Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

South African Journal of Education

On-line version ISSN 2076-3433Print version ISSN 0256-0100

S. Afr. j. educ. vol.34 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2014

Framing of school violence in the South African printed media - (mis)information to the public

Lynette Jacobs

School of Education Studies, University of the Free State, South Africa jacobsl@ufs.ac.za

ABSTRACT

The way in which the media report on school violence influences public perceptions, gives rise to particular attitudes and can influence decisions by policy makers. The more frequently an issue is presented in a specific way, the more likely it is for readers to perceive the media's version as the truth. Although news is assumed to be reliable, comprehensive and unprejudiced, journalism can be questioned. This study explores how school violence is framed in the South African print media. A framing analysis was done of 92 articles that appeared in 21 different public newspapers during one year. I found that the way in which the public is informed encourages the perception of school violence as being an individual, rather than a societal, problem and encourages the acceptance of assumptions and stereotypes. Typical 'blood-and-guts' reporting is popular, while issues such as emotional and sexual violence in schools appear largely unnoticed by journalists. I argue that the main frames provided to readers in South African newspapers fail largely to elicit social responsibility, while at the same time promoting civic indifference.

Keywords: emotional violence; media framing; physical violence; school violence; sexual violence; social responsibility

Introduction

The constitutional right to freedom from violence is mutatis mutandis applicable to schools as places of education within the social structure of South African society (Republic of South Africa (RSA), 1996:Section 12(1)(c)). The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa specifically affirms the right of children to be protected from any form of maltreatment (RSA, 1996:Section 28(1)(d)), and their right to education (RSA, 1996:Section 29). The violent reality in South African schools is, however, not congruent with these and other fundamental human rights (Prinsloo, 2005). Masitsa (2011:164) argues that violence is "deep-rooted" in South African schools.

Violence is by no means a simple phenomenon and numerous definitions exist. Violence is often seen as the intentional use of brute force or power aimed at harming another, including intimidation or coercion by the threat of force (Henry, 2000). There are, however, other elements of harm that can also be classified as violence, such as emotional or psychological pain (Krug, Mercy, Dahlberg & Zwi, 2002), manipulation (Henry, 2000) and deprivation, as well as neglect (Krug et al., 2002). What sets school violence apart is the context of the school, its fundamental purpose, the educational activities associated with the school, the school community and school property (De Wet, 2007). Informed by the various views on violence and school violence and based on the definition of violence by the World Health Organisation (cf. Krug et al., 2002:1084), I demarcate school violence as follows (Jacobs, 2012:24):

School violence refers to any intentional use of physical or other force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group, at school, that either results in or has the likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation. It thus includes any intended use of psychological power or physical force with the aim to harm another physically or emotionally. It includes manipulation and coercion as well as rejection, and can take place during or outside school hours, during class times and breaks, at school-related events (sport, cultural and social), as well as while commuting to and from school.

School violence in its countless forms is a constant threat for role-players in current South African schools (Kgobe & Mbokazi, 2008:63). Physical violence, such as beating, kicking and punching one another, as well as physical assault, in various degrees, frequently occur in our schools, while psychological violence in schools is also widespread (De Wet, 2005:84). Direct verbal victimisation is, for instance, prevalent in secondary schools (De Wet, 2005:84), while intimidation also takes place (Masitsa, 2011:170). Various forms of sexual violence are common in schools, including sexual name-calling and suggestive storytelling, unwanted sexual comments (De Wet & Jacobs, 2009:63) and physical, sexual harassment, such as unwanted kissing, touching, grabbing and pinching in a sexual way (De Wet, Jacobs & Palm-Forster, 2008:106-107). Various forms of deprivation, such as stealing personal belongings (De Wet, 2003a:88), and disregard for a person's property (Marais & Meier, 2010:50) are common in schools. Hadebe (2000:67) furthermore argues that educators deprive learners of quality schooling through their negative attitudes towards their work, their continual absenteeism, their lateness, and their general lack of discipline. As research indicates that school violence is rife, it is essential for society to be aware of this problem, and Oosthuizen and De Waal (2005:5) urge role-players to cooperate to combat this violence.

The role of the media

The print media regularly inform the public about incidences of school violence; for instance, learners being assaulted (Maphumulo, 2010), raped (Davids & Makwabe, 2007) and killed (Fredericks & Mposa, 2012), by using scissors, knives and firearms (Business Day, 2006; Carstens, 2006; Seale, 2008). Educators and learners are portrayed as both victims and perpetrators (Fitzpatrick, 2006; Govender, 2009).

The regularity with which such newspaper articles appear confirms that school violence is a newsworthy problem in South Africa, and raises public awareness. Media reporting on issues has the power to shape the views of readers regarding what is of importance, and the concomitant public awareness has the potential to influence policy making (Bullock, 2007; Carlyle, Slater & Chakroff, 2008; Snyman, 2007). De Wet (2003b), however, points out that media reports are not necessarily unbiased. Whilst news is socially constructed, it is constructed based on the needs of journalists, news agencies and consumers, and it is limited by economic imperatives and constraints (Bullock, 2007; Jones, 2005). Although Froneman (in De Wet, 2009) emphasises that news articles are supposed to provide news accurately, the lack of good journalism is pointed out by Jones (2005:153) (emphasis in original):

Every journalist knows intuitively which terms to use when characterising the favoured and unfavoured players in a situation ... we plan, they plot. We form strategies, they conspire ... We defend ourselves, they attack. Therefore, while school violence is an emotive public issue and receives wide media coverage in South Africa, the coverage may be distorted.

Media studies on (school) violence

Studies focusing on media reporting of school violence in South Africa and beyond are limited. I have, therefore, also drawn from media studies on the portrayal of other kinds of violence in South African communities to inform this study, namely, on how the violent crime in Gauteng is reported, how the xenophobic attacks of 2008 were covered in the print media, as well as how violent conflict in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) is portrayed in the media.

In a qualitative content analysis of newspaper articles on school violence published between June and September 2008, De Wet (2009) focused specifically on how victims and perpetrators are portrayed in the South African print media. She found that while harsh pictures of perpetrators of school violence regularly appeared in newspapers, a deficit of information prevents the creation of a portrait of the "typical victim" (De Wet, 2009:60-64). Snyman (2007) conducted a content analysis on crime reporting in three Gauteng daily newspapers. She found that while the newspapers did make their readers aware of violent crimes taking place, the three newspapers each portrayed only a fraction (and a different fraction) of the reality of crime in South Africa. She found that each newspaper presented a [distorted] view of reality to match the perceived worldviews of its target readers. Snyman (2007) concludes that newspapers make certain assumptions about the type of reporting that their readers want to read, and report accordingly.

In a study on newspaper coverage of the xenophobic attacks during May 2008 in South Africa, Coplan (2009:64-83) found that while local journalists tried to report on these incidences in a responsible manner, "urging an end to violence", they too readily accepted "the most obvious social and 'pop' psychology glosses as necessary and sufficient explanations". Coplan (2009:64-83) warns that by using "facile 'explanations' and self-serving denial, concerning both the economic and social realities of life for the majority of South Africans", reporters, as well as the government, create an "imagined South Africa of competing rhetorical discourses" which makes recognition of the true situation impossible. In a comparative analysis study on the media coverage of violent conflict in KZN, analysing a selection of articles from three KZN newspapers, Jones (2005:151-158) found a "significant breakdown in ethical journalism", superficial reporting, racial bias in coverage and a tendency to use police and other reports as the main sources of reporting.

The above findings of a skewed representation of reality resonate with international research on media portrayal of various forms of violence (e.g. Carlyle et al., 2008; Bullock, 2007). These authors claim that the media fail to expose societal problems and support hegemonic structures in society.

Problem statement

School violence is a severe problem in South African schools and this scourge needs to be addressed. Role-players, inter alia, are informed in the media about the problem, and coverage in the media raises awareness about the problem. Whether or not, and how, newspapers cover a problem could make a difference to how the public views the problem and what should be done about it (Bullock, 2007). Concomitantly, it influences whether readers perceive an issue to be an individual problem or a collective problem, and contributes to perceptions regarding who is responsible for dealing with the problem (e.g. society, the legal system, etc.) (Carlyle et al., 2008). Research on media portrayal of various topics, however, suggests that the media coverage could be distorted, but there is a deficit of studies focusing specifically on the portrayal of school violence in the South African print media. If strategies to curb school violence are constructed in tandem with the (mis)information, these efforts can be compromised. In order to explore the way in which the print media inform the public on school violence, I therefore pose the following research question: How is school violence framed in South African newspapers? I specifically aim to explore the dominant frames presented to the public and identify possible missing frames that could distort the public's perception.

Research methodology: Framing analysis

According to Gamson (1989:157), media framing is "a central organizing idea for making sense of relevant events and suggesting what is at issue". Pan and Kosicki (1993) describe framing analysis as a specific technique for content analysis to explain how the media promote certain aspects of a perceived reality. Carlyle et al. (2008:172) comment that:

[t]he efficacy of frames is found in their ability to make certain elements and perspectives more salient, thereby increasing the chances that certain schemas of interpretation will be evoked.

Pan and Kosicki (1993:58) note certain differences between framing analysis and alternative approaches to news texts. They do not consider news texts as "psychological stimuli" of objective meaning, but rather "organized symbolic devices" that will interact with one's memory for the construction of meaning. Framing analysis also acknowledges that frames in news texts, to some extent, depend on the readers of the texts. Framing goes beyond the obvious topic of a news article by looking at the themes that serve as central organising ideas, as well as how an issue is discussed in the media (Pan & Kosicki, 1993). The aim of framing analysis is to examine the way in which news is framed with the purpose of "audience processing" (Pan & Kosicki, 1993:69), taking into account that the quantity of coverage influences how visible and important the issue appears to be (Bullock, 2007). I employed framing analyses as a method of exploring how newspapers portray school violence in South Africa.

Newspaper articles as data

Document collection was used as a data collection technique (Merriam, 2009). I used newspaper articles as textual data to explore the framing of school violence in South African print newspapers. Newspaper articles are categorised as documents that fall into the category of public records, and are considered important in conveying news that has current interest (Creswell, 2008). Documents offer qualitative data that do not depend on the cooperation of the participants, are not produced for research, and are not affected by the presence of the researcher (Merriam, 2009:139). Documents that are available electronically furthermore provide data that are accessible to others and are easy to obtain (Merriam, 2009:155). From the SAMedia clipping service of the University of the Free State (http://www.samedia.uovs.ac.za/) I obtained, in electronic format, all the newspaper articles classified as pertaining to [school and violence],1published in the 21 newspapers2 that the services use, during 2009. When retrieving documents electronically, the researcher is no longer the primary instrument for collecting data (Merriam, 2009) and I depended solely on the categorisation of articles by analysts at the clipping service to obtain my initial set of 134 newspaper clippings.

While many researchers use documents as secondary sources, in this paper media articles form the core of the research question (cf. Merriam, 2009). I do not use the media articles as secondary sources to gain insight into actual occurrences, but rather as primary voices informing the public and thus shaping public perceptions.

From the documents obtained, I used criterion sampling as a sampling technique (cf. Nieuwenhuys, 2007). Focusing on journalists' reporting as my criterion in view of the purpose of the research, I scrutinised the 134 articles, considering each for its suitability. Only clippings from public newspapers were included, so I removed articles in the sample that appeared in publications of churches and other organisations (e.g. Die Kerkbode and Servamus). In addition, I removed columnists' points of view, as well as editorials and letters from readers. I was then left with a total of 92 distinct articles (not duplicate articles that appeared in different newspapers of the same newsgroup) from 21 public newspapers as my sample.

Using newspapers as data, specific issues pertaining to the integrity of the research emerged, and are discussed below.

The integrity of the research

I took a number of steps towards increasing the integrity of the research. I consider the documents used as authentic (cf. Merriam, 2009) because the cutting service provides a scanned-in, unedited version of the original newspaper clipping, the name of the newspaper, publication date, and the page on which the article appeared. Informed by the focus of the paper, I followed the example set in similar papers by inter alia Bullock (2007) and Welch, Fenwick and Roberts (1998) by listing the newspapers from which the cutting service provided the set of articles. By accessing the website address of SAMedia and the words used in the electronic search, I believe I have left an audit trail. I lastly used an external auditor (cf. Creswell, 2008), namely, an experienced critical reader, to review the paper at various stages. As triangulation of data and member checking are not applicable to this study, I consider the external auditing an effective strategy to address the issue of validity and credibility.

Data analysis

This paper is based on a framing analysis; a specific method of analysing media documents. Issues pertaining to frames in news reporting can include the frequency of coverage, labelling, information included and omitted, and episodic or thematic focus (Bullock, 2007). In line with the guidelines given by Merriam (2009:152) that the point of departure for analysing documents is to "adopt some system of coding and cataloguing them", I carefully read through each article with the aim of coding the primary news frame as episodic or thematic. I furthermore coded the sources that the reporters used, the suggested solutions, the types of violence and contextual information provided (cf. Bullock, 2007; McManus & Dorfman, 2001). I repeated this process with a second set of prints of the articles, and compared the two sets of coding. I captured all coding and keywords in an Excel file.

Based on the coding, I portray media framing in terms of frequency of reporting. Frequency tables provide information on the number of times newspapers report on a specific issue, using specific information, during a certain time period. When considering the number of articles purporting a specific frame, one needs to keep in mind that the frequency of framing should not be equated with the actual frequency of the occurrence of violence. In some cases, only one article described an incident, while in other cases, the same incident was reported repeatedly, sometimes in the same newspaper, but also in various other newspapers. The frequency tables that follow thus present the frequency of frames presented in the selected sample of newspapers. The frequency of frames matters, as it shapes the perceptions of the readers concerning the importance of an issue.

I have converted the frequencies into a percentage format to ensure easy comparisons. One should, however, be mindful that some articles focused on campaigns and not on incidences of violence, whereas others reported on more than one incident; therefore the figures do not add up to 100%. I provided percentages to relativise the figures. The analyses rendered the findings that follow.

Results

Episodic versus thematic coverage

Episodic coverage focuses on personal tragedies isolated from the social context, using explanations about individual personalities. Thematic coverage focuses, in addition to the individual aspects, on the wider circumstances and the role of society. While the former promotes indifference and civic powerlessness, the latter draws social or political response (Carlyle et al., 2008; McManus & Dorfman, 2001).

I found that 75% of the articles in the sample were episodic reporting, in other words, merely reporting on what happened, without placing the incident within the larger societal picture. The 17 articles that focused solely on campaigns, by bodies such as the Department of Basic Education (DBE), the South African Police Services (SAPS) and others, in order to reduce the levels of violence in South African schools, showed a smaller proportion of episodic coverage (eight) compared to thematic coverage (nine), which constitutes a ratio of 47:53. In contrast, the 75 articles that reported on incidences of school violence used 61 episodic frames compared to only 14 articles that used thematic frames, which is a ratio of 81:19.

Who gets to speak to the public?

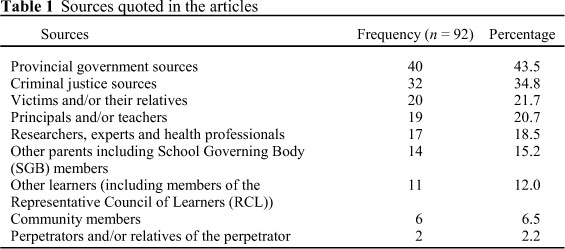

Reporting on school violence is dominated by references to government officials, such as Members of Executive Councils (MECs) and DBE spokespersons (43.5%). The second most frequently quoted sources come from the criminal justice system, such as members of the SAPS, court officials, and court proceedings (30.4%). In only one article the perpetrator is used as a source and, likewise, in only one article a relative of the perpetrator is used as a source. Further details are supplied in Table 1.

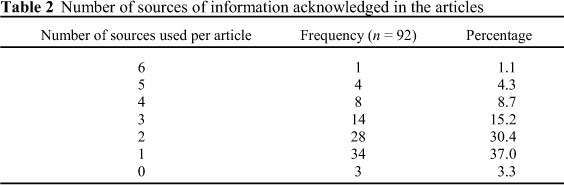

The majority of the articles were, furthermore, based on only one or two sources (67.4%), while articles based on more than four sources were scarce (5.4%). In three (3.3%) articles the source was not identifiable. Further details follow in Table 2.

The single article that used six different categories of sources used a parent of the victim and the victim herself, other parents, other learners, an SAPS official, a hospital spokesperson, as well as court proceedings to obtain information. Likewise, one of only two articles that used five different categories of sources used the victim, teachers, other learners, a DBE spokesperson and an SAPS spokesperson. These few journalists attempted to portray incidences of violence from various perspectives, even if they did not exhaust their options.

Solution frames

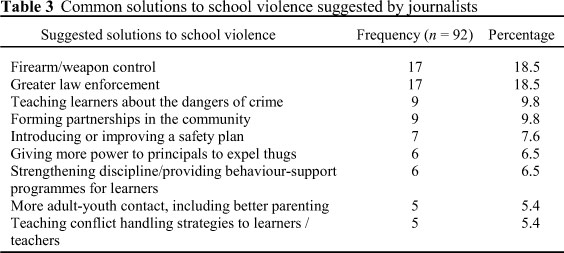

Solution frames suggest some form of cure for a problem and send out a message to the public that something can be done to improve the situation (McManus & Dorfman, 2001:17). However, in 42.4% of the articles in my sample, no solution was offered to the problem of school violence. A wide variety of solutions was indicated in the rest of the articles, the most popular solutions being listed in Table 3.

The two most common solutions put forward in the articles, namely, firearm and weapon control (18.5%) and greater law enforcement (18.5%) both suggest that school violence is a criminal justice problem.

The types of violence

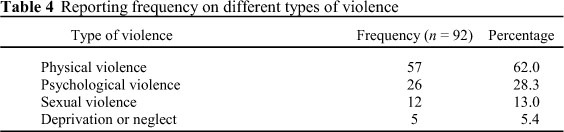

I looked at what is regarded as newsworthy types of school violence. Details of this reporting are given in Table 4.

Incidences of physical violence, which ranged from shoving and fighting to lethal stabbings and shootings, were reported in 62% of the articles. Deprivation, categorised as school violence, received the least attention in these articles (5.4%). None of the articles focused specifically on deprivation, neglect or psychological violence, but merely discussed these as part of reports focusing on physical violence. Only two articles reported solely on sexual violence, but both the articles dealt with the same incident in which a girl was gang-raped in a school dormitory by outsiders - an indisputably severe physical and sexual act of violence. In the other 10 articles that reported sexual violence, the focus was, once again, on physical violence.

Contextual frames

Contextual frames are important for the way in which news is framed, as they can strengthen or weaken society's perception of the culpability of its environment regarding school violence (McManus & Dorfman, 2001). These frames further contribute to stereotypical perceptions of dangerous schools. I looked at the provincial frames, the school type frames and the weapon frames, as these were recurrent contextual factors that dominated in the sample of articles I selected.

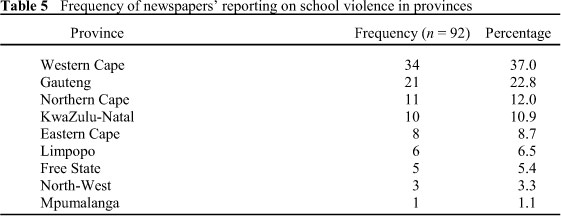

Provincial frames

Reporting on school violence in the various provinces varies in frequency, as can be seen in Table 5. One cannot assume that incidences of school violence that occur in a specific province will always only be reported in newspapers distributed in that province. I found it was not the case.

Newspapers reported on incidences of school violence which occurred in the Western Cape more often than on incidences in any other province (37%), while Mpumalanga was referred to in only one article.

School type

Reporting focused mainly on incidences of school violence that occurred at secondary schools, while only one article reported on violence in a pre-primary school. Specific references to other school types were also made. It should be noted that the categories in Table 6 are not mutually exclusive.

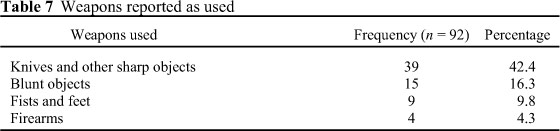

Frames on weapons used

The weapons that are most frequently reported as used in incidences of school violence are knives and other sharp objects (42.4%). Not all articles reported the weapon used and firearms were mentioned in only four articles (4.3%) (see Table 7).

Discussion

Findings

In this study I explored the dominant frames put forward in the media when reporting on school violence in South Africa. Journalists seem, when reporting on campaigns against school violence, to be more prone to portray school violence as a societal problem but, when reporting on incidences of school violence, the portrayal moves to frames that ignore societal factors. The dominance of episodic coverage is in line with findings in other framing analyses (cf. Carlyle et al., 2008; McManus & Dorfman, 2001). Maxwell et al. (in Carlyle et al., 2008:173) state that, by doing this, the media shift the responsibility of solving the problem from society to the individual [for instance the school, or the parent of the perpetrator]. Reporting on school violence seems to be dominated by official sources such as DBE members, district officials and other provincial officers, together with members of the SAPS, and court officials. Furthermore, the majority of journalists appear to consider the views of the perpetrators and their relatives, as well as those of community members, as irrelevant when reporting on school violence. This, in my view, represents a disproportionate voice.

In many articles no solution to the problem is suggested. McManus and Dorfman (2001:23) claim that the sense of there being little need for the explanation of solutions suggests that the public already understands [school] violence and, therefore, there is no need to stimulate thinking about "what can be done". In the articles that did present some solutions, the two most common solutions, namely, firearm and weapon control, as well as greater law enforcement, both suggest that school violence is a criminal justice problem. This, in my view, strengthens the perception that society is powerless regarding the prevention of school violence and that it is simply a "law and order" problem (cf. Bullock, 2007:52).

Media coverage focuses mainly on physical violence. As such, newspapers are gradually convincing the public that school violence equates to physical violence (Carlyle et al., 2008). Studies comparing levels of the different types of school violence, however, suggest that although physical violence is indeed a problem in South African schools, other types of violence are an equal problem, if not more so (for example, De Wet, 2007; Prinsloo & Neser, 2007). These studies suggest furthermore that seemingly less sensational physical violence is more common in schools than the fierce acts which are reported in newspapers. While reporting on psychological violence, sexual violence, and deprivation may have occurred during the year from which the sample of articles was drawn, it was clearly not strongly framed as school violence and, therefore, was not identified as such by the clipping service I used. The possibility, however, also exists that reporting did not take place because these crimes were not considered to be sufficiently newsworthy. Whichever is true (and I suspect both to be true to some extent), such framing strengthens the conceptualisation of school violence as having a physical dimension only, and fails to acknowledge other forms of violence, in spite of the severity of their effect. This has implications in terms of social awareness, and how society should respond (cf. Carlyle et al., 2008).

Specific perceptions regarding contexts that generate school violence are created. School violence is specifically framed as an issue that occurs mainly at Western Cape secondary schools, where knives and sharp objects are used by the learners.

In line with the second objective of the study, I find it essential to reflect briefly on frames that I found lacking in the sample of newspaper articles. The costs of school violence rarely appear, and where they do, only the cost of setting up security systems for schools is mentioned (but no figures are provided). Medical costs, police costs and court costs are, for example, are not mentioned at all. Ethnic descriptions are omitted in all cases. The words 'racial violence' and 'racism' are used in some articles, however, without giving any further details. This lack of information could result in readers falling back on default frames of racial stereotypes that exist in South African society. On the other hand, in a study in California, USA, on the frames portraying youth violence, the race of perpetrators was mentioned in 39% of the articles that were studied (McManus & Dorfman, 2001:20).

While some weapons were reported on, none of the newspaper articles mentioned how learners obtained the weapons. The public is rarely informed about the long-term effects of school violence incidences on the people involved. I also found that there is a lack of follow-up articles on incidences of violence, while the outcomes of the judicial proceedings of school violence receive little attention. Although drug abuse and alcohol abuse are mentioned in a small number of articles, I did not find a strong enough frame to elicit a reaction from society to do something about the easy access that learners have to these substances. In an USA study, this was also the case, and McManus and Dorfman (2001:24) state that such reporting has "far less chance to make an impression on public consciousness".

While considering the insights that I gained during the analyses done in this study, I also needed to reflect on the strengths and limitations thereof.

Strengths and limitations

The first limitation that should be noted is the sole use of newspaper articles. I suggest that follow-up research on news media portrayals of school violence could consider the portrayal of school violence on radio, television, and in popular magazines. The second limitation came from using only two words, [school] and [violence] to search the SAMedia database. In retrospect, I believe I could have expanded the search by using various other key words to include specific acts; for instance [school and rape], [school and bullying] and [school and assault].

In spite of the limitations mentioned above, this paper hopefully provides a fresh method in terms of education research, and specifically, research on school violence. Framing analysis, as a research method, is still developing and many interpretationsexist (Shaw & Giles, 2009). Other studies could build on this one, possibly exploring alternative framing structures. Although the media provided only partial information, I gained insight into perspectives that I would otherwise not have obtained. No researcher can immediately go to where incidences of school violence have occurred and gain access to the sources; therefore, such media-data is valuable. Furthermore, I believe that this paper provides unusual insight into the information on school violence that newspapers make available to the public. People use this, and other information, to make sense of school violence.

Conclusion and recommendations

School violence is complex and has many facets, some of which are difficult to see. Newspapers give school violence unbalanced coverage and, in this way, fail to inform and make the public aware of this danger to society. The main frames provided to readers in South African newspapers largely fail to elicit social responsibility, while at the same time, promote civic indifference.

I therefore suggest that schools should make role-players aware of the many facets of school violence. In addition, I recommend that schools collaborate with the media so that authentic information can be provided via the schools to the public, and reporters can have access to information from the schools. Striving towards creating positive learning environments in schools requires inter alia the support of a well-informed public. The mass media therefore has a responsibility to inform society comprehensively, accurately, and impartially on violence in South African schools.

Notes

1 The electronic service allows for only two search words and I used 'school' and 'violence'. The 'and' indicates that both these words need to be in the classification.

2 Beeld, Burger, Cape Argus, Cape Times, Citizen, City Press, Daily Dispatch, Daily News, Diamond Fields Advertiser, Pretoria News, Saturday Argus, Saturday Star, Sowetan, Star, Sunday Argus, Sunday Times, Sunday Tribune, The Herald (EP Herald), The Times, Volksblad, Witness.

References

Bullock CF 2007. Framing domestic violence fatalities: Coverage by Utah newspapers. Women's Studies in Communication, 30(1):34-63. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2007.10162504 [ Links ]

Business Day 2006. Principals have right to search pupils. [ Links ]

Carlyle KE, Slater MD & Chakroff JL 2008. Newspaper coverage of intimate partner violence: skewing representations of risk. Journal of Communication, 58(1):168-186. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00379.x [ Links ]

Carstens S 2006. Menseregte 'stu geweld in skole'. Rapport, 23 Julie. Available at http://152.111.1.87/argief/berigte/rapport/2006/07/23/R1/6/02.html. Accessed 6 December 2013. [ Links ]

Coplan DB 2009. Innocent violence: social exclusion, identity, and the press in an African democracy. Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies, 23(1):64-83. doi: 10.1080/02560040902738982 [ Links ]

Creswell JW 2008. Educational research: planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. [ Links ]

Davids N & Makwabe B 2007. Our children are raping each other. Sunday Times, 18 November. [ Links ]

De Wet NC 2003a. Skoolveiligheid en misdaadbekamping: die sieninge van 'n groep Vrystaatse leerders en opvoeders. South African Journal of Education, 23(2):85-93. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/educat/educat_v23_n2_a1.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2013. [ Links ]

De Wet NC 2003b. 'n Media-analise oor misdaad in die Suid-Afrikaanse onderwys. South African Journal of Education, 23(1):36-44. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/educat/educat_v23_n1_a7.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2013. [ Links ]

De Wet NC 2005. The nature and extent of bullying in Free State secondary schools. South African Journal of Education, 25(2):82-88. [ Links ]

De Wet C 2007. Educators' perception and observation of learner-on-learner violence and violence-related behaviour. African Education Review, 4(2):75-93. doi: 10.1080/18146620701652713 [ Links ]

De Wet NC 2009. Newspapers' portrayal of school violence in South Africa. Acta Criminologica, 22(1):46-67. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/crim/crim_v22_n1_a6.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2013. [ Links ]

De Wet NC & Jacobs L 2009. A comparison between boys' and girls' experience of peer sexual harassment. Journal for Christian Scholarship, 45(3):55-75. [ Links ]

De Wet NC, Jacobs L & Palm-Forster TI 2008. Sexual harassment in Free State Schools: An exploratory study. Acta Criminologica, 21(1):97-122. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/crim/crim_v21_n1_a9.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2013. [ Links ]

Fitzpatrick M 2006. SA skole: 'n ramp. Huisgenoot, 25 Oktober. [ Links ]

Fredericks I & Mposa N 2012. Shock over pupil's fatal stabbing. Cape Argus, 29 February. Available at http://www.iol.co.za/capeargus/shock-over-pupil-s-fatal-stabbing-1.1245503. Accessed 2 March 2012. [ Links ]

Gamson WA 1989. News as framing: Comment on Graber. American Behavioral Scientist, 33(2):157-161. [ Links ]

Govender P 2009. Principal kicked me repeatedly. The Times, 9 May. [ Links ]

Hadebe G 2000. Smart schools achieve excellence. Proceedings of the first educationally speaking conference. Johannesburg: Gauteng Department of Education. [ Links ]

Henry S 2000. What is school violence? An integrated definition. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 567(1):16-29. DOI:10.1177/ 000271620056700102 [ Links ]

Jacobs L 2012. School violence: A multidimensional educational nemesis. Unpublished PhD thesis. Bloemfontein: University of the Free State. Available at http://etd.uovs.ac.za/ETD-db/theses/available/etd-08212012-155455/unrestricted/JacobsL.pdf. Accessed 6 December 2013. [ Links ]

Jones NJ 2005. News values, ethics and violence in KwaZulu-Natal: has media coverage reformed? Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies, 19(1 &2):150-166. doi: 10.1080/02560040585310101 [ Links ]

Kgobe P & Mbokazi S 2008. The impact of school and community partnerships on addressing violence in schools. In C Malcolm, E Motala, S Motala, G Moyo, J Pampallis & B Thaver (eds). Democracy, Human Rights and Social Justice in Education. Johannesburg: Centre for Education Policy Development (CEPD). Available at http://www.cepd.org.za/files/CEPD_EPC_conference_proceedrngs_2007.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2013. [ Links ]

Krug GK, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL & Zwi AB 2002. The world report on violence and health. Lancet, 360 (9339):1083-1088. [ Links ]

Maphumulo S 2010. Gauteng's school of shame. Star, 15 September. Available at http://m.iol.co.za/article/view/s/11/a/22017. Accessed 9 December 2013. [ Links ]

Marais P & Meier C 2010. Disruptive behaviour in the Foundation Phase of schooling. South African Journal of Education, 30(1):41-57. Available at http://www.scielo.org.za/pdf/saje/v30n1/v30n1a04.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2013. [ Links ]

Masitsa MG 2011. Exploring safety in township secondary schools in the Free State province. South African Journal of Education, 31(2):163-174. Available at http://www.sajournalofeducation.co.za/index.php/saje/article/view/477/245. Accessed 9 December 2013. [ Links ]

McManus J & Dorfman L 2001. Framing youth violence. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (84th, Washington, DC, 5-8 August). [ Links ]

Merriam SB 2009. Qualitative research. A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [ Links ]

Nieuwenhuys J 2007. Qualitative research designs and data gathering techniques. In K Maree (ed). First Steps in Research. Pretoria: Van Schaik. [ Links ]

Oosthuizen IJ & De Waal E 2005. Orientation to safe schools. In IJ Oosthuizen (ed). Safe Schools. Pretoria: Centre for Education Law and Policy (CELP). [ Links ]

Pan Z & Kosicki G 1993. Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication, 10(1):55-75. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963 [ Links ]

Prinsloo IJ 2005. How safe are South African schools? South African Journal of Education, 25(1):5-10. Available at http://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/4188/Prinsloo_How%282005%29.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed 9 December 2013. [ Links ]

Prinsloo J & Neser J 2007. Operational assessment areas of verbal, physical and relational peer victimisation in relation to the prevention of school violence in public schools in Tswane South. Acta Criminologica, 20(3):46-60. Available at http://reference.sabinet.co.za/webx/access/electronic_journals/crim/crim_v20_n3_a5.pdf. Accessed 9 December 2013. [ Links ]

Republic of South Africa (RSA) 1996. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996). Pretoria: Government Printers. [ Links ]

Seale L 2008. Another pupil stabbed at school. Star, 11 September. Available at http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/another-pupil-stabbed-at-school-1.416046#.UqheRyfWj1U. Accessed 11 December 2013. [ Links ]

Shaw RL & Giles DC 2009. Motherhood on ice? A media framing analysis of older mothers in the UK news. Psychology and Health, 24(2):221-236. doi:10.1080/08870440701601625 [ Links ]

Snyman ME 2007. Misdaadberiggewing in die pers: 'n weerspieeling van die werklikheid. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe, 47(4):103-118. [ Links ]

Welch M, Fenwick M & Roberts M 1998. State managers, intellectuals and the media: A content analysis of ideology in experts' quotes in feature newspaper articles on crime. Justice Quarterly, 15(2):219-241. doi: 10.1080/07418829800093721 [ Links ]