Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Old Testament Essays

versão On-line ISSN 2312-3621versão impressa ISSN 1010-9919

Old testam. essays vol.36 no.2 Pretoria 2023

https://doi.org/10.17159/2312-3621/2023/V36N2A12

ARTICLES

Locust and Armies in Joel 1-2: One More Possible Scenario

Felix Poniatowski

Adventist University of Africa, Nairobi

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to analyse the descriptions of the locust (Joel 1) and the approaching army (Joel 2) in an attempt to reconstruct the scenario of events that could explain the maximum details of the text. Usually, scholars identify the locust and the army based on an assumed date of the book's composition. This article suggests a different approach: first to identify the characters of Joel 1 and 2 based on the thorough analysis of the text and reconstruct the possible scenario of the events, before trying to define with which time frame this scenario better fits. The analysis arrived at the following conclusions: the author deliberately portrays the invasion of the locust (Joel 1) and the approaching army (Joel 2) as two events of a similar significance, scope and consequences. Both, the locust attack and the approaching army should be interpreted as pointing to the military vents. The description of the locust invasion is used as a metaphor for the destruction of the Northern Kingdom by Assyria. The prophet invites the population of Judah to wail over the destruction of the sister-state but no one heeded the prophet's invitation. Then Joel announces another calamity (Joel 2) that will hit Judah if the people do not repent.

Keywords: Book of Joel, date of Joel, locust invasion, fall of Samaria, Assyrian invasion, scenario of the events.

A INTRODUCTION

In biblical studies, interpretation may be compared to solving an equation with many variables. Such an equation could have many possible solutions. To find the value of one variable, one usually hypothesises about the values of all the others. The best example is the date of composition. There are ongoing and endless debates about the time settings of almost every biblical book and if a book is placed within a particular time frame, it will definitely affect many issues about its interpretation, such as the addressee, purpose of the author, theology, etc.

I assume this is exactly the case with the book of Joel. There are so many variables with different possible meanings in this book. The date of composition is one of them.1 Other debated issues are: 1) how to interpret the description of the locust in Joel 1-is it the depiction of a natural disaster or a metaphor of army invasion? 2) A similar question about the description of the army in Joel 2, is it a real army, an apocalyptic army or a metaphor for locust attack? 3) What is the relationship between Joel 1 and 2-is it a description of the same event or of different events? In an attempt to answer these questions, scholars have suggested different scenarios in Joel 1-2. However, none of the scenarios can explain all the details of the text. These scenarios and the arguments pro and contra may be summarised as follow:

First, Joel 1 and 2 contain a description of two subsequent locust attacks2 or of a single locust invasion that occurred in two stages: the initial stage (Joel 1) when the insects attacked the country and the second stage when the new progeny of insects appeared and caused even greater damage (Joel 2).3 This hypothesis explains many similarities between the accounts of the locust invasion in Joel 1 and the approaching army in Joel 2. However, it downplays the role of military language and imagery that predominates in Joel 2. Furthermore, the reference to the "northerner" (Joel 2:20) does not fit the description of the locust and implies the military threat.

Second, Joel 1 and 2 contain a parallel account of the same locust invasion.4 The objections against the previous theory might be applied to this one as well. It is important also to note that this hypothesis fails to provide a sufficient explanation for the employment of different forms of verbs for the description of the events in Joel 1 and 2. While in Joel 1, the verbs in the perfect form predominate, implying a past event, the account of Joel 2 is constructed with the verbs of the imperfect forms, which indicates a future event. This argument leads to the conclusion that not one but two events are in view.

Third, locust in the book of Joel is just a metaphor for the human army. The real army is implied in both Joel 1 and 2.5 According to Douglas Stuart, who advocates this idea, Joel 1:1-2:17 describes the same event-one Day of YHWH.6 Although Stuart is very reluctant to date the composition of the book, he mentions three possible occasions when the speeches of Joel might be pronounced, namely "the Assyrian invasion of 701 B.C., the Babylonian invasion of 598, or the Babylonian invasion of 588."7 However, if one considers two different forms of verbs employed in the accounts of Joel 1 and 2, then it would imply that the prophet had in mind two completely different devastating military attacks, the notion that Stuart does not address in his commentary.

Fourth, Joel 1 contains the description of a locust attack while Joel 2 describes the invasion of an apocalyptic army.8 This idea was brought forward by Hans Walter Wolff. The strong point of this hypothesis is that it tries to explain the extraordinary abilities of the invaders (Joel 2:1-11) and the cosmic events (Joel 2:10) that can be associated neither with locust nor with a human army. However, this theory does not have many adherents. First of all, it should be noted that the description of the apocalyptic army is not placed in an eschatological context as should be expected. Extraordinary phenomena are often included in the description of the Day of the Lord, but it does not necessarily imply apocalyptic elements (cf. Isa 13; Hab 3:11).

Fifth, the disaster described by Joel was not real but the author created "a literary world of calamities to serve as metaphors describing the character of the Day of the Lord" (emphasis in the original).9 This is a very radical point of view. On the one hand, it seeks to explain the exaggerated language employed to describe the invaders in Joel 1 and 2 but by solving one problem, it creates another one. It does not make sense to call the people to active action if the calamity is not real but existed only in the prophet's imagination.

Continuing the metaphor of equation, the identity of the locust and the army may be presented as two variables, which in turn depend on another variable, namely the date of the book's composition. If the book is placed in a certain historical period, then the historical situation will dictate what answer is preferable. For example, those scholars who advocate the postexilic origin of the book usually do not favour the option of identifying the invaders of Joel 2:1-11 as a real army and tend to treat the enigmatic intruders of Joel 2 as another metaphorical depiction of the locust.10 Such a position is explicable-in the postexilic period, Judah did not experience a serious military threat and the assumption that the prophet implies a real army does not make much sense. However, the scholars who prefer to locate the book of Joel in the pre-exilic settings usually see in the invaders of Joel 1 and 2 a reference to the real military threat.11 Of course, it is logical to establish first the historical background and then to interpret the book in light of certain historical settings. Such a line of argumentation would not be a problem had the dating of the book been a certain matter but the question of the time of the composition of Joel is very obscure.12

As has been shown above, most scholars interpret the locust and the army based on the date of the book's composition. This article suggests another approach. What if one tries to do the opposite? First, it is important to identify what the author meant by the locust and the army, taking into account all the details of the text and reconstructing the possible scenario of the events; and only after that define what historical settings fit the scenario the best.

B DESCRIPTION OF THE LOCUST (JOEL 1:2-20)

1 Arguments in favour of the literal locust invasion

Calamities such as insect infestation were not unusual in ancient times. Except for the references to the locust in the Hebrew Bible (Deut 28:38; 1 Kgs 8:37; Nah 3:15, 17), there are a number of other ancient documents that witness people's struggle with similar disasters. Thus, the extant correspondence between the office of the Assyrian king and the governors of the provinces (eighth century B.C.E.) demonstrates that the locust was considered a serious threat to the welfare of the Empire.13 One letter even describes how the people of one of the provinces fought against the locust attack.14 Locust also was often mentioned in the suzerain treaties as a curse that was invoked upon the parties in case they broke the alliance.15 The abovementioned examples demonstrate that the locust infestation which is described in the book of Joel was not unusual to the Israelites.

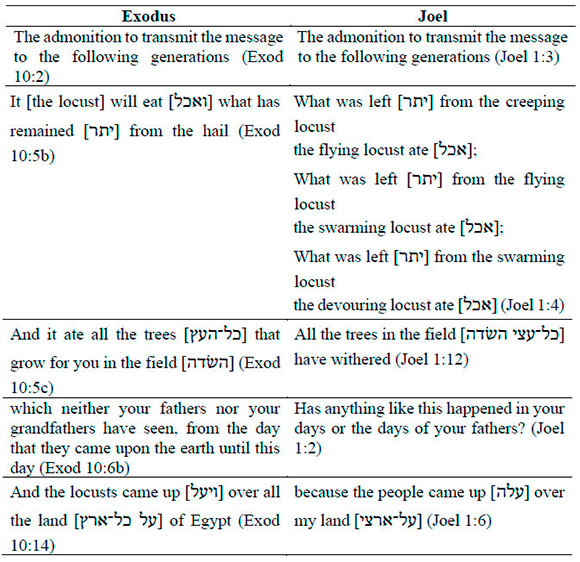

Many details in the text support the idea that the locust invasion of Joel 1 was a literal disaster. The following arguments can be mentioned in favour of this interpretation. The author provides a very detailed and vivid description of the calamity. He mentions the withered trees (Joel 1:12), the perished crops in the field (Joel 1:11), the shortage of supplies in the Temple (Joel 1:9, 14) and even the suffering of the wild animals (Joel 1:18-20). Furthermore, the numerous parallels with the locust plague in Egypt also support the idea that the locust invasion was literal:

Joel portrays the locust infestation against the background of the eighth plague of Egypt. First of all, by doing this the author emphasises that the Lord stands behind the disaster. However, the comparison of the calamity with the Egyptian plague has one more important implication. The author does not need to allude to the Exodus narrative to show that the Lord sent the locust. For this purpose, he could just portray the insect invasion as the fulfilment of the curses of the covenant (Deut 28:38). The covenant curses were intended to correct the nation if the people turned away from the Lord. The reference to the plague of Egypt implies more than just a correction of the nation. In Egypt, the Lord waged a war against Pharaoh using plagues and apparently by alluding to the Exodus narrative Joel conveys the same message-the Lord started a war against his people.

2 Arguments against the literal locust invasion

Although the vivid and detailed description of the locust attack could be an argument in favour of the literal interpretation, the scope of the depicted disaster could undermine this assurance. A calamity like this must have tremendous consequences. Without any doubt, it should be accompanied by a very severe famine, mass starvation and thousands of deaths. Furthermore, according to the book of Joel, the locust invasion was followed by drought (Joel 1:19-20), which made the disaster even more terrible.16 Most probably, it required a couple of years to restore the economy of the region after such a devastation. The description of the disaster seems very much exaggerated. The prophet portrays the locust invasion as an attack of four different insects17 that came to the land one after another and devoured all vegetation. The threefold repetition that the remainder from the attack of one insect was devoured by another (Joel 1:4) has a rhetorical effect and indicates that there was nothing left behind after the locust attack. It is not surprising that some scholars doubt that a disaster of such scope took place. For example, Ferdinand E. Deist points out that it was hardly possible that the locust infestation and the drought happened together.18 As mentioned earlier, Deist assumes that in reality, there was neither a locust attack nor drought, but the disaster existed only in the author's imagination.19

Another fact that against the literal interpretation of the locust in Joel 1 is the reference to locust as a "nation" [Heb.  ] (Joel 1:6). The same word is consistently used in the book of Joel for the description of the foreign nations that terrify Judah (Joel 2:17, 19; 4[3]:2, 8). Furthermore, the locust is depicted as "strong" and "numerous" people (Joel 1:6); the dwellers of Canaan were depicted in the same manner (Deut 4:38; 7:1; 9:1). All those details favour the interpretation of the locust as metaphor for a real army. Moreover, as Stuart points out, the teeth/lion comparison could hardly correspond to the description of the locust and is usually employed to depict the people (Ps 58:6; Prov 30:14).20

] (Joel 1:6). The same word is consistently used in the book of Joel for the description of the foreign nations that terrify Judah (Joel 2:17, 19; 4[3]:2, 8). Furthermore, the locust is depicted as "strong" and "numerous" people (Joel 1:6); the dwellers of Canaan were depicted in the same manner (Deut 4:38; 7:1; 9:1). All those details favour the interpretation of the locust as metaphor for a real army. Moreover, as Stuart points out, the teeth/lion comparison could hardly correspond to the description of the locust and is usually employed to depict the people (Ps 58:6; Prov 30:14).20

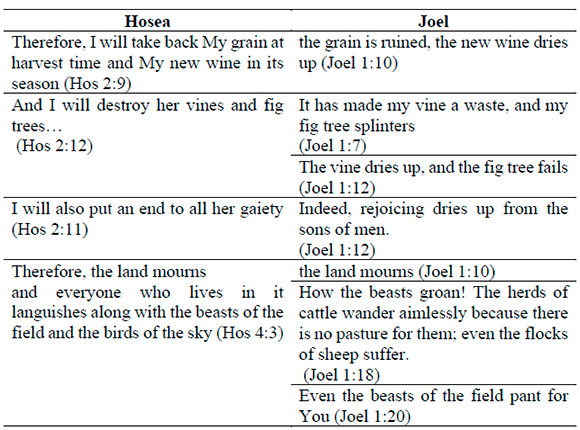

It is also worth mentioning that there are some striking parallels between the book of Joel and the book of Hosea. Joel describes the locust invasion in terms similar to the description of God's punishment over Israel in the book of Hosea.

Those parallels could hardly be a coincidence. Furthermore, it appears that Joel also uses other motifs from the book of Hosea. Thus, the author of Joel pays special attention to the priests. He mentions them three times (Joel 1:9, 13; 2:17) and gives them a special role in the organisation of the communal lament. In other words, the priests are responsible for the spiritual condition of the nation. Hosea also emphasises the role of the priests (Hos 4:6; 5:1; 6:9) and blames them and other leaders for the spiritual downfall of the nation (Hos 4:4; 5:1).21 Hosea also asks that the priestly office be withdrawn from them (Hos 4:6) and in the book of Joel, the priestly office is also compromised due to the lack of supplies (Joel 1:9, 13, 16).

Although the ruin of the Northern Kingdom was performed through the military invasion of Assyria, Hosea describes it rather as an agricultural disaster. Without any doubt, this description is metaphorical. If Joel draws on the book of Hosea, then it is possible that he portrays the military attack in terms of a natural disaster.

Both arguments are appealing, therefore, it is difficult to make a certain conclusion based on them. It seems that the author intentionally allows ambiguity to keep the intrigue and to make the description of the locust attack universally applicable to either a natural disaster or a military threat.

C DESCRIPTION OF THE ARMY (JOEL 2:1-11)

1 Arguments for a metaphorical description of the army (army=locust)

The description of the approaching army is ambiguous. Although the prophet extensively employs military terminology, there are several details in the text that do not allow straightforward conclusions.

On the one hand, the passage contains several features that suggest that the "army" is a metaphor for locust. Thus, the invaders are presented as very well organised (Joel 2:7-8; cf. Prov 30:27)-they penetrate the houses through the windows (Joel 2:9) and they produce a sound ("crackling of a flame of fire," Joel 2:5), which is very similar to the sound that the swarm of locust makes while eating the vegetation. Furthermore, it was noted that since in Joel 2:4, the invaders are compared to the horses and the riders, they cannot be the real army.22Another argument that is often mentioned to support this view is the resemblance of the locust and the horses. As Crenshaw points out, even in some modern languages, the word "locust" means "a small horse."23 In the Bible, the locust and horses are sometimes compared to each other (Job 39:20; Rev 9:7). Therefore, if the real locust is in view, then the comparison with the horse (Joel 2:4) seems reasonable.

2 Arguments in support of the description of a real army

On the other hand, some details might be used to prove that the army of Joel 2 is not the locust. First of all, we need to consider that Joel 2:1-11 describes the siege of the city and it does not make much sense to compare the locust with an army that attacks the fortification. The insects can hit the fields and gardens but not the city. Moreover, the notion that the invaders fell on swords and remained alive (Joel 2:8) could hardly be applied to the locust. The invaders are so powerful that they produce cosmic anomalies (Joel 2:10), which locusts cannot do. Finally, the invaders are called "northerner" (Joel 2:20) and usually, from the north, all the enemies came to Israel. Therefore, the "northerner" must be associated with a military threat.

As many scholars have observed also,24 the account of Joel 2 shares many common ideas with Isa 13. Isaiah also calls on people to wail as they await the approaching Day of the Lord (Isa 13:6). He describes an army coming from the mountains (Isa 13:4). The army is prepared for the battle by the Lord himself (Isa 13:3). The author compares the sound of the approaching invaders with the noise of many people (Isa 13:4) and finally, Isaiah mentions cosmic events such as the darkening of the sun, moon, and stars (Isa 13:10). The question of the identity of the army in Isa 13 is difficult to ascertain. Scholars usually either interpret it as a heavenly army25 or try to find an appropriate earthly candidate who fit the description the best.26 In any case, the main concern of the account of Isa 13 is a military threat.27 Therefore, those parallels could be an additional argument in favour of interpreting the approaching army of Joel 2 as an army but not as a locust.

As in the case of Joel 1, it is very difficult to support one position against another. Without any doubt, the author intentionally portrays the disaster of Joel 2 as similar to that of Joel 1.28 On the one hand, the prophet saturates the description of the invaders in military tones but he leaves many details that allow drawing parallels with the locust.

D OTHER OBSERVATIONS

1 Similar nature of events

Although it is difficult to make a certain conclusion about the identity of the army and the locust, some important observations are in order here. It seems the author intentionally creates several parallels between the description of the army and the locust. Both accounts start similarly, employing the imperatives and urging people to do something to cope with the disaster (Joel 1:13-14; 2:12-13). In both cases, the author addresses "all dwellers of the earth" (Joel 2:1; 1:2); the enigmatic army is presented as a sign of the approaching Day of the Lord as well as the locust invasion (Joel 2:1; cf. 1:15). Furthermore, both the locust in Joel 1 and the army in Joel 2 turn the land into burnt wilderness (Joel 1:18-20; cf. Joel 2:3). The army is described as an extremely unique people that have not been known from eternity and will never be known again (Joel 2:2). The locust invasion of Joel 1 is also presented as an extraordinary event (Joel 1:2). Furthermore, both chapters elaborate on the idea that the Lord wages a war against his people. If in Joel 1 this idea was emphasised through the reference to the Exodus motif, in Joel 2, it was expressed explicitly by portraying the Lord as the head of the army that is about to devastate Judah. Those similarities imply that the coming disaster of Joel 2 is of the same or similar nature as the previous one.

2 Two events or one?

This question was already partially addressed in the introduction. As already mentioned, the employment of different verb tenses in Joel 1 and 2 is a strong argument to support the idea that two events are in view. Furthermore, even the content of the two chapters implies different occasions. Thus, in Joel 1, the prophet calls people to participate in a lament for the disaster that had already occurred but in Joel 2, he again calls the people for a communal lament but in this case to avert the approaching disaster (Joel 2:14). This observation leads to the conclusion that the author refers to two different events of a similar nature. One is the complete devastation of the land in the past and another is a similar event that would happen in the future.

3 The people's response

A calamity such as the one described in Joel 1 is expected to provoke reaction in the society. However, it is surprising that the author says nothing about the people's response. He invites the population to the communal lament and mentions that even the beasts of the field weep and wail (Joel 1:18-20) but he says nothing about the people's participation. This silence is intriguing.29Usually, people are very responsive when they experience a disaster in their life. It was a common practice among the ancient people to seek support from the divine in times of trouble.

E POSSIBLE SCENARIO OF THE EVENTS

As shown above, Joel portrays the locust invasion and the approaching of the Lord's army as two events of the same tremendous significance. Therefore, it is possible to assume that he implies either two natural disasters or two military catastrophes. There are several arguments against the hypothesis of two locust attacks: it does not explain an extensive use of the military language and imagery. It does not provide a sufficient interpretation for the term "northerner" (Joel 2:20). A locust attack, even the worst one, could hardly be a topic to remember in the following generations (Joel 1:3). Finally, the Day of the Lord theme implies the context of the final judgment, which could hardly apply to the locust invasion.

Furthermore, the natural catastrophe is not comparable to the military threat. The ancient people comprehended a war as the most dangerous thing that could ever happen. In the list of the covenant curses, war and exile are the ultimate punishments for the violation of loyalty. When David was advised to choose between different penalties for his sin, he chose, without doubting, the natural one (2 Sam 24:12-14). This fear of war can be easily explained. Any natural disaster, although could result in severe damages and losses, was just a temporary problem. Even in the worst of calamities the region could recover from the consequences in several years but the war could result in a permanent problem. Sometimes, wars erased whole nations from the map of history.

If we assume that the author of the book had in mind two military catastrophes, then it becomes necessary to seek a link to the historical events which they symbolise. In this case, people's indifference regarding the disaster might be a crux interpretum. The indifferent behaviour is possible only if the calamity is not too serious or if it does not affect the people directly. However, the first option is hardly probable because the prophet portrays the disaster as an extraordinary event. The catastrophe might not touch the hearts of the people if it happened not in their land but elsewhere. By default, it is generally assumed that the "locust attack" took place in Judah. However, in the first chapter of the book, there are no geographical references. The prophet indeed calls the people of Judah to mourn but the location of the disaster is not defined. On the other hand, as we have seen, the prophet portrays the consequences of the locust infestation just as Hosea portrayed the judgment over the Northern Kingdom. Therefore, it is probable that the author uses locust imagery to describe the fall of the Northern Kingdom. In this case, he invites the people of Judah to perform a lamentation over the sister-state. Such a lamentation is not a strange idea in the Hebrew Bible and ANE. Another prophet, Micah, expressed a similar lamentation (Mic 1:8-9) on the same occasion. We can find many examples of lamentation over the downfall and destruction of the city-states which once were mighty among other nations.30

The absence of the reaction of the population to the prophet's summons to participate in the lamentation over the downfall of the Northern Kingdom may be explained by the hostility that existed between Judah and Israel, especially in the last decades before the fall of Samaria. The coalition of the king of Syria and Israel attempted to force Ahaz, the king of Judah, to join them against the common enemy-Assyria. This political tension resulted in the so-called Syro-Ephraimite war (735-732 B.C.E.) when the army of the coalition besieged Jerusalem and Ahaz had to call the king of Assyria for help.

The main purpose of the author of the book of Joel was not only to organise the communal lament but also to warn the people of Judah that they would face the same destiny if they do not repent. In this case, the Day of the Lord that happened to Israel was a harbinger for another Day of the Lord for Judah. However, it looks like nobody responded to Joel's summon, and the prophet himself performed a lamentation (Joel 1:19). Then Joel announced another calamity that was only supposed to come. This time Joel indicated from the very beginning that the disaster would fall upon Zion (Joel 2:1).

The suggested scenario explains many details of the depicted disaster. If it were a literal locust attack, then it would be surprising that no records of such tremendous catastrophe have been preserved even though the prophet himself insisted on keeping the knowledge of it. Even if the people ignored the prophet's admonition to tell their children about the enormous disaster, the memory of it should be alive for decades or even more like, for example, a memory of the earthquake in times of Uzziah (Amos 1:1; Zech 14:5). However, if one admits that the prophet reflects on the destruction of the Northern Kingdom, then no question like this arises. The memory of the fall of Samaria was preserved and this event was intended to become a matter of rethinking for the sister-nation of Judah.

The locust invasion is a perfect metaphor for the fall of Israel. Joel portrays the land as completely devastated with nothing left in it. It is exactly what happened to the Northern Kingdom. Ten tribes of Israel assimilated with other nations and completely disappeared from world history.

The current hypothesis explains why the author so extensively uses military language and imagery. Apparently, Joel intentionally incorporates some elements which indicate the war-like event into the descriptions of the locust invasion (Joel 1:6). This detail helps the readers to understand that the locust symbolises a military attack. The mentioning of the "northerner" with the reference to the approaching army also perfectly fits the current picture. This scenario could have some important implications. If the locust infestation is a metaphor for the fall of the Northern Kingdom and the approaching army points to the threat of the destruction of Judah, then, most probably, the events in the book should be placed in the time range between the fall of Samaria (722 B.C.E.) and the destruction of Jerusalem (586 B.C.E.).

It is worth noting also that the proposed scenario explains the position of the book of Joel in the canon. The placement of the book between Hosea and Amos has always puzzled scholars. James Nogalski tries to explain it from the point of view of redaction criticism. According to him, the book of Joel was composed and placed in its current position at the very last stage of the editorial process of the Book of the Twelve.31 However, the hypothesis suggested in this article adds one more reason for placing the book of Joel in its current position. Three books (Hoses, Joel and Amos) deal with the question of the fall and destruction of the Northern Kingdom and the three also use the disaster that the Northern Kingdom faced as a warning for Judah.

F CONCLUDING REMARKS

This article is a kind of thought experiment. The conclusion is based on several assumptions and of course, the validity of the conclusion depends on the validity of the assumptions. Furthermore, to make different assumptions is to reach different conclusions. However, since there are many uncertain issues in the book of Joel, it is impossible to avoid a multiplicity of possible solutions. Probably, it was the intention of the author of the book to leave many things unsaid or ambiguous allowing different and sometimes contradictory interpretations. On account of what is said above, I do not suggest that the interpretation suggested in this article is the only true one but it is equally possible among all other suggested interpretations of the book's events.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Andersen, Francis I. and David Noel Freedman. Hosea. Anchor Bible 24; Garden City: Doubleday, 1980. [ Links ]

Barton, John. Joel and Obadiah: A Commentary. Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001. [ Links ]

Credner, K. A. Der Prophet Joel, Uebers und erklart. Halle, Germany, 1831. [ Links ]

Crenshaw, James L. Joel. Anchor Bible 24C. Garden City: Doubleday, 1995. [ Links ]

Deist, Ferdinand E. "Parallels and Reinterpretation in the Book of Joel: A Theology of the Yom Yahweh?" Pages 63-79 in Text and Context: Old Testament and Semitic Studies for F.C. Fensham. Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series 48. Edited by F. Charles Fensham and Walter Theophilus Claassen. Sheffield: JSOT, 1988. [ Links ]

Garrett, Duane A. Hosea, Joel. New American Commentary 19a. Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1997. [ Links ]

Gray, George Buchanan. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Isaiah, I-XXXIX. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1912. [ Links ]

Green, M. W. "The Uruk Lament." Journal of the American Oriental Society 104 (1984): 253-279. [ Links ]

Hayes, Katherine Murphey. The Earth Mourns: Prophetic Metaphor and Oral Aesthetic. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2002. [ Links ]

Kapelrud, Arvid S. Joel Studies. Uppsala: Almquist and Wiksells, 1948. [ Links ]

Linville, James R. "The Day of Yahweh and the Mourning of the Priests in Joel." Pages 98-113 in The Priests in the Prophets: The Portrayal of Priests, Prophets, and Hearing the Book of the Twelve (ed. James Nogalski and Marvin A. Sweeney ed.; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000), 94-95. Other Religious Specialists in the Latter Prophets. Edited by Lester L. Grabbe and Alice Ogden Bellis. London: T&T Clark, 2004. [ Links ]

Nogalski, James D. "Intertextuality in the Twelve." Pages 102-25 in Forming Prophetic Literature: Essays on Isaiah and the Twelve in Honor of John D.W. Watts. Edited by James W. Watts and Paul R. House. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996. [ Links ]

_______________________. "Joel as 'Literary Anchor' for the Book of the Twelve." Pages 91-109 in Reading and Hearing the Book of the Twelve. Edited by James Nogalski and Marvin A. Sweeney. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2000. [ Links ]

_______________________. Redactional Processes in the Book of the Twelve. Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 105. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1993. [ Links ]

Parpola, Simo. The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part I: Letters from Assyria and the West. State Archives of Assyria I. Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1987. [ Links ]

Prinsloo, Willem S. The Theology of the Book of Joel. Berlin: De Gruyter, 1985. [ Links ]

Simkins, Ronald A. "God, History, and the Natural World in the Book of Joel." Catholic Biblical Quarterly 55 (1993): 435-452. [ Links ]

Smith, Gary V. Isaiah 1-39. New American Commentary 15a. Nashville: B & H Publishing Group, 2007. [ Links ]

Strazicich, John. Joel's Use of Scripture and Scripture's Use of Joel: Appropriation and Resignification in Second Temple Judaism and Early Christianity. Leiden: Brill, 2007. [ Links ]

Stuart, Douglas. Hosea-Jonah. Word Biblical Commentary 31. Dallas: Word Inc., 2002. [ Links ]

Sweeney, Marvine A. The Twelve Prophets. Vol. 1 of The Twelve Prophets. Berit Olam. Edited by David W. Cotter. Collegeville: Liturgical, 2000. [ Links ]

Wolff, Hans W. Joel and Amos. Translated by W. Janzen, S. Dean McBride, Jr., and C. A. Muenchow. Hermeneia. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977. [ Links ]

Submitted: 02/09/2022

Peer-reviewed: 29/03/2023

Accepted: 10/04/2023

Felix Poniatowski, Adventist University of Africa, Nairobi, Kenya. Email: poniatowskif@aua.ac.ke. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6541-105X.

1 Usually, the book is considered a post-exilic composition. See Leslie C. Allen, The Books of Joel, Obadiah, Jonah, andMicah (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1976), 19-25; Gosta W. Ahlström, Joel and the Temple Cult of Jerusalem (VTSup 21; Leiden: Brill, 1971), 129; Hans W. Wolff, Joel and Amos (trans. Waldemar Janzen, S. Dean McBride, Jr., and C. A. Muenchow; Hermeneia; Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977), 5 However, other possible options for dating are advocated by scholars. For example, Marvin A. Sweeney, The Twelve Prophets: Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah [vol. 1 of The Twelve Prophets; Berit Olam; ed. David W. Cotter; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2000], 150), favours a pre-exilic dating. Elie Assis advocates the exilic date of composition (see Elie Assis, "The Date and the Meaning of the Book of Joel," VT 61 [2011]: 168-69). Many scholars are very cautious about the date of composition of Joel. For example, Douglas Stuart says, "Ultimately, however, any dating of the book of Joel can be only inferential and speculative" (Douglas Stuart, Hosea-Jonah [WBC 31; Waco: Word Books, 1987], 226); Duane Garret conveys almost the same idea, "Any suggested time frame for the book should be tentative, and the interpretation of the book should not depend upon a hypothetical historical setting"; Duane A. Garret, Hosea, Joel, (NAC 19a; Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1997), 294.

2 Ronald A. Simkins, "God, History, and the Natural World in the Book of Joel," CBQ 55 (1993): 443-444.

3 James L. Crenshaw, Joel (AB 24C; New York: Doubleday, 1995), 122.

4 John Barton, Joel and Obadiah: A Commentary (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 47, 69.

5 Stuart, Hosea-Jonah, 23 2-33.

6 Ibid., 231.

7 Ibid., 226.

8 Wolff, Joel and Amos, 42.

9 Ferdinand E. Deist, "Parallels and Reinterpretation in the Book of Joel: A Theology of the Yom Yahweh?" in Text and Context: Old Testament and Semitic Studies for F.C. Fensham (JSOTSup 48; ed. F. Charles Fensham and Walter Theophilus Claassen; Sheffield: JSOT, 1988), 64. Although he admits that a real catastrophe might have taken place, Linville agrees with Deist that the description of the disaster is rather fictional than real: "Perhaps the prophet Joel did have some real-world catastrophe in mind, but the book presents a literary world, and it is only to the latter world that the modern critic has any direct access." See James R. Linville, "The Day of Yahweh and the Mourning of the Priests in Joel," in The Priests in the Prophets: The Portrayal of Priests, Prophets, and Other Religious Specialists in the Latter Prophets (ed. Lester L. Grabbe and Alice Ogden Bellis; London: T&T Clark, 2004), 100.

10 Barton, Joel and Obadiah, 47, 69; cf. W. Prinsloo, The Theology of the Book of Joel (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1985), 42; Simkins, "God, History, and the Natural World," 443444.

11 See, for example, Stuart, Hosea-Jonah, 241; Sweeney, The Twelve Prophets, 151. As an exception, Arvid S. Kapelrud who dates the book of Joel to the pre-exilic period, argues that Joel 2 is also a presentation of the locust invasion; A. S. Kapelrud, Joel Studies (Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksells, 1948), 76.

12 In this regard, the statement made by Crenshaw is very illustrative: "To some extent such endeavors to establish a historical context for a biblical book constitute exercises in futility. Much of the argument moves in the realm of probability, often resting on one hypothesis after another about the development of the language and religion of the Bible." See Crenshaw, Joel, 28. See also fn. 1.

13 Simo Parpola, The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part I: Letters from Assyria and the West (State Archives of Assyria I; Helsinki: Helsinki University Press, 1987), 8687.

14 The letter of the province Lower Khabur contains a report of the fulfilment of the order from the Palace to kill the locust. The author of the letter says: "When they were few, we collected them ... pushed them into a seah measure and measured them with it; when they became oppressing, we just killed them in the middle of the field." Parpola, The Correspondence of Sargon II, 170-171.

15 See, for example, "The Vassal-Treaties of Esarhaddon," trans. D. J. Wiseman (ANET, 538) or "The Treaty between KTK and Arpad," trans. F. Rosenthal (ANET, 659).

16 The text of Joel 1:15-20 was differently interpreted. Typically, the words "flame" and "fire" in those verses are treated either as a metaphor for locust (Garrett, Hosea, Joel, 330) or as a reference to a severe drought that followed the locust invasion (Wolff, Joel and Amos, 13; Crenshaw, Joel, 50). There was also an idea that the effect of burnt land might be produced by the combination of the locust attack and a dry Palestinian summer (Simkins, "God, History, and the Natural World," 442.).

17 Alternatively, as Credner assumed, the four terms employed in Joel 1:4 correspond to the four different stages of the locust's life cycle. In this case, it could be that there was a single attack of the locust that produced a progeny that continued to multiply and devastate the land. See K. A. Credner, Der Prophet Joel, Uebers und erklart (Halle, Germany, 1831), 295. See also Wolff, Joel and Amos, 27.

18 Usually, locust infestation occurs after the period of rains therefore, the immediate drought could hardly have taken place. It also seems strange that the prophet would suggest that the account of the locust attack be retold to subsequent generations if the people face the locust disasters quite often. See Deist, "Parallels and Reinterpretation in the Book of Joel," 64.

19 Ibid.

20 Stuart, Hosea-Jonah, 242.

21 Hosea 4:4 is a difficult text to translate. Andersen and Freedman interpret it thus: "Let nobody else interfere in this quarrel, because my dispute is exclusively with you, O priest!" See Francis I. Andersen and David Noel Freedman, Hosea (AB 24; Garden City: Doubleday, 1980), 345.

22 In a simile, the compared element is not equivalent to that to which it is compared. Barton, Joel and Obadiah, 69. See also Crenshaw, Joel, 122.

23 Crenshaw, Joel, 121.

24 John Strazicich, Joel's Use of Scripture and Scripture's Use of Joel: Appropriation and Resignification in Second Temple Judaism and Early Christianity (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 121; Wolff, Joel and Amos, 44; Sweeney, The Twelve Prophets, 162.

25 See for example, Gary V. Smith, Isaiah 1-39 (NAC 15a; Nashville: B & H Publishing, 2007), 299.

26 For example, it is seen as the coalition of nations under the leadership of the Medes; George Buchanan Gray, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Book of Isaiah, I-XXXIX (New York: C. Scribner's and Sons, 1912), 238.

27 As Strazicich has pointed out, the author of the book of Joel has twofold purpose in creating parallels with Isa 13. First, his intention was to replace the traditional enemy of YHWH (Babylon in Isa 13) with Judah. Thus, he demonstrates that the Lord is at war with his own people. The second purpose is to strengthen the connection with Joel 1:6 and to show that the army and the locust are closely related. See Strazicich, Joel's Use of Scripture, 123.

28 This notion was observed by many scholars. Thus, Marvin Sweeney points out that "the book of Joel equates the threat posed to Israel by nature, employing a locust plague to symbolize that threat (Joel 1:2-20) and by enemy nations (Joel 2:1-14)." See Sweeney, The Twelve Prophets, 151.

29 Katherine Murphey Hayes tries unconvincingly to prove that the lamentation took place. She asserts that Joel 1 portrays natural and human worlds united in the suffering from the consequences of the calamity and assumes that this unity implies a joint participation of nature and humans in the rite of lamentation. However, this is rather an argument from silence and is not convincing. Furthermore, the silence of the prophet may be interpreted in a different way. By mentioning the wailing nature and animals, Joel could be rebuking the people who remain indifferent while even animals heeded his message. See Katherine Murphey Hayes, The Earth Mourns: Prophetic Metaphor and Oral Aesthetic (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2002), 190.

30 For example, "The Lamentation over the Destruction of Ur," translated by S. N. Kramer (ANET, 455-463), "Lamentation over the Destruction of Sumer and Ur," translated by S. N. Kramer (ANET, 611-619), "Lament over Uruk" (SeeM. W. Green, "The Uruk Lament," JAOS 104 [1984]: 253-279).

31 James Nogalski suggests that the end of the book of Hosea is connected to the beginning of the book of Joel through the employment of a similar terminology: "inhabitants" (Hos 14:8; Joel 1:2), "vine" (Hos 14:8; Joel 1:7, 12), "wine" (Hos 14:8; Joel 1:5), and "grain" (Hos 14:8; Joel 1:10). See James D. Nogalski, "Intertextuality in the Twelve," in Forming Prophetic Literature: Essays on Isaiah and the Twelve in Honor of John D.W. Watts (James W. Watts and Paul R. House, eds.; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic, 1996), 113; see also Nogalski, James D. Redactional Processes in the Book of the Twelve (BZAW 105; Berlin: W. de Gruyter, 1993), 13-14. The beginning of the book of Amos and the end of the book of Joel share the same quotation (Joel 4:16=Amos 1:2); see ibid., 42-46. Furthermore, as Nogalski points out, the end of the preceding book appears to be connected to the beginning of the following one thematically or, as he calls it, through the dovetailing genres. Thus, the book of Hosea ends and the book of Joel starts with a call to repentance; the books of Joel and Amos finish and start accordingly with the oracle of judgment against other nations. See James D. Nogalski, "Joel as 'Literary Anchor' for the Book of the Twelve," in Reading and