-students did. The differences in training opportunities between these groups of students plausibly impacted on the possibility of research students not experiencing work engagement. A different study might explore whether research students experienced work engagement as researchers when conducting their compulsory research in a rural school.

The recollections of former students, irrespective of gender or training year, indicate that the services they provided to groups of young people during their educational psychology training at a rural school enabled them to experience work engagement. Work engagement was possible in a highly challenged educational setting. Despite a setting that epitomises the negative spectrum of limited resources, isolation from services, socio-economic and health-related challenges, former educational psychology students recollect experiences of positive emotions, absorption in their work and dedication to resile as educational psychology professionals in an unequal society.

Barriers to work engagement experiences of ASL-students were also evident in recollections. Barriers were contextual and associated with providing services in a remote school. Recollections indicate experiences of being distressed during training that professional efficacy was impacted negatively due to limited time with clients, possible misunderstandings because of language differences between educational psychology students and clients, and the possibility that clients' aspirations would be stymied by financial and educational opportunity constraints. The long-term effect of such contextual barriers on transactional-ecological processes that prevent occupational stress and support educational psychology professionals to resile in an unequal society requires further investigation.

Discussion

To What Extent do the Training Recollections of Educational Psychology Professionals Include Instances of Work Engagement Experiences that could Prepare Them to Resile Professionally in Inequality-Related Educational Settings?

From their retrospective experiences, it is apparent that training in a high-risk and high-need South African rural school afforded educational psychology students with opportunities to experience work engagement. This is in line with meta-analysis studies on service learning (Conway, Amel & Gerwien, 2009) that found changes for personal, social, and citizenship outcomes. Former ASL-students recalled that they were absorbed in the realisation that they could be effective professionally in an unfamiliar space, where the languages between them and their clients were different, the infrastructure to assess and provide therapy was sparse, and the young people came from homes with little income and much loss. They remembered feeling empathy and commitment to contribute professionally to the development of young people who live on the margins of inequality, and who would otherwise not have access to services. Former ASL-students recollected feeling satisfied and energised in the knowledge that they were able to provide psychological services to the young people in a rural school.

As with the former ASL-students, work engagement was also evident among non-professional counsellors (Fourie et al., 2008) and teachers (Jackson et al., 2006) working in equally resource-constrained settings in South Africa. A review on the theory of preventative stress management found that training from a salutogenic, positive psychology frame enables eustress rather than occupational distress (Hargrove, Quick, Nelson & Quick, 2011). Theoretical preparation and debriefing based on resilience, positive psychology, and the asset-based approach potentially scaffolded students' meaning-making towards eustress.

The burden of taxing workloads and limited resources has been found to impact negatively on work engagement, and specifically on psychologists' professional efficacy (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). By way of contrast, the recollections of former ASL-students in the current study reflect absorption and involvement in their capacity to apply learning in a highly challenged school setting. It is possible that the peer-learning nature, an opportunity to apply theory in a school setting with clients in dire need of support, and the short-term model of services promoted efficacy experiences. In addition, as students, participants in this study were not exposed to the extreme levels of hardship over an extended period of time.

Lundy (2007) also found that service learning increased empathy among volunteers. The school-based time with young clients appeared to engender confidence in psychologists in training that they could commit to working with a diverse spectrum of clients. Similar trends were apparent in a study by Vera and Speight (2003), who found that multicultural competence was possible within a broader agenda of social justice in psychology. In this way, training may prompt dedication and commitment to psychology that privileges the disenfranchised majority when such training is founded on social justice efforts to be useful to isolated people living with extreme hardship.

As discussed earlier, the silence on work engagement in recollections of research students requires further investigation.

How Can Work Engagement Experiences of Educational Psychology Professionals Inform Training in Terms of Vocational Behaviour in Challenging Contexts?

Academic service learning deliberately positioned in a school ecology characterised by high adversity and diversity enables students to experience work engagement. Tugade and Fredrickson (2004) found that positive emotions enable resilience. It follows that such experiences prepare educational psychology professionals to work in an ecology of adversity and diversity. Prospective investigation is necessary to strengthen this assertion.

In their meta-analysis Eyler, Giles, Stenson and Gray (2001) found benefits of service learning to include, inter alia, multicultural understanding and a range of skills conducive to professional practice (critical thinking, interpersonal skills, leadership skills, self-confidence). Work engagement was supported by intentional activities where students were intentionally tasked with recounting experiences of professional efficacy during their school-based training. Work engagement because of service learning was indicated by former ASL-students: (i) feeling confident that they were capable of providing services in an unfamiliar and highly challenged school space; (ii) enjoying the presence of peer learning was present; (iii) feeling involved when they could see the value of using theory to support clients; (iv) being energised by the need to be creative to innovate and adapt assessment and therapy strategies with young people for whom standardised methods were not available; (v) feeling empathy and commitment to provide services where none would be provided otherwise; and (vi) being self-assured when they remembered feeling able to deal with challenges of multilingualism and diversity.

Evidence of student-related burnout (distress, reduced efficacy, cynicism) was less evident in recollections. Findings show that burnout (the absence of work engagement) was apparent when students doubted their professional efficacy because of constraints characteristic of rurality, the constraints of the particular service model, and concerns about efficacy for a diverse client base. Burnout, depersonalisation, cynicism, and distress often occur among students trained as medical professionals (Prinz, Hertrich, Hirschfelder & De Zwaan, 2012). The retrospective nature of the current study could have biased former students to romanticise the camaraderie and adventure of learning together in an unfamiliar space as they recounted their awakening confidence in their own professional efficacy. Instances of distress, dysfunctional work attitudes and behaviour, and cynicism may have been more pronounced if similar questions were asked during their training. This requires further study.

With regard to diversity between professionals and clients, former educational psychology students were most vocal about language as a constraint in providing effective services in a rural school, rather than class, gender, age, ethnicity, place constraints, or group size.

Several lessons for academic service learning, and school-based research follows from the findings. In education landscapes at risk work engagement experiences integrated into training and research could be protective to enable educational professionals to resile professionally in their future careers. Future training in similar multilingual societies may be to include related theoretical curriculum activities prior to school visits, as well as on-site debriefing about strategies to deal with multilingualism. Educational psychology students may require support in understanding how to determine effect of services for a client when they are unable to follow up due to distance and time constraints. Theoretical preparation regarding resilience, resources, and assets, as well as constructivist and postmodern assessments were beneficial to assist students to be creative during assessment and therapy and be responsive to the contextual and diversity needs of young clients in a rural school.

Conclusion

The geopolitical placement of South Africa means that schools are spaces of high diversity, having to accommodate multilingualism and multiple cultural backgrounds. In addition, a postcolonial and apartheid history means that the socio-cultural perspectives, as well as the socio-economic realities of the majority of South Africans are not accommodated in psychological assessment and therapeutic interventions. Unequal resource distribution means that opportunities for learning, development, and well-being are negligible -especially in rural schools -with consequent trauma at this extreme end of resource scarcity. Child development is negatively impacted by high incidences of tuberculosis, people being infected by or living with HIV and AIDS, and malnourishment. Family systems are disrupted with children heading households when their parents pass away, or work in cities. Educational support to children is hampered by low literacy rates of parents or caregivers, and by the fact that homes are not literacy-rich spaces and few public libraries are available.

Burnout can be expected in educational psychology professionals who work in education settings with inadequate access to limited services and clients with multiple well-being and learning needs. However, academic service learning provided a "better-than-expected" training outcome for educational psychology students to experience work engagement in their training as preparation to resile in their future careers despite inequality challenges. Academic service learning provides a platform for educational psychology students to know that they can feel committed and be involved in the full continuum of being an educational psychology professional in education spaces in an unequal society, buoyed by experiences of vigour and positive emotions. Educational psychology professionals could experience professional efficacy despite diversity challenges of multilingualism and multi-culturalism, contextual barriers of clients living with trauma of scarce opportunities and isolation from services, training constraints of limited time with clients, and imperfect spaces in a rural school, to provide confidential services. Further study is required to investigate both the relevance of research training of educational psychology students in challenging school contexts, as well as work engagement experiences when working with trauma of extreme hardship over an extended period of time.

Notes

i. Published under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

References

American Psychological Association 2003. Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58(5):377-402. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.5.377 [ Links ]

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP & Taris TW 2008. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 22(3):187-200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802393649 [ Links ]

Battaglia MP 2008. Nonprobability sampling. In PJ Lavrakas (ed). Encyclopaedia of survey research methods (Vol. 2). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Bender CJG 2008. Curriculum enquiry about community engagement at a research university. South African Journal of Higher Education, 22(6):1154-1171. Available at https://journals.co.za/docserver/fulltext/high/22/6/high_v22_n6_a3.pdf?expires=1569663567&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=BF52D76653F8283DEB35CFE1A097BEFE. Accessed 28 September 2019. [ Links ]

Braun V & Clarke V 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2):77-101. [ Links ]

Conway JM, Amel EL & Gerwien DP 2009. Teaching and learning in the social context: A meta-analysis of service learning's effects on academic, personal, social, and citizenship outcomes. Teaching of Psychology, 36(4):233-245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280903172969 [ Links ]

De Lange EF & Chigeza S 2015. Fortigenic qualities of psychotherapists in practice. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 25(1):56-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2014.997039 [ Links ]

De Lange N, Mitchell C, Moletsane R, Balfour R, Wedekind V, Pillay D & Buthelezi T 2010. Every voice counts: Towards a new agenda for schools in rural communities in the age of AIDS. Education as Change, 14(sup1):S45-S55. https://doi.org/10.1080/16823206.2010.517916 [ Links ]

Department of Education (DoE) 1994. The National School Nutrition Programme (NSNP). Pretoria, South Africa: Author. [ Links ]

Department of Education 1997. Language in education policy. Government Gazette, 18546, December 19. [ Links ]

Department of Health, Medical Research Council & OrcMacro 2007. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health. Available at https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR206/FR206.pdf. Accessed 28 September 2019. [ Links ]

Du Toit I 2016. Retrospective experiences of academic service learning students in a rural school-higher education partnership. MEd dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Edwards LM & Sullivan AL 2014. School psychology in rural contexts: Ethical, professional, and legal issues. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 30(3):254-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2014.924455 [ Links ]

Engelbrecht P 2004. Changing roles for educational psychologists within inclusive education in South Africa. School Psychology International, 25(1):20-29. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0143034304041501 [ Links ]

Eyler J, Giles DE Jr, Stenson CM & Gray CJ 2001. At a glance: What we know about the effects of service-learning on college students, faculty, institutions and communities, 1993-2000: Third edition. Higher Education. Paper 139. Available at https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://scholar.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1137&context=slcehighered. Accessed 27 September 2019. [ Links ]

Flick U 2009. An introduction to qualitative research (4th ed). London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Flyvbjerg B 2006. Five misunderstandings about casestudy research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2):219-245. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1077800405284363 [ Links ]

Fourie L, Rothmann S & Van de Vijver FJR 2008. A model of work wellness for non-professional counsellors in South Africa. Stress & Health, 24(1):35-47. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1163 [ Links ]

Gross SM 2005. Student perspectives on clinical and counseling psychology practica. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(3):299-306. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.299 [ Links ]

Hamilton L & Corbett-Whittier C 2013. Using case study in education research. London, England: Sage. [ Links ]

Hargrove MB, Quick JC, Nelson DL & Quick JD 2011. The theory of preventive stress management: A 33-year review and evaluation. Stress & Health, 27(3):182-193. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1417 [ Links ]

Hartas D 2010. The epistemological context of quantitative and qualitative research. In D Hartas (ed). Educational research and inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London, England: Continuum International Publishing Group. [ Links ]

Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) 2011. Regulations defining the scope of profession of psychology. Government Gazette, 34581, September 2. [ Links ]

Hyman S, Aubry T & Klodawsky F 2011. Resilient educational outcomes: Participation in school by youth with histories of homelessness. Youth & Society, 43(1):253-273. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0044118X10365354 [ Links ]

Jackson LTB, Rothmann S & Van de Vijver FJR 2006. A model of work-related well-being for educators in South Africa. Stress & Health, 22(4):263-274. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1098 [ Links ]

Landini F, Leeuwis C, Long N & Murtagh S 2014. Towards a psychology of rural development processes and interventions. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24(6):534-546. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2187 [ Links ]

Leibowitz B, Bozalek V, Carolissen R, Nicholls L, Rohleder P, Smolders T & Swartz L 2011. Learning together: Lessons from a collaborative curriculum design project. Across the Disciplines, 8(3). [ Links ]

Le Roux A & Mitchell J 2008. A reflection on challenges facing volunteerism in South Africa. Commonwealth Youth and Development, 6(1):55-64. [ Links ]

Lundy BL 2007. Service learning in life-span developmental psychology: Higher exam scores and increased empathy. Teaching of Psychology, 34(1):23-27. [ Links ]

Machimana EG 2017. Retrospective experiences of a rural school partnership: Informing global citizenship as a higher education agenda. PhD thesis. Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria. [ Links ]

Macleod C 2004. South African psychology and 'relevance': Continuing challenges. South African Journal of Psychology, 34(4):613-629. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F008124630403400407 [ Links ]

Makiwane M, Makoae M, Botsis H & Vawda M 2012. A baseline study on families in Mpumalanga (Commissioned by the Mpumalanga Department of Social Development, July). Available at http://repository.hsrc.ac.za/bitstream/handle/20.500.11910/3332/Mpumalanga%20family%20study%2030-07-2012.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 29 September 2019. [ Links ]

Marrow S, Panday S & Richter L 2005. Young people in South Africa in 2005: Where we 're at and where we 're going. Johannesburg, South Africa: Umsobomvu Youth Fund. [ Links ]

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB & Leiter MP 2001. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52:397422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.L397 [ Links ]

May DR, Gilson RL & Harter LM 2004. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1):11 -37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892 [ Links ]

McMillan J & Schumacher S 2010. Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [ Links ]

McWilliams SA 2012. Mindfulness and extending constructivist psychotherapy integration. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 25(3):230-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720537.2012.679130 [ Links ]

Petersen N & Osman R 2013. An introduction to service learning in South Africa. In R Osman & N Petersen (eds). Service learning in South Africa. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Pillay AL & Kometsi MJ 2007. Training psychology students and interns in non-urban areas. In N Duncan, B Bowman, A Naidoo, J Pillay & V Roos (eds). Community psychology: Analysis, context and action. Cape Town, South Africa: UCT Press. [ Links ]

Pillay AL & Kramers-Olen AL 2014. The changing face of clinical psychology intern training: A 30-year analysis of a programme in KwaZulu- Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 44(3):364-374. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0081246314535683 [ Links ]

Prinz P, Hertrich K, Hirschfelder U & De Zwaan M 2012. Burnout, depression und depersonalisation -Psychologische faktoren und bewältigungsstrategien bei studierenden der zahn-und humanmedizin [Burnout, depression and depersonalisation - Psychological factors and coping strategies in dental and medical students]. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Ausbildung, 29(1). Available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3296106/pdf/ZMA-29-10.pdf. Accessed 23 September 2019. [ Links ]

Reddy SP, James S, Sewpaul R, Sifunda S, Ellahebokus A, Kambaran NS & Omardien RG 2013. Umthente Uhlaba Usamila - The 3rd South African National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey 2011. Cape Town, South Africa: South African Medical Research Council. Available at https://africacheck.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/3rd-Annual-Youth-Risk-Survey-2011.pdf. Accessed 4 October 2019. [ Links ]

Rohleder P, Swartz L, Carolissen R, Bozalek V & Leibowitz B 2008. "Communities isn't just about trees and shops": Students from two South African universities engage in dialogue about 'community' and 'community work'. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 18(3):253-267. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.918 [ Links ]

Schaufeli WB & Bakker AB 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3):293-315. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.248 [ Links ]

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V & Bakker AB 2002. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3:71-92. Available at https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/178.pdf. Accessed 22 September 2019. [ Links ]

Seale C 1999. Introducing qualitative methods: The quality of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857020093 [ Links ]

Seedat M & Lazarus S 2014. Community psychology in South Africa: Origins, developments, and manifestations. South African Journal of Psychology, 44(3):267-281. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0081246314537431 [ Links ]

Seroto J 2009. The impact of South African legislation (1948-2004) on black education in rural areas: A historical educational perspective. PhD dissertation. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. Available at http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/1915/thesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 22 September 2019. [ Links ]

Silbereisen RK & Ritchie PLJ 2014. Introduction to psychology education and training: A global perspective. In RK Silbereisen, PLJ Ritchie & J Pandey (eds). Psychology education and training: A global perspective. New York, NY: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Sinay E 2009. Academic resilience: Students beating the odds. Research Today, 5(1):394-416. [ Links ]

Skinner K & Louw J 2009. The feminization of psychology: Data from South Africa. International Journal of Psychology, 44(2):81-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590701436736 [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa 2014. Statistical release P0302: Mid-year population estimates 2014. Pretoria, South Africa: Author. Available at https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022014.pdf. Accessed 4 October 2019. [ Links ]

Statistics South Africa, Republic of South Africa 2017. Quarterly Labour Force Survey - QLFS Q4:2016. Available at http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=9561. Accessed 20 September 2019. [ Links ]

Storm K & Rothmann S 2003. A psychometric analysis of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey in the South African Police Service. South African Journal of Psychology, 33(4):219-226. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F008124630303300404 [ Links ]

The Presidency, Republic of South Africa 2014. The Presidency Annual Report 2013/2014. Pretoria: Author. Available at https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201410/presidencyannualreport2013-2014.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2019. [ Links ]

Tugade MM & Fredrickson BL 2004. Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2):320-333. [ Links ]

Van der Colff JJ & Rothmann S 2009. Occupational stress, sense of coherence, coping, burnout and work engagement of registered nurses in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 35(1):Art. #423, 10 pages. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v35i1.423 [ Links ]

Vera EM & Speight SL 2003. Multicultural competence, social justice, and counseling psychology: Expanding our roles. The Counseling Psychologist, 31(3):253-272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000002250634 [ Links ]

World Bank 2012. South Africa economic update: Focus on inequality and opportunity. Washington, DC: Author. Available at http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/233241468164377382/pdf/715530NWP0P1310lete0with0cover00726.pdf. Accessed 5 September 2019. [ Links ]

Yin RK 2014. Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Received: 4 September 2018

Revised: 29 January 2019

Accepted: 16 April 2019

Published: 31 December 2019