Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.30 n.1 Cape Town 2004

Hermanus Matroos, aka Ngxukumeshe: a life on the border

Robert Ross

Leiden University

Hermanus Matroos, also known as Ngxukumeshe,1 was born, probably in the last decade of the eighteenth century, presumably somewhere in western Xhosaland.2 He died on 7 January 1851, shot dead in the streets of Fort Beaufort while leading an abortive attack on the town at the beginning of what came to be known as Mlanjeni's war. He lived his life in the first half of the nineteenth century on the increasingly well-defined border between the Cape Colony and Xhosaland, and he was a well-known and increasingly important figure in the exceedingly complicated politics of warfare, land, labour and identity which characterised the western frontier of Xhosaland throughout this period.

By those who establish them, borders are generally meant to separate one piece of territory from another. However, there are always opportunities for those who are able to operate on both sides of a border, at least as long as they can enjoy the tolerance, witting or otherwise, of those who might have the power to seal the border. For most of his life, Hermanus was able to play the complicated political games which this entailed with consummate success, exploiting the chances given by his position as an interpreter. As a consequence he was able to set himself up as a Xhosa chief - though he had no royal blood - under colonial patronage and within the colony. The indications are that he pursued goals within, primarily, a Xhosa value system, and that the Xhosa in general realised what he was doing and tolerated it. The British, on the other hand, generally did not understand him, and to the extent that they did, they could no longer tolerate him. This was eventually to lead to Hermanus' s death.

Hermanus's career is surprisingly well documented, but that very documentation is necessarily problematic. The contemporary information about Hermanus and his settlement all derives from Europeans, and in particular from colonial officials.3 This has the consequence, normal enough in African (and indeed much European) history, that those things which he was careful to conceal from the Europeans can only be known on the basis of surmises, whether by contemporaries or later historians. Both may be wrong, as both may be based on premises which are not acceptable to other analysts. Indeed, Hermanus himself was well aware of the advantages of being culturally incomprehensible. He prospered because he understood the Xhosa better than any Englishman, and perhaps the British better than any Xhosa. This allowed him to create the space within which he could operate, but, for historians, it makes the reconstruction of his life peculiarly problematic. He did not live within any one cultural idiom, but, as a professional interpreter, he lived by translating from one to the other, and by exploiting the one for the other. His biography, which I will attempt to present here, is driven by that continual straddling between the colonial and the Xhosa worlds, even though, I would argue, for the man himself the Xhosa world and its values were paramount.

This straddling had indeed begun before his birth. His father had been a slave in the Colony,4 but had managed flee to the Xhosa, escape being sent back, as occasionally happened when Xhosa leaders wished to bargain with the colonists, married a Xhosa woman of the amaJwara clan, and became a subject of Nqeno of the Gqunukwebe. In his youthful years, Hermanus learnt Dutch, perhaps from his father and certainly while working on a farm in Zwager's Hoek near Somerset East, which he did for some years. No explanation was ever given for this course of action, and apparently none was every needed. During this period he learnt to speak Dutch 'with the fluency and accent' of the Khoikhoi, as well as to drive wagons and to act as a general farm servant.5 At this stage he acquired the name, Hermanus Matroos, by which he was primarily known to the colonists. Later in his life, he could also speak a certain amount of English, although the only recorded sentences of his testify to a thick accent, or at least an inability to pronounce interdental fricatives ('th'), not uncommon in those who have not been brought up speaking the language, but perhaps exaggerated for comic effect by the English reporter.6

His stay in colonial society, as a farm labourer, was not permanent. He was able to make use of his connections to the Xhosa to escape from the quasi-bond-age in which farmers in much of the Eastern Cape held their labourers. He thus returned to the Xhosa, and was initiated, and acquired the name Ngxukumeshe - 'he who is in the vanguard'. He then went to live with Ngqika, who could well make use of his talents, which were much more than merely linguistic. Most of those who met him, later, were impressed by him. James Read Junior commented on his ' shrewdness and tact' ; a commission under the chairmanship of Robert Godlonton, to which I will return, noted his reputation for 'personal bravery and activity' as well as, again, for his shrewdness. Lieutenant-Colonel Napier, who met him in 1847, commented on the pleasure which Hermanus's conversation gave him. None of these men had any particular reason to approve of Hermanus, and indeed both Read and Godlonton many to condemn him. He clearly became a man well able to impress those who met him, as well as being a physically imposing individual.7

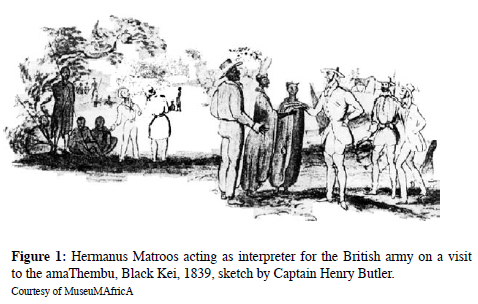

Interpreter

At least from 1819 onwards, Hermanus was employed as an interpreter in the dealings between Ngqika and other Xhosa, on the one hand, and the colony, in particular the British military, on the other. He was for instance one of those sent by Ngqika to request the help of the British in the conflict with Ndlambe which led up the Battle of Grahamstown. During that conflict he was used as an interpreter by Colonel Henry Somerset, beginning a relationship which would last for more than thirty years and which seems, on perfunctory evidence, to have been the friendship of two men whose outlook on life was in many ways remarkably similar.8 From then on, he moved between the British and the Xhosa with regularity and a degree of ease. The British at times thought they were employing him, and eventually they naturalised him as a British subject; Ngqika and his successors elevated him to the status of mpakati, or councillor, a status which his descendants held into the twentieth century.9 Where his true loyalties lay is difficult to say. Probably, they were only to himself. The only alternative explanation is that he was playing a long game as a Xhosa double agent within colonial society, a career worthy of a John le Carré novel, but not really plausible.

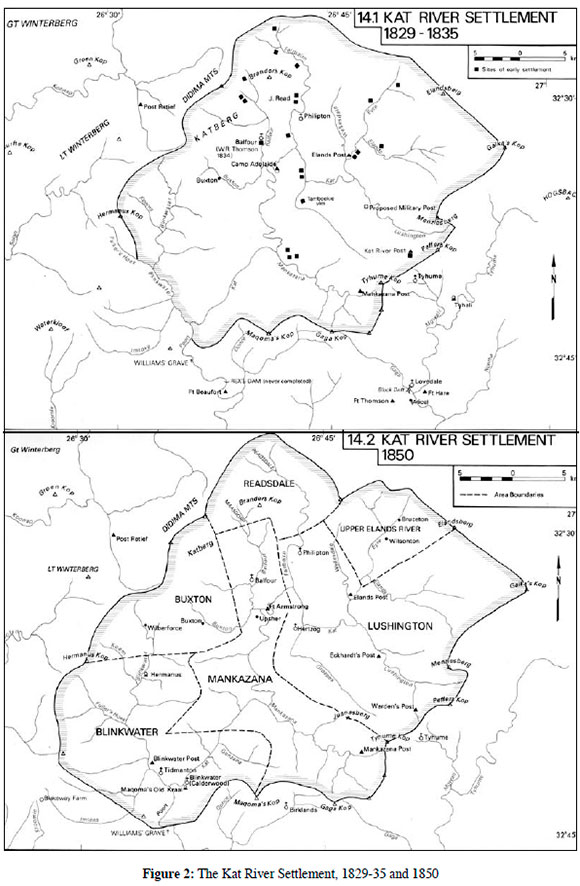

However this may be, what is clear is that by the end of the 1820s Hermanus had ceased to live in Xhosaland proper and had moved into what was then designated as the 'Neutral Territory', the region east of the Fish River which the British had designated as an empty buffer between themselves and the Xhosa after the 1819 war, but which they were presently to occupy themselves and to plant the Kat River Settlement in. This is said to have been the consequence of a conflict with Ngqika, though the substance of the disagreement is never made clear. It may merely have been that Hermanus, who already had political ambitions, was looking for a place where he could establish himself as an independent homestead head - and in the course of time gather a more substantial following around him. At any rate, during that period, he came to live in the Kat River valley, in the near vicinity of Maqoma, who quite certainly had left his father Ngqika with the intention of expanding his power base.10

When the British expelled Maqoma from the valley in 1829, Hermanus did not accompany him, and was not forced to do so. Later it was claimed that he had betrayed a plot on the part of Maqoma violently to resist their expulsion, and had thereby saved the lives of Colonel Somerset and the other officers.11 There was clear enmity at this stage. Maqoma attacked Hermanus's homestead in April 1829, and removed all his cattle, a month or so before the British drove the former over the border. Therefore, Hermanus was able to argue that his life would not be safe in Xhosaland, and that it was imperative that he remain in the colony. The local British officers, particularly Somerset, supported him in this, even though the Governor, Sir Lowry Cole, ordered him to be dismissed from colonial service and expelled across the hills into Xhosaland proper. Cole based his decision on his apparently untrustworthy interpretation, and perhaps on the fact that Hermanus had not warned the British of Maqoma's attack on the Thembu. However, Hermanus had been accompanying Colonel Somerset to the Fort Willshire fair at the moment of Maqoma's raid, and therefore, Somerset claimed, could have had no foreknowledge of it.12

For the next years attempts were made to find some alternative farm where he could settle, for instance in the neighbourhood of Theopolis in the Zuurveld, or further west in the neighbourhood of Uitenhage or George. These attempts all came to nothing, in part because Hermanus was unwilling to move his cattle into the tick-invested sourveld around Theopolis.13 The alternative that was offered to him was a location to the north of the Winterberg, but this too did not suit him.14At any rate, Hermanus was able to remain in the Kat River valley, more specifically in the middle Blinkwater, in what is today the Mpofu game reserve. By 1832, he had sixteen men, with their dependents, among his followers.15 This was in breach of the understanding by which he had been allowed to remain in the colony - at least the British interpretation of that understanding, which may not have been that of Hermanus himself. While the British thought that they had only given him permission to maintain a 'suite' of a few persons as cattle herds, he had assembled around himself

a numerous party of Caffres, Hottentots, Bushmen, Bechuanas &c, and although he has been informed repeatedly of the conditions that were imposed upon him, and to which he had assented, he continues to harbour a numerous band of persons of the above description ... The many losses sustained by the Farmers in the vicinity of his location, and the constant intercourse maintained between his people and the Caffres warrant the suspicion that the former afford facilities for the commission, if they do not actually commit, the depredations complained of.16

These sorts of complaints formed the basis on which the civil authorities wanted to have him expelled from the colony, and temporarily drove him out of the Blinkwater valley in 1833. For a while he found a residence near the Tyume, and resisted his return to Xhosaland because, as he informed the British, 'having been in the service of the Colony and occasionally employed in tracing stolen cattle in that country, the chiefs would put him to death if he placed himself in their power.' The Civil Commissioner of Albany doubted that this was the case, as Hermanus apparently had previously made a number of visits into Xhosaland, some of quite long duration.17 He did manage to remain in the colony for the next year or so and in the run-up to the Frontier War of 1835 - Hintsa's war - Hermanus was again used as an interpreter by Somerset, in his dealings with Maqoma.18 The war ensured the revival of his fortunes, despite the temporary depletion of his herds. He claimed to have lost 270 head of cattle and 19 horses, to direct Xhosa raiding, to starvation while they were congregated around what was later to be named Fort Armstrong, and on commando, while his men lost 56 cattle and 10 horses in the same way.19 Then in the war itself, Hermanus was continually active on the colonial side. The Governor, Sir Benjamin D'Urban wrote of him that he had not been unfaithful and treacherous, an accusation which had been apparently made of him by the Civil Commissioner of Albany, Donald Campbell, but rather that he 'has shown an excellent example to the Kat River people to fight gallantly in their own defence, giving very judicious advice, leading them, personally, shooting Caffers with his own hand and committing himself thereby to the extreme hostility of the Caffre tribes.'20

This was written because Hermanus had been arrested in the early days of the war, on suspicion of collaboration with the enemy. Nevertheless he continued to work with the British, both as a fighter defending his own homesteads and primarily as an interpreter in dealing with the Xhosa. He was thus present when Hintsa came into the British camp, and is said to have warned the British, presumably on the basis of conversations he had overheard, that the Xhosa king was planning to escape.21 Certainly his relations with high-ranking British officers, built up over the course of the war and previously, can explain why it was that in the immediate aftermath of the war he was confirmed in the possession of his land, and given a double-barrelled gun by the Governor.22 This came despite the protests of Sir Andries Stockenstrom, who was in this not merely the protector of the Kat River settlement, which he had initiated, but also a landowner in the vicinity. An additional explanation is that there was a carve-up of state land between the Blinkwater and the Koenap among the officials concerned with the Kat River, and the confirmation of Hermanus would make it easier to prevent protests, or at least divert them. It was explained to him, so it was later claimed, that he was allowed to hold the land conditional on his good behaviour, and would not be allowed to have more than ten followers with him.23 'Good behaviour' was not defined, then or later, and was always in the eye of the beholder; the number of Hermanus's followers, on the other hand, grew apace. At any rate, he received 7,379 morgen in the Blinkwater valley, with good grazing in the valleys, and sour grass on the heights, together with much timber.24 He was to remain there for the rest of his life.

Colonial chief

The Blinkwater river rises in the Didima mountains and joins the Kat shortly above the Poort, the narrow pass where the river passes through the hills on its way to Fort Beaufort. In general, the Blinkwater has cut a much sharper valley than the other tributaries of this river system, and there is little of the meander-cut bottom land which formed the basis for the irrigation systems of the rest of the Kat River settlement from its foundation in 1829 onwards.25 Even in the upper reaches of the river, near the settlement that in the nineteenth century was known as Wilberforce, and now as Upper Blinkwater, relatively little agriculture had been possible, though the arable land is now so infested with exotics as to make it difficult to reconstruct - let alone resuscitate - the land use patterns.26Lower down, where Hermanus came to live, the land was, and still is, heavily bushed. The Blinkwater Commission wrote in 1850 that:

It may be described in brief as a congeries [sic] of densely wooded kloofs, many of them penetrating deeply the surrounding mountains, which are lofty and precipitous, though covered, where not encumbered, by bush, with fine grass. The high road to the Winterberg and Tarka divisions passes through the valley; the huts occupied by Hermanus and many of his people being within sight of it, but as extensive, torturous and densely wooded, it will be evident that the best means of concealment are presented and corresponding difficulties opposed to the detection of cattle thefts when traced to this neighbourhood.27

The result of this geography was that Hermanus had the opportunity to move cattle across the border to the Xhosa, and was regularly suspected of doing so. What was of course necessary for this was that he had resurrected his relationship with the Xhosa leaders, from whom he could reasonably be supposed to have alienated himself by his conduct both before and during Hintsa's war.

This became easier with the establishment by Maqoma, then regent of the Rharhabe, of a large cattle post in the lower Blinkwater. Hermanus was able to rebuild his relationship with Maqoma, which had been ruptured a decade or so earlier. In 1837, Hermanus married a 'near relative' of Maqoma's, and even if a considerable bridewealth was involved, this marital alliance indicates that the two were prepared to cooperate.28 Hermanus - perhaps in this context he should again be called Ngxukumeshe - clearly considered himself subordinate to Maqoma. A year later, Maqoma fined Hermanus seven head of cattle, four goats and an axe, though for what offence it is not clear.29 Hermanus was also at times prepared to take some of Maqoma's cattle and put them to pasture on his land, certainly during the drought of 1842.30 At this stage at least, he was accepted as a subject by Maqoma, and himself accepted that status.

During the years that separated Hintsa's war from the War of the Axe, Hermanus was building up his power as a Xhosa headman, or minor chief, allied to the Royal House, in the person of Maqoma, but with a clear independent power base deriving from the right he had acquired to live west of the Tyume. This allowed him to bring a considerable following together. There was a considerable turnover among his supporters. In 1842, the magistrate of Fort Beaufort, M. Borcherds visited Hermanus armed with a list of those who his predecessor, Capt. Armstrong, had allowed to accompany him six years before. Originally Hermanus had had sixteen followers, but of those one had died, four had returned to Xhosaland, two had settled in Fuller's Hoek without permission from the Government or anyone else (except perhaps Hermanus himself) and one was simply absent. Nevertheless, by this stage he had forty-eight men with him, all of whom bar four are described as having been granted permission to reside in the colony by Hermanus, not by Government.31 It was a most varied group, in terms of ethnic origins. Precisely half were described as Xhosa, four as Gona, seven as Thembu and thirteen as Mfengu. Of these twelve (including two of those described as Mfengu) had been in the colony for ten years, thus since before Hintsa's war, and another eight - none of whom were Mfengu - seem to have come across during that war.32

By this stage Hermanus was rich in cattle and wives. He owned 260 head, just about 43% of those in the settlement as a whole. This made him one of the richest Xhosa men, with a level of wealth equivalent to that of major Xhosa chiefs. The census of the Ngqika in 1848, admittedly after the devastations of the War of the Axe, gave the highest cattle holding of a homestead - let alone an individual man - at 288.33 He also had four wives, and while all of the men listed in this census were married, possibly a consequence of male mortality during the wars, only one of the others had four wives and twelve others had two. Between them, they had 198 children, seven of whom, plus at least one adult son, were Hermanus's. It was evidently a flourishing community, in its way.34

Part of the reason for the turnover in the Blinkwater settlement was that Hermanus regularly accused his underlings of sorcery against him. In 1836, he was involved in a conflict with two of them, described by the British as Goana and Goonta, who he had allowed onto his farm because he believed them to have been his friends and 'well disposed towards the British'. However he later came to think that they had attempted to poison him because he had 'shot several of their friends during the war'. Captain Armstrong, at that stage British Justice of the Peace in Fort Beaufort, felt that he had to remove them from the Blinkwater in order to maintain the peace, not because he believed that they had actually made an assassination attempt in this way, but because he was convinced that they had threatened to engage in the 'supposed practice of sorcery' against Hermanus, and he wanted to make an example in this way against the threat.35 Whatever the truth of this, Hermanus continued to express his nervousness, not altogether surprising given the delicacy of his political position, by having his followers smelt out for 'having bewitched him and caused his sickness', in this case an attack of rheuma-tism.36 Indeed he is described as having believed that the swelling of his legs was caused by 'chameleons, which some enemy had by power of witchcraft placed in them.' More generally, he believed in a 'Supreme Being, and in an Evil One, but allotted more power to the latter than to the former, - that creed suited him best.' The other persons of the Trinity were not within his comprehension.37

Colonial incomprehension of items of Xhosa culture were just as great. Europeans never understood the logic of the relations which Hermanus may or may not have maintained with other Xhosa who had come to live in the wooded valleys running down into the Blinkwater. In colonial theory they were squatters, in illegal occupation of the land. Therefore their dwellings should be burnt and they themselves expelled from the Colony back into Xhosaland. This was necessary not just to maintain the desired spatial organisation of the population but also because they were thought to be responsible for the stock loss which regularly occurred in the rich lands to the west of the mountains.38 The magistrate at Fort Beaufort regularly felt called upon to clear away those who, by his reckoning, should not have been where they were. Thus in the winters of both 1842 and 1843, Borcherds, the man in question, led parties of the Cape Corps through the Blinkwater valley, burning homesteads which had been established by Thembu, Xhosa, Mfengu and Gona, while demanding of the Khoi Veldcornet of Buxton, Andries Botha, that he too performed the same task throughout the area under his control. He was not always successful in his actions, as in 1843 he had to note that

The whole of these people appear to have had notice of my approach, for I found all the goods removed out of the huts, the men fled into the bush, and only a few old women and children left near the huts, so that I took no prisoners. Wherever I found any women sick, I left huts for them to remain in, until they are well enough to travel.39

It is however by no means implausible that Hermanus himself encouraged the settlement of those whom the colonial officials wanted to remove. In 1837 an officer of the British army wrote of this region that:

I have always regarded the location of Hermanus as the most unhappy circumstance which could befall this part of the Frontier, not from any known dishonesty on the part of the man himself but because his presence there is and may be used as a pretext for the wandering visits of others, and it is quite enough to create alarm and disquiet among the English residents that they should be subject to visitors of this description - against whom being friendly Caffres, it would I suppose be improper to act with the rigour warranted to be employed against other Caffres and then comes the difficulty of distinguishing between the vagrant Robbers of Caffreland and the actual followers of this privileged Caffre occupant of lands within the Boundary.40

The understanding which a British army officer had of the cultural logic of Xhosa politics is certainly suspect. However, it is not implausible that he judged correctly what was happening, namely that Hermanus was using his position as a protected client of the British to build up a princedom based in the Blinkwater valley, and that all, or at least many, of those who came to live in the steep kloofs did so with his permission and owed him fealty, in exchange for protection (and perhaps cattle in loan). There is no way of demonstrating the truth or otherwise of this conjecture, but it would, I believe, explain much of what happened from the early 1840s up to 1851.

This process, if that is what was going on, was interrupted by the War of the Axe. Wars must always be very problematic for people like Hermanus, who flourish on the ambiguity of their social and political position. They are forced to choose where their loyalties lie, at least temporarily. Hermanus chose the British. Maqoma, committed as he was to the Glenelg treaty system which the British were unilaterally discarding, did not fight to the utmost but rather surrendered to the British as soon as he decently could.41 Things would be different five years later.

Hermanus's actions in the War of the Axe are not well documented. In the beginning, Sir Andries Stockenstrom, called back from retirement to command the burgher militia, had initially rejected Hermanus's offer to join that force with all his men. This offer was declined because, as Sir Andries later commented, 'he should not cut the throats of his countrymen on account of the Queen of England, under my auspices.' Sir Andries did not trust Hermanus, at least in retrospect, and claims that the Kat River Khoi did not either. If they were wise, by this stage the Kat River Khoi did not trust anyone. Despite this, other British officers were prepared to take Hermanus into their service. He and his men fought, and he interpreted, in the British army for most of the war, under Captain T.C. Minter, until he was cashiered for embezzlement, under Charles Lennox Stretch and finally under Col. Henry Somerset.42 The British, however, parsimonious and perfidious as ever, did not provide Hermanus with either the pay or the booty, which he had been expecting. It was an act of bad faith they were to regret.43

In the years after the War of the Axe, Hermanus's efforts to set himself up as a semi-independent Xhosa chief intensified. To do this, it may be imagined that he employed the full range of strategies available to a Xhosa leader, although such matters as his marriages - except to Maqoma's relative - or the lending out of cattle as a means of cementing hierarchical relationships are not recorded. He had certainly been able to acquire a substantially larger following than before the War. In 1848, the settlement he led contained 87 men, 122 women and 288 children. The total number of cattle had decreased, probably as a result of the war, to 468, and remarkably only 54, or 12 per cent, belonged to Hermanus himself, this in contrast with 43 per cent some six years earlier. This might suggest that he was involved in various loan arrangements to cement his leadership. On the other hand, he might also have made a conscious decision to transfer his wealth into another form, as the number of his wives had risen from four to twelve in the intervening years.44

In addition to the strategies of accumulating women and cattle so common in southern Africa, Hermanus had begun to perform those rituals and produce those events by which a Xhosa leader demonstrated his power. Even before the war, they had attracted the attention and disapproval of those Khoi who had taken on board the full message of the mission, such as Arie van Rooyen, an elder of the church which the Rev. Henry Calderwood had established at Lower Blinkwater who was later to become the first Khoi to be ordained within the Congregational (LMS) church. In 1842, Van Rooyen wrote to the British authorities in Grahamstown that:

Hermanus is in the Colony and he is still busy with Xhosa things ... If he is a Colonist, what does he have to do with Xhosa things, and if he is a Xhosa why does he not go into Xhosaland. By this deed, Hermanus shows that he is an enemy.45

After the War of the Axe such matters became even more of a political act. In January 1848, the British Governor, Sir Harry Smith had harangued the assembled chiefs as to how, in the new province of British Kaffraria, progress would be achieved through the imposition of English customs and habits.46 These included not just clothes, ploughs, schools and trade, but also the abolition of lobola and related matters. It was thus provocative, at the very least for Hermanus to hold what was described as a 'Gieko' only two month later. The description which the magistrate gave of this ceremony was that

It commenced at Hermanus's own kraal, by the assembling of all the principal men who have wives of their own, certain other men of lower rank called 'Dindaar' (Dienaar - Constables) are appointed to slaughter fat cattle and to cook, it is also the duty of those men to go and collect all the unmarried girls from the other kraals from 12 years old and upwards and after the girls are all collected, they are divided amongst the men who are assembled on the 'Gieko', several huts are made use of in which they lodge many together and if the girls are not sufficiently numerous one girl has to serve the purpose of many masters - and in this manner they live for several days on a week till the cattle appointed for the supply of feast are all devoured, after which time the girls are allowed to go home and the party disperses for a few days or a week when it again begins.

The second 'Gieko' was held at the kraal next above Hermanus's and so on up the valley to the others. At these 'Giekos' between 20 and 30 young girls were made use of, many of whom had been taught in the Missionary School to read both Kaffir and Dutch. Hermanus allowed or put in two of his own daughters, in the Gieko, young girls of about 14 years of age, one of whom can read Kaffir and Dutch.47

As a result of this information, Hermanus was informed that as he had been 'recently practising barbarian habits, his conduct is unsatisfactory to the Governor,' that he was in the colony entirely on sufferance and that if he misbehaved in the future the British would 'send a military force and drive them [him, his followers and other Africans in the area] out of the Colony.'48

Colonial offensive

This threat was part of a concerted campaign against the Kat River settlement in general and the inhabitants of the Blinkwater in particular. It was conducted in the period between the War of the Axe and Mlanjeni's war and was in part responsible for the outbreak of the latter, or at least for the course which it took. This assault was made possible by the unprecedented dominance which the Cape conservatives held under the administrations of Sir Henry Pottinger and Sir Harry Smith, both of whom were highly dependent upon, or at least under the influence of, the Colonial Secretary John Montagu, together with the 'family compact' of like-minded officials in Cape Town, on the one hand, and of the circle around Robert Godlonton in Grahamstown, on the other.49 The latter in particular had a long-standing hatred of the Kat River settlers, which was heartily reciprocated.50 The appointment of members of the Biddulph and Bowker families, noted Eastern Cape conservatives, as the first two magistrates of the newly constituted Stockenstrom district, which was largely coterminous with the Kat River settlement and the Blinkwater, gave greater sharpness to the campaign. T.H. Bowker, for instance, wrote that 'such is the difficulty of penetrating into the natural mysteries carried on in those strongholds of savageism, [sic] the beehive hut that nothing but the removal of these people into neighbourhoods where they can be under a salutary supervision will ever break up their inveterate propensi-ties.'51 Certainly, where there had once been a school, and reasonable hopes on the part of the missionaries for conversion, this had disappeared, and the house where divine services had been held had fallen into dilapidation.52 A few children did however go to the LMS school in the lower Blinkwater.53

The challenge had come about because of the considerable increase in the population under Hermanus and in Fuller's Hoek in the aftermath of the War. When Bowker, together with Commandant Groepe, visited Hermanus, he noted that

A considerable quantity of land has been cultivated in the Kaffir manner and large crops of Kaffir corn, pumpkins and Kaffir melons have been gathered there this last season, so much so that many Kaffir women have come from Kaffirland to the Blinkwater after Kaffir corn, which they carry to Kaffirland in their usual way upon their heads.54

In a year of good rains, it was evidently a flourishing settlement. At this visit, the magistrate estimated the number of cattle at around 1500, including some 300 in the kraal nearest to Hermanus's own dwelling, three times more than in the census in the same year. Whether Bowker overestimated what was present, or whether the cattle had been hidden out of sight when the census-takers arrived can unfortunately not be determined.

What exactly was happening in Fuller's Hoek is also difficult to ascertain. What is incontestable is that in the period after the War of the Axe a considerable number of Africans - presumably Xhosa and Mfengu in the first instance, but probably including a number of Thembu - came to live in the wooded kloofs running up into the mountains. This was in contravention of the original order, as the land was to be given out to Khoi in terms of the extension of the Kat River settlement.55 At least one of those who had been granted land there, in return for his original plot which had been confiscated when Fort Armstrong was built, never took up his land because of the proximity of Hermanus, at least so his son claimed during the compensation hearing after the Rebellion.56 When the magistrate visited it in 1848, he commented that, although land had been granted to Gonaqua57 since 1837,

At present there are but 5 families of Gonas left. Fullerskloof extends from the junction with the Blinkwater about two miles in a south-westerly direction ... in it we found six kraals and above 50 huts inhabited by Kaffirs, certain of whom belonging to Botma [Bhotomane] were in the colony when the war broke out in 1846 and have since squatted there. When Macoma went to Algoa Bay [during the war] several Kaffirs, six or eight with their families, were sent back from Grahamstown. These also squatted there. The others have all crept in at various times and are interbred with the Gonas who seem to be the nucleus of attraction.

In the various kraals and huts there cannot be less than 300 head of cattle and 30 men besides their families - only four of the Kaffirs who came into this place during the war are employed. They are living with Andries Klaas and his family but are not contracted. The rest of the numerous Kaffirs and Gonas squatted in this kloof are living in their own ways and customs and spend their time in idleness and hunting and in herding cattle.

I ascertained from some of the Colonial people living in Fuller's Hoek that many strange cattle are frequently there and also that several hundred kaffirs of all ages and sexes left Fuller's Hoek a day or two previous to my arrival taking their route into the Colony.58

Away to the north of Hermanus Matroos's settlement, there were also a number of settlements of people whom the colonial rulers called squatters. In 1850, the Blinkwater Commission visited the area, the Kama, which they described as a basin, ten miles in diameter 'ribbed by kloofs and steep ridges, covered with the finest pasturage, while some of the higher lands are faced to their summits with forests abounding with fine and useful timber.' They found it 'little more than a harbour for Squatters - Kafirs, Tambookies and Gonahs - who live in a state of unmitigated barbarism and indulge without control in all the brutal practices inseparable to that state.' They had cattle and hunting dogs, and, to the suspicious members of the Commission, 'it was impossible . not to conclude that they subsisted by preying on the property of the colonial farmers.'59

What is not clear is how far these individuals looked to Hermanus as their leader. Perhaps they saw him as a representative of the Rharhabe chiefs, with whom he had by this time made his peace, even if he on occasion pretended otherwise to British army officers.60 Certainly Hermanus was doing all he could to maintain his authority over those who had come under his control. This was manifested when the British introduced a quitrent of £1 for each man in all of what they considered the 'Fingo' communities, which can best be described as containing all those Africans (non-Khoi) living within the old colony, as opposed to the newly proclaimed province of British Kaffraria.61 Payments were few; despite a following of at least a hundred, only nine men paid quit rent in 1849 and five in 1850.62 The Rev. Henry Calderwood, once the LMS missionary at Lower Blinkwater (and in this capacity an adversary of Hermanus's) but by now the Civil Commissioner of Alice in Government service, commented that 'Hermanus seems desirous of living where he is, in all respects as an independent Caffre chief,' and that 'he does not seem to care so much about the demands made for money, as the fact, that if each man pays to Government, he would have as good a right to the Land as Hermanus himself.'63 For a man who had built his career as an intermediary, this was intolerable.

In the course of 1850, the colonial officials launched a concerted attack on the inhabitants of the Blinkwater. It was not for the first time. Burning the huts of the inhabitants of Fuller's Hoek, in particular, was a regular activity of the magistrate of Fort Beaufort.64 The attempt to assert colonial control over the area had begun with the appointment of Valentyn Jacobs as Veldcornet of the Blinkwater and Fuller's Hoek in 1848, taking responsibility for an area of land which Andries Botha, from Buxton, had difficulty in reaching with any regularity.65 It does not appear that this move had any particular effect. Things were rather different when the Government appointed a certain Mr. T.W. Cobb as Superintendent over the Mfengu in and around the Blinkwater. Cobb's task was to form locations among the Mfengu and Xhosa and thus provide a degree of order, according to colonial criteria, with enclosure of lands, the breaking of oxen to the plough or the wagon, and the encouragement of schools for the children. The inhabitants were to be active in the apprehension of thieves, and were to perform public works, notably road building. 'Witchdoctors' were banned from their settlements.66

In the event Cobb, who had been appointed in somewhat dubious circumstances67 and would be killed, perhaps murdered, in the course of the rebellion, claimed land in the middle of the Tidmanton commonage as his own. He then began impounding cattle which strayed across the unfenced boundary and charging substantial fees to have them released.68 The Khoi inhabitants of the lower Blinkwater continued to have complaints about the settlement of Mfengu and Xhosa in their vicinity.69 The colonial response was to attempt to sell the region to private, British settlers, thus depriving the Kat River settlers proper of a part of the territory which they believed to be theirs, and further antagonising the Africans in the kloofs. In the event, the sale came to nothing, at least till after the Rebellion, but the commotion was nonetheless substantial.70

The serious assault, though, came in the winter of 1850. The British finally decided on the criteria by which they should judge who was allowed to remain in the colony. Charles Brownlee, at that time British Commissioner with the Ngqika, had visited the Blinkwater and claimed that there were in principle three categories of Xhosa there, namely those who had arrived in the colony before the war of 1835, before that of 1846 and subsequently. Those in the first two categories had fought against their 'countrymen' and therefore should be allowed to stay in the Blinkwater or in some other suitable location, except for those 'who practice heathenish customs and who do not bear good characters.' The others should be removed, at least as soon as they had harvested their crops. According to Brownlee, it was up to the Field-Cornets to determine who belonged in each category.71

From 12 June 1850, the local officials moved through the Blinkwater to clear the region of those who, according to this categorisation, did not have the right to be there.72 There is a certain irony in their proceedings, as the actual work was done by a unit of the 'Kaffir police', almost all of whom would have fallen under Brownlee's third category and thus themselves have had no right to residence in the colony.73 This was done first in Fuller's Hoek, where fifty-seven huts were burnt, six hundred head of cattle and many goats secured, and over fifty women, together with their children, were herded together and brought down to the post. From there they were to be sent into Xhosaland. Others, who were said to be Hermanus's people, were sent to join him. The Gona, who could not be expelled because they had been born in the Colony, were to be brought down to the Lower Blinkwater and settled there under supervision, as they had formed the 'nucleus' of the settlement. Stringfellow then moved up to Hermanus's residence

where we found about seventy74 men assembled ... all of whom are represented by Hermanus to have performed good service in the war, and entitled to protection on account of good conduct. After calling over the list I inquired of Hermanus if he had anything to say, previous to my taking any further steps, when he complained of want of room for his people. Having reminded him that when complaints were made by the farmers against hunting parties of Kaffirs for trespassing upon their lands, that he had disclaimed any knowledge or connexion with them; and that he was only responsible for fourteen families. I requested him to account for the inconsistency now apparent from the present muster of his people. His silence induced me to address a few words to him in the presence of those assembled, upon which I took occasion to remark upon his want of good faith in several instances refused to [sic, presumably 'referred to'], and particularly in endeavouring to conceal his knowledge of the people in Fuller's Hoek or their pursuits. I impressed upon them the advantages enjoyed under a civilized government, the protection afforded to life and property, and the fine country allotted to them, and with respect to the complaint for want of space, I referred Hermanus to the great number of persons in the Blinkwater who professed to be his followers, and informed him that if he wished the removal of any person, now was the time. He expressed himself and his people satisfied.

Stringfellow then informed Hermanus of the necessity of the payment of quitrent for the Blinkwater residents, and told him to appoint headmen over each division of his followers, to 'watch their conduct and report to Hermanus when requisite, who would be held responsible to Government.'

While this meeting was going on, Davies was busy burning two Xhosa homesteads, one belonging to Mali, a follower of Bhotomane 'whom I knew in the war against us.' On the next day, he went on with the work, burning Xhosa homesteads over the boundary assigned to Hermanus's people to the south, and on the day after, a Sunday, he was joined by Bowker, the resident magistrate of Stockenstrom and moved through the hills to the north-west of Hermanus's settlement, 'where we found more of his people, burned their huts, and passed them over the boundary. These men were not present at the muster' held two days earlier. Hermanus protested at this, saying he had too little room, but that 'the men were his', and should not be sent to Xhosaland. He was then told that 'both his own and his men's cattle were liable to be put in the colonial pounds for trespass, if they were ever again found over the boundary of the land allotted to him and his people.' Others, in the Kume kloof, had already driven their cattle into Hermanus's land, but Davies and Bowker destroyed their huts. Then they moved across from the Upper Blinkwater to Buxton, and began to clear those who were living as the dependents of Andries Botha and the Khoi at this place. It was at this moment that the Xhosa police were heard - at least by Botha, but probably not by Bowker and Davies, neither of whom, it is safe to assume, understood Xhosa - to call out exultantly: 'Today we burn Botha out of the Blinkwater as he burnt us out of the Amatola last war.'75 Whether they had the same feelings towards Hermanus is difficult to say; certainly he had not played as prominent a role in the War of the Axe as Botha. In total, more than three hundred huts were burnt in the week-long campaign. 145 men, 350 women and an unknown number of children were driven off the land, together with nearly 2,500 head of cattle and 1,400 goats.

Subsequent to this expedition there was considerable criticism, particularly from the missionaries and from Sir Andries Stockenstrom, both of whom were primarily concerned to vindicate Botha. It was clearly a very heavy-handed operation, in which the British were quite unable to appreciate the relations of clientage which had grown up between the Khoi and those whom the British designated as Xhosa, or as foreign. It was certainly a time when the boundary between Khoi and Xhosa was even more porous, and uncertain, than usual.76 This is not the place to investigate in detail the charges against Botha, although it does seem clear that some of those expelled as Xhosa interlopers were as Khoi as he was, and had resided with him for many years. What is interesting in this context, though, are Bowker's comments on the communities he had brutally disrupted. He wrote that 'the whole of these immense establishments of "squatters" are but one joint stock company from the wily Hermanus to the wary and deceptive Andries Botha, and that nothing could be done by the one that the other was not almost immediately cognizant of.'77

This may have been true, and there was a homestead of one of Hermanus's followers on the erf of one of Botha's sons,78 although it is most unlikely that Andries Botha could have done much to prevent the presence of the Xhosa. However, Bowker was probably correct in his assumption that Hermanus had an interest in what was going on far beyond the confines of the farm which the British, with their love of tidy lines on maps, had granted to him. If it is assumed that he had taken on at the very least a watching brief for all the Xhosa, in the broadest sense of the word, who had come to live in the Blinkwater valley, and especially if this is thought to have been agreed between him and the Ngqika chiefs - and for this second assumption, I know of no evidence - then his subsequent actions become much more explicable.

Hermanus's next significant brush with the colonial authorities occurred some five months later when, in response to a petition from many of the leading landowners and others on the frontier, a Commission was despatched 'to investigate certain complaints and accusations made against the inhabitants living under the nominal Chief Hermanus.' This commission was led by Robert Godlonton, and included at least two of those who were themselves landowners in the near neighbourhood of the Blinkwater. Those whose huts had been destroyed by Stringfellow and Davies in Fuller's Hoek were said to have returned and to 'while away the day in listless idleness and the night in prowling the country.' As evidence for their claims they cited a local trader who had in the last two months purchased 500 hides, mainly from Africans living in Fuller's Hoek and with Hermanus. Most of these hides were not from cattle which had died in the drought, but 'were those of fine large oxen in good condition', and on occasion the brand had been cut out. In general, they considered that

If, in locating Hermanus within the colony, it had been the design of the Government to present to him the greatest temptation to illicit practices, and to the Frontier colonists the most insuperable obstructions to the detection of them, such object could not have been more completely obtained than by placing him in the country in which he now dwells, and leaving him there, as he is left, without any supervision or means of detecting and correcting those evils which might have been expected to arise amongst a people of barbarous habits, and who are so prone to dishonest and aggressive practices.

However, means had to be found not merely to punish Hermanus and his followers for the actions which they were supposed to be carrying out, and to threaten to turn him out of his land, but also to promote his self-interest in working with the Colony. At the moment, so it was said, 'he fortifies himself by closer amity with the Kaffirs, by increasing the number of his followers, and by more craftily planning his aggressive designs upon the Colonial farmers occupying the adjacent country.' There were already numerous rumours that his territory formed 'the chief rendezvous of a great many of those Kafir servants who have recently absconded from the desertion of the Colonial farmers and whose desertion has caused so much excitement and alarm throughout the country.' Hermanus himself denied having heard any such reports, but when confronted by the 'schoolmaster on his own homestead' who had read out paragraphs from the colonial newspapers to him on the subject, he admitted that he had heard, but pleaded 'a treacherous memory'. Whether this was happening, in November 1850, is difficult to say, and the Commission had to admit that in specific cases, the rumours were false. However, it seems more than likely that Hermanus was already making preparations for the war which was to come.79

Mlanjeni's war

There was another explanation for the supply of hides to the local trader which the Commission did not mention, and almost certainly did not appreciate. During the spring of 1850, the prophet Mlanjeni had been urging the Xhosa to slaughter their yellow and dun-coloured cattle as part of his campaign to purify the land and to root out witchcraft.80 Hermanus was among those who had visited Mlanjeni and had followed his call.81 He had perhaps by this time concerted the plans with the Xhosa chiefs for the attack on the Colony, which duly begun on Christmas day 1850.82 A disproportionate number of those who fought had been labourers or 'squatters' and thus were likely to have been in contact with Hermanus and his fellows in the Blinkwater.83

Hermanus's first act during the war was to request, and receive, a supply of arms and ammunition from the British in Fort Beaufort, an action which, to say the least, suggests a considerable level of chutzpah on his part, and total failure of intelligence (in both senses of the word) on that of the British.84 He then returned to the Blinkwater, where he began to collect all those he could around him. The Khoi could with difficulty defend themselves against Hermanus's actions, in part because they were heavily outnumbered and in part because magistrate Bowker, as one of his last acts before his dismissal, had confiscated three hundred guns.85Hermanus had 900 Xhosa under him, and he was able to press at least 90 Khoi to his service, despite the attempts of the L.M.S. minister at Lower Blinkwater, the Rev. Arie van Rooyen, to prevent this.86 Some of these, including one Isaac Isaacs, had been soldiers in the Cape Mounted Rifles, and refused to take part in the fighting, so that Hermanus was forced to hold them prisoner.87 Hermanus's force was joined not merely by Xhosa, who included some of the police who had burnt their way through his valley six months earlier but who now in their totality took their arms against the Colony.88 His camp had also attracted many men of Khoi descent, mainly from among the farm servants in the Winterberg89and elsewhere, but also a proportion of the Kat River settlers proper. Hermanus could thus serve as a focus around whom all the diverse, but nevertheless serious, grievances against the colonists could coalesce and create, at least temporarily, a united force.

Apart from the capture of a couple of wagons and the killing of their incautious (and apparently drunken) English owners, the first military action of the rebellion was an attack by Hermanus on a military post known as the Old School, close to Fort Beaufort on 30 December. This was followed up, on New Year's Day, by the capture of the fortified farmhouse belonging to W. Gilbert, one of the Blinkwater commissioners, near Fuller's Hoek. Gilbert had two small cannons to defend his dwelling, but these failed to protect him, and they fell to the lot of the rebels. Either here, or at the Old School (or just possibly on both occasions), Hermanus had his horse shot from under him.90 The cannon were carried to the rebels' camp in the Upper Blinkwater.

The next part of the plan was to attack and capture Fort Beaufort. This was to be done on the 7th of January. Two days earlier, however, William Goezaar and John Corner,91 two of the Kat River people who had been held captive by Hermanus, managed to escape and to reach the British missionaries in Philipton, with the news that an attack had been planned. The Rev. James Read Snr. then sent a letter to his old colleague (and adversary) Henry Calderwood informing him of the impending attack.92 The message was passed from Alice to Fort Beaufort, where the British were ready to receive Hermanus and his forces.

The attack began at 4.30 in the morning. It later transpired that this was a couple of hours earlier than intended, with the result that Maqoma, with a strong force coming out to the Amatola mountains, was unable to concert with those who had descended on Fort Beaufort from the Blinkwater. This may have been a question of impetuousness on the part of the rebel forces, not necessarily Ngxukumeshe himself (as it is surely proper to call him at this moment). Ngxukumeshe indeed seems not to have been part of the first assault party. On the other hand, it is possible that the attackers seized on a moment during which the ford across the Kat River at Stanton's drift had been left unguarded, as the sentries who had been posted there the night before returned to the church in town at first light without waiting to be relieved. The attackers however fired off shots unnecessarily as they approached the town, and thus roused the defenders before they could be overrun.93 Another description made closer to the time, but very possibly self-serving, claims that an Mfengu sentry at the drift let off warning shots.94

At any event, from that moment, Ngxukumeshe, somewhat incongruously wearing a blanket and a lady's black crepe bonnet, led an attack across another drift into the town, in an attempt to encircle the colonial forces. At the same time, counter-attacks by the town militia, by a substantial body of Mfengu and by a small party of British regulars from both the 91st regiment and the (Khoi) Cape Mounted Rifles, held the assailants in Campbell and D'Urban streets, drove down to Johnstone's drift and managed to outflank the attackers by crossing a bridge to the south-west of the town. The result was a complicated melee, which was only decided when Ngxukumeshe himself was shot dead, apparently by Mfengu.95There followed a rout. According to the British, no doubt exaggerating as such forces tend to do, they killed a hundred of the enemy, and, following up their victory back through the Poort to the north of the town, captured 2,000 head of cattle, many sheep, goats, horses and discarded weapons. In so doing they went all the way up to Ngxukumeshe's settlement in the middle Blinkwater, where they found, and no doubt looted, a goodly supply of furniture. In the course of so doing, they released a number of the old soldiers from the Cape regiment who had refused to join in the assault on Fort Beaufort and had been tied to trees in the Kat River, expecting to be executed should their captors prevail.96

Ngxukumeshe's body was laid out in the market square of Fort Beaufort under the market-bell and surmounted by the British flag as 'a warning to traitors, a spectacle full of encouragement for the honest, and of instruction to all,' as Godlonton's correspondent put it with classic colonial triumphalism.97 After a few hours he was buried below the military hospital. Rumour had it that the corpse was later grubbed up and devoured by the town pigs.98

Conclusion

It is always tempting to conflate the end of man or woman's life with the end of an era. Such a case could only be made for the death of Hermanus on the assumption that the failure of the Xhosa to capture Fort Beaufort doomed them to defeat in Mlanjeni's war and that it was the war and its aftermath which made the sort of life which Hermanus had been leading impossible in the future. Some sort of argument could be made for the first of these propositions, although it is as hard to see British accepting defeat in Mlanjeni's war as it would have been for them to do so thirty years later after Isandhlwana. The second proposition, though, does have more force. After the war, the British were able to impose their own order on places like the Blinkwater, and to divide it among themselves as sheep and cattle farms. The possibilities of developing a significant community of amaNgxukumeshe in the region would have passed, even had Hermanus lived, and remained on good terms with the British.99 He had been interpreter, landholder and also, though he was careful to conceal it, bandit chief. After Mlanjeni's war, none of these were occupations on which major black careers could be built.

1 My thanks to Andrew Bank, Carolyn Hamilton, Alan Lester, Fiona Vernal and the audience at the East London conference for comments on an earlier version of this paper.

2 He was said to be 56 in 1851. Robert Godlonton and Edward Irving, Narrative of the Kafir War, 1850-1851-1852 (reprinted Cape Town: C. Struik, 1962), 142.

3 Hermanus had few contacts with the missionaries, the other main source of information on the Frontier in the mid-nineteenth century, primarily because his interest in the main message which they propagated was, at best, minimal, and as a result he could not evince their sympathy.

4 I no longer believe, as I did when I wrote Cape of Torments: Slavery and Resistance in South Africa (London: Routledge, 1982), 87, that Hermanus was himself the absconder - although later Xhosa tradition has him as such. He seems to me to have been too much a Xhosa not to have been brought up as one, whatever else he may have been brought up as. Moreover, he would have been running considerable risks in his dealings with the Colony which began before the emancipation of slaves. There is never any suggestion of an owner wanting to reclaim him. For the Xhosa tradition, see Resurgam, 'Somana Hlanganse: Late headman of Kentani', Umteteli wa Bantu, 4 Aug. 1923; Nzulu Lwazi [pseudonym for S.E.K. Mqhayi], 'UNgqika', Umteteli wa Bantu, 20 April 1932. I owe both these references to Jeff Peires, for which many thanks.

5 J. Read, The Kat River Settlement in 1851 (Cape Town: A.S. Robertson, 1852), 13.

6 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 144. I assume that Noel Mostert (Frontiers: The Epic of South Africa's Creation and the Tragedy of the Xhosa People (London: Jonathan Cape, 1992, 1051)) is mistaken in his claim that the man whom the Rev. George Brown met at the beginning of Mlanjeni's war and who spoke perfect English, though disguised by much clay, was Hermanus. By 1851 there were many Xhosa with a good command of English, who might also have wanted to conceal their identity from a Scottish missionary. However it is not impossible that Hermanus could have been concerting with Maqoma on their further plans when Brown met them both on 28 Dec. 1850, and thus could have been the man who spoke English 'more precisely than I have ever heard any other native do.'

7 Read, Kat River Settlement, 13-14; Robert Godlonton et al., to John Montagu, 28 November 1850, in Proceedings of evidence given before the Committee of the Legislative Council respecting the proposed Ordinance 'to prevent the practice of settling or squatting on Government Lands' (Cape Town: Saul Solomon for the Legislative Council, 1851), 91 [this letter can better be described, and will hereafter be cited, as 'Report of the Blinkwater Commission, 1850']; E.Elers Napier, Excursions in Southern Africa (London: William Shoberl, 1849), vol. 2, 371-2. According to James McKay, Reminiscences of the Last Kafir War (reprinted Cape Town: Struik, 1970), 63, Hermanus was 'nearly six feet high, with a powerful frame.'

8 Somerset to Bell, 9 April 1829, Cape Town Archives Depot (hereafter CA), CO 366.

9 Read, Kat River Settlement, 15; H. Calderwood to Woosnam, 20 April 1847, CA GH 8/46; Resurgam, ' Somana Hlanganise'.

10 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 143; T.J. Stapleton, Maqoma: Xhosa Resistance to Colonial Advance, 1798-1873 (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 1994), 35-63.

11 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 143.

12 Bell to Somerset, 3 April 1829, CA CO 5111; Somerset to Bell, 9 April 1829, CA CO 366. J.C. Visagie, 'Die Katriviernedersetting, 1829-1853' (Ph.D. thesis, University of South Africa, 1978), 215.

13 Campbell to Bell, 31 August 1832, CA CO 2735; Campbell to Acting Secretary, 18 July 1834, CA CO 2749; C.C. Mitchell to Acting Secretary, 19 July 1842, CA CO 8462. The man onto whose farm he was to have moved, Henry Fuller, did receive land in the Kat River valley, specifically in what was to become known as Fuller's Hoek, a side-valley of the lower Blinkwater, below what is now Fort Fordyce.

14 Campbell to Secretary to Government, 12 July 1833, CA LCB 9.

15 Campbell to Bell, 31 August 1832, CA CO 2735.

16 Campbell to Lt. Col. England, 1 April 1833, 1/AY 9/19.

17 Campbell to Secretary to Government, 12 July 1833, CA LCB 9.

18 Statement made by Macomo ... at Fort Willshire, 28 Februaiy 1834, British Parliamentary Paper hereafter BPP) 503 of 1837, 111.

19 Armstrong to Hudson, 17 February 1836, CA LG 15.

20 Memorandum by D'Urban, 10 February 1835, CA ACC 519, 21.

21 Mostert, Frontiers, 724-6, 990; A.L. Harrington, Sir Harry Smith: Bungling Hero (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1980), 425, 70-2; Premesh Lalu, 'The Grammar of Domination and the Subjection of Agency: Colonial Texts and Modes of Evidence', History and Theory, vol. 39, 2000.

22 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 143.

23 Borcherds to Col. Sec, 25 May 1849, CA LCB 9; Borcherds had his information from a Mr. Bovey who claimed to have been present when the land was granted and the terms explained. Godlonton claimed that he was only allowed to have his immediate family with him, but - to put it in terms which Godlonton would not have recognised - the Xhosa definition of who belonged within this categoiy was much wider than that of the British. (Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 142-3).

24 W.J. Burns, 'Report on Lands situated between the Keiskamma, Chumie, Kat and Fish Rivers', February 1836, CA LCB 7; Stockenstrom to D'Urban, 18 December 1837, CA GH 8/5; Sir Andries Stockenstrom, Light and Shade as shown in the character of the Hottentots of the Kat River Settlement, and in the Conduct of the Colonial Government towards them (Cape Town: Saul Solomon, 1854), 13.

25 CA CO 2742: D. Campbell,-'Detailed Report of the Progress and Present State of the Settlement at the Head of the Kat River, District of Albany'; M. Winer and R. Ross, 'Kat River Settlement Historical Archaeology Project: Report on July 2000 reconnaissance trip', Unpublished report to South African Heritage Resource Agency, Cape Town.

26 My thanks to Rosalie Kingwill for her insights into this matter.

27 'Report of the Blinkwater Commission', 90-1.

28 Armstrong to Hudson, 15 August 1837, CA 1/FBF 6/1/1/1; Stapleton, Maqoma, 108-110.

29 Armstrong to Hudson, 18 March 1838, CA 1/FBF 6/1/1/2.

30 Borcherds to Hudson, 30 July 1842, CA 1/FBF 6/1/1/3. At the same time, Maqoma was hiring grazing land from Khoi in the Upper Blinkwater and near Buxton, in the Kat River Settlement; Borcherds to Hudson, 21 June 1842, 1/FBF 6/1/1/3.

31 One had been granted permission by Tyali, although what right he had to give such permission is unclear, at least to me.

32 See A. Webster, 'Unmasking the Fingo: The War of 1835 Revisited' in C. Hamilton, ed., The Mfecane Aftermath: Reconstructive Debates in Southern African History (Johannesburg and Pietermaritzburg: Witwatersrand University Press and University of Natal Press, 1995), 241-277.

33 J. Lewis, 'Class and Gender in Pre-Capitalist Societies: A Consideration of the 1848 Census of the Xhosa', Collected Seminar Papers of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, London: The Societies of Southern Africa in the 19th and 20th Centuries, vol. 17, 1992, 76.

34 Borcherds to Hudson, 30 July 1842, CA 1/FBF 6/1/1/3.

35 Statement by Hermanus, 27 September 1836, CA LG 385.

36 Borcherds to Hudson, 30 July 1842, CA 1/FBF 6/1/1/3.

37 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 144.

38 In the mid-1840s the farms of the KoenapVeldcornetcy, the region in question, had one of the highest average values in the colony. See R. Ross, 'Montagu's Roads to Capitalism: The Distribution of Landed Property in the Cape Colony in 1845' in Beyond the Pale: Essays on the History of Colonial South Africa (Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press, 1993), 58.

39 Borcherds to Hudson, 21 June 1842, CA 1/FBF 6/1/1/3; Borcherds to Hudson, 11 July 1843, CA 1/AY 8/93.

40 Memorandum 25 June 1837 by an 'officer of the 75th regiment' (name illegible), CA 1/FBF 5/1/2/1/2.

41 Stapleton, Maqoma, 138-141.

42 B. le Cordeur and C. Saunders, eds. , The War of the Axe (Johannesburg: Brenthurst Press, 1981), 101, 253. [ Links ]

43 Stockenstrom, Light and Shade, 17.

44 'List of Kaffir men, women and children residing with Hermanus Matroos', CA CO 2849; the alternative explanation is of course that Hermanus was able to hide most of his cattle from the census takers.

45 Arie van Rooyen to Hudson, August 1842, CA LG 442, cited in Visagie, 'Katriviernedersetting', 352 (my translation from the Dutch).

46 BPP 949 of 1849, 51.

47 Bowker and Groepe to Borcherds, 19 June 1848, CA 1/FBF 5/1/2/3/2, in reply to Borcherds to Bowker 8 June 1848, CA 1/FBF 6/1/3/1/1; for apparently comparable events, there described as 'upundhlo', see J.C. Warner, 'Notes' in John Maclean, Compendium of Kafir Laws and Customs, reprinted Frank Cass, 1966, 77, and Charles Brownlee in ibid, 129130. See also N. Erlank, 'Gender and Christianity among Africans attached to Scottish mission stations in Xhosaland in the nineteenth century' (Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge University, 1999), 66. I have no explanation for the use of the term 'Gieko', except that Brownlee wrote that 'the young men pleaded that they were only following "isiko",' or the custom, and 'Gieko' might be a mangling of 'isiko' made by two men, Borcherds and Groepe, neither of whom spoke Xhosa.

48 Montagu to Civil Commissioner, Fort Beaufort, 27 August 1849, CA LCB 9, also in CA 1/FBF 5/1/1/2/1. Cf. C.C. Crais, White Supremacy and Black Resistance in Pre-industrial South Africa: The Making of the Colonial Order in the Eastern Cape, 1770-1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 166.

49 On this, see T. Kirk, 'Self-Government and Self-defence in South Africa: The Inter-Relations between British and Cape Politics' (D.Phil, Oxford University, 1972).

50 It is for instance instructive to examine the poll lists from the Kat River in the 1854 elections for the Legislative Council, preserved in CO CA 2908. These show that the only men to give any (of their seven) votes to Godlonton were the Englishmen William Bates, Andrew Develing and Rienhaud Webb, plus Dirk Pieters, whose ethnicity I do not know and who, somewhat remarkably, split his vote between Godlonton and Stockenstrom.

51 Bowker to Weinand, 20 December 1848, CA CO 2849. Needless to say, emphasis in original.

52 Calderwood to LMS, 20 March 1843, LMS archive (SOAS), South African Incoming letters, (hereafter LMS-SA), 19/1/ C; Bowker and Groepe to Borcherds, 19 June 1848, CA 1/FBF 5/1/2/3/2.

53 J. Freeman, A Tour in South Africa (London: John Snow, 1851), 163.

54 Bowker and Groepe to Borcherds, 19 June 1848, CA 1/FBF 5/1/2/3/2.

55 E.g. Calderwood to Le Sueur, for Secretary to Government, 21 September 1849, CA LCB 9.

56 Claim of Andries Pretorius, CA 1/UIT 14/37, 95-99.

57 Gonaqua, or 'Gonas', were among those who occupied the middle ground between Xhosa and Khoi, so that the British did not know how to deal with them.

58 Bowker and Groepe to Borcherds, 19 June 1848, CA 1/FBF 5/1/2/3/2.

59 Report of the Blinkwater Commission, 93-94.

60 Bowker and Groepe to Borcherds, 19 June 1848, CA 1/FBF 5/1/2/3/2; Napier, Excursions, vol. 2, 372.

61 Montagu to Civil Commissioner, Fort Beaufort, 11 December 1848, CA LCB 9

62 Stringfellow to the Secretary to the Lieutenant Governor, 1 May 1855, LCB 9.

63 Calderwood to Le Sueur, for Secretary to Government, 21 September 1849, CA LCB 9.

64 Borcherds to Hudson, 11 July 1843, CA 1/AY 8/93.

65 Bowker to Colonial Secretary, 20.6.1848, CA CO 2849; this may have been the beginning of the removal of authority from Botha which characterised the period. It was particularly aggressive, and can, I think, only be explained as a reaction by the official class of the Eastern Cape to their collective shame at the fact that it was Botha's counter attack during the Battle of Burn's Hill at the start of the War of the Axe which effectively saved the colonial ammunition wagons, and thus prevented a greater disaster.

66 Borcherds, 'Instructions for the Superintendent of Fingoes and other natives at Fuller's Hoek, Hermanus Kloof Umvezo etc.', 20 February 1849, CA LCB 9.

67 This was hinted at by Stockenstrom in Light and Shade, 22.

68 See e.g. Stockenström to Montagu, 11 July 1850, printed in Trial of Andries Botha (Cape Town, Saul Solomon, 1852; reprinted Pretoria: State Library, 1969), 237-9; in this letter, Sir Andries was recording the complaints made to him by Andries Botha; Freeman, Tour in South Africa, 186-193.

69 Montagu to the 'Inhabitants of Blinkwater and Fuller's Hoek', 16 May 1849, 17 June 1849, CA LCB 9; this is in reply to a memorial of 16 May 1849, which I have been unable to locate as yet.

70 Read, Read and Thomson to Montagu, 22 August 1850, CA CO 592; Read et al to Stringfellow, 23 September 1850, CA CO 2863; Stringfellow to Montagu, 25 September 1850 CA CO 2863; Bowker to Montagu, 5 July 1850, CA CO 2870.

71 Brownlee to Mackinnon, 6 May 1850, printed in Freeman, Tour in South Africa, 180-1.

72 Reports of this expedition exist from both the Commander of the Police, (Davies to Mackinnon, 20 June 1850, printed in Freeman, Tour, 176-9), from the Civil Commissioner of Fort Beaufort, (Stringfellow to Secretary to Government, 22 June 1850) and the Resident Magistrate of Stockenstrom (Bowker to Stringfellow, 20 June 1850, Bowker to Secretary to Government, 27 June 1850), all of which are in CA LCB 9. The testimony of Andries Botha, who was one of those who suffered from the actions, is to be found in Botha to Smith, 23 June 1850, in Freeman, Tour, 182-3, and in Stockenstrom to Secretary to Government 11 July 1850, in Trial of Andries Botha, 236-9.

73 K.I. Watson, 'African Sepoys? The Black Police on the Eastern Cape frontier, 1836-1850', Kleio, vol. 28, 1996, 62-78.

74 Davies of the Police said that Hermanus's people were 'reported to be one hundred and thirty in number, but I am of opinion from my subsequent operations, that they are more than two hundred.'

75 Stockenstrom to Secretary to Government 11 July 1850, in Trial of Andries Botha, 237.

76 In general, see G. Harinck, 'Interaction between Xhosa and Khoi: emphasis on the period 1620-1750' in L.Thompson, ed., African Societies in Southern Africa (London: Heinemann, 1969); R. Ross, 'Ethnic identity, demographic crises and Xhosa-Khoikhoi interaction', History in Africa, vol. 7, 1980; more specifically, R. Ross, 'Ambiguities of resistance and collaboration on the Eastern Cape Frontier: The Kat River Settlement, 1829-1856' in J. Abbink, M. de Bruijn and K. van Walraven, eds., Rethinking Resistance: Revolt and Violence in African History (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2003), 129-132.

77 Bowker to Secretary to Government, 27 June 1850, CA LCB 9.

78 Bowker to Stringfellow, 20 June 1850, CA LCB 9.

79 On this visit, and for the citations, see 'Report of the Blinkwater Commission.'

80 J. Peires, The Dead will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle Killing Movement of 1856-7, (Johannesburg: Ravan, 1989), 1-12; Crais, White Supremacy, 175-6.

81 Read, Kat River Settlement in 1851, 18-19; Read snr to Freeman, 13 April 1851, LMS-SA 26/1/C.

82 One of Godlonton's correspondents claimed on 23 November 1850 that in the previous days Hermanus had visited Mlanjeni and had concerted plans while there with Sarhili and Sandile. In the tense situation of the border at that time, this rumour should not be accepted without further evidence (which I do not believe exists), but is nevertheless by no means implausible. See Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 29.

83 Crais, White supremacy, 177.

84 Evidence of the Rev. H. Renton, BPP 635 of 1851, 419; the British commanders had been warned of Hermanus's obedience to Mlanjeni's commands before they handed out the arms. McKay, Reminiscences, 61, claims that the commander of Fort Beaufort, Colonel W. Sutton, refused to issue the arms.

85 Read, Kat River Settlement in 1851, xvii.

86 See the statements in CA CO 4495A.

87 Isaacs's testimony during Trial of Andries Botha, 113; Major-General Henry Somerset (he had just been promoted), notice 8 Jan. 1851, in BPP 1334 of 1851, 127.

88 Watson, 'African sepoys?'.

89 Wienand to Somerset. 3 Jan. 1851, CA CO 4495A.

90 Read, Kat River Settlement in 1851, 12, 20; John Green, The Kat River Settlement in 1851 (Graham's Town: Godlonton and White, 1853), 39.

91 He was presumably the son of John Corner, a former LMS missionary (and ex-slave from Guyana) and his Khoi wife.

92 Read, Kat River Settlement in 1851, 13; James Read Jnr, 'Extracts from a notebook', LMS-SA 28/4/C, 11; Elizabeth Elbourne, Blood Ground: Colonialism, Missions and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 17991853 (Montreal, Kingston, London and Ithaca: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2002), 368, relates that she had been told that this betrayal, if it is to be seen as such, on the part of Read was what Xhosa most remember about him.

93 McKay, Reminiscences, 62.

94 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 136-7. Godlonton's anonymous correspondent had been on guard the night before, and may therefore have had to conceal that he had left his post before he should have done.

95 Mckay, Reminiscences, 62-3; Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 135-140.

96 Henry Somerset, Notice, 8 January 1851, BPP 1334 of 1851; McKay, Reminiscences, 62-3; Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 135-140.

97 Godlonton and Irving, Narrative, 138.

98 McKay, Reminiscences, 63.

99 There are families of amaJwara Xhosa, presumably his descendants, whose surname is Ngxukumeshe. Information from Michael Besten.