Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

African Human Mobility Review

versão On-line ISSN 2410-7972

versão impressa ISSN 2411-6955

AHMR vol.3 no.2 Cape Town 2017

ARTICLES

Security Risk and Xenophobia in the Urban Informal Sector

Sujata RamachandranI; Jonathan CrushII; Godfrey TawodzeraIII

ISouthern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre, Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb St West, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L6C2

IIInternational Migration Research Centre, Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb St West, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada N2L6C2. Email address: jcrush@balsillieschool.ca

IIIDepartment of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Limpopo, P. Bag X1106, Sovenga

ABSTRACT

Whenever there are violent attacks on refugee and migrant businesses in South Africa's informal sector, politicians, officials and commissions of enquiry deny that xenophobia is a driving force or indeed exists at all in the county. A new strain of nativist research in South Africa does not deny the existence of xenophobia but argues that it is an insignificant factor in the violence. It is argued that because South African and non-South African enterprises are equally at risk, the reasons for the violence are internal to the sector itself. This paper critiques this position on the basis of the results of a survey of over 2,000 enterprises in the contrasting geographical sites of Cape Town and small town Limpopo. The survey results reported in this paper focus on security risks and the experience of victimisation and the experience of the two groups of enterprise operator are systematically compared. The findings show that while both cohorts experience many of the same security risks, refugee operators are significantly more exposed to most threats including verbal abuse, theft, unprovoked attacks and harassment by law enforcement agencies. Far from being irrelevant, xenophobia is an important additional risk for refugee entrepreneurs, as they themselves clearly recognise.

Keywords: Security risks, informal sector, xenophobia, refugee entrepreneurs, South African entrepreneurs.

Introduction

In early 2015, South Africa experienced a new wave of violent attacks on migrants, the culmination of several years of more localised but escalating collective violence targeting migrant-owned businesses in the country (Crush & Ramachandran, 2015a). After May 2008, when South Africa had witnessed a previous round of large-scale violence against migrants, a decisive shift had occurred in state discourses and management of xenophobia. The government's stance towards xenophobia had moved from a lack of acknowledgement of its presence and policy neglect to public rejection and denial of its very existence in the country (Crush & Ramachandran, 2014). This shift framed the way in which government interpreted and responded to renewed violence in 2015. This response had three key elements: first, denial of the existence of xenophobia and as an explanation for the violence; second, blaming migrants for their own victimisation; and third, attributing ongoing violence against migrant-owned businesses as the work of criminal elements (Bekker, 2015; Crush & Ramachandran, 2015a; Misago, 2016).

The major formal government response to the international and broader African outrage over the violence was the establishment of an Inter-Ministerial Committee on Migration (IMC) housed in the Presidency. As many as fifteen government ministers sat on the IMC, which was expanded in March 2017 to include all provincial premiers and the South African Local Government Association (SALGA). The stated brief of the IMC was to address "all the underlying causes of the tensions between communities and the foreign nationals" (Williams, 2015), which appeared to indicate that the problem of xenophobia was finally being taken seriously at the highest levels of government. The reality proved to be very different. In April 2015, the IMC launched Operation Fiela ("sweep" in Sesotho), which was officially described as "a multidisciplinary interdepartmental operation aimed at eliminating criminality and general lawlessness from our communities [...] so that the people of South Africa can be and feel safe" (Gov.za, 2015). As a response to xenophobic violence, the actions of the IMC seemed grossly inappropriate and were roundly condemned by international and local human rights organisations. Lawyers for Human Rights, for example, characterised Operation Fiela as "state-sponsored xenophobia" and "institutional xenophobia" that blurred stark differences between "criminals" and migrants, while deepening the divide between citizens and foreigners by bolstering negative perceptions, instead of correcting them" (Jordaan, 2015; LHR, 2015).

A central component of Operation Fiela was a massive police and army drive to harass migrants and migrant-owned businesses (Nicolson, 2015a). The IMC made its conclusions about the 2015 anti-migrant violence known in Parliament. According to the Chair, Minister Jeff Radebe, the primary cause was uncontrolled migration and "increased competition arising from the socio-economic circumstances in South Africa." Foreign nationals were placing a strain on government services and "dominating trade in certain sectors such as consumable goods in informal settlements which has had a negative impact on unemployed and low skilled South Africans." These unsubstantiated findings - essentially blaming the violence on migrants and the poor enforcement of migration controls - were compounded by the Chair's observation at a press conference that "as the Inter-Ministerial Committee, we've concluded that South Africans are not xenophobic" (Davis, 2015).

The Parliamentary Ad Hoc Committee constituted to investigate the 2015 violence reached the same conclusions. In the course of deliberations to finalise their report, members of the Committee made highly pejorative statements about migrants (PMG, 2015). They indicated that the competitive advantage enjoyed by foreign-owned businesses was achieved through the use of "unfair, competitive trading practices." They emphasised that the violence and looting directed at migrant businesses and properties was the direct result of "competition for trading spaces" and "overcrowded trading spaces" and said there was no "credible evidence" that migrant-run businesses created employment. At public consultations, the committee chair chastised the media for using the term 'xenophobia' to describe episodes of violence targeting migrant-operated businesses (Masinga, 2015). She reportedly characterised the violence as "criminals [...] targeting shops to get food and had nothing to do with foreign nationals." The Committee's final report reached the conclusion that xenophobia did not exist, explaining the violence as the actions of criminals "who are often drug addicts" (PJC, 2015: 35; Nicolson, 2015b).

Xenophobia denialism was also evident in the report of the KwaZulu-Natal Special Reference Group (SRG), an independent commission of enquiry appointed by the provincial government and headed by Judge Navi Pillay (formerly the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights) (SRG, 2015). The SPG argued that the immediate cause of the outbreak of violence was "deliberate efforts of select individuals, some of whom had interests in the informal trading sector, to drive away competition by foreign national-owned businesses [.] These deliberate efforts sparked the outbreak of widespread incidents of criminality, violence and looting of properties owned by foreign nationals" (SRG, 2015: 9-10). Furthermore, "many of the perceptions of foreign national traders, although largely unfounded, contributed to heightened tensions" (SRG, 2015: x). The SRG studiously avoided labelling the violence as xenophobic or seeing xenophobia as a contributing or even motivating factor. At most, it conceded that "the violent attacks against foreign nationals were, in some measure, fuelled by dominant and negative perceptions that exist amongst locals and foreign nationals about one another" (SRG, 2015). However, it is hard to see how the attitudes of foreign nationals could be responsible for their own violent victimisation and none of the mob violence was perpetrated by migrants on South Africans.

This entrenched and contradictory tendency - denying the existence of xenophobia while simultaneously blaming migrants in ways that border on the xenophobic - has been a defining characteristic of official responses to the escalating attacks nationwide on migrant and refugee-owned informal businesses (Crush & Ramachandran, 2015a). If mere criminality is the source of the plague of chronic violence against non-South African entrepreneurs, we might expect South Africans operating in the same areas to be equally affected. Some researchers have claimed that this is, in fact, the case (Charman & Piper, 2012; Charman et al., 2012; Piper & Charman, 2016). They argue that the attacks on informal businesses in South Africa are structural in nature, shaped by competition and other localised factors other than nationality or xenophobia. In a study of Delft in Cape Town, Charman and Piper (2012: 81) maintain that "despite a recent history of intense economic competition in the spaza market in which foreign shopkeepers have come to dominate, levels of violent crime against foreign shopkeepers [...] are not significantly higher than against South African shopkeepers." They conclude, as a consequence, that there is no need to invoke xenophobia to explain violence against non-South African informal enterprises, a conclusion that ironically echoes that of government officials and the commissions of enquiry. Rather, "some combination of criminality and economic competition seems to explain the violence" (Charman & Piper, 2012: 89).

In a larger study, Piper and Charman (2016: 332) examine patterns of violence in three cities and conclude that "it simply is not true that [...] South African shopkeepers experience less violent crime than foreign shopkeepers" and therefore that "the chance of being violently targeted is less about nationality, and more about whether you keep prices low and (presumably) profits high." In this paper, we provide alternate evidence that contradicts the conclusion about the unimportance of nationality in explaining citizen and police violence in the informal sector. The paper draws on a study of over 2,000 informal sector businesses in Cape Town and Limpopo Province, half owned by refugees and half owned by South Africans. The methodology is described in Crush et al (2015).

Security Risks and Vulnerabilities

The sustainability of informal enterprises is shaped by the challenges they encounter and the manner in which they are able to effectively manage business risks. A sizeable body of research has shown that small enterprises in the South African informal economy face significant business obstacles, preventing them from maximising their potential (Abor & Quartey, 2010; Crush et al., 2015; Grant, 2013; Thompson, 2016; Willemse, 2011). These business risks include limited trading spaces; lack of access to loans from formal financial institutions; few technical, financial and business-related skills; excessive licensing or regulatory restrictions on business operations; lack of a well-defined policy framework for such operators; intense competition with other similar businesses; and lack of infrastructure such as adequate storage facilities (Callaghan & Venter, 2011; Gastrow & Amit, 2015; Ligthelm, 2011; Rogerson, 2016a, 2016b; Venter, 2012).

In South Africa, business risks are compounded by security risks because of the extremely unpredictable and often dangerous operating environment.

These security risks are of several main types. In many cities, the informal economy is regarded with suspicion and even outright hostility by municipalities, and is seen as a reservoir of crime and illegality (Rogerson, 2016a). The resulting oppressive regulatory environment is enforced by the South African Police Services (SAPS) and by municipal police who make regular raids, issue fines and confiscate goods (Rogerson, 2016b; Skinner, 2008). Harassment by police and enforcement officials is compounded by police conduct including demand for bribes and illegal confiscation of business inventory/stock. Informal businesses are regular targets of national (Operation Fiela), provincial (Operation Hardstick in Limpopo) and city-wide (Operation Clean Sweep in Johannesburg) police purges of the streets and large-scale seizure of stock. The courts have generally concluded that these operations are largely targeted at the foreign-owned businesses. A 2014 Supreme Court (2014: 25) judgment striking down Operation Hardstick in Limpopo, for example, left the Court with "the uneasy feeling that the stance adopted by the authorities in relation to the licensing of spaza shops and tuck-shops was in order to induce foreign nationals who were destitute to leave our shores." The obverse of police misconduct is a failure to provide consistent protection when businesses are under threat or are victims of crime and other violence.

Many informal businesses service the basic needs of low-income, crime-ridden communities. This means that, by definition, they are vulnerable to opportunistic and often violent crime in the form of theft, robbery and assault. There is also a clear pattern of escalating group or mob violence in many parts of the country that is increasingly directed at informal businesses (Crush & Ramachandran, 2015a). Nationwide mob violence and looting in May 2008 and early 2015 were the most high-profile examples but in the years in between and since there have been numerous more localised attacks. These assaults generally involve widespread looting, destruction and burning of property and physical assault and murder. There is considerable evidence that this form of violence is targeted almost exclusively at foreign-owned businesses and, therefore, cannot be as easily dismissed as non-xenophobic.

The question to be addressed is whether these security risks - government purges, police misconduct, opportunistic crime and mob violence - affect South African and non-South African informal businesses with equal intensity. If we accept the argument of Charman and Piper (2012) that xenophobia is not a factor, then we would expect there to be no difference between the frequency and severity with which the two groups are affected by these risks. If, however, there is systematic evidence that these risks are felt or experienced more severely by non-South African migrant informal business owners, then xenophobia needs to be reintroduced as an explanatory factor.

As part of the 2016 survey of 2,000 informal businesses in Cape Town and Limpopo, respondents were asked a series of questions about the frequency with which they had experienced various security-related risks. We rely here on self-reporting since police crime statistics are unavailable and unreliable (particularly since many incidents go unreported or unprosecuted when they are reported). In addition, we accept the argument of Charman and Piper (2012) that risk may be under-reported since many informal businesses are comparatively new and may not yet have been exposed to these risks. At the same time, it is important to note that under-reporting is less likely amongst South Africans since they have a longer history of business operations in Cape Town and Limpopo.

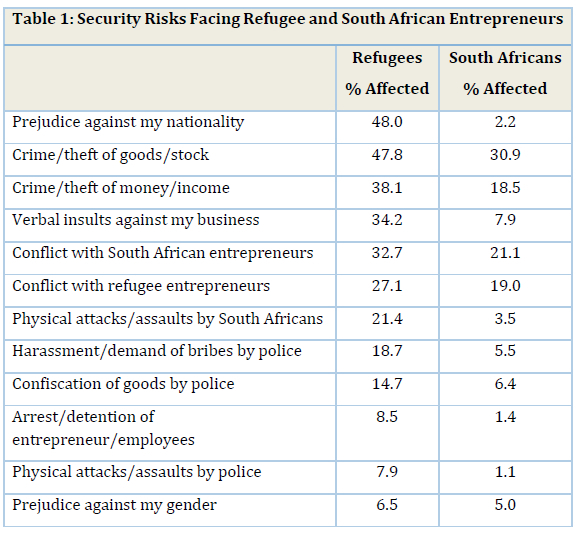

Table 1 presents the aggregated results of the security risks question for the two groups of entrepreneurs. First, it is clear from the table that not every South African and refugee respondent has been affected by the stated risks. Indeed, the majority of both groups have not been affected to date. This is an important initial finding because it does suggest that most informal entrepreneurs are able to run their businesses without any significant threat or interference. This may be because of where they are located or the measures and precautions they take to protect themselves. Second, it is clear that South Africans are not completely immune from any of these risks. Nearly one-third had been affected by robbery of their stock and nearly 20% had had income stolen. The degree of vulnerability to other security risks was much lower but not non-existent. To this extent, therefore, Piper and Charman (2016) are correct that South Africans in the informal sector are also victims of crime. But there is no support for their contention that South Africans and non-South Africans are equally at risk or victimised.

On every single count, the proportion of refugees who had been affected was higher, sometimes significantly so. For example, 47% of refugees cited prejudice against their nationality as a risk to their business (compared to only 2% of South Africans). Or again, 34% of refugees were affected by related verbal insults against their business, compared to only 8% of South Africans. 48% of refugees, compared with 31% of South Africans, had been affected by theft of their goods and stock. Similarly, 38% of refugees, compared with 19% of South Africans, had been affected by theft of their income. Refugees reported higher levels of conflict with South African competitors (33%) than South Africans did with refugees (19%) and with other South Africans (21%).

Interestingly, refugees also reported higher levels of conflict with other refugee businesses (27%). The precise details and outcomes of such conflicts need further research, but suggest that we cannot assume that refugees are a homogenous group with identical interests.

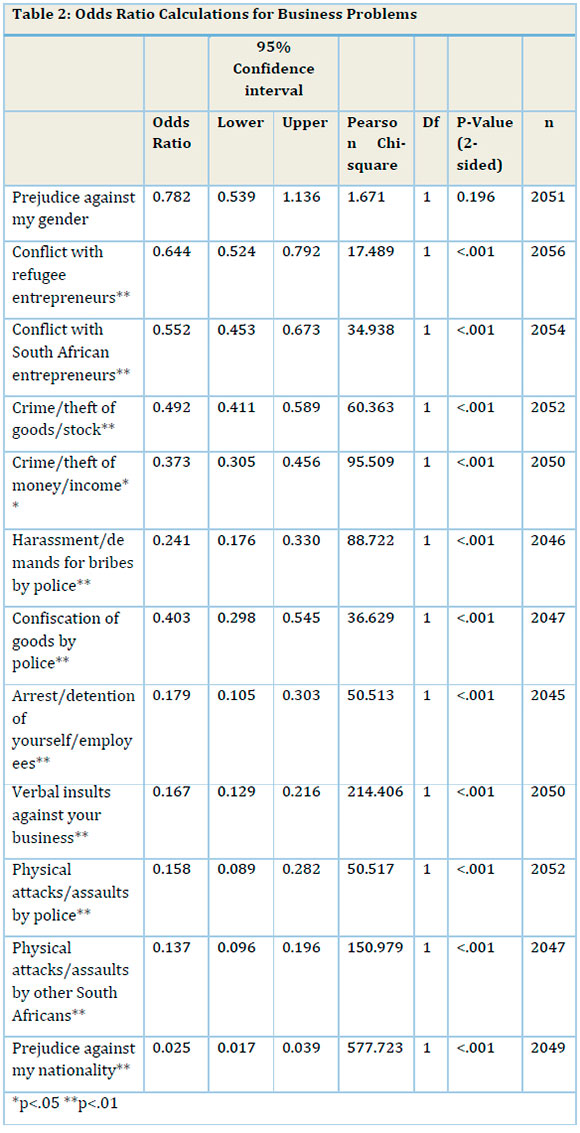

Table 2 statistically validates the descriptive comparisons that suggest that refugees are more likely than South Africans to be affected by the various security risks. The difference in the frequency distributions is statistically significant at an alpha of 0.01 according the Pearson's Chi-Square (x2(2048)=490.678, df=3, p<.001) and the Fisher's Exact Test (531.104, p<.001). South African entrepreneurs had lower odds of experiencing every potential risk on the list. Refugees were nearly three times as likely to be victims of theft of income and five times as likely to be subject to demands for bribes by police. The odds of a refugee entrepreneur being physically assaulted, experiencing prejudice and being arrested and detained were over five times higher than for South Africans.

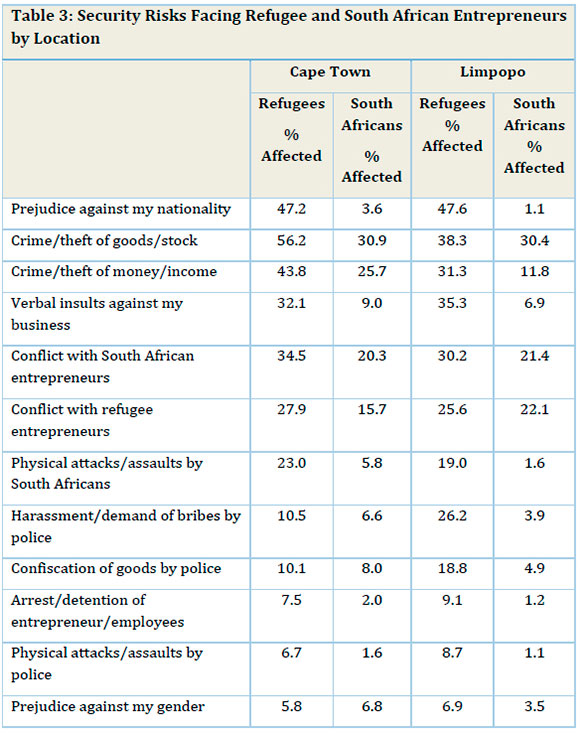

In theory, we might expect to see higher degrees of informal business security risks for both groups in large cities such as Cape Town compared to the much smaller towns of Limpopo (Table 3). In the case of refugees, and with the exception of prejudice and verbal insults and treatment by police, Limpopo was indeed safer than Cape Town. For South Africans, Cape Town was also a more dangerous place to run a business. For example, 56% of refugees and 31% of South Africans had experienced theft of goods in Cape Town. In Limpopo, the equivalent figures were 38% and 30%, a much lower spread than in Cape Town. In both locations, however, the risks are significantly higher for refugees than South Africans. Indeed, refugees in Limpopo were less secure than South Africans in both Limpopo and Cape Town. Theft of goods had affected 38% of refugees in Limpopo, compared with around 30% of South Africans in both Limpopo and Cape Town. Or again, 31% of refugees in Limpopo had experienced theft of money, compared with 12% of South Africans in Limpopo and 26% in Cape Town. Some 19% of Limpopo refugees had experienced physical assault or attack, compared with 2% of South Africans in Limpopo and 7% in Cape Town.

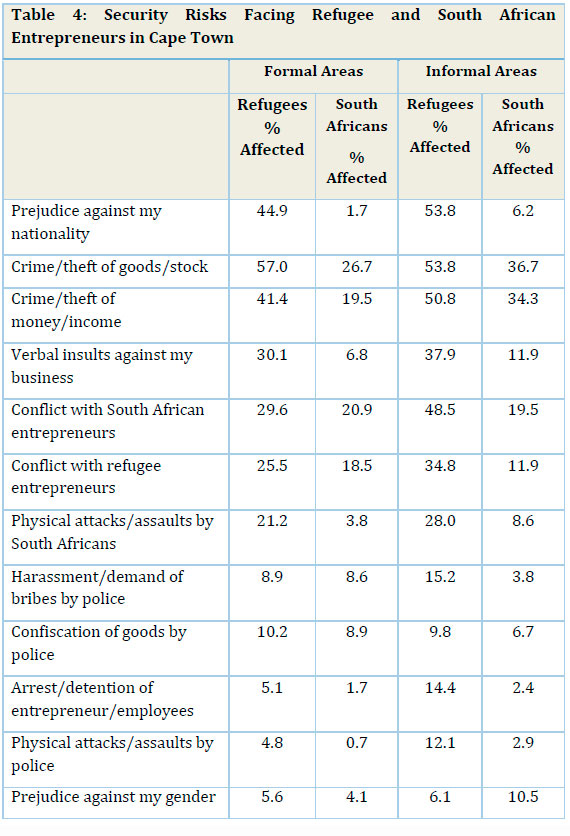

Another common belief is that security risks are higher in informal settlements than in other parts of the city, particularly as many of the reports of violence against informal businesses come from the latter areas and general crime levels are also much higher. To test this hypothesis, we focused only on Cape Town and divided refugees and South Africans into two groups according to their operation in either an informal or formal part of the city (Table 4). In the case of both refugees and South Africans, the risks are higher in informal settlements across almost all indicators. However, the difference in the degree of risk between refugees and South Africans is significantly greater in informal settlements than it is in formal areas of the city. The only indicator where formal areas are riskier for both is the chance of having goods confiscated by the police. Since the police barely venture into large swathes of informal settlements, this is not surprising. Refugees are slightly more likely to experience theft of goods in the formal versus informal areas (57% versus 54%), but the difference is small and indicates that this is a major risk for the majority of businesses irrespective of location.

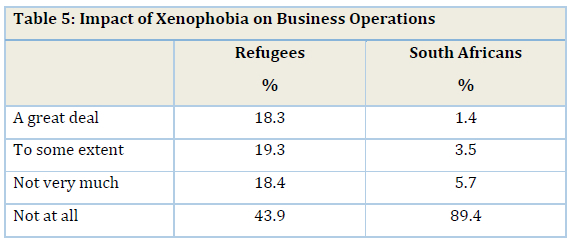

Unsurprisingly, refugees were far more likely than South Africans to say that their business operations had been negatively affected by xenophobia: 38% versus 5% (Table 5). There are two possible reasons for South Africans being affected: first, when collective violence occurs at a particular localised settlement, it is possible that in the general chaos and mayhem, South African-owned businesses may also be caught up in the looting and vandalism. As one South African owner noted "when these attacks start, it becomes difficult for us to move and every business becomes a target. Xenophobia does not only affect foreigners, it affects everyone" (Interview, 3 March 2016). A second explanation is that there are cascading, spill-over effects on those South African small businesses with cooperative, dependent relationships and linkages with affected migrant-operated businesses (Peberdy, 2017).

Strategies of Self-Protection

The dangerous and unpredictable environment in which informal entrepreneurs ply their trade in South African cities presents serious security challenges. It is clear from the previous section that while both groups are affected, refugees are much more vulnerable than South Africans to a range of risks. There is no a priori reason why this might be the case, other than the fact that refugees are targeted because their presence, which is viewed by citizens and officials as unwelcome and even illegitimate. This was certainly the view of most of the refugees interviewed for this study who consistently identified the manifestations of xenophobia as the major security problem they faced:

Some [customers] swear at me, my customers sometimes steal from me and whenyou catch them, they tell [you] harshly thatyou are a foreigner. And thatyou need to go back to your country. You are always faced with difficulties when you are a foreigner and as such you need to be patient and know how to deal with different kinds of people. There is too much disrespect here from South Africans because even someone who is way younger than you, they can swear and say nasty things to you if you are a foreigner. And they tell straight that South Africa is their country (Interview with Somali refugee, 12 March 2016).

If you are a foreigner, you are always affected by xenophobia. There is no way that you can live here and not be affected. Xenophobia starts from your customer. Some customers are very rude and if you respond, they will talk to you in their own language and scold you and then tell you to go back [to your country]. They have bad words for foreigners. Many times, my business was robbed when I was in Johannesburg. It was because I was a foreigner because they rarely stole from locals. Sometimes criminals would come to you and askyou to give them money and they would just askyou the foreigner. Why not the local people? That is xenophobia (Interview with Ethiopian refugee, 19 March 2016).

Xenophobia affect[s] us all. We know who we are. We are foreigners and that doesn't change. Nothing changes the reality. We live under alert anytime no matter the set up in which we are operating in. We always know that the same people we are dealing with can anytime become a danger to us. It is difficult to trust any person in South Africa. The person who is with you here today, when there is a protest and foreigners are being attacked, he will be the first to attackyou. There is no safety. I have not been attacked but I have seen other people being attacked and it is serious. It kills your business and it can also kill you (Interview with Congolese refugee, 25 February 2016).

Xenophobia is the most critical problem. I have been directly affected and have been caught up in the troubles. People have harassed me a lot, just talking like they want to kill you or to burn you or other such things. But that was when I was in Durban. Here [Cape Town] I have not been harassed. But there are many people who have been victims. They have been harassed and their goods destroyed, especially when there are strikes. The people just target anything that they can get. They are very cruel and they do not care what the owner will do to survive (Interview with Congolese refugee, 19 February 2016).

Xenophobia affects everyone who is a foreigner. When people loot your shop is that not xenophobia? When they chase you away from operating in an area because you are a foreigner that is xenophobia. There is xenophobia here, everywhere in this country. I have friends in other parts of the country, it is xenophobia where they live. I think South Africa is the only country with such xenophobia. I have been affected many times. When I was in Gugulethu, we were robbed. That was xenophobia because they were robbing foreign-owned shops. Here I have been affected once during a strike and they took some things from the shop. So, xenophobia is everywhere here. The community leaders do not protect us during the strikes. Some of the leaders are at the forefront of looting when strikes occur, so how can they help? The government must protect us from xenophobia and crime. The police need to do their work better because right now they are not (Interview with Somali refugee, 7 March 2016).

Inadequate police protection and failure to respond when refugee businesses are under attack deepens exposure to security risks. A Congolese refugee said that the only recourse available was to "run away" as the "police here in such instances, they don't protect us, but instead abuse us" (Interview with Congolese refugee, Cape Town, 5 March 2016). Others displayed similar distrust of the police because of perceptions of bias:

The police are not very helpful. If you have a case against a South African, they will always side with the South African. So, it's a waste of time to report a case against a South African (Interview with Congolese refugee, 24 February 2016).

How accurate are these perceptions of South African hostility towards refugee businesses and business-owners? A 2010 SAMP national survey of South African citizens found that only 20% were in favour of making it easier for migrants to establish small businesses and for migrant traders to buy and sell. Only 25% felt that refugees should be allowed to work in South Africa. A similar proportion said they would take part in actions to prevent migrants from operating a business in their neighbourhood, 15% said they would combine with others to force migrants to leave and 11% said they were prepared to use violence against them. Over 55% agreed with the proposition that the reason why migrants were victims of violence was because they did not belong in South Africa. Only 36% said that refugees should always enjoy police protection and 25% that they should never enjoy protection (Crush et al., 2013: 32-38).

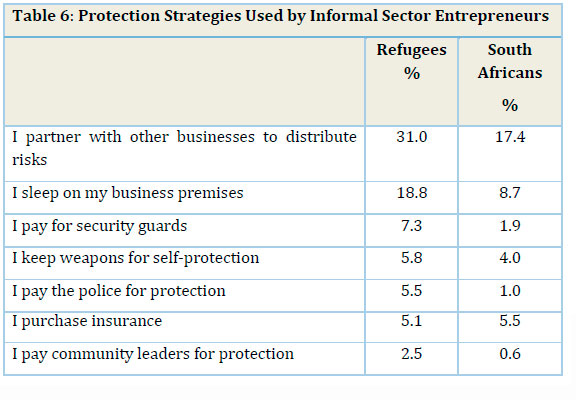

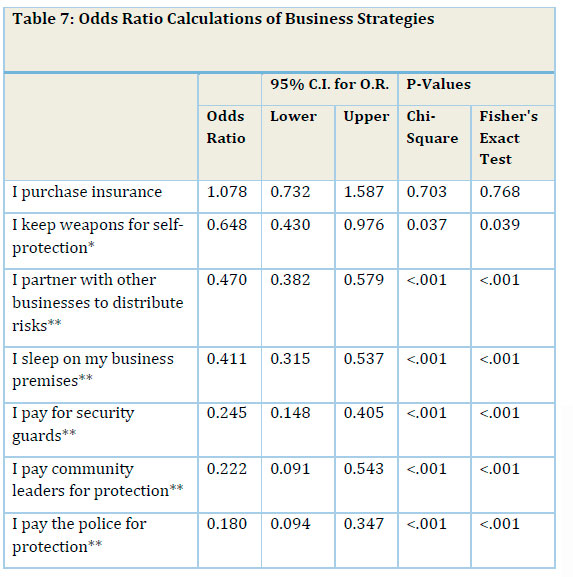

A number of studies have suggested that to lower the risks of victimisation, migrants adopt various measures to protect themselves and their employees (Gastrow, 2013; Hikam, 2011; Gastrow & Amit, 2015; Smit & Rugunanan, 2014). This survey sought to establish how common some of these strategies actually are and whether they are also adopted by South Africans (Table 6). One of the most common strategies is risk-sharing by partnering with other businesses. Nearly one-third of refugees and 17% of South Africans adopt risk-sharing through partnership. Sleeping on business premises (often a modified container) is a strategy pursued by both groups but, again, by more refugees (19% versus 9% of South Africans). There have been several high-profile shootings of robbers by refugees under attack but this survey found that only 6% keep weapons for self-protection. Other strategies (pursued by less than 10% of refugees and 5% of South Africans) include paying security guards and paying protection money to the police or community leaders. Around 5% of both groups purchase insurance. Table 7 analyses if the differences between the refugees and South Africans are statistically significant. With the exception of paying for insurance, refugees were far more likely than South Africans to adopt strategies of self-protection. Refugees were five times as likely to pay for protection and twice as likely to sleep on their business premises and to partner with others to distribute risk.

Various other strategies emerged in the course of the in-depth interviews although it is not known how common these are. For example, some refugees said that they like to hire South Africans to assist in communication with customers and also because it reduces their vulnerability to violence. In addition to paying protection money to police and community leaders, refugees in one part of Cape Town pay regular protection money to the local taxi association. The taxi association then uses this reality to extort money from South Africans in the area as well. Others make sure that they do not keep all their stock on the business premises out of fear that they will be cleaned out during looting or confiscation of goods by the police. Still others are only open for business when they know that the police are no longer patrolling.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have undertaken a comparative risks assessment and vulnerabilities analysis for refugee and South African entrepreneurs operating small business ventures in the informal economies of Cape Town city and various towns of Limpopo Province. Our results show that while both groups are exposed to several risks concurrently, refugee enterprises are far more vulnerable and overexposed. The social and structural insecurity experienced by refugee entrepreneurs is unambiguous from several key findings. Despite operating in the same localised environment and under similar conditions, this group encounters a more challenging set of hurdles and on a more frequent basis. The general act of operating small businesses in the informal economic sector does make business owners of all kinds vulnerable, but this alone cannot explain the greater vulnerabilities of the refugee cohort. Instead, xenophobia and refugee business owners' status as 'outsiders' adds another layer of risk for these operators. Limited access to police protection and mistreatment by them only exacerbates this insecurity.

What is also evident from our research and other recent studies is that the majority of refugee operators have not, to date, been affected by a range of potential risks. In part, this may be because of the mitigation strategies they adopt. As refugee and migrant communities grow in South Africa, the emergence of some individuals who are successfully able to mitigate common risks and build their enterprises is to be expected. However, rather than treating these achievements with suspicion and negativity, as the official mind tends to do, greater attempts need to be made to harness these productive capacities for the growth of local informal, entrepreneurial economies. These abilities are not an abnormal development nor are they driven largely or entirely by unfair advantages or the use of illicit practices. Ultimately, comprehensive national and localised strategies are required to develop and support informal entrepreneurship and small business growth in South Africa. In this process, both citizen-operated and refugee enterprises must be crucial stakeholders, and not written-off as insignificant, unequal or illegal.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the UNHCR Geneva for funding the Refugee Economic Impacts SAMP research project on which this paper is based.

References

Abor, J. and Quartey, P. 2010. Issues in SME development in Ghana and South Africa. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 39: 218-228. [ Links ]

Bekker, S. 2015. Violent xenophobic episodes in South Africa, 2008 and 2015. African Human Mobility Review, 1: 229-252. [ Links ]

Callaghan, C. and Venter, R. 2011. An investigation of the entrepreneurial orientation, context and entrepreneurial performance of inner-city Johannesburg street traders. Southern African Business Review, 15: 28-48. [ Links ]

Charman, A. and Piper, L. 2012. Xenophobia, criminality and violent entrepreneurship: Violence against Somali shopkeepers in Delft South, Cape Town, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 43: 81-105. [ Links ]

Charman, A., Petersen, L. and Piper, L. 2012. From local survivalism to foreign entrepreneurship: The transformation of the spaza sector in Delft, Cape Town. Transformation, 78: 47-73. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2014. Xenophobic Violence in South Africa: Denialism, Minimalism, Realism. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 66, Cape Town and Waterloo: Southern African Migration Programme. [ Links ]

Crush, J. and Ramachandran, S. 2015a. Doing business with xenophobia. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Cape Town and Ottawa: SAMP and IDRC, pp. 25-59. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). 2015. Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Cape Town and Ottawa: SAMP and IDRC. [ Links ]

Crush, J., Ramachandran, S. and Pendleton, W. 2013. Soft Targets: Xenophobia, Public Violence and Changing Attitudes to Migrants in South Africa After May 2008. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 64, Cape Town: Southern African Migration Programme. [ Links ]

Davis, G. 2015. Attacks on Migrants Due to Their Socio-Economic Impact. Eyewitness News. November 10, 2015.

Gastrow, V. 2013. Business robbery, the foreign trader and the small shop: How business robberies affect Somali traders in the Western Cape. SA Crime Quarterly, 43: 5-15. [ Links ]

Gastrow, V. and Amit, R. 2015. The role of migrant traders in local economies: A case study of Somali spaza shops in Cape Town. In: Crush, J., Chikanda, A. and Skinner, C. (Eds.). Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa. Cape Town and Ottawa: SAMP and IDRC. [ Links ]

Gov.za. 2015. Operation Fiela. From <http://www.gov.za/operation-fiela>.

Grant, R. 2013. Gendered spaces of informal entrepreneurship in Soweto, South Africa. Urban Geography, 34: 86-108. [ Links ]

Hikam, A. 2011. An Exploratory Study on the Somali Immigrants' Involvement in the Informal Economy of Nelson Mandela Bay. MA Thesis. Port Elizabeth: Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University. [ Links ]

Jordaan, N. 2015. Operation Fiela 'Demoralizes and Dehumanizes' Migrants. Sunday Times, July 22, 2015.

LHR (Lawyers for Human Rights). 2015. Civil Society Organizations Address Media on the Ongoing Raids Targeting Foreign Nationals. From http://bit.ly/2eKJODO.

Ligthelm, A. 2011. Survival analysis of small informal businesses in South Africa, 2007-2010. Eurasian Business Review, 1: 160-179. [ Links ]

Masinga, L. 2015. Stop Using the Word Xenophobia. Independent Online, July 10, 2015.

Misago, J-P. 2016. Responding to xenophobic violence in post-apartheid South Africa: Barking up the wrong tree. African Human Mobility Review, 2: 443-467. [ Links ]

Nicolson, G. 2015a. Operation Fiela: Thousands of Arrests, Doubtful Impact. Daily Maverick, September 8, 2015.

Nicolson, G. 2015b. Parliamentary Report on Xenophobic Violence Talks a Lot, Says Very Little. Daily Maverick, November 24, 2015.

Peberdy, S. 2017. Competition or Cooperation? South African and Migrant Entrepreneurs in Johannesburg. SAMP Migration Policy Series No. 75, Waterloo and Cape Town: Southern African Migration Programme. [ Links ]

PMG (Parliamentary Monitoring Group). 2015. Meeting to Adopt Ad Hoc Joint Committee on Probing Violence Against Foreign Nationals Report. Cape Town: South African Parliament. [ Links ]

Piper, L. and Charman, A. 2016. Xenophobia, price competition and violence in the spaza sector in South Africa. African Human Mobility Review, 2: 332-361. [ Links ]

PJC (Parliamentary Joint Committee). 2015. Report of the Ad Hoc Joint Committee on Probing Violence Against Foreign Nationals. Cape Town: South African Parliament. [ Links ]

Rogerson, C. 2016a. Progressive rhetoric, ambiguous policy pathways: Street trading in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa. Local Economy, 31: 204-218. [ Links ]

Rogerson, C. 2016b. South Africa's informal economy: Reframing debates in national policy. Local Economy, 31: 172-86. [ Links ]

Skinner, C. 2008. The struggle for the streets: Processes of exclusion and inclusion of street traders in Durban, South Africa. Development Southern Africa, 25: 227-242. [ Links ]

Smit, R. and Rugunanan, P. 2014. From precarious lives to precarious work: The dilemma facing refugees in Gauteng, South Africa. South African Review of Sociology, 45: 4-26. [ Links ]

SRG (Special Reference Group). 2015. Report of the Special Reference Group on Migration and Community Integration in KwaZulu-Natal. Pietermaritzburg: Provincial Government of KwaZulu-Natal. From <http://bit.ly/2uVTL7G> [ Links ].

Supreme Court. 2014. Somali Association of South Africa v Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (48/2014). ZASCA 143 (September 26, 2014).

Thompson, D. 2016. Risky business and geography of refugee capitalism in the Somali migrant economy of Gauteng, South Africa. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42: 120-35. [ Links ]

Willemse, L. 2011. Opportunities and constraints facing informal traders: Evidence from four South African cities. Town and Regional Planning, 59: 8-16. [ Links ]

Williams, P. 2015. 'Minister Jeff Radebe: Inter-Ministerial Committee on Migration. From http://bit.ly/2ux1VBb.

Venter, R. 2012. Entrepreneurial values, hybridity and entrepreneurial capital: Insights from Johannesburg's informal sector. Development Southern Africa, 29: 225-239. [ Links ]