Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Kronos

versión On-line ISSN 2309-9585versión impresa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.27 no.1 Cape Town 2001

'Shoot to Kill': photographic images in the Namibian Liberation/Bush War

Casper W. Erichsen

University of Namibia

Introduction

The Namibian Independence War has been described as "so clandestine that it will take the 30 year rule to unlock its secrets".1 The difficulties of coming to terms with such a war arise in part from its sheer brutality; nor has post-independent Namibian society submitted itself to an introspective therapy in relation to the 'national' trauma (such as South Africa has attempted with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission) and, as such, diffuse memories and vivid mental scars persist.

The focus here will be on the last six years of this struggle, namely 1984-89. These six years represent a part of this 'national trauma' that is still fresh in people's minds.2 On-going debates about the war occur in the shape of, for example, ex-combatant protests, films,3 letters from 'concerned citizens' in the print media, and more informal public debates which might take place at cafes and bistros. These testify that views about the war are many and diverse. The different labels given to the armed strife at the time serve as indications of the varied understandings of both purpose and nature of the war. The South African media continuously referred to the Bush or Border War; a label that was vaguely descriptive in terms of certain geographical and colonial realities of the war, but at the same time also conveniently neutral in its relation to any philosophical or political reasoning behind the very costly fighting. In contrast, SWAPO and the numerous solidarity movements abroad related a different, more direct, sense of purpose in describing the war as the Namibian liberation struggle.

This article looks at the role of the media - and specifically its photography - in the creation of different ways in which Namibia's liberation/Bush War was experienced and perceived, and is remembered. It will further be investigated to what extent images were deliberately arranged and created to mould such perceptions in a vigorous propaganda war. It could be argued that the divisions, in terms of interpretations and understanding of the war that linger in contemporary Namibia, partly stem from the propaganda war congruent to the physical fighting.

The approach here is a comparative analysis of four sources depicting three largely different interpretations of the war, as represented in The Namibian, The Combatant, PERGAMUS and PARATUS. Photographs purporting to represent specific realities will be 'read' and analysed from the selected sources, in relation to their accompanying texts. Discussion centers on recurring themes found in the images, always bearing in mind John Berger's point that "the way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe",4 and that the author's reading here may differ from those of the intended audiences.

Obviously, given the subject matter, the reproduction of images in this article is at times of an explicit nature. The politics of reproducing images of war and brutality are highly contentious, with Sontag for example arguing that publication of condescending, intrusive, humiliating and morbid pictures for the sake of making a point is to sublimate an already committed 'murder'. However, one of the points made in this article is that given the often atrocious nature of war, the images and depictions of the liberation/Border War were surprisingly mild. Another, related, aspect is whether censoring such images would in fact contribute to the ongoing silence surrounding the war. The issue of 'reconciliation' is complex and will not be elaborated upon here, though it is worth noting that the Namibian government issued a vaguely formulated notion of forgiving but not forgetting. No attempt at public dialogue has accompanied this 'position'. Such a government ratified, if not dictated, stance on national reconciliation of course leaves many Namibians in a dilemma. On the one hand, the 'silence' has proved relatively successful in as much as the potentially explosive racial tension before independence has been contained. Yet the silence sits uncomfortably with amongst other things the growing sense of what the past means in Namibia, and how history bears on the present. It is from the relatively privileged space of the academy that I argue that photographic images, as 'documents' on the war, should not be censored now (as they were previously) and that certain explicit images have been included in this article. Unfortunately, the authorship of most photographs are rarely accredited, so rather than referencing the author/photographer, reference will be given to the journal or paper in which they appeared.5

Visual Analysis

The photographic medium is rarely used as a source in its own right when it comes to historical analysis and interpretation. The medium has typically been overshadowed by the written word, or at best stood as silent, 'illustrative' evidence to support a textual line of argumentation:

Most researchers of Africa's social history have had limited interaction with photographs... In general, visuality is subordinated to textuality which itself is grounded and empirically validated by reference to documents and sources from the privileged site of the archive.6

Except for The Colonising Camera edited by Hartmann, Hayes and Silvester, there exists very little analytical work relating to photography in Namibia, even less that deals with the liberation/Bush War. Although The Colonising Camera deals with a period and context that are remote from the images of the last years of the war for Independence, it does, however, offer a very useful precedent, particularly Landau's article which deals with the physical and semantic violence inherent in photography.7

Before Independence several 'coffee table'-type books were published, depicting the military prowess of the South African Defence Force (SADF) and its offspring the South West African Territorial Force (SWATF). Stefan Sonderling's Bush War (1980), Hooper's book Koevoet! (1988), and Steenkamp's photographic ode South Africa's Border War 1966-1989 (1989), are but a few examples of images and rhetoric from the counter-insurgency side.8

Ten years after Namibia's independence, several publications have emerged which attempt to seriously anaylse the liberation/Bush War. None of these publications apply any sort of analysis to the photographic images they use, although Heywood does address the related issue of representation and propaganda.9

The four sources used in this article were quite different in their reporting and reflections on the same subject matter, the war. Whereas PARATUS, PERGAMUS and The Combatant all had direct military purpose - in as much as they were published largely for a military readership - The Namibian rather had a much broader target group. Although not all would have admitted to it at the time, The Namibian was widely read - across the apartheid divide. Gwen Lister, as editor and founder of the newspaper, remembers the initial underground success of The Namibian: "The couple of whites who would buy the paper, would go into a store and then would turn the paper inside out and walk out of the shop [so] that it couldn't be seen." 10

In the 1980s The Namibian dared to 'show' what few others inside the country did. Their candid news coverage more often than not put them at odds with the South African military presence in Namibia. Gwen Lister elaborates: "...they [the military] had a very compliant media in Namibia until The Namibian started up, and started graphically showing the images of what they actually did." 11

Although The Namibian was viewed by many to be affiliated with SWAPO, and to some extent there must have been certain shared sympathies,12the paper was not directly related to the liberation movement SWAPO. The Combatant, however, was a SWAPO publication. The monthly journal was published outside of Namibia and concerned information for and about the People's Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN), which was the military wing of SWAPO. The journal contained descriptions of PLAN activities, letters from readers, and high level analysis of historical and contemporary events. The textual and visual rhetoric clearly reflected the anti-colonial nature of SWAPO in its highly polarised descriptions of the war.

PARATUS and PERGAMUS were South African funded military 'magazines'. The former was published by the SADF and sold through the Central News Agency (CNA), which was a distributor of the South African government at the time. Gavin Ford who wrote and took pictures for the journal in the mid-1980s, stationed in Windhoek, describes the journal as follows:

The style of PARATUS was pretty pedestrian ... its main purpose was to serve as a subscription magazine to permanent force members ... In the late seventies and early eighties, comments from 'liberal' students snidely, yet accurately, tagged the magazine: PARRO-TUS ... The official magazine of the South African Offence Farce.13

The 'sister' magazine PERGAMUS, which was published for SWATF conscripts, was in many ways a cheaper edition of PARATUS. PERGAMUS contained fewer colour photos, in fact less images altogether, and could not boast the glossy appearance of PARATUS. The most significant distinction between the 'magazines' was that the SWATF publication dealt with all-Namibian issues, be they military history, politics, or news.

All four publications served their own special purpose in the period of study, and their rhetorics (in image and text) should be viewed/read within the relevant historical context. The four publications projected at least three different approaches to the central subject matter of the Namibian liberation/Bush War.

War Escalation

In 1978 the Security Council of the United Nations (UN) passed a new resolution concerning the status of Namibia. Resolution 435 stated that the UN would remain committed to the implementation of Namibian independence. Only nine days prior to the passing of Resolution 435, Pieter Willem Botha became Prime Minister of the Republic of South Africa, plotting a new and more aggressive course for the country, and seeking against the odds to preserve white minority rule. In addition, US diplomacy through the 1980s linked the presence of Cuban troops in Angola to the illegal presence of South African troops in Namibia: as long as the Cuban troops were lodged in Angola, South Africa was able to justify its military presence in Namibia.

In this context, the struggle for Namibia's independence intensified. The escalation of war was particularly felt on the South African economy. In 1985, The Cape Times reported that "over 100 000 South African-controlled troops have been stationed in the country" and that "Pretoria has spent more than R3 million a day [fighting in Namibia]".14 The economic strain, however, was not the only implication for the South African Republic. The amount of "combat-related deaths", up till that point, was officially estimated by the South African Defence Force as being 715 people (comprising SADF, SWATF, SAP & SWAPOL figures). The potential public outcry following this news was appeased by contrasting it with the 11 291 PLAN soldiers whom South Africa claimed to have killed.15

The implications of war are always severe, yet the South African government was not eager to publicise the actual effects of the conflict on its usually rather young conscripts. Although the figures cited in The Cape Times clearly demonstrated a South African superiority in terms of a bare body count, the statistic did not take into account the physical and psychological effects felt by those implicated by the actual fighting. The traumatic experiences of the battlefield undeniably impinged on the civilian and military population alike. The emotional scars ran (and still run) deep in the generation of South Africans and Namibians who were forced into the bloody border war, as either active or passive participants.

From 6 September 1980, National Service was made obligatory for all Namibian males between the ages of 18 and 55. For once the apartheid system was colour-blind. In order to uphold the questionable virtues of the apartheid system, black, coloured, and white Namibians were drafted into the South West African Territorial Force (SWATF). Forced conscription was an effective catalyst for increased divisions in a society that had already been fragmented by apartheid legislation. All families now had to decide whether their sons and fathers were to fight for the SWATF, with the implications that it bore, or whether they were to risk their lives going into exile. Eventually as many Namibians fought for SWATF as for PLAN - leaving a painful legacy of split loyalties for many families.

SWATF was just one of the options for the Namibian conscript; another was Koevoet. This particularly nasty SAP/SWAPOL Counter Insurgency Unit, attracted massive attention for its brutality.16 The Koevoet unit was commanded by the white Brigadier Hans Dreyer, but consisted largely of black Namibians conscripted through the police force. These were often criticised for being poor and uneducated. In Nine Days of War Peter Stiff related a typical apartheid reasoning for recruiting black Namibians into Koevoet: "Because of the circumstances of war...the principle and most important qualifications for black policemen serving in the unit [Koevoet] were tracking and fighting abilities. The lesser educated, more primitive and closer to nature, were usually better trackers." 17 Herbstein and Evenson have pointed out that "poverty and unemployment were powerful recruiting Sergeants" in the case of unemployed and uneducated Namibians.18

The mid- to late-1980s were marked by countless small-scale clashes between PLAN and SWATF/SADF. The importance of the 'body count', as seen in the Vietnam War, was not lost in the desperate defence of apartheid. The war was becoming increasingly prone to boastful military prowess and exclamations of the virtues of a 'just' cause. The result of one such 'operation', according to the South African military journal PARATUS, was 57 dead PLAN fighters in 36 contacts approximately forty kilometres inside Angola.19 No mention was made of any South African casualties. The same phenomenon was to be observed in the SWAPO publications where few casualties were had and many begot.

PLAN retaliation often came in the shape of sabotage and attacks on military bases in Namibia. Some attacks were boasted and other incidents not. With the South African (especially Koevoet) practice of and growing reputation for playing 'dirty tricks' it was an arduous job to tell truth from lie. On the 19th February 1988, a bomb blew up the First National Bank in Oshakati, killing a large number of civilians. The aftermath was typical of the time as both sides blamed the other for the incident, in an intensifying flurry of propaganda and counter-propaganda, denial and accusation.

The end of the lies seemed near when the unofficial armistice between the warring parties was begun on 1st September 1988. But, on the first official day of the UNTAG-supervised ceasefire, April 1st 1989, fighting once again broke out. Koevoet soldiers engaged returning PLAN fighters on the border with brutal force, causing substantial SWAPO losses. The Koevoet units claimed that the PLAN fighters had attempted an armed invasion of Namibia. The accusation was firmly refuted by SWAPO. Rather, SWAPO claimed, the soldiers had attempted to surrender their weapons to the UNTAG troops, who were supposed to have been in place on the border. The incident almost ended the transition to independence before the process had really begun.20 Fortunately, the transition was brought back on track and after the first general elections in late 1989, Namibia celebrated its new status as an independent nation under the leadership of the liberation movement SWAPO, on 21 March 1990.

Mise en Scène

In 1867 William Coates Palgrave arrived in Namibia with the photographer F. Hodgson. Together they compiled an impressive amount of photographs, depicting local leaders and landscapes. Their work had been commissioned by the Cape Parliament which had expressed an interest in the territory. Hodgson and Palgrave's portraits of Herero Paramount Chief Maharero (see Figure 1), Kaptein Jan Jonker Afrikaner and other 19th century Namibians described their subjects with a measure of respect; photographic plates, as used by Hodgson, were far less sensitive to light than modern film roles, and the subsequent dependency on long exposures resulted in inherently posed compositions. A hint of the photographic agenda is given in The Colonising Camera: "The [Palgrave] album offered politicians and interested persons in the Cape and London a series of images showing potentially co-operative indigenous leaders, posed with self-contained dignity and intriguing landscapes criss-crossed by roads and wagon trails." 21

If indeed this photographic expedition was the colonial probe that The Colonising Camera suggests, it is not unlikely that the first significant use of photography in Namibia served as a weapon in the opening battle for territory on the subcontinent. The employment of photography by Hodgson and Palgrave, in the meticulous choreography of their portraits, demonstrated the allegiance of the photographic medium to its employee. At this time, and indeed ever since, photography was and is being put to constant new use around the world. The emerging new social sciences soon canonised the medium as reliable scientific evidence, in accordance with the notion that 'seeing is believing'. One of the characteristics of photography is "the fact that it appears to have a special relationship to reality. We speak of taking photographs rather than making them." 22

Indeed, photographs have a remarkable force in that we are quick to accept them as undiluted, uncorrupted reflections of reality. The real power of photographs, however, lies not in the fact that they reflect reality, but rather in our misconception that they do. Clifford argues that photographs offer themselves to us as transcriptions of reality; we do not recognise that they are always one individual's interpretation of events.23 What the viewer is allowed to gaze at is a reflection of that which the photographer has chosen to depict out of a much larger process or context - that which the photographer thought significant.

Such visualisation and its purported relation to reality has, as many have pointed out, signified whole cultural shifts. As Susan Sontag notes, "a society becomes 'modern' when one of its chief activities is producing and consuming images, when images that have extraordinary powers to determine our demands upon reality and are themselves coveted substitutes for firsthand experience." 24Sontag's latter point about substituting for experience also applies in the sense that visual images, with particular reference to photographic images, have certain suggestive qualities upon our memories. When we, for example, view an image of a historical event that we never attended, we refer the image to our memory bank and store it as a canonised reflection of the depicted event. Visuals become handy reference tools for our memories, which after all remember in images rather than 'text'. The ever-growing popularity of photography since its conception in 1839, resulted in an exponential growth in the production of photographs.25 The command that images hold on our perceptions thus continuously present the mind with a series of predigested memories that can be applied directly to 'imageless' (that is textual) information that has been read and stored. Such memories, no matter how compelling, will nevertheless be false - based on reality from within the lens, as opposed to reality beyond the lens. Neither is Celia Lury in Prosthetic Culture completely at ease with the power of the photographic image: "The manipulation of photographic images and ways of seeing make it possible for memories to be implanted in the individual while others are stored in 'banks'".26

It was these manipulative capacities of the photographic images upon the human mind that made it ideal weaponry in the Namibian war. The propagandistic qualities of the medium instigated a war within the war, being fought over the 'hearts and minds' of a divided Namibian population.

Viewing a War: The Gaze of Apartheid

Being gazed upon can be pleasurable or painful: there are times when we enjoy being watched or photographed or filmed by others, but there are also times when being watched or recorded makes us feel acutely embarrassed, persecuted even.27

Racial stratification was inherent to the apartheid system. The basis of the system was a hierarchy, largely determined by skin colour and cultural belonging. The prefix/code on the former South West African ID cards was but one example of this crude division of people, categorising 'Whites' for example under the code 01, Basters 02, and Herero 06. The practical enforcement of apartheid entailed strict measures of control, resulting in civil paranoia and silence. Rumours and fears of the South African 'secret police' solidified a situation of paranoia well-known in other absolutist states, such as the USSR (KGB) or Nazi Germany (Gestapo), and especially in Namibia's urban areas. It need hardly be said that the situation in the north of the country, where the military presence of both SWAPO and South Africa was severely felt, was far more intense.

The SWAPO or pro-SWAPO rallies of the late 1980s were often filmed. Whether or not pictures of the crowds were actually used is unsure, but the sheer psychological effect of such a gaze of apartheid would be intimidating, at the least, and, to quote Walker and Chaplin, 'painful', 'embarrassing', and 'persecuting'. The National Union of Namibian Workers (NUNW) '435' rally (see Figure 2) of October 1988 was filmed by the security police, who in turn were shot by a photographer from The Namibian, giving them a taste of their own medicine.

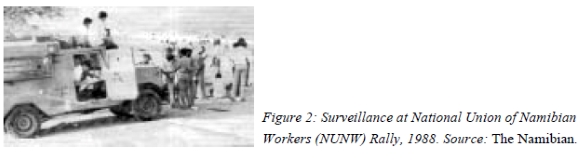

In text and images of PERGAMUS and PARATUS, apartheid ideology was continuously present. The photograph in the May 1987 edition of PERGAMUS was symptomatic of the envisaged hierarchies. The image is of Oshiwambo-speaking SWATF conscripts, known as the 101 Battalion, at a parade in honour of their visit to Cape Town. The battalion stands at attention, facing the left hand side of the image, looking out of the frame. The camera has been positioned at a higher level than the soldiers, making the soldiers look less significant than if they had been depicted from below. Although this could have been a motivation for the elevation of the camera, it would have been ulterior to the presence of Prime Minister P.W. Botha, who, seated behind the SWATF soldiers, is seen gazing down at the military exercise. The photographer, who sought to keep the parade and the group of VIP onlookers inside the frame, was therefore forced to stand higher in order to capture the full bravado of the event. What becomes central to the reading of the picture is thus not primarily the positioning of the camera but rather the positioning of the Generals (Malan and Geldenhuys) and the Prime Minister in relation to the 101 Battalion. In designing the picture, the photographer described the gaze of the onlooker and thus emphasizes the relationship of power between the visiting 101 Battalion and the high-ranking figures representing the apartheid system. The condescending stare of P.W. Botha establishes the obsequiousness of the Namibians in the image, and thus serves a somewhat sinister purpose of upholding the illusion of white superiority in the mind of the viewer.

An almost tragi-comic example of the apartheid gaze is found in the August 1987 edition of PERGAMUS. A picture of a group of white senior citizens, paying attention to a white officer whilst a black Namibian soldier is kneeling in front of them (Figure 4), is followed by the caption: "The senior citizens were very impressed by the explanation given by Cmdt.[commandant] Godfrey Tawse of 2 SWA Specialist Unit, on the mechanism and combat efficiency of the RPG7 rocket launcher".28

It seems comical that the group of smiling elderly faces were lectured on the "mechanism and combat efficiency" of a deadly weapon in the most casual manner, as were they being given a tour of a cement factory or the like. The kneeling pose of the black Namibian is puzzling. He is dressed in full combat gear, and sits with his back to the camera.

Further down on the page, the photograph is accompanied by a further image, showing more 'impressed' senior citizens - this time at a very vivid display consisting of two members of the Alpha Company (Koevoet) demonstrating platoon patrol formations (Figure 5). As in the former picture, the soldiers are kneeling and wearing full combat gear. The gaze of apartheid is in effect. The old lady observes the Koevoet soldier, not as one human being regarding another, but with some degree of distance; she is viewing an exhibit, not a person. Whether or not there were white conscripts on display is another matter - if so, they were not depicted in PERGAMUS. The voyeuristic gaze of white upon black, in the two images, was largely a continuation of much older ethnographic photographic trends. The old lady calmly stares at the two black upholders of the 'white man's burden', her voyeuristic feast undisturbed by the human exhibits.

Returning the Gaze

In The Combatant of August 1986, a picture features three armed SADF soldiers standing inside a homestead in northern Namibia. Facing them is a civilian standing with his back to the camera. Unlike the prearranged images commonly found in the different media of the time, this image contains a tension that would have been hard to orchestrate by a photographer. Resembling a scene from one of Sergio Leone's 'spaghetti' westerns, the photograph projects a gloomy atmosphere: silence before the storm, or the prelude to a 'showdown'. A power-gaze can be read from the image. The most obvious reading of this power-gaze relates to the aggravated stare of the three SADF soldiers who are facing a 'civilian'. Their seeming superiority in terms numbers (three against one), and their intimidating military stance favours a reading of the image whereby the 'civilian' is naturally seen as submissive. And yet, an alternate reading of the image possibly reveals a different interpretation. The facial expression of the 'civilian' is not disclosed in the picture, neither fear nor anger. We cannot therefore assume that the 'civilian' is submissive, facing the SADF presence. Rather, the roles are reversed. The photographer was positioned behind the civilian, aligning the viewer with him. By the placement of the viewer on the side of the 'civilian' the viewer of the image will unconsciously side with the 'civilian' in returning the pugnacious stare of the soldiers.

The two parties are divided across an imaginary line - the apartheid divide? The subconscious alliance between 'civilian' and viewer, personified by the photographer, proposes the three SADF soldiers as antagonists and the 'civilian' as protagonist. The 'power' of the soldiers fades and leaves them pitied rather than feared, somewhat reversing the military power-gaze. This translation of the image gains momentum in the fact that the picture was published in a SWAPO journal where the reader would automatically have viewed the soldiers as the enemy and the civilian as the ally. For the readership of The Combatant, the picture described a 'oppressed' and 'oppressor' scenario, assisting itself in the maintenance of an already present antipathy towards the South Africans. For SWAPO/PLAN, the image further disclaimed South African absolute military superiority in the mind of the viewer of the image.

'Shoot to Kill'

In Namibia the natural wonders and the 'exotic' inhabitants have been portrayed time and again by both domestic and foreign image-hunters. Namibia is a photogenic country, and images of big empty spaces and nubile 'natives' have clad the walls of museums and galleries throughout the world. Professional image-hunters have aesthetically depicted the Namibian 'hidden' beauty in tourist guides, calendars, magazines, and the like. In the private sphere, you will find the amateur 'hunters', who have targeted Namibia for their adventure holiday. Loading, aiming, and shooting on a perilous photographic safari, their trophies come in glossy and mat pocket size formats. The most impressive trophies are framed and hung on the wall, much in the manner of game hunting.

Where there are trophies there must be casualties, and when someone 'shoots' somebody is 'shot'. As has been pointed out by various scholars dealing with the photographic image, the terminology surrounding the medium is not unlike that of guns. In The Colonising Camera, Paul Landau notes that: "the discourse of outdoor photography and the physical technology of camera and film both drew on European hunting and gunnery".29 Susan Sontag takes the analogy a step further in saying that: "Just as the camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated murder".30 Sontag's statement is strong and provokes the question: who are the victims of the photographic gaze?

Previous mention of the relationship of power between Palgrave and his subjects was given as a dignified exception to an otherwise derogatory gaze on Africa and Africans by 'employers' of the camera. Traditional ethnographic depiction of that time sets up different layers of victimisation. Whether or not the kapteins and leaders in Palgrave's pictures were victims of the 'gaze' is debatable, but surely they became victims of the photographic image in the course of the disturbances and later European colonial aspirations caused by the large influx of European settlers that followed in the wake of Palgrave and his pictures. There are therefore different levels of 'victimisation', or creating victims, in the uses of the photographic image.

When referring to victims in a war, one inadvertently thinks of the dead and wounded. These are the physical casualties inherent to the nature of war. Surprisingly though, in the publications referred to in this article (especially The Combatant), only few pictures relating the physical carnage and atrocities of the war can be found.

In June 1987, The Combatant published a collage of images depicting the atrocities of the South African war-machine - a haunting and graphic composition. The most dominant and penetrating photograph showed a dead body huddled amongst the debris of a traditional homestead (Figure 7). The left leg of the body was twisted appearing to be broken at the hip. The caption read: "A victim overrun by a Casspir vehicle." 31

The collage was unusual for The Combatant in graphically showing the explicit nature of the war. Throughout 1984 -89, not a single image of dead PLAN soldiers appeared in the journal. Rather there was an emphasis, textually and visually, on the 'crimes' perpetrated by the South African military in Namibia. Omitting martyr-type pictures of PLAN fighters was most likely the result of seeking to encourage rather than discourage fighters going to war. Letters from readers imply that the journal was read inside Namibia, and for the sake of prospective new exiles, the same reasoning would have applied. As such, there was probably an editorial decision to portray civilian victims and not military martyrs. Furthermore, The Combatant also did not portray dead South African conscripts. Surely there must have been casualties on the SWATF/SADF side, and one would think that such images would have been admissible in the propaganda war, to show Namibians that the war was in fact not the unfair contest that South Africa claimed it to be. John Liebenberg, who was a leading Namibian war photographer, recalls:

In the eighties, I remember, the only picture you ever got to take [in Angola] were from moving cars and hotel rooms, and when you went with SWAPO it was the picture of the refugee or of a SWAPO crèche. Our visa applications in the eighties and early nineties only read 'to photograph the starving children of Angola'.32

One reason for the lack of 'action' images could have been that SWAPO was fighting the war using guerrilla tactics. The demands for high levels of manoeuvrability in the hit-and-run operations would have made the added burden of a photographer inconvenient and indeed a liability. SWATF/SADF, with their thoroughly planned 'operations', on the other hand did have accompanying photographers at various stages of the war (for example Hooper's Koevoet 'adventures'). Pictures taken of such operations (usually in their aftermath) were displayed unabated in both PERGAMUS and PARATUS, and mostly described dead and wounded PLAN fighters.

Operation 'Sunday Suit'

In PARATUS, a 'special report' from October 1985 describes a 'captured terrorist' receiving 'medical attention'. The 'terrorist' is lying in a diagonal pose surrounded by SADF/SWATF soldiers. The picture is large and commands the reader's attention (Figure 8). In front of the 'terrorist' a South African soldier is seemingly attending to the passive patient. Notably, the 'victim' has been granted protection by the magazine in the shape of a black line covering his eyes and thus his identity - a gallant gesture perhaps? In the foreground of the image, the hair of a black Namibian is seen. This otherwise unidentifiable figure is holding a rifle and is part of a circle of SADF/SWATF soldiers surrounding the 'captured terrorist'. The black Namibian presence was of importance. Both PARATUS and PERGAMUS carried constant reference to the black and white counter-insurgency cooperation. Such emphasis on black Namibians fighting against SWAPO was given for twofold reason: as part of the 'hearts and minds campaign', and also to emphasise the South African (mis)conception that SWAPO was regarded a feared terrorist organisation by the Namibian people.

Reading the above assumptions into the image is perhaps an extreme and over-analytical reading of the picture. However, one would not think it accidental that, out of a presumably large range of photos taken in the course of the operation, PARATUS chose that photograph over other perhaps more action-packed images. Gavin Ford, who wrote for PARATUS in the 1980s, further testifies that "photographs were always highly posed",33 indicating that photographers were commissioned by the magazine to arrange certain given scenarios. It becomes evident that the choreography was taken to yet another level when looking in the sister magazine PERGAMUS. Here the same image was used to illustrate a similar textual description of 'Operation Sunday Suit', albeit in an original uncropped version (Figure 9). Cropping the original image could have been done for a number of reasons, although such technique is usually applied to achieve either an aesthetic improvement of balance and compositional qualities or a manipulation of the communication of image content.

The new version of the image is far more revealing. The black line, that had been used to hide the PLAN fighter's identity in South African-based PARATUS, is now gone. Why? PERGAMUS was published in Namibia, and yet the identity of the 'victim' was exposed to a readership that was much more likely to recognize him than in the case of PARATUS. The previous protective gesture becomes somewhat hollow. When looking at the unedited picture it is difficult to tell whether the PLAN fighter was in pain, or if he in fact was dead. The accompanying text claimed that he was shot in the ankle, and still it does not look like he was receiving medical attention, and certainly not to that part of his body.34 If he was indeed dead, the black line covering his eyes would more resemble the Catholic practice of closing the eyes of the dead. The eyes are symbolic of our 'life-force', and by hiding this section of the PLAN fighter's face, his condition is equally obscured from the viewer.

'Facts and pictures', as PERGAMUS headed an article dealing with the same operation, allowed more explicit images than its South African counterpart. 'Operation Sunday Suit' was illustrated by four photographs - two of which showed dead PLAN fighters being searched and filmed. This candid use of photographs, as opposed to PARATUS, is not altogether surprising. The Namibian readership was far more involved in the war, emotionally and physically. It would therefore have been difficult to hide the graphic reality of a war that for many Namibians was part everyday life - an all to vivid reality. In South Africa the illusion of a sportsmanlike war 'game' would have been far easier to uphold.

In the 'Operation Sunday Suit' images, many levels of victimisation exist. The physical injury sustained to the PLAN fighter, who is, of course, the victim of a South African bullet, is the most clear-cut instance of victimisation in the picture. But, in line with the shared semantics of camera and gun, his victimisation is also manifested by the marksmanship of the several photographers viewing him. Because of his state of passivity - having been shot (dead?) and surrounded by the enemy - the PLAN fighter is forced to surrender himself to the photographer and the readership, without any influence over his own representation. While the frame of people around him was being orchestrated by the photographer, who could localise a narrow context of his own choice, the 'victim' would have had little choice - if alive - but to accept his predicament. Repetitive infliction of 'camera-fire' was shooting him, exposing him, and humiliating him as a trophy of war. The feeling of utter humiliation is painfully apparent in the submissive, empty stare of the 'victim', who does not look into either of the two cameras, nor at the threatening eyes of the hostile crowd that encircles him. Further victimisation was effectuated by the manipulation (as above) in the privileged space of the editing room, in which tools such as captioning, cropping, and page lay-out were readily available for the 'victimiser'.35

The photograph published on January 20 1989 turns the role of the victim upside down. The picture is taken by a reader of The Namibian and shows a member of SWATF extending his hand to "disinterested residents" of the north, asking for their forgiveness (Figure 10). The soldier is keeping his distance as if he is aware of the imaginary line between him and the 'residents', which in the frame of the picture is effectuated by a white wall that almost cuts the picture in half. The entire crowd of people appear to be ignoring the soldier, as if he is not there. The only ones to have eye contact with the SWATF soldier are the viewers of the image; as if he is asking for their forgiveness, rather than the 'residents' who are oblivious to his presence. The time factor is crucial to the reading of this picture, as this was a point in time when the political climate was changing and the implementation of Resolution 435 seemed imminent. In this light, the SWATF soldier becomes a victim - a victim of the circumstances of the time; a prodigal son regaining his senses, returning home.

The Innocent Bystander

In The Namibian, which published its first edition on 30 August 1985, visual descriptions of the war were much sharper. Whereas war images in PERGAMUS and PARATUS related mostly to the South African operations inside Angola, The Namibian had full-page photographs of atrocities and bloodshed on a frequent basis. The editor of The Namibian Gwen Lister notes: "In those days we used some very graphic and horrible images of what the SADF did and the atrocities they perpetrated in northern Namibia, and on the people themselves."36

The focus of many of the pictures dealing with the war was directed at its impact on the public in the war zone, known locally as 'the North'. Photographs of people in the North often portrayed them as victims of the political situation, and they were typically depicted showing mortars, scars, wounds, and other physical reminders of a war being fought all around them. These kind of photographs conveyed the notion of 'the passive bystander', in as much as they described the impact of the war on a civilian population, struggling to lead a normal life in a place and time marred by the insanity of war.

'The innocent bystander' was, per definition, a victim. The victimisation of the 'innocent bystander', however, came in different forms. In the August 1985 edition of PARATUS, under the heading " Vir hierdie kommandolede is geen opoffering te groot" ("For this platoon no sacrifice is too great") an image of a SADF soldier speaking to the 'locals' appears. The soldier, who is wearing sunglasses, is placed in the foreground of the picture with three black Namibians. In the background the Casspirs are loaded with SADF men, which gives a more threatening atmosphere to the otherwise peaceful scenario of people conversing. According to the text, the operations of the time is a good opportunity to communicate with the ' plaaslike bevolking' ('local population'). Gavin Ford recalls that:

[A] characteristic of articles was that they had to portray 'winning the hearts and minds' of the people. In fact, this was the only direct propaganda brief. This was of prime importance to the then SADF, not only in print, but also in word and deed. With guerrilla activities abounding, allies had to be made of the rural people in [the] then SWA. They were dubbed PBs by the Defense Force ('Plaaslike Bevolking') or in English LPs ('Local Population').37

The deliberate attempt by the SADF to portray the ' plaaslike bevolking' as allies, however, created new victims. As mentioned in an earlier section of this paper, the time was one of interpersonal distrust bordering on a national paranoia of sorts. The 'spy-phobia' was apparent on both sides of the war. In Angola, Lubango claimed its victims, and likewise in Namibia the interrogation rooms where kept busy. Pictures such as the those in PARATUS and PERGAMUS were therefore endangering their subjects. Whereas the white soldiers, in the light of the 'propaganda brief', would have done their duty in trying to win 'the hearts and minds' of the people, the black Namibians in the picture where in fact at risk. Being pictured in conversation with the 'enemy' could at the time easily have resulted in the label of informer and collaborator, with the risk that such labelling bore. And yet, in this case all is not as it seems. On further inspection of the photo, one of the supposed 'victims', who is in fact holding a SWATF motorbike, is exposed. Rather than being the representative of the 'plaaslike bevolking that PERGAMUS dubbed him, this individual is, in fact, already a 'convert', a SWATF employee. This deception does, however, not undermine the previous claim of attached danger to the 'non-white' depicted in the apartheid-friendly media. Indeed it seems likely that reluctance to pose for this picture by the ' plaaslike bevolking', resulted in the recruitment of a SWATF employee in the fabrication of this 'hearts and minds-style' picture.

By contrast, images of the 'innocent bystander' were rarely found in The Combatant, which related a far more positive and pro-active view of Namibians united in the face of oppression.

The Bloodless War

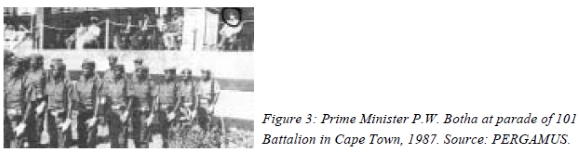

The glorification of war and combat is a phenomenon that is hard to come to terms with, especially when the human implications of war are taken into account. In war, the truth is always multifaceted and complex. However, this is not necessarily the case when it comes to war photography. Photographs reveal less than they conceal, and by offering the viewer easily consumed bona fide 'evidence', the camera can create victims, villains, and heroes on a piece of photographic paper, as well as in the mind of the viewer. In The Combatant June 1984, a haunting photograph of three PLAN fighters standing in silhouette adorns the front page (Figure 12). Later in the same year the image was reused, this time standing next to a poem:

They are simple but sharp and lethal

Impending their way is extremely mortal

They move like phantoms

Towards sons of hoodlams (sic.)

Those who robbed and ate up their bread

Let them have a reason to dread

Let them know that fighters fear no charms

They talk with guns and make you feel

They are fighters for freedom

They pull, they throw, they launch, they guard

And shoot their way homewards.38

Without attempting a shallow analysis of the poem, the overall point seems apparent from the rhetoric. The juxtaposion of heroic prose and heroic pose creates a somewhat romanticised and idealised image of PLAN. This is further substantiated in the upward angle of the photograph in question. Underscoring the grandeur of these larger than life figures, the images are very effective visual symbols of PLAN's heroic struggle against the 'sons of hoodlums'. The photographic technique applied to achieve the silhouette effect adds another dimension to the heroic image, leaving the soldiers faceless and monument-like in their petrified posture.

SWAPO was a liberation movement, encompassing the wide population of Namibia who wanted to change the status quo. And as such the ring around the movement was tightly shut. Very little information about issues such as the Lubango 'detainees' leaked from within the ranks of the movement. War is nasty, in whatever shape, but for not surprising reasons The Combatant continually displayed their romanticised image of PLAN and its fight against the South African regime. The Namibian, which was "committed to the international peace settlement for Namibia", also did not carry many pictures of PLAN fighters, except if they had been caught or killed. As such the images of heroic PLAN fighters were produced remorselessly as counter-propaganda to the image of the communist terrorist that was being portrayed by the media 'friendly' to the South African Defence Force.

Romantic visual descriptions of the war were also apparent in PARATUS. In the July 1987 edition, the front-page image describes a 'troopie standing against the sunrise/sunset in front of an army tent. The picture has an air of safari about it, delivering the sympathetic contemporary white South African viewer a mental image of 'the great outdoors' and depicting the war as more of a game hunt than the deadly game it in fact was. One can almost hear the shrieking of the cicadas or smell the morning dew. The notion of the 'game' is emphasized in the caption "Steeds Kampioene/Still Champions" printed at the bottom of the page. Again, the silhouette technique is applied evoking a sense of a greatness in the romanticised depiction.

Much like the omission of bloodshed and carnage in PARATUS, PERGAMUS, and The Combatant, these positive, 'toothless' photos serve to cloak the violent, brutal, and disturbing reality of warfare. Instead, the war was consciously recounted through heroic descriptions without bloodshed. On the question of creating heroic textual and photographic imagery, Gavin Ford explains: "The unwritten brief to in-house journalists (who were national service-men 'NSMs'), was to write articles in a spirit of aggrandisement, somewhat trumpeting the virtues of the military."39

Subsequently, the vast majority of images in PARATUS and PERGAMUS dealt with medal parades and anniversary 'bashes'. This self- imposed image was a necessary precaution to convince the fighting troops about the validity of their murderous venture, and also to uphold the illusion in civilian society that conscripted relatives would not be coming home in body bags. Liebenberg notes along the same lines: "Not one picture exists of a young white conscript or as a matter of fact any SADF troop lying dead on the battle fields of northern Namibia or Angola. Imagine the impact it would have had on the South African public."40

The importance of a bloodless war has been seen as an underlying theme in many of the images used here. It is therefore surprising that censorship was not equally effectuated on textual and visual descriptions of the fighting. In The Combatant there was a clear division between the allowed level of explicit imagery in photos and text respectively. The restrictions imposed on photography were apparently not applied to textual description:

We must continue to hit them [enemy troops]. I do not want to see a single fired bullet transfixing the soil harmlessly. Every bullet must run through the belly and head of a racist soldier.41

Moreover, a fixed space was allocated in The Combatant to a section entitled "News From The Battle Field". This section was, more often than not, void of visual imagery. When visuals were used they were usually drawings of raised fists (Figure 14), or neutral, non-threatening photos from inside Namibia. The text, however, would have more precise references to PLAN attacks and action, not omitting use of violence: "June 25, 1986 ... PLAN forces attacked and set ablaze a home guard base of puppet Andreas Kandume 110 KM West of of Oshakati. Three Koevoet thugs were killed and five others seriously wounded".42

The use of visual images was consistently non-violent in SWAPO's military publications, consisting of the same medal parades and anniversaries as those practised in the South African magazines. Exclamations of military prowess were almost part of a competition external to the physical conflict, the point being to intimidate the opposition and impress one's own by showing heavy armament and an inexhaustible number of combat-ready troops.

De-constructing the heroic image

In the less militaristic The Namibian photos of soldiers were not always flattering. The image appearing on November 4 1988 observes a very different, much less heroic, pose of the soldiers, who desperately attempt to hide themselves from John Liebenberg's extended gaze. These are the villains of the time. These SWATF soldiers know that the tide is turning, as do the readers of the image.

Such an image would surely not have appeared few years prior to its conception. The reversal of fortunes, now gives the photograph's audience a chance to return the power-gaze of apartheid South Africa, ridiculing them for their shame. As such, the image stands in stark contrast to propagandistic, heroic images of noble soldiery to which Namibians were relentlessly subjected.

On October 7 1988 another bold mockery of South African military prowess appeared. The picture displayed a SADF soldier pushing a pram at the Windhoek Show, dressed in uniform and armed with a rifle (Figure 16). Had the picture featured in PARATUS and PERGAMUS it would surely have been used to depict the human face of the ' troopie', but in The Namibian, the victory against apartheid is celebrated in ridicule of the soldier, whose 'de-heroicised' appearance, gun and pram, makes him laughable.

Except for the above style of images, photographs deconstructing the soldier-hero myth were rarely published. The least biased portrayals of the war were probably found in private collections, taken by the soldiers themselves, depicting a different side of the war:

I do know that the police themselves, and army members, who were present when a lot of SWAPO insurgents were killed would take photographs with cigarette butts stuck up the insurgent's nostrils, and things like that. These pictures were of course not made public.43

Once again, such images would not have fit the bill of the heroic 'troopie', in spite of the reality they reflected. Perhaps the perpetual silence and the heroic role imposed on the troops themselves played a part in the psychotic behaviour of these men who were not being held accountable for the most cruel of human acts committed whilst 'serving' their country. The average 'troopie' was in his late teens or early twenties at the time he was stationed in the north of Namibia.

Depicting Atrocities

One of the most famous exponents of war photography was Robert Capa, especially known for his depiction of the Spanish Civil War. His picture entitled Death of a Loyalist Soldier, describing a soldier being shot as he is running down a hillside, became one of the classical images of war-torn Europe in the middle of the twentieth century. The Spanish Civil War was short-lived compared to the twenty-three years of war in Namibia, little less than fifty years later. And yet, when one has to think of an equally definitive image, a symbol, of the Namibian war, the task seems overwhelming. Two of the people interviewed for this article, however, did refer to a particular image that made a deep impact on them.

For Gwen Lister it was the photograph of a body strapped on a Casspir:

We had a number of reports about SADF soldiers parading the bodies of SWAPO insurgents on their Casspirs. We didn't have the evidence ... the military continued to deny that this was happening, until finally one young man managed to get a photograph of a body strapped to the side of these Casspirs ... We printed it big on the front page.44

John Liebenberg comments that:

The photograph [Body on Casspir] became a strong propaganda tool for the pro-SWAPO lobbies in Europe and helped to fuel the funds they needed to collect for SWAPO. It became the symbol of the ruthlessness the forces operated in. No words could ever describe this scene of the body flung carelessly over the Casspirs, and as was the practice until then it could just be denied by the armed forces.45

The horrific picture was taken in 1987 and demonstrated the immense power of the image, both as evidence and in shaping peoples perceptions of the war. Even for people who did not see this image with their own eyes, the impact was emotionally and intellectually disturbing - "if this could happen, then what else was happening in the silenced war, where war reporting like 'Koekies vir troepies were the order of the day?"46 The body on the Casspir was a thousand times more effective in destroying the myth of the soldier-hero that had been so carefully constructed by the controlled media of the time. This image exposed with deep-felt horror the fratricide perpetrated in the North. An extra irony was added in the fact that the tireless design and choreography by the professional army journalists could do little to counter the effect of this image taken by "a young man in the north" - who took a simple picture by the side of the road but which had a profound impact.47

It has earlier been argued that the image by itself is a powerless medium. It is our interpretations, relative to our own subjective cognition, that gives the image its power. The same image viewed in different journals would have had different interpretations attached to it. Textual and visual images are read with a pre-directed state of mind, so that the SADF 'troopie' would have related The Combatant differently than a SWAPO cadre. A.P. Foulkes points out that "its [propaganda] recognition or supposed recognition is often a function of the relative historical viewpoint of the person observing it".48

But an image such as the picture of the body on the Casspir was of such a nature that even pro-South African viewers would have had to 'raise their eyebrows'. Another example of such a visual is the famous photograph from the Vietnam War, depicting a naked child running towards the photographer in deep agony from her napalm wounds. Even Americans who favoured the War would not have like to view Frank Johnson's disturbing photogaph that stood in such stark contrast to the gung-ho style of reporting by the pro-war media loyal to the US government. The photographs by Capa, Johnson, and "a young man in the North" in three different ways (the injured, the dying, the dead) described the human realities during war. The penetrating effect of these images, standing out among the many images of war, is not so much description of war itself, but representations of the people caught in the war. Capa's image supposedly49 froze the moment of one individual's transition from life to death; Johnson's photo exposed the results of US chemical warfare, de-glorifying their Vietnam War venture; and the man in the North described not only the death of a PLAN-fighter, but also the war-psychosis suffered by SADF and SWATF soldiers in perpetrating and displaying horrific killings.

Conclusion

Photographs constitute valuable 'sources' for historians. They often contain details that no words have described. However, as much as these pictures pose as reality, they are subject to interpretation and manipulation. It is this duality surrounding the photograph, and the way in which this was utilised by the opposing sides in the Namibian liberation/Bush War, that has been the focal point in this article.

In the 1980s the camera presented a powerful weapon in the 'propaganda war' that was being fought alongside the actual war. Differences were many and sympathies few between opposing sides in the war. But, when viewing photographs from the Combatant, PARATUS and PERGAMUS it becomes difficult to differentiate the three; all contained depictions of romantic life in the army, medals and parades, military prowess, and bloodless battles. This was surely not the 'reality' of the war. Although ideological opposites, apartheid and anti-apartheid forces used the photographic medium in much the same manipulative manner, and, one suspects, towards the same aims.

The Namibian played its mind-games more candidly; its declared aim was to promote the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 435, a stance it promoted by exposing apartheid and its disciples to the world. The 'realities' of the war, or at least the realities encountered by journalists and photo-journalists, were therefore laid bare in the paper. The war, however, was for the most part being fought far away from the newspaper offices in Windhoek. Few 'realities' of carnage and trauma were therefore reported, rendering PARATUS, PERGAMUS and The Combatant, as well as other biased organs of SWAPO or apartheid South Africa, the custodians of a truth that was layered with romantic war imagery. These visual and textual accounts of the war have undoubtedly imposed themselves upon different sections of collective memory and awareness, with little to counter them as long as the silence is perpetuated, and as long as this war remains unspeakable.

1 W. Steenkamp, Borderstrike (Durban, 1983), 3.

2 Thanks are extended to Dr Jeremy Silvester, Professor Musambachime and Dr Christo Botha of the History Department at the University of Namibia; to Gavin Ford, Gwen Lister and John Liebenberg; and to Dr Patricia Hayes for their input and support in the preparation of this article.

3 See, for example, Nda Mona: I Have Seen (Pakleppa, On Land Productions, 1999).

4 J. Berger, Ways of Seeing (London, 1972), 8.

5 Another issue that should be commented upon is the racial terminology adopted in the publications cited. I found it very awkward to describe Namibians according to their skin colour (black, white or coloured). In present-day Namibia such rhetoric has tended to be replaced by reference to language proficiency, for example Oshiwambo-speaker or Afrikaans-speaker. But apartheid-era terms in text and captions used here with their emphasis on skin colour relates specifically to the mind-sets of the time,, on different sides of the apartheid divide.

6 Wolfram Hartmann et al (eds), The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History (Cape Town, Windhoek and Athens OH, 1998), 2.

7 Paul Landau, 'Hunting with Gun and Camera: a commentary' in Hartmann et al (eds), The Colonising Camera.

8 Stefan Sonderling, Bushwar (Windhoek, 1980); Jim Hooper, Koevoet! (Johannesburg, 1988), and Willem Steenkamp, South Africa's Border War 1966-1989 (Gibraltar, 1989).

9 Brian Harlech-Jones, A New Thing?: The Namibian Independence Process, 1989-1990 (Windhoek, 1997); John Saul and Colin Leys (eds), Namibia's Liberation Struggle: The Two Edged Sword (London and Athens OH, 1995); Lauren Dobell, War by Other Means (Basel, 1998); Siegfried Groth, Namibia - The Wall of Silence (Wuppertal, 1995); Peter Stiff, The Silent War (Alberton, 1999); SWAPO's Their Blood Waters our Freedom (Windhoek, 1996), and Anne-Marie Haywood, The Cassinga Event (Windhoek, 1994).

10 Interview with Gwen Lister, 11 October 1999.

11 Ibid.

12 "With the exception of The Namibian newspaper and church publications ... all other newspapers ... do not only distort information and give false accounts of events, but are always full of propaganda against SWAPO and other patriotic groups" (The Combatant, Sept. 1987, 13).

13 Email interview with Gavin Ford, 21 October 1999.

14 Cited in J. Cock and L. Nathan, War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa (Cape Town, 1989), 90.

15 Susan Brown, 'Diplomacy by other means - SWAPO's Liberation War' in Saul and Leys (eds), Namibia's Liberation Struggle, 37.

16 According to Herbstein and Evenson, "Off duty, members of Koevoet wore T-shirts proclaiming 'Murder is our business - and business is good'". Dennis Herbstein and John Evenson, The Devils Are Among Us: The War for Namibia (London, 1989), 64.

17 Peter Stiff, Nine Days of War(Alberton, 1989), 216.

18 Herbstein and Evenson, The Devils Are Among Us, 71.

19 PARATUS, August 1985.

20 Within hours of the official United Nations cease-fire, substantial fighting broke out with over forty dead on the first day. See Harlech-Jones, A New Thing?

21 Hartmann et al (eds), The Colonising Camera, 11.

22 Liz Wells (ed), Photography: A Critical Introduction (London, 1997).

23 Cited in Rhoda Rosen, 'The Documentary Photographer and Social Responsibility', De Arte, 45, April 1992, 7.

24 Susan Sontag, On Photography(London, 1979), 153.

25 "The inventory started in 1839 and since then just about everything has been photographed". Ibi'd., 3.

26 Celia Lury, Prosthetic Culture: Photography, Memory and Identity(London, 1998).

27 J.A. Walker and S. Chaplin, Visual Culture: An Introduction (Manchester, 1997), 97.

28 PERGAMUS, August 1987, 4.

29 Hartmann et al, The Colonising Camera, 151.

30 Sontag, On Photography, 14.

31 The Combatant, June 1987.

34 Present at the event was Willem Steenkamp, who in his South Africa's Border War included an image taken from behind the downed PLAN fighter. The caption reads: "The team commander stands astride the wounded man after saving his life by running to him, forcing the over-excited soldiers to stop shooting at him". (Steenkamp, South Africa's Border War, 137).

35 PARATUS, October 1985, 13; PERGAMUS, October 1985, 2.

36 Interview with Gwen Lister, 11 October 1999.

37 Email interview with Gavin Ford, 21 October 1999.

38 The Combatant, October 1984, 25.

39 Email interview with Gavin Ford, 21 October 1999.

40 Email interview with John Liebenberg, 6 October 1999.

41 Dr Sam Nujoma, The Combatant, January 1984, 15.

42 The Combatant, June 1986, 29.

43 Interview with Gwen Lister, Windhoek, 11 October 1999.

44 Interview with Gwen Lister, Windhoek, 11 October 1999.

45 Email interview with John Liebenberg, Johannesburg, 6 October 1999.

46 Ibid.

47 The photograph, taken in the village of Ondobe, appeared in The Namibian of 18 January 1987.

48 A.P. Foulkes, Literature and Propaganda (London, 1983), 8.

49 Debate still surrounds this Spanish Civil War death in front of the camera.