Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Journal of Gender and Religion

versão On-line ISSN 2707-2991

AJGR vol.29 no.1 Johannesburg 2023

ARTICLES

[In] Searching Our Mothers' Archives: Building Umi's Archive through Mourning Work

Su'ad Abdul Khabeer

University of Michigan drsuad@umich.edu https://orcid.org/0009-0009-0857-1792

ABSTRACT

Black feminist scholarship provokes us to reimagine archives in creative and speculative ways and echoes everyday Black communities' deep investment in memory that rejects the idea of African people as a people without history. I enter this discourse through Umi's Archive is an interdisciplinary and multimedia research project that draws on my family archive to engage everyday Black women's thought to investigate key questions of archives and power. In this article, I describe my experience curating, preserving, and presenting the archive and how that became a process of de-disciplining myself, turning to intimacy and mourning to learn from Black women by searching in my Umi's archive.

Keywords: Archive, intimacy, mourning

Introduction

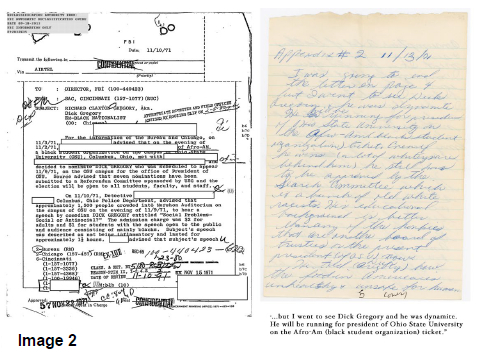

In November 1971, Dick Gregory visited the Ohio State University (OSU) at the invitation of the student group, Afro-Am. In a letter written by my mother, then Audrey, to her childhood friend, Violet, she describes the Black US American comedian and activist's visit.

I was going to end the letter on page 4 but I went to see Dick Gregory & he was dynamite. He will be running for president of Ohio State University on the Afro-Am ticket. Even if he wins (a lot of whiteys are behind him) he still has to be approved by the search committee which is a bunch of old white racists. His educational background is better than any of the honkies that are on the board of trustees or the present president (of O.S.U) now. He told (Dick Gregory) how the food in America is unhealthy and unsafe for human consumption. A lot of brothers and sisters are giving up meat. It is bad for you. I'm going to start reading some books about it before I preach too much. I heard once I finish reading, I won't want to eat nothing. Right now I plan on cutting down my meat & try to eat 1 1/2 meals a day instead of 4 meals a day (smile)... He also rapped about the war (He was 288 lbs and now he weighs less than 100lbs.). He is still fasting (only drinks fruit juices & water). Since he doesn't shit any more he says he'll still sit on the toilet & pretend he's shitting because he says people do the heaviest thinking when they're on the toilet (smile). He said white folks & black folks should organize a boycott of Thanksgiving (to stop buying turkeys) & or Christmas (to stop buying presents) in protest of the war. Once you hit the pocketbooks of those fat wealthy crackers, you hit the real power of the U.S. He said if you stop buying General Motors products you could paralyze the country & that the chairman of the board of G.M. would personally wake up tricky Dicky & tell him to stop the war! The whiteys can do it but Violet we know that they aren't into doing shit. They where (sic) long hair & talk about love & peace but when it comes to action they're full of it. Maybe they'll surprise us!

The letter goes on to discuss the Black Panther Party (BPP) Communications Secretary, Kathleen Cleaver's, visit to OSU. It also enumerates the crimes of the US that Audrey describes as the "most racist, despotic, slick, sly, degenerate system in the world". These crimes are imperial, propping up puppet governments in the Congo and the Korean Peninsula, and national, she writes: "bs drug and prison reform, no one in the mafia is going to jail for drugs just our brother and sisters". The letter ends, exhorting Violet to raise her daughter as a revolutionary and closes with:

Well I better stop writing. Don't you think I should (smile) I hope you

can understand my

handwriting (hieroglyphics) Well tell everyone I said hello & tell me

what they're doing

(Lawrence, Joanne, Melvin, rocky, Nancy, Erika, Diane).

Keep on keeping on.

Power to the People. Blk Power to Black People

Love, Audrey

P.S. Survival is a bitch!

My mother, Amina Amatul Haqq, was born Audrey Beatrice Weeks in 1950 in Harlem, New York. Her parents, Aubrey J. Weeks and Carmen M. Inniss Weeks, were also born in Harlem but were the children of immigrants to the United States from the then British colonies of Montserrat and Barbados, respectively. After serving in World War II, her father secured a rare position as a fireman and, as result, the family left an apartment in Harlem for a single-family home in Queens in 1953. Unlike her parents, my mother was university-bound, but not to the historically-Black college she wanted to go to but, instead, to the predominately white institution of OSU. She ended up at OSU in 1968 because my grandmother feared her outspoken daughter would be killed if she went "down south". Ironically, going to OSU did not keep her out of trouble.

And if you go to the seventies, I was...embarking on a political journey. I was a member of the African Liberation Support Committee, Pan African Congress, Black Panther Party...the All African Liberation Support Committee... I got into my culture...when I went to Ohio State, we brought African dance to Columbus, Ohio. And I organized this group called the Uhuru Dancers - a hundred pounds ago...We shut the school down in 1970...we demonstrated on campus for Black studies. The white kids were against the war in Vietnam. So, we had sort of like a coalition. And I remember when the National Guard came, and this was first time I ever smelled tear gas.

In this interview, recorded a few months before her death, my mother, now Amina, describes her activism from 1968 through to the early 1970s.1 She was active in student organizations that worked to raise political consciousness, were committed to Pan-Africanism, and helped to establish Black Studies at the university. Reading the letter for the first time in 2018 confirmed what I already knew: that her time in college was a key node in a lifetime of activism. I found the above letter, which was never mailed to Violet, among a collection of correspondence that included birthday cards and wedding invitations sent to my mother during the early 1970s. The correspondence was in a broken drawer buried deep in a basement closet of the Queens home. I found it while doing "death cleaning", a Swedish term for sorting through one's things before death, although I was cleaning for those who had already passed on. I was death cleaning because my mother died suddenly in October 2017, five months after the death of her own mother, three days after I had been joking with her and making her rub my head during a visit home to New York to promote my first book, and a few hours after we spoke on the phone about her accompanying me on my next international research trip.

As the oldest of the family's two daughters and granddaughters, the responsibility of death cleaning for my mother and my family fell to me. I cleaned out the bedrooms and basements, file cabinets and bookshelves examining everything from family photos from the 1930s to personal emails to decide what to let go of and what to archive. The archive is a repository of the remarkable nature of my mother's everyday life, like being given her shahadah (testimony of faith) in 1975 by one of Malcolm X's "right hand men", or helping organize an economic boycott in Queens after the NYPD killed a ten-year-old Black boy named Clifford Glover, or protesting apartheid for African Liberation Day in Washington DC in 1972. As I went through her and my family's papers and belongings, I found the stories had much broader implications as Afrodiasporic and Black Atlantic narratives. The archive documents my mother's roots as the granddaughter of Caribbean migrants who came to Harlem in the early 1900s and narrates her experiences as a Black public-school student in the mid-twentieth century Jim and Jane Crow North. They tell stories of her activism as a college student in the Black Power movement as well as stories of faith and Black women's heartaches, seen in her unfulfilled quest to find "my own Malcolm", as she texted to a friend.

Black feminist scholarship provokes us to reimagine archives in creative and speculative ways.2 This work echoes everyday Black communities' deep investment in memory that rejects the idea of African people as a people without history. I enter this discourse through "Umi's Archive", an interdisciplinary and multimedia research project that engages everyday Black women's thought to investigate key questions of archives and power, particularly asking what new knowledges arise from narrating stories that, officially, do not matter? Umi's Archive is a physical archive, cataloguing the personal and familial artifacts of the NYC based Black Muslim woman community activist, Amina Amatul Haqq, whom I called umi (Black Arabic for "mommy"). It is also a digital space as an exhibition series found at umisarchive.com. Umi's Archive is a generative, analytical space that examines the many facets of being Black and, most importantly, I offer it as an imaginative space where we remember the past so we can dream up the future we want.

The title of this essay is a riff off Alice Walker's essay "In Search of Our Mothers Gardens" where Walker uses the garden as a metaphor for the generations of Black women that preceded her, who, due to slavery and racialized gender oppression, could not be artists and thinkers and so invested their creative energies into other spaces, like gardens. For Walker, the task of her generation was to recover and fill in the silences for their mothers and grandmothers. I swap gardens for archives because what I narrate is a different, though related, relation to the past. Building on the liberatory impulses and struggles they inherited, Walker and my mother's generation did important work of recovery, reclamation, and preservation. Accordingly, my work is not to fill the silences but to listen to their voices toward building for the future. I also invoke the term because it has a gravitas that is worthy of the history she saved and preserved, without official license, as a fugitive practice.3 A practice whose fugitivity, considering ramped up efforts to erase the past, is more critical than ever. In what remains, I walk through what happens when I am in the archive, after I found the letter, and the kind de-disciplining I learned by searching my mother's archive.

Citations + Canon + Archival Authority

My mother's reference to Gregory piqued my interest and made me laugh out loud - asé to Dick Gregory who is hilarious in the third person and 40 years after the fact. I decided to search online to see if I might find a newspaper clipping about Gregory's visit. I anticipated getting a hit or two that I would have to delve deeper into. However, the first relevant result was not from a news organization but, instead, an almost 500-page Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) file on Gregory. Gregory had visited OSU a few times, including the visit my mother writes about and, by that time, had been under FBI surveillance for four years under J. Edgar Hoover's Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO). COINTELPRO targeted groups the state considered a danger to national security, which included organizations such as the communist party, Students for Democratic Society, the BPP, The Nation of Islam, and individuals like Martin Luther King, Jr., and Dick Gregory. Hoover's interest in Gregory, who he considered to be a militant Black nationalist, led him to direct FBI agents to develop "a counterintelligence operation to alert the mafia organization, La Costa Nostra (LCN), to Gregory's attack on the LCN" to "neutralize" him.4 With respect to Black nationalist and radical groups, COINTELPRO established special agents in 41 cities, including Cincinnati where the report on Gregory to the FBI was sent.

The confidential report, released with redactions under the Freedom of Information Act, indicates either an undercover agent or a paid local informant conducted surveillance of Gregory and the student group, Afro-Am, in coordination with local Columbus law enforcement and OSU campus security. As I read the clandestine report, I was struck by the points of correspondence and dissonance in Audrey's and the FBI's accounts. Both speak to Gregory's weight loss, his comments on Thanksgiving and General Motors, and his suggestion for an economic boycott. However, where Audrey wrote Dick Gregory "said white folks & black folks" should boycott, the FBI reports that "subject indicated that...war profiteers would be more apt to pressure the establishment if their profits were adversely affected by a black boycott". Considering that a multiracial call to boycott was more in line with Gregory's politics and, frankly, a more effective political strategy, the FBI's claim that Gregory advocated for a Black-only boycott is telling.

I found another correspondence/dissonance particularly chilling. Audrey writes that Afro-Am nominated Dick Gregory to run for president of OSU, but does not describe being at the nomination meeting, in contrast to the FBI: "[Redacted name] advised that on the evening of 11/2/71 [Redacted names] of Afro-Am, a black student organization on the campus of OSU met with [Redacted names] and decided to nominate Dick Gregory". Notably, when researching Afro-Am, I found an article in the official, student-run university paper, The Lantern, that negatively reported on Afro-Am's decision to keep all student meetings private even from the local student press.5 This archival juxtaposition reiterates what we now know about FBI surveillance of the period in which, through a series of techniques including phone taps, informants and agent provocateurs, anonymous letters, and incendiary publications, the US government sought to inspire chaos and disunity within and between Black Nationalist organizations.6 Furthermore, considering recent disclosures of contemporary surveillance of "Black Identity Extremists" and Muslims, this archival find demonstrates the historical continuity of state repression.7 However what I focus on here is what this juxtaposition revealed to me about the question of citations, archival authority, and who gets to be a knowledge producer.

When, honestly, retracing my steps, I realized that I initially looked for a newspaper clipping on the impulse to verify or corroborate my mother's account. This impulse exceeded what I see to be a general instinct, from scholarship to gossip, to gather evidence to double-check new information. Rather, I moved to corroborate because my scholarly training had taught me that the account of a young, unknown (to some) Black woman student, would not be considered authoritative on its own, quite unlike how the FBI, despite a legacy of documented unreliability even by the agency's own admissions, is still considered an authority. Black women are objects of study, objects of desire, and objects of consumption, but are rarely considered as intellectuals, people who think and whose thoughts of epistemic significance. Yet when reading the FBI report in comparison to her own account, my interest was no longer in verifying her account but providing accuracy to the archive itself that then turned into a motivation not to verify as much as rectify, which later became something altogether distinct.

Recovery has long been the aim of Black memory-work that scholars locate as first emerging as "an abolitionist tool in the nineteenth century" Black Atlantic.8 Critically, Black memory-work continues to be an everyday and scholarly endeavor as Black Study continues to have political urgency. Yet, this tradition of recovery and vindication is in tension with contemporary scholarship that questions if recovery is even possible and if recovery will reproduce the systems it means to challenge. In her oft-cited essay, Hartman, upon uncovering the name of a black girl murdered on a slave ship, concludes "my account replicates the very order of violence that it writes against by placing yet another demand upon the girl, by requiring that her life be made useful or instructive, by finding in it a lesson for our future or a hope for history".9 /

McKittrick, engaging Hartman, also notes the ways we pull Black history from

"documents, ledgers and logs" and asks when,

the death toll becomes the source...how then do we think and write foster a commitment to acknowledging violence and undoing it's persistent frame, rather than simply analytically reprising violence?10

Relatedly, David Scott critiques what he calls "a narrative of continuities" that defines the anthropological approach to the African diaspora, focused on African retentions in order to prove Black humanity.11 According to Scott, this leads to seeking to endow Black people with an "authentic past, that is anthropologically identifiable, ethnologically recoverable and textually re-presentable".12 Yet, by creating a past that makes sense anthropologically, we end up reproducing colonial logic through a quest for "referential accuracy".13

References become citations and citations build canons and canons, like cannons, are weapons that preserve and take lives. Accordingly, Ahmed identifies citational practice as a progenitive technology that "reproduces the world around certain bodies".14 In this context, I came to understand the call to "Cite Black Women" more expansively. The call turned campaign, led by anthropologist Christen Smith, exhorts "people to engage in a radical praxis of citation that acknowledges and honors Black women's transnational intellectual production"15 This call to recognize Black women as epistemic resources, as producers of knowledge, is a call to reject and upend the colonial logics that undergirds the canon - the body of work that defines what counts as knowledge and worth knowing. It vitally interrupts the ways our scholarly work, with all its "liberal" tendencies, operates in concert with violence, both within and beyond the academy, that targets Black women's lives and thoughts, for death.

Returning to Audrey's letter with a perspective more grounded in these decolonizing theorizations, I recognize the FBI's account as not only dubious but a mid-twentieth century bureaucratic rendering of the old fear of the African danger to the colony. Furthermore, I am no longer seeking to verify what Audrey/Amina/Umi said but, rather, I cite a Black woman and take her account seriously as an authoritative, and still fallible, source of knowledge. Building on Clyde Wood's classic history, Development Arrested, Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues we should approach "archives as proposals rather than proofs" and that "proposals are evidence of struggle".16 Evidence that, as Yusuf Omowale reminds us, "we have always been present." (Omowale: 2018).17 Thus, my analysis of Audrey's letter ultimately moved me away from colonial logics that demand we "verify" a Black past and toward practices of listening, reading, and creative speculation that build new archives that propose new possibilities.

Curating, Preserving and Presenting the Archive

Finding artifacts, like this letter, motivated another impulse: to share. I immediately knew there were people, even outside my mother's networks, who would see themselves in the archive, learn from it, and be moved to act because of it. Accordingly, I wanted to make her collection open to the public. However, before I could do so, I had to complete some key tasks: deciding what to keep, learning how to preserve and then managing curation, and what it would mean to represent the archive to others.

Deciding what to keep was my first task as a memory-worker/death cleaner and was guided by memory. Certain items, like the letter to Violet, would spark a memory. In this case, it was Umi's stories about her political radicalism in college. The item might carry details that provide greater historical context and its tone and texture can bring those stories to life. Some items would also teach me new things, such as the FBI's surveillance of Gregory and Black Students at OSU, as would seeing items in relation to each other. In my mother's 1968 high school yearbook, one classmate's autograph message calls her a "stone black woman" whose dancing "makes you think" while another, white, classmate's autograph chides her that she would get more bees with honey than vinegar. Her Black consciousness is also mapped on her college transcripts. As a student she took multiple years of Swahili, the Black Studies courses she fought for, and a marksmanship course, underscoring how serious she was about her political commitments.

This task of deciding what to keep was also driven by my mother's archival practice. She was not formally trained in archival methods but did intentionally preserve objects, thereby giving them significance, what Ewing terms as "fugitive archival practice".18 Fugitive archives are the domestic collections found in Black US American communities, curated through the preservation practices often mislabeled as hoarding, of Black women who grew up during the Great Depression through to the Baby Boom.19 Ewing argues that "their experiences with racism, erasure from public records, and difficulties with homeownership" impressed upon them the importance of preservation, while barring them from the means or access to formal preservation schemes, thus, making theirs a fugitive practice.20 I would not say my mother was a hoarder, but it often felt like there was too much stuff in too little space. We often bickered playfully during my visits home when I would encourage her to get rid of "stuff". She knew more than I how significant her "stuff' was and I remain grateful she "paid me no mind".

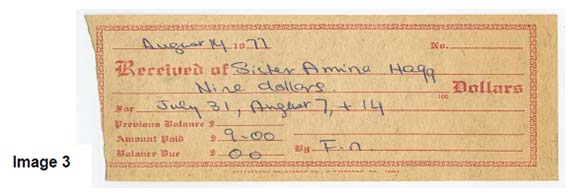

Take, for example, receipts. Umi had become her mother's legal guardian and as a result, had to submit a yearly accounting to the local court, demonstrating she was not misusing her mother's savings. Accordingly, she would save receipts from purchases she made for my grandmother. I found these receipts in all sorts of places, typically held together by a paper clip and stored in an envelope that had come as mail but now served as a kind of file folder. She saved these receipts that tell a story about class, race, and bureaucracy, but she did not preserve them. The receipts were haphazardly collected and some had faded despite only being a few years old. They were in a different state than another receipt in the archive. This receipt was for an Arabic language course Amina took in the summer of 1977 that is in such pristine condition it looks as if it was only written yesterday. That receipt was stored in a folder that was kept in bookshelf cupboard with related materials from the period when she was a new Muslim. While both kinds of receipts have significance, paying attention to how she preserved things helped me understand what was significant to her and, thus, what I should keep.21

After deciding what to keep, I also needed to think about preservation. Like my mother, I do not have formal archival training but, unlike my mother, I do have a tenure track position at a research university that gives me access to those with that expertise. After following my friend, colleague, and oral historian, Zaheer Ali's, lead (he first impressed upon me the importance of preservation), I went to the librarians at my university who helped me further evaluate my needs, including appropriate storage materials from high-end to lower-end hacks that I purchased based on the latitude of my research and personal budgets. I also hired research assistants who learned with me and taught me about how to organize materials, create metadata, and a finding aid for the archival materials that are currently in about 30 archival boxes in a spare closet in my university office suite.22

Now I faced the task of managing both curation and representation. Another good friend and artist, Leslie Hewitt, played a key role in my thinking about presenting the archive to the public. She encouraged me to think about the artifacts in relationship to each other and how the physical representation of that juxtaposition could be an opportunity to not only share the archive but provoke audience thinking. Inspired by her suggestion, I initially planned on producing a one-woman show based on the archive, employing the research-to-performance and performance ethnography methods I had used in previous work.23 That plan was forestalled by COVID, so I pivoted, like everyone, online.

In the spring of 2021, I launched a six-part online exhibition series on the archive.24 Exhibitions were expository and interpretive, exploring themes culled from my analysis: Black Muslim women's spirituality; love and relationships; dance and Black identity; Black Power; and the African Diaspora. Archival objects featured date from the late 1920s through to 2018 and span multiple continents. I curated each exhibition, determining its collections and the 800 plus archival items included. I wrote descriptions introducing audiences to the historical significance and implications of these ordinary and extraordinary objects: photos of Black soldiers in Iran during WWII; a picture of my grandmother as a girl in the 1930s outside Yankee Stadium; a first-edition autographed copy of Angela Davis' Women, Race and Class. Each exhibition was accompanied by a livestream discussion between an expert-interlocutor and myself and the series included three solo performances that I wrote and performed. The exhibitions reached audiences of over one thousand users with over twenty thousand views.25

Most items were exhibited in a somewhat standard museum-style format, however, I found montage and juxtaposition to be key tools in the presentation of the archive's audiovisual materials. There were hundreds of VHS cassette tapes in the archive. A few were Hollywood blockbusters and independent films, but the overwhelming majority were either related to Islamic studies and dawah (propagation) or were Umi's recordings of television programs. The former included three lectures, "Africa: The Sleeping Giant", "The Solution to South Africa: Christianity, Communism or Islam", and "The Birth and Death of Christianity" by Khalid Al-Mansur, a Black US American, that were delivered in South Africa and recorded and distributed by Ahmad Deedat's Islamic Propagation Centre. Recorded television programs were divided between soap operas, the Oprah Winfrey Show, and news programs. This included mainstream and local network news coverage of Black history, incidences of anti-Black violence, and post-9/11 content, but mostly episodes of the news program Like It Is, a Black public affairs news program hosted by journalist Gil Noble from 1968-2011. I cannot overstate the significance of Like It Is to this archive. I have many memories of watching Like It Is or being told to watch Like It Is, or phone calls telling my mother to "turn on Like It Is!" to catch whatever deeply informative and educational content was on that Sunday. Like It Is reflected the political and social interests and commitments my mother had and are threaded throughout the archive.

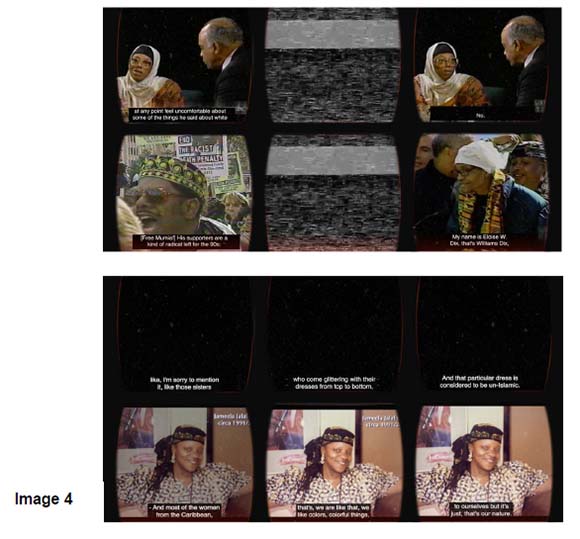

Considering the significance of the show, I included these recordings in the exhibition using montage. I worked with the filmmaker Shireen Alihaji to create a video montage of clips from Like It Is episodes interspersed with white tv fuzz. For the fifth exhibition, we created an eight minute montage that includes a segment from the May 1999 Like It Is episode "Malcolm X: Three African American Women who knew him" in which the three women (activists Khadijah Canton, Vicki Garvin and Jean Reynolds) praised Malcolm's radical thought; a few key seconds from mainstream network news show ABC 20/20's 1998 coverage of Hollywood support for political prisoner Mumia Abu Jamal; part of a speech delivered by political prisoner Imam Jamil Al-Amin/H. Rap Brown at a Muslim-led rally for Bosnia in Washington, D.C. in 1993; a clip from a Like It is interview with civil rights movement leader Gloria Richardson on the impact of Imam Jamil; a segment from the show's December 1998 episode "The Question of Leadership" where civil rights leaders Rev. M. William Howard, Dr. William Strickland, Pastor Prathia Hall, and Howard Dodson reflected on Black political leadership; and a closing clip from the African Burial Ground Dedication in New York City covered by Like It Is in October 2007 where long-time activist and New York City council member, Charles Barron, brought Eloise William Dix to the podium to speak in honor of her theretofore unsung work without which the remains of the Africans found in New York City would have been forgotten and desecrated.26 My simple note to exhibition visitors upon encountering the montage was "an invitation to contemplate the legacies of Black Power".

I also used montage and juxtaposition in the collection #BlackinMSA. Riffing off the social media hashtag,27 the collection offers a historical perspective on relationships between Black and non-Black Muslims through Amina's experience with the Muslim Students Association, an organization founded in 1963 to support students from majority-Muslim nations studying at North American universities.28 I created a video montage called "Modesty: Two Perspectives" that juxtaposes the voices and commentary of two Muslim women, an Arab immigrant woman and a Black US American woman. In the first audio clip, the Arab immigrant woman is lecturing at a session of the 1976 MSA conference. She is instructing women on modest dress and explains that the clothing women wear should not make men or others look, making "glittering jewelry" and "glittering threads...un-Islamic". Immediately following these remarks is audio from an oral history interview I conducted in 2013 with one of Umi's best friends, Jameela Jalal Uddin (d. 2018). In this excerpt of the interview, she explains that, despite this kind of instruction, Black Muslim women chose to practice modesty differently. They embraced a definition of modesty informed by their cultural backgrounds and, accordingly, embraced color and looking "pretty as a woman should". She considered that as part "of our [female] nature...and if someone else admire it, that's on them". The contrast of these two points of view is striking and made even more so by putting them side by side, giving exhibit visitors a more visceral access to the liveliness of the debate that ensues to this day. I incorporated these tools, montage and juxtaposition, in other collections as well as they are more dynamic forms of representation that better reflect the multidimensionality of lives lived.

Intimacy as Knowledge and Tradition

As part of my research for Umi's Archive I searched for my mother's college boyfriend, Jeff. He and she were more than romantic partners, they were partners in the struggle as students at OSU from around 1969 through to 1972, a powerful moment in world history. Upon viewing the online exhibitions, Jeff wrote me a letter praising the work, stating "it has the eye of a scholar, the passion of an activist and the heart of a child".29 I thought to myself, "yes, that's it!". Later, I was listening to an interview with the activist Malkiah Devich-Cyril where they spoke about the tremendous grief Black people experience, noting "instead of being crushed under the weight of this grief we turn it into something beautiful and useful, right? We do the mourning work (emphasis mine)".30 And I said to myself, "yes, that's it!". And, while preparing this essay, I returned to historian Jennifer Morgan's insight that "those who work on the subaltern, on people and places that are understood as outside of or marginal to the archival project of nation building" have "long grappled with a scholarly induced malady, a relationship to the research that positions us always on the brink of breakthrough and breakdown (emphasis mine)".31 And I said to myself, "yes, that's it!".

The "it", here, is my work on Umi's Archive, the mourning work that requires my scholarly training, my political commitments, and my heart to produce knowledge that is meaningful and even, perhaps, decolonial. I respect the warning from indigenous scholars that "decolonization is not a metaphor" and have hesitated to call it such. Yet I do see this work in the way that Scott, Hartman, McKittrick, and others offer us as a means for resisting and undoing colonial logics of the dualism between mind and body, the primacy of the written word, the absence of spirit, and the fallacy of objectivity. A resistance and undoing that manifest not only in the kind of work that is produced but in the work process itself.

Take for example, my feelings. As obvious as this might be for others, it took me a while to recognize how much feeling this project evokes for me. I, of course, was and will always grieve my mother's passing but, I had, despite what I know better, still bifurcated the research project of "Umi's Archive" from my own grieving process. In this binary, grief was crying after remembering, again, that she is gone, or feeling joy from a good memory or good dance session. The research was different, it was analysis that came with some wonder and reflection, but it was not feeling. Yet you cannot escape the feeling. I have come to note that when working with archival materials there is a point where the grief, the feelings, rise and will not be ignored. I cannot tamper down the feeling of sadness-the bittersweetness of her absence and presence- having left so much for me to still learn from and share with others. Indeed, at "the brink of breakthrough and breakdown".

When these feelings arise, it is time to take a break. This is a small, yet significant, act because by recognizing feelings and giving feeling space, I break a bit of the hold colonial logics has on me. I was operating by the "ambient belief that feeling and thinking are separate", a binary that gave rise to secular regimes of knowledge and scientific rationality.32 I realized, with reflection, that despite all my personal and scholarly knowledge, I was still underestimating how deeply eurocentrism and white supremacy shaped our structures of feeling, something my Umi, not inconsequentially, never underestimated. So, pausing and feeling is part of what it means to do this work, how I do this work, and continue to develop my own practice for these moments.

Feelings also informs how I access the archive and my analytical frames. I feel so much because of how deep my relationship was and that affords me an intimacy with the archive and an intimate knowledge of it. There is a collection of audio cassette tapes from the Islamic studies classes my mother took in the mid-1970s. These classes were held in New York City and Northern New Jersey, initiated by fellow Black Muslim women converts and friends, Kareemah Abdul-Kareem and Aliyah Abdul-Karim, and taught by Dr. Sulaiman Dunya, an Egyptian scholar trained at Al-Azhar. The classes cover topics such as ritual prayer and in the recordings my mother asks a lot of questions, pushing, at one point, Dr. Dunya's patience, who on all the tapes is a very measured and open teacher. In one of the recordings, she asks about a famous verse of the Qur'an and while doing so, stumbles over its name: ayat al-Kursi. I immediately picked up on her uncertainty, how she stumbled. It stood out to me because she was the one that taught me that very verse when I was a child. I am uncertain if another ear would have noticed the stumble as significant, but I do know that it was my close experience with her and that ayat that gave me access to the significance of the moment and what it marked about her narrative. Hers is not the only voice in the recordings. There are voices of other Black women who are also new Muslims, but I only recognize one voice, Kareemah Abdul-Kareem's.

Yet as they ask question after question to their teacher-these women did not come to play-I hear or rather feel their urgency and eagerness to learn and understand. Feeling that offered me a deeper and different vantage point towards understanding the conversion narratives of the period. It helped make sense of all the religious literature from that period that my mother held onto. It amplified the significance of what conversion meant to these individual women and to the broader conversation of Islam, spirituality, and the Black experience in the United States. Critically, I gained this knowledge from feeling what I heard them feel.

As I return to the Black feminist scholarship that inspires me, I am reminded that I am not alone in my feelings and that the kind of intimacy that comes from deep relation is not limited to mothers and daughters. In the epilogue of Passed On: African American Mourning Stories, A Memorial, Karla FC Holloway narrates the story of her visit to Billie Holiday's grave as part of her research for the book in which visiting tombstones became "an intimate, sojourn among my cultural kin".33 At Holiday's gravesite, she sings "God Bless the Child", causing an older white couple nearby to ask her if she knew Billie Holiday. Holloway describes her response: "Before I could help it, I heard myself say oh yes, she's my great aunt. Of course, it wasn't all true, but at that moment I felt like kin".34 To feel like kin, here, is not about blood but, rather, informed by the ties that can, and have, bound Black people to each other from our fictive kin in diaspora ("sippi" to play cousins) to the fierce protective affect everyday Black folk have for Black heroes of all stripes.35 I feel this feeling in Barbara Ransby's introductory reflection in her biography of the civil rights leader, Ella Baker, where she describes her "journey into Ella Jo Baker's world" as a "personal, political and intellectual journey" and makes no apology for admiring Baker because "she [Baker] earned it".36 Likewise, I feel this feeling in Sisonke Msimang's reflection on writing about Winnie Mandela to protect her from the "gendered double-standard" in which a man's sexual life is rendered inconsequential to their political legacy but, for a woman like Mandela, results in her complex and dynamic political life being demonized and made into a jezebel tale.37

Msimang is keen to point out her objective is not hagiography; she does not "downplay Winnie Mandela's violence". Yet, her feelings lead her to make a critical analytical intervention to use "intimacy and familiarity" as tools to write about and to Mandela in modes of admiration and disappointment.38Intimacy and familiarity producing both feelings of admiration and disappointment reminds me of the mother-daughter relationship. As much as familial intimacy can blind you to the imperfections, as is feared, it can also make flaws more apparent due to both the proximity and the complicated relationship between mothers and daughters and/or in my case single mothers and oldest daughters. Indeed, all feelings are not "good". Russert also writes about finding disappointment in the archive in another setting. Working on the friendship albums of free Black women in nineteenth century Philadelphia, she does not find the "narratives of resistance" she expects. Rather, she finds the women's cultural production "steadfast" in its "fidelity" to the gendered conventions of the period.39 Critically, Russert chooses to lean into, rather than dismiss, the disappointment and finds it analytically generative.40 She comes to see that fidelity to conventions indexes an attempt to project stability at a time where Black women's lives were precarious because, much like today, the project of freedom was incomplete.41 In each of these instances Black feminist scholars narrate developing a deep and intimate relationship with the ancestors they write about and embrace this intimacy in a direct challenge to the thinking/feeling binary.

Critically, though intimacy gives access to knowledge, it is not totalizing. It does not give you access to everything there is to be known because, as we know, our knowledge, wherever we acquire it, is always partial. However, intimacy does provide a more dynamic knowing. In colonial epistemologies, we are only supposed to approach our work with the "eye of a scholar" and that is what makes it legitimate research, valuable, and the hallmark of the Euroamerican intellectual tradition. However, I have found using only one lens inhibits understanding. In fact, this project is at its best when I am all of those things at the same time, scholar, activist-artist, and child, opening up knowledge rather than foreclosing it as "objectivity" discourse presumes. Moreover, as Devich-Cyril theorized, drawing on all those dimensions is the hallmark of a Black Radical Tradition, one that I step into when I am moved by "all the things" to build something beautiful and useful, to build Umi's Archive.

References

Ahmed, Sarah. "Making Feminist Points." Feministkilljoys (blog), September 11, 2013. https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/09/11/making-feminist-points/. [ Links ]

American Civil Liberties Union. "Leaked FBI Documents Raise Concerns about Targeting Black People Under 'Black Identity Extremist' and Newer Labels," August 9, 2019. http://www.aclu.org/press-releases/leaked-fbi-documents-raise-concerns-about-targeting-black-people-under-black-identi-1. [ Links ]

Campt, Tina. Listening to Images. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017. [ Links ]

Cite Black Women. "OUR STORY." Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.citeblackwomencollective.org/our-story.html. [ Links ]

Ewing, K.T. "Fugitive Archives: Black Women, Domestic Repositories, and Hoarding as Informal Archival Practice." The Black Scholar 52, no. 4 (October 2, 2022): 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2022.2111653. [ Links ]

Freeney Harding, Rosemarie, and Rachel E. Harding. Remnants: A Memoir of Spirit, Activism, and Mothering. Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2015. [ Links ]

Gilmore, Ruth. "Introduction." In Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta, xi-xiv. Verso, 2017. [ Links ]

Hartman, Saidiya. "Venus in Two Acts." Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 114. [ Links ]

Hartman, Saidiya V. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. First edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019. [ Links ]

Helton, Laura, Justin Leroy, Max A. Mishler, Samantha Seeley, and Shauna Sweeney. "The Question of Recovery: An Introduction." Social Text 33, no. 4 (125) (December 1, 2015): 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315766. [ Links ]

Holloway, Karla FC. Passed On: African American Mourning Stories, A Memorial. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385073. [ Links ]

Lewis, Desiree, and Gabeba Baderoon, eds. Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2021. [ Links ]

McKittrick, Katherine. "Mathematics Black Life." The Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (2014): 16-28. [ Links ]

Mintz, Sidney W. and Richard Price. The Birth of African-American Culture: An Anthropological Perspective. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992. [ Links ]

Morgan, Jennifer L. "Archives and Histories of Racial Capitalism: An Afterword." Social Text 33, no. 4 (125) (December 1, 2015): 153-61. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315862. [ Links ]

Msimang, Sisonke. "Winnie Mandela and the Archive: Reflections on Feminist Biography." In Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, edited by Desiree Lewis and Gabeba Baderoon, 15-27. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2021. [ Links ]

Omowale, Yusef. "We Already Are." Sustainable Futures (blog), September 3, 2018. https://medium.com/community-archives/we-already-are-52438b863e31. [ Links ]

Ransby, Barbara. Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003. [ Links ]

Rusert, Britt. "Disappointment in the Archives of Black Freedom." Social Text 33, no. 4 (125) (December 1, 2015): 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315874. [ Links ]

Schaefer, Donovan O. Wild Experiment: Feeling Science and Secularism after Darwin. Durham: Duke University Press, 2022. [ Links ]

Swenson, Kyle. "J. Edgar Hoover Saw Dick Gregory as a Threat. So He Schemed to Have the Mafia 'Neutralize' the Comic." Washington Post. Accessed August 2, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.co m/news/morn ing-mix/wp/2017/08/22/j-edgar-hoover-saw-dick-gregory-as-a-threat-so-he-schemed-to-have-the-mafia-neutralize-the-comic/. [ Links ]

The Emergent Strategy Podcast: "Radical Grievance with Malkia Devich Cyril," n.d. https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/emergentstrategy/episodes/Radical-Grievance-with-Malkia-Devich-Cyril-e1kktn6. [ Links ]

The Ohio State Latern. "Lantern Notes Seized." June 28, 1971. [ Links ]

U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). "FBI Documents on Richard 'Dick' Claxton Gregory." Accessed August 2, 2022. http://archive.org/details/FBI-Dick-Gregory. [ Links ]

Submission Date: 9 April 2023

Acceptance Date: 10 July 2023

i Su'ad Abdul Khabeer is a scholar-artist-activist whose work explores issues of race and Blackness, Islam in the United States and hiphop music and culture. She is an associate professor of American Culture at the University of Michigan.

1 Amina Amatul Haqq, interview by Rog Walker, Bronx, NY, May 16, 2017.

2 Rosemarie Freeney Harding, and Rachel E. Harding. Remnants: A Memoir of Spirit, Activism, and Mothering (Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2015); Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Saidiya V. Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. First edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019).

3 K.T. Ewing, "Fugitive Archives: Black Women, Domestic Repositories, and Hoarding as Informal Archival Practice," The Black Scholar 52, no. 4 (2022): 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2022.2111653.

4 Kyle Swenson, "J. Edgar Hoover Saw Dick Gregory as a Threat. So He Schemed to Have the Mafia 'Neutralize' the Comic," Washington Post, August 22, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/08/22/j-edgar-hoover-saw-dick-gregory-as-a-threat-so-he-schemed-to-have-the-mafia-neutralize-the-comic/.

5 "Lantern Notes Seized," The Ohio State Latern, June 28, 1971.

6 Mattias Gardel, In the name of Elijah Muhammad: Louis Farrakhan and the Nation of Islam (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996).

7 "Leaked FBI Documents Raise Concerns about Targeting Black People Under 'Black Identity Extremist' and Newer Labels," American Civil Liberties Union, http://www.aclu.org/press-releases/leaked-fbi-documents-raise-concerns-about-targeting-black-people-under-black-identi-1. Adam Goldman and Matt Apuzzo, "With cameras, informants, NYPD eyed mosques," Associated Press, February 23, 2012.

8 Laura Helton et al., "The Question of Recovery: An Introduction," Social Text 33, no. 4 (125) (2015). https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315766: 2.

9 Saidiya Hartman, "Venus in Two Acts," Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 14.

10 Katherine McKittrick, "Mathematics Black Life," The Black Scholar 44, no. 2 (2014): 18.

11 David Scott, "That Event, This Memory: Notes on the Anthropology of African Diasporas in the New World," Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1, no. 3 (1991): 261 -84.

12 Scott, "That Event, This Memory," 263.

13 Scott, "That Event, This Memory."

14 Sara Ahmed, "Making Feminist Points," feministkilljoys (blog), September 11, 2013, https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/09/11/making-feminist-points/

15 "Our Story," Cite Black Women, accessed April 5, 2023, https://www.citeblackwomencollective.org/our-story.html.

16 Ruth Gilmore, "Introduction," in Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta (Verso, 2017): xiv.

17 Yusef Omowale "We Already Are," Sustainable Futures, September 3, 2018, https://medium.com/community-archives/we-already-are-52438b863e31.

18 Ewing, "Fugitive Archives," 44

19 Ewing, "Fugitive Archives," 44

20 Ewing, "Fugitive Archives."

21 I used this method with my mother's large library. I hired a research assistant, Carl Hewitt, to create a catalog of the books. I determined what books were particularly significant to her by their age, by her marginalia, or if they related to themes that were emerging for me in the archive. The rest I gave away to the book lovers in her life. Books were also donated to Believers Bail Out for distribution to incarcerated Muslims, in line with my mother's politics. I also engaged a similar process with her smaller music collection and very LARGE wardrobe.

22 Dr. Jallicia Jolly and Enno Knepp worked with me at different stages of the project. My office building is relatively new and fairly temperature-controlled, but I am seeking more security archivally-speaking. My long term goal is to donate materials to a library.

23 My first book, Muslim Cool: Race, Religion, and Hip Hop in there United States, is paired with my performance ethnography, Sampled: Beats of Muslim Life, a one-woman show grounded in the tradition of embodied knowledge and the research-to-performance methods inaugurated by anthropologists Zora Neale Hurston and Katherine Dunham.

24 I was the recipient of the Soros Equality Fellowship in 2019 that supported the exhibition series.

25 This success was made possible by the team of eight people, including Kareem Lawrence, Belinda Bolivar, Maysan Haydar, Fatima Hedadji, Belquis Elhadi, and Zainab Baloch, who I worked with on everything from web design and research to social media posts. They were my sounding board and key supporters. I also want to acknowledge the librarians, particularly the digital research team at the University of Michigan, who played a fundamental role in helping me actualize the exhibition series from creating metadata to building an effective team. I also worked with a digital imaging specialist, Sally Bjork, also at the University of Michigan, to digitize artifacts for the series. The full digitization of the archive is a monumental task that I am still contemplating.

26 In 1991, 15,000 intact human skeletal remains of enslaved and free Africans were found in a construction site in lower Manhattan. Community outcry and activism led to the reinterment of the remains and a memorial site.

27 Using the hashtag #BlackInMSA, the anti-racism organization, MuslimARC, initiated a conversation on the experiences of Black Muslim undergrads with the national student organization, the Muslim Student's Association. Since then, the hashtag has been used to raise awareness of anti-Blackness in Muslim campus groups and beyond.

28 In 1983, MSA expanded to become the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA) and, today, aspires to facilitate the religious, cultural, and civic development of all Muslims, irrespective of migration status. Both MSA and ISNA have been simultaneously useful and alienating spaces for Black Muslims in North America.

29 Jefferson Guinn, e-mail to author, June 30, 2021.

30 Radical Grievance with Malkiah Devich-Cyril, June 30, 2022, in The Emergent Strategy Podcast, https://podcasters.spotify.com/pod/show/emergentstrategy/episodes/Radical-Grievance-with-Malkia-Devich-Cyril-e1kktn6.

31 Jennifer L. Morgan, "Archives and Histories of Racial Capitalism: An Afterword," Social Text 33, no. 4 (125) (2015): 153-61, https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315862.

32 Donovan O. Schaefer, Wild Experiment: Feeling Science and Secularism after Darwin (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022): 5.

33 Karla FC Holloway, Passed On: African American Mourning Stories, A Memorial (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002): 197.

34 Holloway, Passed On, 197.

35 In a practice seen throughout the Diaspora, "sippi" was used in Suriname to refer to the person who traveled the middle passage with you and continues as "sibi" to indicate a close non-biological bond (See Mintz and Price, The Birth of African-American Culture). In the US, "play cousin" also describes non-biological familial ties.

36 Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 2.

37 Sisonke Msimang, "Winnie Mandela and the Archive: Reflections on Feminist Biography," in Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, ed. Desiree Lewis and Gabeba Baderoon (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2021), 15-27.

38 Msimang, "Winnie Mandela and the Archive: Reflections on Feminist Biography."

39 Britt Rusert, "Disappointment in the Archives of Black Freedom," Social Text 33, no. 4 (125) (2015): 21.

40 Rusert, "Disappointment in the Archives of Black Freedom."

41 Rusert, "Disappointment in the Archives of Black Freedom."