Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Kronos

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9585versión impresa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.29 no.1 Cape Town 2003

ARTICLES

The domestic context of fine line rock paintings in the Western Cape, South Africa

John Parkington; Anthony Manhire

University of Cape Town

Introduction

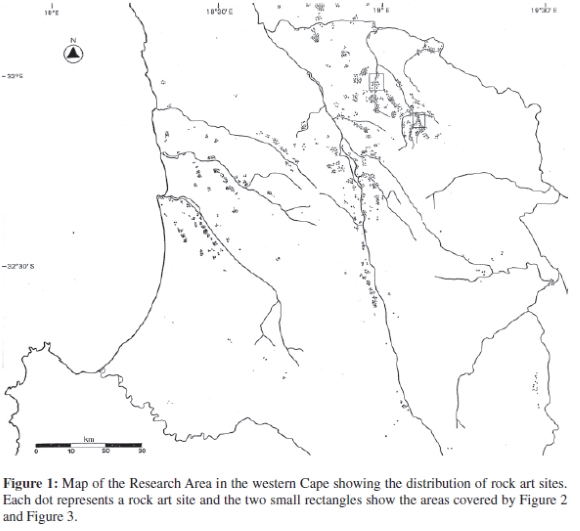

Although rock paintings occur in profusion throughout the landscape of the western Cape, the landscape itself is seldom depicted in the paintings. In this apparent contradiction we see the possibility of describing a relationship between pre-colonial artists and landscape in the western Cape. The observations we present refer to that part of the western Cape between the mouths of the Berg and Olifants Rivers and between the Atlantic coastline and the stone-scrub desert which forms the western margins of the Karoo. This is an area of some ten thousand square kilometres which we have been researching for more than two decades.

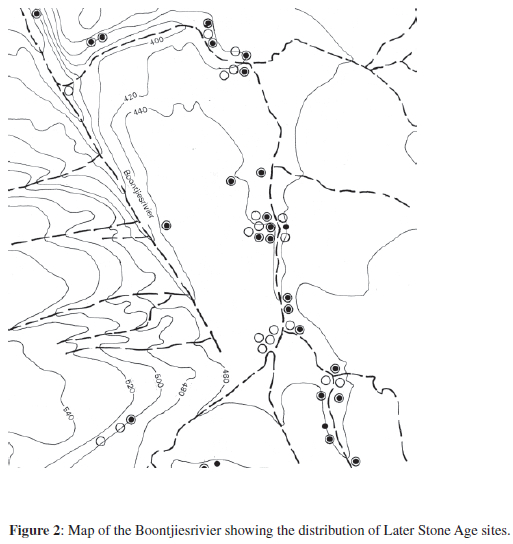

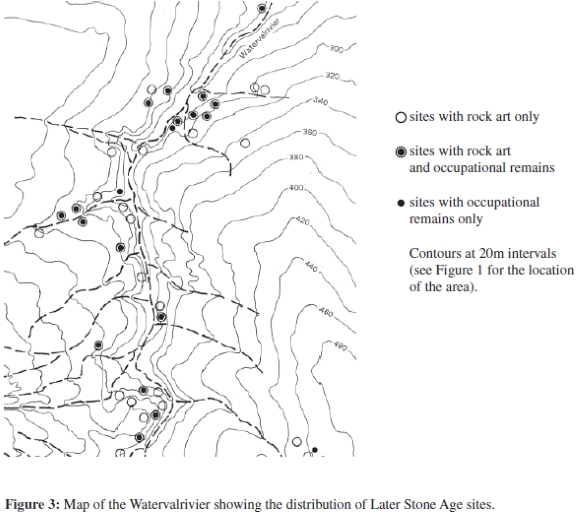

The approach we have always adopted in our surveys is that it is not possible to divorce the rock art from the associated archaeological remains that document the history of hunter-gatherers, herders and even European colonists in the area. To this end we have devoted considerable effort to recording not only the paintings but also the archaeological deposits and artefactual remains that pervade the landscape. These records, combined with the results of excavations conducted in rock shelters, facilitate a basic understanding of the chronology of the area as well as economic approaches and changes of subsistence strategies that occurred through time. The maps shown in Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the kind of reconstructions that are possible from such a data base of information. More than two thousand painted caves or rock shelters and at least fifty thousand recorded images form the basis of our comments. Clearly these images are a residual fraction of what originally existed and must be viewed as a cumulative and deteriorating palimpsest that presented a changing assemblage of references to the viewing population.

The bulk of the representational imagery recorded in our surveys is characterised as having been produced by a fine applicator or brush. This technique allows the creation of thin, well defined lines and outlines and the clear delineation of edges and colour transitions. These are the images which we refer to in this paper as fine line paintings. The colours used include a range of ochreous shades, from yellow through brick red to maroon, as well as black and white. Although many paintings are monochrome, two or more colours are often used in the production of an image. Several images may be juxtaposed in compositions of varying complexity. Paintings which fall outside of the fine line tradition include hand prints, finger dots and finger painting. We believe that the majority, if not all, of the fine line animals and humans painted were the work of hunter-gatherer groups who occupied the area until the appearance of herding some two thousand years ago, and for some time thereafter. We consider the chronology of the art in more detail later in the paper.

As we have noted before,1 painted shelters are very widespread in the western Cape, almost all of them in quartzitic sandstone bedrock, almost none in the few granite areas, although shelters do exist there and were inhabited. Most sites are within sight of several others and many paintings can be seen before the site is entered. Many, but certainly not all, painted images in the western Cape are very small, no more than 300mm in maximum dimension, and often much smaller. Given the fact that much of the critical detail in the images is carried in tiny lines or brush strokes, this means that the paintings have to be viewed from very close to the rock face. We see these patterns as inviting repetitive, perhaps informal, viewing of a semi-continuous set of detailed images across space, without much attempt to discriminate among viewers.

Our experience is, however, that not all parts of the topography are likely to have painted shelters, even though shelters and caves are generally ubiquitous. Paintings are particularly common in low to moderate relief river valley systems and much less so in higher relief land especially away from the streams and rivers. Potentially suitable areas may not have sites if they are particularly high in mountainous terrain, unless they are associated with prominent paths or routes. This overall pattern is still difficult to illustrate because of the incompleteness of our survey and our, perhaps understandable, focus on the lower areas with greater site densities. In our view, there is little evidence to suggest that rock shelters facing in any particular direction were avoided, rather that proximity to pools or running water is one key determinant. Paintings may be in large spherical caves, in smaller rock overhangs or on tiny rock ledges, but most are in situations that offer at least some protection from sun, wind or rain. Although many sites do have spectacular views, it is our impression that overseeing the physical landscape was not the prime requirement for painting at a locality.

The landscape we refer to here is the vegetated topographic surface presented by the physical landform of the western Cape. This landscape is painted in the sense that it is 'littered' with paintings. It is not painted in the sense that within the set of painted images, with a few interesting exceptions to which we return later, we do not find any trace of topography, rivers or vegetation. We now explore these observations, first by redefining landscape as necessarily cultural and then by examining the patterning in the painted record and its locational context. Our objective is to discover the relationship between painters occupying the landscape and a landscape that is seldom represented in the paintings. We are well aware that this contradiction applies to many other painted or engraved landscapes elsewhere in the world, but are increasingly convinced that the relationship in the western Cape between paintings and landscape, in both senses of the word, was quite different from that in many other places, including other parts of South Africa. We also investigate the connection between rock paintings and domestic locations. We use the term domestic site to describe a living place characterised by the presence of a hearth and accumulated occupational remains. This is in contrast to special purpose sites such as factory sites, kill sites and open situation artefact scatters which lack these features.

Physical and Cultural Landscapes

Landscape archaeology is a phrase that has many usages,2 ranging from the study of site distributions on palaeo-land surfaces to the understanding of ancient mindsets.3 What links these together is an interest on the part of archaeologists in discovering how people in the past viewed, characterised and then interacted with the physical landscape in which they lived. The perception of landform, rainfall patterns, vegetation and animal communities transformed the physical landscape into a culturally constructed landscape with meaning and significance. The constructed landscape then became the one lived. Daily activities, beliefs and values all contributed to further reconstructions. The corollary of this is that the archaeological record is a record of that construction and reconstruction, evidence for the differential perception of places on the land.4 In the absence of written documents, relevant ethnography or graphic evidence, archaeologists of the Plio-Pleistocene have been content to map pene-contemporaneous occurrences in the hope of discovering land use patterns. For them the meaning of the word landscape hinges on the recognition of an ancient surface, guaranteeing that artefacts and faunal remains are at least approximately similar in age. It is usually assumed in these cases that any ancient perceptions of landscape are likely to have been strongly ecologically determined.

In the case of the later Holocene populations of the western Cape, we find ourselves in a somewhat intermediate situation, having an abundance of both visual and artefactual material in association with some fragmentary historical and more substantial, but more tangential, ethnographic records from throughout southern Africa. Here we try to link the iconography of the paintings with the locations of painted shelters and other archaeological remains to suggest a possible construction of landscape held by the local population. We accept that the paintings are a manifestation of the construction of landscape and that they were both produced during and subsequently constrained the life experiences of local hunter-gatherers. A recurrent problem is the absence of a good chronological framework for the paintings, subtly pushing us into accepting the pene-contemporaneity of all images and the constancy of landscape perception, something we doubt but cannot easily disprove. Later we return to some of the likely sequencing of paintings and show that this is probably related to a change in the notion of landscape as constructed by successive groups of painters. Key events in this sequence are the appearance of domestic animals and the subsequent domination of certain parts of the terrain by herding people.

Domestic Sites

What is particularly noticeable in the surveys we have done is the fact that living sites are almost always painted and painted sites are almost always either sites where people lived or are very close to them. Figures 2 and 3 below are examples of two locations in the research area of the western Cape that have been thoroughly searched and recorded. The first thing one notices about these maps is that most of the sites are tightly clustered along river and stream courses and that very few sites are found at any great distance from water sources. For the purposes of this paper the sites have been divided into three categories: first, sites which have only rock paintings; second, sites which have rock paintings as well as substantial evidence of occupation; and third, sites which have occupational remains but no rock art. An occupation site is a place where people have lived over a sufficient time for deposit and artefacts to accrue. The deposit contains the accumulated refuse which may include faunal remains, plant food waste and grass bedding material. Artefacts consist of material manufactured or modified by the occupants such as stone tools, shards of pottery and wooden implements.

Taking Figure 2 as an example, out of a total of thirty occupation sites at Boontjiesrivier there are only three which do not have rock paintings. Two of these are stone tool scatters in open locations away from rocky outcrops and thus unsuitable as candidates for rock art. The remaining site is the only rock shelter location which has occupational debris but lacks rock art. In this instance, therefore, rock paintings are almost entirely restricted to domestic locations. A similar situation prevails in the second example at Watervalrivier shown in Figure 3.

A number of points can be made regarding the sites which feature only rock art. Firstly, they are mainly small rock shelters which contain only a small number of paintings. There are no sites in our illustrated sample with a large number of paintings that are not domestic locations. Secondly, although classified as 'rock art only' the majority of these sites do have some artefacts present. This suggests that they were only occupied briefly without the continuous periods of residence needed to establish an archaeological deposit. Thirdly, and perhaps most significantly, almost all these sites are in close proximity to a major domestic focus. These tight clusterings of sites are perhaps best viewed as site complexes with all the sites being inter-connected. One of the most noticeable features of these distribution maps is that rock art sites seldom exist in isolation. There are very few rock paintings away from the main occupation centres and none which are totally separate from the focus of riverine occupation.

As we have noted elsewhere,5 people clearly lived, worked and slept within a few metres of painted images, which must have danced and flickered in the domestic firelight from hearths in caves and rock shelters. Alternatives mentioned in other studies of rock art distributions, that sites may have marked routes, boundaries or lookout points, seem much less satisfactory as descriptions of the locational pattern reported here. Rather, the key word seems to be domestic. Isolation is not a feature of painted sites in the western Cape. Rock art is intimately associated with daily living and exists as a constant backdrop to all the varied domestic activities which occurred in caves and rock shelters.

The Paintings

We believe the iconography of rock art in the western Cape to be critical in understanding the construction of landscape. As in other parts of the world, images here are residual palimpsests from which detail has been lost, in which resolution has diminished. Many animals in the rock art record can be satisfactorily identified to species or at least genus level whilst others are not readily identifiable, often due to poor preservation or lack of image clarity. There is also the possibility that some depictions were never intended to represent actual species. The question of animal identification in the rock art record is always under review with new information becoming available.6 Likewise, many of the human figures can be sexed although others remain indeterminate due to factors such as preservation and poor image definition. This is discussed in more detail below.

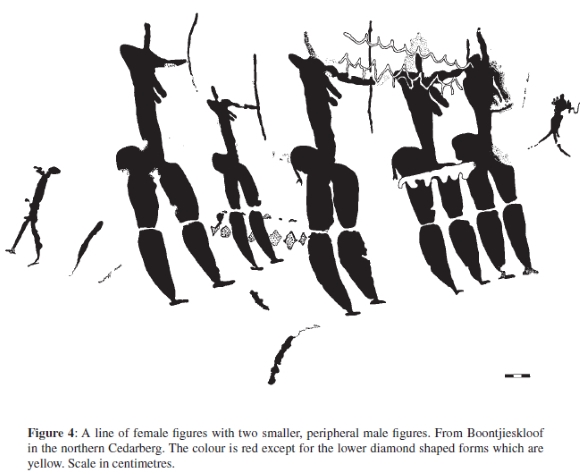

Human figures outnumber animal figures by about two to one, and males outnumber females by about five to one, though this outnumbering varies from sub-region to sub-region, such as between the coastal Sandveld and the interior mountains. There is some separation between male and female figures, achieved either by placing them in different groups or by locating them in particular positions within groups. About half of the human figures recorded, both male and female, are painted as components of lines or processions, many of which appear to be dances.7 In these paintings male and female images are markedly segregated, although there are interesting, and carefully composed, examples with mixed groups. From recent work on human images which do not have surviving recognisable penis or breasts,8 humans can often be sexed using a combination of association, physiological characteristics, equipment and posture. Examples of this are the hunting equipment and bags borne by males and the digging sticks and collecting bags carried by women. Similarly, slender bodies and slim legs with well-shaped calves are normally male prerogatives whilst steatopygous figures are normally female. By incorporating these features we can increase the numbers of sexed individuals and add to our understanding of the occasions and events depicted. The state of preservation of human figures plays a significant role in our ability to recognise gender. The clarity of images ranges from exceptionally good through to very faint examples that are barely recognisable as human. Virtually all the well preserved images can be sexed whilst a large proportion of the faint images remain impossible to verify. Some of the images which seem lack any obvious gendered features are the so-called 'stick figures' which are almost caricatures of the human form.

The arrangement of some of the lines of women, with men either absent or depicted as token males in a predominantly female event , are likely representations of first menstruation dances, as in Kalahari Eland Bull dances. Figure 4 depicts a line of five right-facing women carrying sticks with two much smaller male figures placed at either end of the female line. In some other paintings groups of seated women are depicted clapping as if accompanying some dance, possibly a healing dance. If we follow analogs from the Kalahari, we would recognise that these occasions are domestic events located in a campsite. Support for the idea that these processions are dances, comes from a strong pattern of directionality. Almost all, but not quite all, of the lines of men and women face right. Our counts make it clear that there is a strong preference for figures, which are almost always painted in side view, to face, that is 'appear to move', right. Movement is the key concept, because movement is not possible without both time and space. The painter wishing to impart the notion of movement, as in a dance, would have been constrained to use direction as a device. In this way time and movement are spatialised,9 with the decision being that right signifies 'after' or 'later', left 'before' or 'earlier'. This conventional pattern re-appears in paintings of animals as we explain later. Although other episodes involving movement may be, and probably are, depicted, the repeated postures and repetitive paraphernalia of processions seem more consistent with dancing occasions. From ethnographic comparisons we may detect girls first menstruation, boys first kill and healing dances marked by details depicting altered states of consciousness.

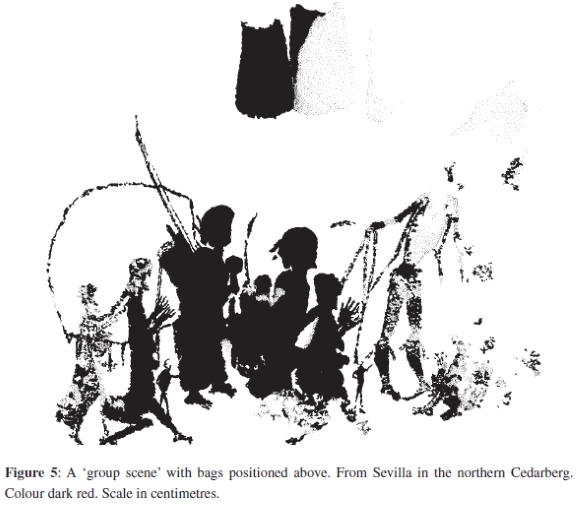

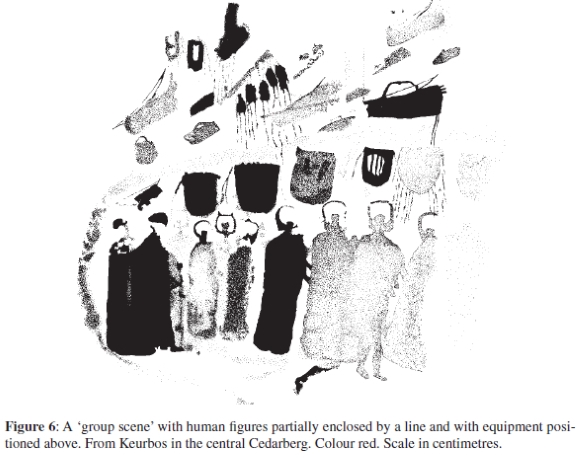

An important exception to this pattern of linear compositions is the 'group scene' described in a number of previous papers,10 and which often include both male and female human images. A key feature of these compositions is the set of hanging bags (Figures 5 and 6), which are placed above the seated humans and apparently meant to be read as hanging from pegs driven into the walls of rock shelters. We have found many such wooden pegs still in place in shelters of the western Cape. Typically, these are found in caves and large shelters with occupational deposit where the pegs have been pushed into horizontal cracks in the back wall. They are usually pointed at one end and many appear to have been fashioned from digging sticks, presumably broken or discarded items, which have found a useful secondary function as pegs. They are normally placed at a suitable height above the deposit where they could act as convenient hooks for equipment such as bags. A good example of this practice is found at the large overhang at Perdekraalkloof (close to the Boontjiesrivier shown in Figure 2) where four wooden pegs were found placed in a line in the same crack near the centre of the rear wall. Two illustrations of group scenes are provided. Figure 5, although not well preserved, still clearly depicts human figures beneath a set of hanging bags. The standing figure positioned towards the right hand side of the composition has a penis and is clearly male. Two other figures with bows are also presumed to be males. The kneeling or seated clapping figures are probably female. Figure 6 depicts a number of human figures partially enclosed by a thick red line. Several items of equipment are shown suspended above the figures including bows, hunting bags and women's collecting bags.

Among possible references implied by these patterned compositions, one prominent one is surely that of the domestic location. These paintings are often placed carefully in small recesses that mimic the cavity of a rock shelter and betray an interest in depicting the group 'at home'. On occasion the bags hang from a curved painted line, which we take to represent the confines of a cave or rock shelter. This reference to cave or rock shelter is, as we hinted earlier, one of the few attempts in the painted record of the western Cape to depict a component of the physical land form. There are no persuasive rivers, hills, trees or other vegetation.

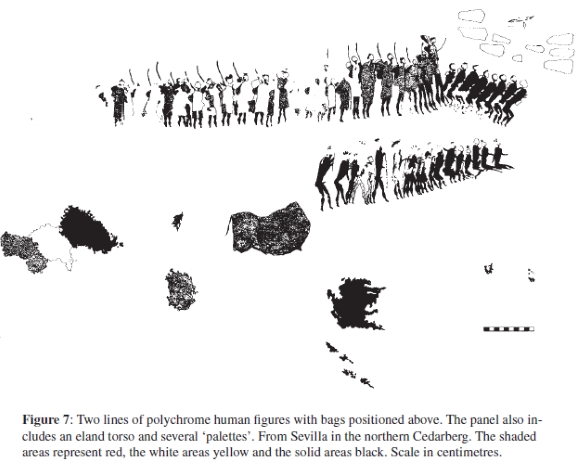

The devices of painted hanging bags and curved rock walls are reused in two other contexts. One is a processional scene which, elsewhere,11 we have interpreted as an initiation event for young men (Figure 7). No women are painted in this composition and the hanging bags, on this occasion hunting bags from their shape, are set at the destination of the direction implied in the procession. We have argued that these bags are a symbol of the adult hunter status after the killing of a first eland. The 'cloaked' humans, depicted in the top row of human figures, are assumed to represent initiated men. Reference to ethnographic photographs and drawings show that the painted cloaks are not literal images of garments but rather a device to reveal to the viewer the status of the individuals depicted.

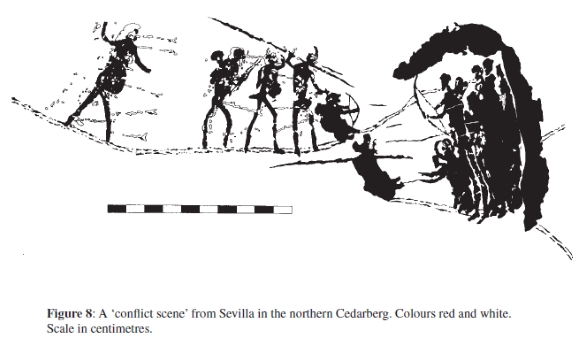

The other context is, at least at one level, a conflict scene, also much illustrated in previous work (Figure 8). Here the conflict is between two groups, one of which is painted within a convincing representation of a cave or rock shelter. Furthermore, the artist has enhanced the conception of a cave by placing the thick curving red line around a natural indentation in the rock. This has implications for the composition as a whole as the use of natural feature in the rock determines the way the rest of the images are placed on the rock surface.

Although it is obviously difficult to try to summarise the contexts of painted human images in such a diverse assemblage, we would argue that the overwhelming subject choice of these images is one of domestic events and personal life histories. By this we mean that ceremonies marking first kills and first menstruations, healing dances and some conflicts in compositions reflecting domestic camps, foreground the domestic and the personal ahead of the public or the cosmological. We have argued elsewhere that the choices of images refer to the domestic politics of men and women as they pass through their distinct but related life histories.12These are domestic in the sense that they are played out in innumerable personal contexts by individual men and women and at various social occasions. It is surely also significant that the only attempt to use or depict a topographic surface is where a cave or shelter is painted into a composition or implied by the positioning of a composition. And the caves are where people live.

Animals are an important, if less numerically dominant, element in the painted imagery of the western Cape. Whereas humans are occasionally, as in the case of the painted caves, located with some reference to their physical surroundings, it is much rarer for an animal image to be contextualised by any indication of surface, topography or association. One case in point is the issue of small bovids and nets which is dealt with later. Despite the presumed detailed understanding of the ecology, behaviour and demography of animals of all sizes, it is remarkable that no interactions between animal and animal, animal and plant or animal and physical surroundings are attempted in the paintings. Animals are painted in frequencies that do not reflect natural abundance but presumably approximately proportional to the symbolic and referential significance of different forms. In terms of the construction of landscape by the artists, painted animals demonstrate a disinterest in the physical context and a subordination of the environmental to the social.

Eland paintings are very common in the western Cape, as elsewhere in southern Africa. We have suggested that this emphasis reflects the sustained use of the eland, or other large game equivalent such as the gemsbok, as a key metaphor in organising relations between men and women.13 As others have noted, relations between a man and his wife are often expressed, typically indirectly, in terms of carnivore and herbivore, as a parallel to the relationship between the man as a hunter and the eland as his prey.14 If this is substantially correct, it implies that a large proportion, though not all, of the animal paintings make reference to human relations in the lives of hunters and gatherers. These metaphors apply specifically to the adult phases of men's and women's lives, which they enter at the initiation ceremonies that we also find painted, as described earlier.

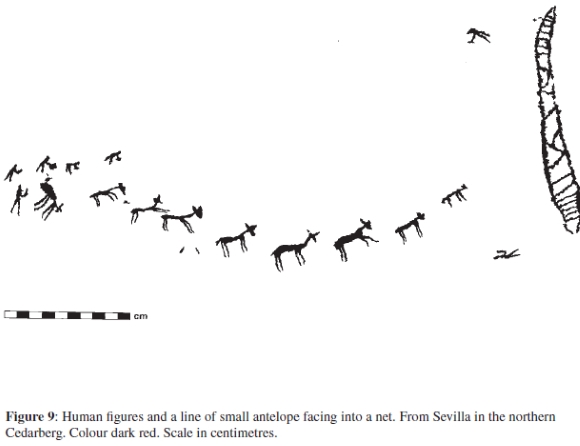

Of particular interest are those activities involving both humans and animals which are very rarely depicted in compositions. There are, for example, very few paintings of hunting episodes. The majority of depictions of bows in use are compositions involving human figures arranged so as to imply conflict between groups of men. Compositions that show men hunting eland with bows are extremely rare, though men, eland and bows are all very common. There are a number of paintings depicting the hunting of small bovids with nets, which do throw interesting light on the painting of landscape (Figure 9). These compositions include some human figures, often depicted funneling the animals, one or more nets, either with the upright support sticks or stick handles shown, and one or more small bovids 'moving toward' the net(s). Despite the fact that these activities must have had very specific locations in order to function effectively, no attempt is made to illustrate the context. As with the wooden pegs in the 'group scenes', the paintings end at the upright sticks and wooden handles, seemingly the interface here between the social, or technological, and the topographical. Whatever the purpose of the net paintings they needed no environmental or topographic context. They do add support to the interpretation of directionality offered earlier, because all but two of the twenty-four net scenes we know of have the net to the right. Once again movement, this time of the small antelope toward the net, is from left to right.

From these locational and iconographic patterns we can suggest that the paintings are in the domestic contexts and the domestic contexts are in the paintings. The interface between the painter and the physical landscape is through the rock face, almost always a surface at or close to the place where people camped, lived, worked and slept. In addition, the painting distribution follows the dispersed pattern of domestic imprinting on the land, scattering a series of images linked by form, content and meaning across space, following the stream courses. It is hard not to see this pattern as a painted version of domestic life lived in a marvelously dramatic landscape.

Landscape as Experience

There would seem to be a temporality as well as a spatiality about the notion of landscape, with the implication that the construction derives from many lives lived and many tales told. What then are the memories and experiences that have been painted onto cave and rock shelter walls in the western Cape as part of the transformation of land into landscape? We have argued here that there is little in the painted imagery to directly support the idea that relations between people and supernatural forces or ancestral beings are central to their meaning. There are, however, repeated compositions that refer to the events of peoples' lives, the occasions that define personal identities and the moments of significance in interpersonal relations. Processional paintings recall the dances that mark ceremonies of transition. These paintings are further embedded in the domestic context by placing them within accessible places close to the chosen locations of domestic life. Unlike areas such as the Drakensberg, clearly recognisable conflations of animal and human forms are very rare in the western Cape. As Jolly notes, there is considerable variation in the way human and animal features are combined to the extent that they almost defy classification. This is certainly true of the western Cape where each example is virtually unique. The only exception are the elephant-headed men which, although present at only three sites, do conform to a recognisable pattern. In all senses of the word, therianthropes demonstrate ambiguity.15 This may reflect the interpenetration of the real and hallucinatory world16 as well as the permanent ambiguity in relation to the nature-culture boundary ascribed to southern African hunter-gatherers.

The recorded cosmology of southern San hunter-gatherers, best documented for twentieth century Kalahari and nineteenth century Karoo contexts, seems to reflect few direct relationships with specific topographic features. Rather, we could argue that, like the paintings, the stories are used to create a set of domestic relationships and describe a set of required interpersonal behaviours. The stories provide the justification for proper conduct and embed such conduct in ancestral events and life histories acted out by ancestral families. Landscape features are only occasionally and never centrally involved.

In similar vein, there is little direct support in the ethnography or ethno-historic texts from southern Africa for the idea of the rock face as an interface between two worlds. There is, however, a great deal of reference to the spirit world.17In spite of the fact that in the western Cape the majority of rock shelters with paintings were places to live, work and sleep rather than places to enter another world there was an obvious inter-connectivity between the domestic and cosmological domains. There are very few paintings in the western Cape that can plausibly be said to enter or emerge from the rock face. However, there are some images which face into cracks or depressions in the rock face as well as images with extensions leading towards natural declivities in the rock surface. Modifications of existing images certainly exist in the form of repainting and the apparently deliberate smearing of some paintings of humans and animals.18 One of the most interesting features in the western Cape painted repertoire are the so-called 'palettes'. These are small areas of paint, non-representational in form, some of which have been deliberately rubbed smooth. Examples of 'palettes' can be seen in Figure 7. The most economical explanation for these 'palettes' is that they were reservoirs from which supernatural power could be drawn.19 These examples suggest the even in domestic locations there was no absolute separation between the personal and the cosmological realms.

We conclude that the construction of landscape by recent and more ancient hunter-gatherers of the western Cape was based on lived experience rather than on mythic moments. Landscapes are described in terms of events that everyone can claim to have experienced, except perhaps the memorable or exceptional cases. Learning the landscape meant accessing a constantly changing framework that had largely functional significance, not gaining secluded or restricted instruction about an unchanging set of mythically rooted, not to say routed, stories and names. A named locality might be the place where a hunter killed three wildebeest in an afternoon or the pan with the crooked thorn tree, but later might be renamed after a subsequent memorable event or feature. This reading is consistent at least with the corpus of remnant stories, the detailed ethnographies and the content and placement of painted imagery across the physical terrain. It also explains the absence of topography in the paintings, because there was no need to refer to events that connected ancestral beings with remarkable land forms.

Although the rock paintings, as viewed today, tend to promote an illusion of contemporaneity the production of art has a long history in the western Cape. Similarly, image production was not a static process but underwent a number of changes, some of which we are able to detect and link to the basic chronology of the area as revealed from archaeological excavations. Most of the existing rock art was probably done between about 7000 years ago and about 300 years ago, when European colonists began spreading through the western Cape . A period of fairly intensive occupation began around 4000 years ago as attested to by the number of archaeological deposits which date to the period 4000 to 2000 years ago. We believe that most of the fine line imagery is older than 2000 years and thus predates the advent of pastoralism in the western Cape. Although the precise mechanism by which pastoralism was introduced is not well understood, it is likely that the earliest livestock and pottery reached the Cape around 2000 years ago by a process of diffusion. The actual migration of Khoi herders may not occurred until the end of the first millennium AD.20

The appearance of pastoralism is fairly well documented with pottery and sheep bones first appearing in deposits near the coast about 1600 years ago and slightly later in the interior mountains. These events are also recorded in the rock art in the paintings of fat-tailed sheep although they are only present in small numbers. The sheep paintings are stylistically rooted in the fine line tradition and their brief appearance would seem to coincide with the decline of that tradition. Significantly, there are no paintings of cattle in the western Cape although cattle were present in large numbers when European colonists arrived in the Cape. It would seem that the fine line tradition endured long enough for sheep to be included in the painting record but disappeared before cattle arrived in the Cape.

During the relatively short period between the introduction of pastoralism (about 1600 years ago) and contact with European colonists (about 300 years ago) there were significant changes in the production of the rock art. The most obvious modification is the shift away from fine line representations to the technique of painting with hands and fingers. The most dominant manifestation of this trend is the widespread making of hand prints. Hand prints differ from fine line images in that they are often concentrated in a few sites where, characteristically, they form clusters or lines of very similar but not quite identical images. Measurements show that the majority of prints were the work of teenagers, implying that they were part of a tradition of initiation,21 but one that used different images and perhaps different occasions to celebrate these events.

The contrast between the fine line painting tradition and the handprint tradition seems best interpreted as a change in the relationship between people and the occasions of image making and placements of images as landscape marks. We believe it was a marked discontinuity in the circumstances and significance of applying paint to cave walls. Whereas the fine line emphasis seems to have been on intra-social relations, the almost exclusive focus on hand printing that we propose for the final millennium of pre-colonial history, may have helped to define who is 'us' and who is not. As landscape marking this is dramatically different from what has gone before, when the emphasis seems to have been on relations 'among us'.

1 J.E. Parkington, 'Interpreting paintings without a commentary: meaning and motive, content and composition in the rock art of the western Cape, South Africa', Antiquity, vol. 63, 1989, 13-26; J. Parkington and A. Manhire, 'Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the Western Cape, South Africa' in M.W. Conkey, O. Soffer; D. Stratmann and N.G. Jablonski, eds., Beyond Art: Pleistocene Image and Symbol (San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences, 1997), 301-20.

2 W.A. Ashmore and A.B. Knapp, eds., Archaeologies of Landscape: Contemporary Perspectives (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999).

3 See for example T. Ingold, The appropriation of nature: essays on human ecology and social relations (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986); R.J. Blumenschine and F.T. Masao, 'Living sites at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania? Preliminary landscape archaeology results in the basal Bed II lake margin zone,' Journal of Human Evolution, vol. 21, 1991, 451-62; M.J. Hall, 'High and Low in the townscapes of Dutch South America and South Africa: the dialectics of material culture,' Social Dynamics, vol. 17(2), 1991, 41-75; B. Bender, ed., Landscape: Politics and Perspectives (Oxford: Berg, 1993); R. Bradley, Rock art and the prehistory of Atlantic Europe: signing the land (London: Routledge, 1997); J.E. Parkington, 'Western Cape landscapes' in J. Coles, R. Bewley and P. Mellars, eds., World Prehistory: Studies in Memory of Grahame Clark (Proceedings of the British Academy 99, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999); K.F. Anschuetz, R.H. Wilshusen and C.L. Scheick, 'An archaeology of landscapes: perspectives and directions', Journal of Archaeological Research, vol. 9(2), 2001, 157-211.

4 Ingold, The appropriation of nature: essays on human ecology and social relations; Blumenschine and Masao, 'Living sites at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania? Preliminary landscape archaeology results in the basal Bed II lake margin zone'; Hall, 'High and Low in the townscapes of Dutch South America and South Africa: the dialectics of material culture'; Bender, ed., Landscape: Politics and Perspectives; Bradley, Rock art and the prehistory of Atlantic Europe: signing the land; Parkington, 'Western Cape landscapes'.

5 Parkington, 'Interpreting paintings without a commentary: meaning and motive, content and composition in the rock art of the western Cape, South Africa'; Parkington and Manhire, 'Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the Western Cape, South Africa'.

6 E.B. Eastwood, C. Bristow and J.A. van Schalkwyk, 'Animal behaviour and interpretation in San rock art: a study in the Makgabeng plateau and Limpopo-Shashi confluence area, southern Africa,' Southern African Field Archaeology, vol 8, 1999, 60-75.

7 Parkington and Manhire, 'Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the Western Cape, South Africa'.

8 K. Smuts, 'Painting people: an analysis of depictions of human figures in a sample of procession and group scenes from the rock art of the southwestern Cape' (Unpublished Honours dissertation, Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town).

9 A. Solomon, 'Division of the Earth: Gender, Symbolism and the Archaeology of the Southern San' (Unpublished Masters dissertation, Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town, 1989).

10 T.M.O'C. Maggs, 'Microdistribution of typologically linked rock paintings from the western Cape' in J.J. Hugot, ed., Procedure du sixième congres panafricain de préhistoire (Dakar, 1967, 218-220); A.H. Manhire, J. Parkington and W.J. van Rijssen, 'A distributional approach to the interpretation of rock art in the southwestern Cape,' South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series, vol. 4, 1983, 29-33; Parkington, 'Interpreting paintings without a commentary: meaning and motive, content and composition in the rock art of the western Cape, South Africa'; Parkington and Manhire, 'Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the Western Cape, South Africa'.

11 Parkington and Manhire, 'Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the Western Cape, South Africa'.

12 J.E. Parkington, 'What is an Eland: n!ao and the politics of age and sex in the paintings of the western Cape' in P. Skotnes, ed., Miscast: negotiating the presence of the Bushmen (Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, 1996); J.E. Parkington, 'Men, Women and Eland: Hunting and Gender among the San of Southern Africa' in S.M. Nelson and M. Rosen-Ayalon, eds., In Pursuit of Gender (Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 2002).

13 Parkington, 'What is an Eland: n!ao and the politics of age and sex in the paintings of the western Cape'; Parkington, 'Men, Women and Eland: Hunting and Gender among the San of Southern Africa'; Parkington and Manhire, 'Processions and groups: human figures, ritual occasions and social categories in the rock paintings of the Western Cape, South Africa'.

14 J.D. Lewis-Williams, Believing and Seeing: Symbolic Meanings in Southern San Rock Paintings (London: Academic Press, 1981); R. Hewitt, Structure, Meaning and Ritual in the Narratives of the Southern San (Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 2, Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag, 1986); D.F. McCall, 'Wolf Courts Girl: the equivalence of Hunting and Mating in Bushman thought', Ohio University Papers in International Studies, Africa Series, vol. 7, 1970; M. Biesele, Women Like Meat (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993); A. Solomon, '"Mythic Women": a study in variability in San Rock Art and Narrative' in T.A. Dowson and J.D. Lewis-Williams, eds., Contested Images (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1994), 331-71.

15 P. Jolly, 'Therianthropes in San rock art,' South African Archaeological Bulletin, vol. 57, 2002, 85-103.

16 J.D. Lewis-Williams and J.H.N. Loubser, 'Deceptive appearances: a critique of southern African rock art studies' in F. Wendorf and A.E. Close, eds., Advances in World Archaeology (New York: Academic Press, 1986), 253-289.

17 J.D. Lewis-Williams and T.A. Dowson, 'Through the veil: San rock paintings and the rock face', South African Archaeological Bulletin, vol. 45, 1990, 5-16.

18 R. Yates and A. Manhire, 'Shaminism and Rock Paintings: Aspects of the use of Rock Art in the South-Western Cape, South Africa', South African Archaeological Bulletin, vol. 46, 1991, 3-11.

19 Ibid.

20 K. Sadr, 'The first herders at the Cape of Good Hope', African Archaeological Review, vol. 15(2), 1998, 101-132; A.B. Smith, 'Early domestic stock in southern Africa: a commentary', African Archaeological Review, vol. 15(2), 1998, 151-156.

21 A.H. Manhire, 'The role of handprints in the rock art of the south-western Cape', South African Archaeological Bulletin, vol. 53, 1998, 98-108.